Monograph Series Chhimbe, Part-VB(Iv)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

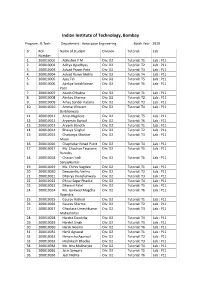

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Sindh Police Shaheed List

List of Shuhada of Sindh Police since 1942 to 2014 Date of Ser # Rank No. NAME Father Name Surname DSTT: Shahadat 1 IP K/1296 Ghazanfar Kazmi Syed Sarwar Ali Syed Kazmi South, Karachi 13.08.2014 2 PC 11049 Muhammad Siddiq Zer Muhammad Court Police 18.12.2013 3 PC 188 PC/188 Muhammad Khalid Muhammad Siddique Arain SBA, District 07.06.2014 4 HC 20296 HC/20296 Zulfqar Ali Unar s/o M Sachal Muhammad Sachal Unar Crime Br. Sukkur 29.07.2014 5 HC 17989 HC/17989 Haji Wakeel Ali Khair Muhammad West Karachi 17.08.2014 6 HC 13848 HC/ 13848 Tahir Mehmood Muhammad Aslam SRP-1, Karachi 19.08.2014 7 HC 19323 HC/19323 Azhar Abbas Muhammad Shafi Malir, Karachi 19.08.2014 8 PC 19386 PC/19386 Muhammad Azam Mir Muhammad Malir, Karachi 19.08.2014 9 PC 24318 PC/24318 Junaid Akbar Javed Akbar West Karachi 27.08.2014 10 PC 18442 PC/18442 Lutufullah Charann Muhammad Waris Charann Malir, Karachi 29.08.2014 11 ASI ASI Jamil Ahmed Babar Haji Ali Nawaz Babar Jamshoro 03.09.2014 12 HC 9636 HC/9636 Yousuf Khan Khushhal Khan Security-II 04.09.2014 13 SI K-5431 SI (K-5431) Ghulam Sarwar Gulsher Ali Central, Karachi 16.09.2014 14 PC 14491 PC/14491 Aijaz Ahmed Niaz Ahmed Central, Karachi 16.09.2014 15 HC 41 HC/41 Bashir Qureshi Allah Rakhio Qureshi Jamshoro 19.09.2014 16 PC 247 PC/247 Ameer Ali Junejo Roshan Ali Junejo Larkana 22.09.2014 17 PC 16150 PC/16150 Muhammad Tahir Farooq Muhammad Alam Central, Karachi 23.09.2014 18 DPC 18908 DPC/18908 Waqar Hashmi Shafiq Hashmi Hashmi Muhafiz Force, Karachi 16.10.2014 19 ASI K-2272 ASI/ K-2272 Qalandar Bux Malhan Khan Chandio -

Application No First Name Last Name Dob Domici Le Dis Trict Name Caste Gender Hse Pe Rcenta Ge Online Ass Sc Ore Hse 50 Weigh

DOMICI ONLINE_ HSE_PE ONLINE_ HSE_50_ LE_DIS ASS_50_ MERIT_ APPLICATION_NO FIRST_NAME LAST_NAME DOB CASTE GENDER RCENTA ASS_SC WEIGHTA TRICT_ WEIGHTA MARKS GE ORE GE NAME GE 030112018300 JAVED KHAN 13/08/1987 Bhopal OBC M 85.56 75 42.78 37.5 80.28 030112005050 ALKA GUPTA 31/05/1990 Bhopal UR F 79.78 70 39.89 35 74.89 030112049019 UPADHYAY SEEMA 12/04/1989 Bhopal UR F 80.67 68 40.34 34 74.34 030112075099 RITESH SHRIVASTAVA 31/10/1983 Bhopal UR M 76.44 72 38.22 36 74.22 030112080269 RACHANA SINGH 29/12/1985 Bhopal UR F 81.78 65 40.89 32.5 73.39 030112088665 NITIN YADAV 23/07/1990 Bhopal UR M 79.11 67 39.56 33.5 73.06 030112005757 SURENDRA SINGH DANGI 04/08/1979 Bhopal OBC M 60.67 85 30.34 42.5 72.84 030112016415 SHAILENDRA SINGH 10/12/1974 Bhopal OBC M 74.13 71 37.07 35.5 72.57 030112067261 PRADEEP CHOUHAN 08/05/1989 Bhopal OBC M 88 56 44 28 72 030112057789 AVINASH TIWARI 06/05/1989 Bhopal UR M 74.67 69 37.34 34.5 71.84 030112068616 HITESH MANVANI 03/06/1987 Bhopal UR M 78.22 65 39.11 32.5 71.61 030112072663 SACHIN JAIN 16/12/1986 Bhopal UR M 79.11 64 39.56 32 71.56 030112117333 AMAR SHUKLA 01/01/1989 Bhopal UR M 81.33 61 40.67 30.5 71.17 030112092140 PRITESH SINGH RAJPUT 10/09/1990 Bhopal UR M 79.33 63 39.67 31.5 71.17 030112043920 DEEPESHWAR PAWAR 19/11/1991 Bhopal UR M 80 62 40 31 71 030112056725 ANAS KHAN 03/08/1985 Bhopal UR M 75.78 66 37.89 33 70.89 030112105607 MADHU BALA SHARMA 14/02/1987 Bhopal UR F 85.56 56 42.78 28 70.78 030112058068 TANMAY JAIN 17/10/1988 Bhopal UR M 72.44 68 36.22 34 70.22 030112057398 PANKAJ PRAJAPATI 20/12/1991 -

