Copyright by Kenneth Leland Price 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping India's Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and Its

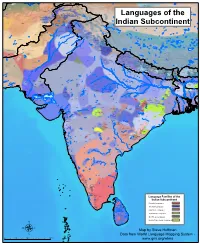

Mapping India’s Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and its Exclusion in the Indian Census Dr. Shivakumar Jolad1 and Aayush Agarwal2 1FLAME University, Lavale, Pune, India 2Centre for Social and Behavioural Change, Ashoka University, New Delhi, India Abstract In this article, we critique the process of linguistic data enumeration and classification by the Census of India. We map out inclusion and exclusion under Scheduled and non-Scheduled languages and their mother tongues and their representation in state bureaucracies, the judiciary, and education. We highlight that Census classification leads to delegitimization of ‘mother tongues’ that deserve the status of language and official recognition by the state. We argue that the blanket exclusion of languages and mother tongues based on numerical thresholds disregards the languages of about 18.7 million speakers in India. We compute and map the Linguistic Diversity Index of India at the national and state levels and show that the exclusion of mother tongues undermines the linguistic diversity of states. We show that the Hindi belt shows the maximum divergence in Language and Mother Tongue Diversity. We stress the need for India to officially acknowledge the linguistic diversity of states and make the Census classification and enumeration to reflect the true Linguistic diversity. Introduction India and the Indian subcontinent have long been known for their rich diversity in languages and cultures which had baffled travelers, invaders, and colonizers. Amir Khusru, Sufi poet and scholar of the 13th century, wrote about the diversity of languages in Northern India from Sindhi, Punjabi, and Gujarati to Telugu and Bengali (Grierson, 1903-27, vol. -

Environmental Studies for Undergraduate Courses

Environmental Studies For Undergraduate Courses Erach Bharucha CORE MODULE SYLLABUS FOR ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES FOR UNDER GRADUATE COURSES OF ALL BRANCHES OF HIGHER EDUCATION Vision The importance of environmental science and environmental studies cannot be disputed. The need for sustainable development is a key to the future of mankind. Continuing problems of pollution, loss of forget, solid waste disposal, degradation of environment, issues like economic productivity and national security, Global warming, the depletion of ozone layer and loss of biodiversity have made everyone aware of environmental issues. The United Nations Coference on Environment and Development held in Rio de Janerio in 1992 and world Summit on Sustainable Development at Johannesburg in 2002 have drawn the attention of people around the globe to the deteriorating condition of our environment. It is clear that no citizen of the earth can afford to be ignorant of environment issues. Environmental management has captured the attention of health care managers. Managing environmental hazards has become very important. Human beings have been interested in ecology since the beginning of civilization. Even our ancient scriptures have emphasized about practices and values of environmental conservation. It is now even more critical than ever before for mankind as a whole to have a clear understanding of environmental concerns and to follow sustainable development practices. India is rich in biodiversity which provides various resources for people. It is also basis for biotechnology. Only about 1.7 million living organisms have been diescribed and named globally. Still manay more remain to be identified and described. Attempts are made to I conserve them in ex-situ and in-situ situations. -

Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India

Chapter one: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India 1.1 Introduction: India also known as Bharat is the seventh largest country covering a land area of 32, 87,263 sq.km. It stretches 3,214 km. from North to South between the extreme latitudes and 2,933 km from East to West between the extreme longitudes. On this 2.4 % of earth‟s surface, lives 16% of world‟s population. With a population of 1,028,737,436 variations is there at every step of life. India is a land of bewildering diversity. India is bounded by the Indian Ocean on the Figure 1.1: India in World Population south, the Arabian Sea on the west and the Bay of Bengal on the east. Many outsiders explored India via these routes. The whole of India is divided into twenty eight states and seven union territories. Each state has its own cultural and linguistic peculiarities and diversities. This diversity can be seen in every aspect of Indian life. Whether it is culture, language, script, religion, food, clothing etc. makes ones identity multi-dimensional. Ones identity lies in his language, his culture, caste, state, village etc. So one can say India is a multi-centered nation. Indian multilingualism is unique in itself. It has been rightly said, “Each part of India is a kind of replica of the bigger cultural space called India.” (Singh U. N, 2009). Also multilingualism in India is not considered a barrier but a boon. 17 Chapter One: Social, Cultural and Linguistic Landscape of India Languages act as bridges because it enables us to know about others. -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 A’ou [aou] Iouo China 2 Abai Sungai [abf] Iouo Malaysia 3 Abaza [abq] Iouo Russia, Turkey 4 Abinomn [bsa] Iouo Indonesia 5 Abkhaz [abk] Iouo Georgia, Turkey 6 Abui [abz] Iouo Indonesia 7 Abun [kgr] Iouo Indonesia 8 Aceh [ace] Iouo Indonesia 9 Achang [acn] Iouo China, Myanmar 10 Ache [yif] Iouo China 11 Adabe [adb] Iouo East Timor 12 Adang [adn] Iouo Indonesia 13 Adasen [tiu] Iouo Philippines 14 Adi [adi] Iouo India 15 Adi, Galo [adl] Iouo India 16 Adonara [adr] Iouo Indonesia Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Russia, Syria, 17 Adyghe [ady] Iouo Turkey 18 Aer [aeq] Iouo Pakistan 19 Agariya [agi] Iouo India 20 Aghu [ahh] Iouo Indonesia 21 Aghul [agx] Iouo Russia 22 Agta, Alabat Island [dul] Iouo Philippines 23 Agta, Casiguran Dumagat [dgc] Iouo Philippines 24 Agta, Central Cagayan [agt] Iouo Philippines 25 