The Merchant Castes of a Small Town in Rajasthan

THE MERCHANT CASTES OF A SMALL TOWN IN RAJASTHAN (a study of business organisation and ideology) CHRISTINE MARGARET COTTAM A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. at the Department of Anthropology and Soci ology, School of Oriental and African Studies, London University. ProQuest Number: 10672862 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672862 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Certain recent studies of South Asian entrepreneurial acti vity have suggested that customary social and cultural const raints have prevented positive response to economic develop ment programmes. Constraints including the conservative mentality of the traditional merchant castes, over-attention to custom, ritual and status and the prevalence of the joint family in management structures have been regarded as the main inhibitors of rational economic behaviour, leading to the conclusion that externally-directed development pro grammes cannot be successful without changes in ideology and behaviour. A focus upon the indigenous concepts of the traditional merchant castes of a market town in Rajasthan and their role in organising business behaviour, suggests that the social and cultural factors inhibiting positivejto a presen ted economic opportunity, stimulated in part by external, public sector agencies, are conversely responsible for the dynamism of private enterprise which attracted the attention of the concerned authorities. -

OFFICE of the CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER REASI List of Schools with Contact No. and Email.Id Name of the Head of the S

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF EDUCATION OFFICER REASI List of Schools with Contact no. and email.id Name of the Head of the S. No. Name of the School Zone Address Pin Code Phone No. Email Remarks (if any) School 1 GMS ARNAS ARNAS GMS ARNAS ZONE ARNAS 182313 BANSI LAL 9419295443 [email protected] 2 MS ARNAS ARNAS MIDDLE SCHOOL ARNAS ZONE ARNAS 182313 KEWAL KRISHAN NANDA 9622216440 [email protected] 3 B C A ARNAS (MS) ARNAS BCA ARNAS DIUSTT REASI 182313 JIA LAL 9622388513 [email protected] 4 G S N ARNAS (PS) ARNAS GSN ARNAS ZONE ARNAS 182313 NEETA DEVI 6006603836 [email protected] 5 HSS ARNAS ARNAS Govt., Higher Secondary Arnas Zone ArnasPost 182313 GAJAN SINGH 9419317568 [email protected] Office Arnas 6 KGBV ARNAS ARNAS KGBV ARNAS ZONE ARNAS 182313 SHANAZ ALHTER 8492983350 [email protected] 7 PS SIRAL ARNAS R/O KANTHAN TEHSIL ARNAS 182313 MANISHA SATWAL 9797681679 [email protected] 8 PS TADOO ARNAS R/o Arnas teh. Arnas Distt. Reasi 182313 SURJU DEVI 9797386687 [email protected] 9 INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION ARNAS R/O ARNAS TEH. ARNAS DISTT. REASI 182313 Ravinder Singh 9149685023 [email protected] ARNAS 10 MS BHARNALI ARNAS GOVT,M/S BHARNALI ZONE ARNAS DISTT.REASI 182313 ABDUL KARIM 9906062903 [email protected]. 11 HS CHILLAD ARNAS R/o Chilled Govt High School Chilled Zone Arnas 182313 ABDUL GANI MIR 9906228380 [email protected] 12 HS BARLA ARNAS VILLAGE CHILLAD TEH. THUROO. DISTT. REASI 182313 GHULAM MOHD 8803622506 [email protected] 13 MS BALOSMA ARNAS VILLAGE CHILLAD TEH. ARNAS DISTT. -

APPENDIX G. Bibliography of ECOTOX Open Literature

APPENDIX G. Bibliography of ECOTOX Open Literature Explanation of OPP Acceptability Criteria and Rejection Codes for ECOTOX Data Studies located and coded into ECOTOX must meet acceptability criteria, as established in the Interim Guidance of the Evaluation Criteria for Ecological Toxicity Data in the Open Literature, Phase I and II, Office of Pesticide Programs, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, July 16, 2004. Studies that do not meet these criteria are designated in the bibliography as “Accepted for ECOTOX but not OPP.” The intent of the acceptability criteria is to ensure data quality and verifiability. The criteria parallel criteria used in evaluating registrant-submitted studies. Specific criteria are listed below, along with the corresponding rejection code. · The paper does not report toxicology information for a chemical of concern to OPP; (Rejection Code: NO COC) • The article is not published in English language; (Rejection Code: NO FOREIGN) • The study is not presented as a full article. Abstracts will not be considered; (Rejection Code: NO ABSTRACT) • The paper is not publicly available document; (Rejection Code: NO NOT PUBLIC (typically not used, as any paper acquired from the ECOTOX holding or through the literature search is considered public) • The paper is not the primary source of the data; (Rejection Code: NO REVIEW) • The paper does not report that treatment(s) were compared to an acceptable control; (Rejection Code: NO CONTROL) • The paper does not report an explicit duration of exposure; (Rejection Code: NO DURATION) • The paper does not report a concurrent environmental chemical concentration/dose or application rate; (Rejection Code: NO CONC) • The paper does not report the location of the study (e.g., laboratory vs. -

List of Dehs in Sindh

List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 1 Badin Badin 1 Abri 2 Badin Badin 2 Achh 3 Badin Badin 3 Achhro 4 Badin Badin 4 Akro 5 Badin Badin 5 Aminariro 6 Badin Badin 6 Andhalo 7 Badin Badin 7 Angri 8 Badin Badin 8 Babralo-under sea 9 Badin Badin 9 Badin 10 Badin Badin 10 Baghar 11 Badin Badin 11 Bagreji 12 Badin Badin 12 Bakho Khudi 13 Badin Badin 13 Bandho 14 Badin Badin 14 Bano 15 Badin Badin 15 Behdmi 16 Badin Badin 16 Bhambhki 17 Badin Badin 17 Bhaneri 18 Badin Badin 18 Bidhadi 19 Badin Badin 19 Bijoriro 20 Badin Badin 20 Bokhi 21 Badin Badin 21 Booharki 22 Badin Badin 22 Borandi 23 Badin Badin 23 Buxa 24 Badin Badin 24 Chandhadi 25 Badin Badin 25 Chanesri 26 Badin Badin 26 Charo 27 Badin Badin 27 Cheerandi 28 Badin Badin 28 Chhel 29 Badin Badin 29 Chobandi 30 Badin Badin 30 Chorhadi 31 Badin Badin 31 Chorhalo 32 Badin Badin 32 Daleji 33 Badin Badin 33 Dandhi 34 Badin Badin 34 Daphri 35 Badin Badin 35 Dasti 36 Badin Badin 36 Dhandh 37 Badin Badin 37 Dharan 38 Badin Badin 38 Dheenghar 39 Badin Badin 39 Doonghadi 40 Badin Badin 40 Gabarlo 41 Badin Badin 41 Gad 42 Badin Badin 42 Gagro 43 Badin Badin 43 Ghurbi Page 1 of 142 List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 44 Badin Badin 44 Githo 45 Badin Badin 45 Gujjo 46 Badin Badin 46 Gurho 47 Badin Badin 47 Jakhralo 48 Badin Badin 48 Jakhri 49 Badin Badin 49 janath 50 Badin Badin 50 Janjhli 51 Badin Badin 51 Janki 52 Badin Badin 52 Jhagri 53 Badin Badin 53 Jhalar 54 Badin Badin 54 Jhol khasi 55 Badin Badin 55 Jhurkandi 56 Badin Badin 56 Kadhan 57 Badin Badin 57 Kadi kazia -

Cultural Geography of the Jats of the Upper Doab, India. Anath Bandhu Mukerji Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1960 Cultural Geography of the Jats of the Upper Doab, India. Anath Bandhu Mukerji Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mukerji, Anath Bandhu, "Cultural Geography of the Jats of the Upper Doab, India." (1960). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 598. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CULTURAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE JATS OF THE UPPER DQAB, INDIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Anath Bandhu Muker ji B.A. Allahabad University, 1949 M.A. Allahabad University, 1951 June, I960 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Individual acknowledgement to many persons who have, di rectly or indirectly, helped the writer in India and in United States is not possible; although the writer sincerely desires to make it. The idea of a human geography of the Jats as proposed by the writer was strongly supported at the very beginning by Dr. G. R. Gayre, formerly Professor of Anthropo-Geography at the University of Saugor, M. P. , India. In the preparation of the preliminary syn opsis and initial thinking on the subject able guidance was constantly given by Dr. -

Prior Rights District CTY - Region & Prior Rights Date 1 CHARBAN, J.(JOEL) (XW) 6/24/1976 THUNDER BAY LKH WEST July 13, 1995 2 BELL, R

CTY Seniority # NAME CTY - Date for District Lists Work Location CTY - Prior Rights CTY - Prior rights district CTY - Region & Prior Rights Date 1 CHARBAN, J.(JOEL) (XW) 6/24/1976 THUNDER BAY LKH WEST July 13, 1995 2 BELL, R. S.(RICHARD) (XE) 3/7/1978 MEDICINE HAT AB WEST July 13, 1995 3 HUNT, L.R. (LORNE) ESB 8/25/1978 LETHBRIDGE AB WEST July 13, 1995 4 DOHERTY,J.(JOHN) 7/14/1980 CALGARY AB WEST July 13, 1995 5 RICHARD, K.P.(KEVIN) 11/17/1980 COQUITLAM BC WEST July 13, 1995 6 LINKLETTER, M.J. (MIKE) 1/12/1981 CALGARY AB WEST July 13, 1995 7 CLERMONT, G. (GARTH) 4/6/1981 CALGARY AB WEST July 13, 1995 8 DOHERTY, T.A. (TOM) ESB 4/20/1981 RED DEER AB WEST July 13, 1995 9 LIND, W.E. (BILL) 12/14/1981 FORT STEELE BC WEST July 13, 1995 10 AULD, M.W. (MURRAY) ESB 3/15/1982 THUNDER BAY LKH WEST July 13, 1995 11 HIGH, K.P. (KEVIN) NO ONLY 9/23/1983 CALGARY AB WEST July 13, 1995 12 O'REILLY, C.T.(TRENT) ESB 9/23/1983 MEDICINE HAT AB WEST July 13, 1995 13 EDEL, WE (WYNN) ESB 1/20/1984 WINNIPEG MB WEST July 13, 1995 14 DUTKIEWICH,K(KEITH) ESB 1/20/1984 WINNIPEG MB WEST July 13, 1995 15 REID, J.M. (JEFF) ESB 1/21/1984 BRANDON MB WEST July 13, 1995 16 JARDINE, K.M. (KEVIN) 3/2/1984 CALGARY AB WEST July 13, 1995 17 WAYNE, G.A. -

Annual Return – MGT-7

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of rule 11of the Companies (Management and Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company L14102TG1991PLC013299 Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company AABCP2100Q (ii) (a) Name of the company POKARNA LIMITED (b) Registered office address 1ST FLOOR, 105,SURYA TOWERS, SECUNDERABAD. A.P Telangana 500003 India (c) *e-mail ID of the company [email protected] (d) *Telephone number with STD code 04027897722 (e) Website www.pokarna.com (iii) Date of Incorporation 09/10/1991 (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company Public Company Company limited by shares Indian Non-Government company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 15 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 B.S.E Limited 1 2 National Stock Exchange of India 1,024 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent U72400TG2017PTC117649 Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent KFIN TECHNOLOGIES PRIVATE LIMITED Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents Selenium, Tower B, Plot No- 31 & 32, Financial District, Nanakramguda, Serilingampally (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM (b) Due date of AGM 30/09/2021 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No (f) Specify the reasons for not holding the same II. -

Appendix H. Accepted ECOTOX Data Table (Sorted by Effect) and Bibliography

Appendix H. Accepted ECOTOX Data Table (sorted by effect) and Bibliography Table H-1. Freshwater fish data from ECOTOX. Data are arranged in alphabetical order by Effect Group. The code list for ECOTOX can be found at: http://cfpub.epa.gov/ecotox/blackbox/help/codelist.pdf. Chemical Effect Conc Conc Conc % Species Effect Meas Endpt1 Endpt2 Dur Dur Unit Ref # Name Group Value1 Value2 Units Purity Hyphessobrycon bifasciatus, Endosulfan II ACC ACC GACC BCF 21 d 0.0001 mg/L 100 7009 Yellow tetra Hyphessobrycon bifasciatus, Endosulfan ACC ACC GACC BCF 21 d 0.0003 mg/L 100 7009 Yellow tetra Hyphessobrycon bifasciatus, Endosulfan I ACC ACC GACC BCF 21 d 0.0002 mg/L 100 7009 Yellow tetra Hyphessobrycon bifasciatus, Endosulfan ACC ACC GACC BCF 21 d 0.0002 mg/L 100 8035 Yellow tetra Hyphessobrycon bifasciatus, Endosulfan ACC ACC GACC BCF 21 d 0.0003 mg/L 100 8035 Yellow tetra Hyphessobrycon bifasciatus, Endosulfan ACC ACC GACC BCF 21 d 0.0001 mg/L 100 8035 Yellow tetra Endosulfan I Salmo salar, Atlantic salmon ACC ACC GACC BAF 92 d 0.724 ppm 100 104113 Endosulfan II Salmo salar, Atlantic salmon ACC ACC GACC BAF 92 d 0.315 ppm 100 104113 Endosulfan I Salmo salar, Atlantic salmon ACC ACC RSDE NOAEL 49 d 0.03 ppm 99.8 104340 Channa punctata, Snake-head Endosulfan BCM ENZ GSTR LOEC 1 d 0.005 mg/L 100 81028 catfish Channa punctata, Snake-head Endosulfan BCM BCM PCAR LOEC 1 d 0.005 mg/L 100 81028 catfish Channa punctata, Snake-head Endosulfan BCM ENZ GSTR LOEC 1 d 0.005 mg/L 100 81028 catfish Channa punctata, Snake-head Endosulfan BCM ENZ CTLS LOEC 1 d 0.005 mg/L 100 81028 catfish Channa punctata, Snake-head Endosulfan BCM BCM GLTH LOEC 1 d 0.005 mg/L 100 81028 catfish Channa punctata, Snake-head Endosulfan BCM ENZ GLRE LOEC 1 d 0.005 mg/L 100 81028 catfish Page H-1 Table H-1. -

Birds in Our Lives

BIRDS IN OUR LIVES Related titles from Universities Press Amphibians of Peninsular India RJ Ranjith Daniels Birds: Beyond Watching Abdul Jamil Urfi Butterflies of Peninsular India Krushnamegh Kunte Freshwater Fishes of Peninsular India RJ Ranjith Daniels Marine Mammals of India Kumaran Sathasivam Marine Turtles of the Indian Subcontinent Kartik Shanker and BC Choudhury (eds) Eye in the Jungle: M Krishnan: Photographs and Writings Ashish and Shanthi Chandola and TNA Perumal (eds) Field Days AJT Johnsingh The Way of the Tiger K Ullas Karanth Forthcoming titles Mammals of South Asia, Vols 1 and 2 AJT Johnsingh and Nima Manjrekar (eds) Spiders of India PA Sebastian and KV Peter BIRDS IN OUR LIVES A SHISH K OTHARI Illustrations by Madhuvanti Anantharajan Universities Press UNIVERSITIES PRESS (INDIA) PRIVATE LIMITED Registered Office 3-6-747/1/A and 3-6-754/1 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A P), India Email: [email protected] Distributed by Orient Longman Private Limited Registered Office 3-6-752, Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A P), India Other Offices Bangalore, Bhopal, Bhubaneswar, Chennai, Ernakulam, Guwahati, Hyderabad, Jaipur, Kolkata, Lucknow, Mumbai, New Delhi, Patna © Ashish Kothari 2007 Cover and book design © Universities Press (India) Private Limited 2007 ISBN 13: 978 81 7371 586 0 ISBN 10: 81 7371 586 6 Set in Aldine 721 BT 10 on 13 by OSDATA Hyderabad 500 029 Printed in India at Graphica Printers Hyderabad 500 013 Published by Universities Press (India) Private Limited 3-6-747/1/A and 3-6-754/1 Himayatnagar, Hyderabad 500 029 (A P), India V V V V V X X Contents Preface and Acknowledgements XII 1.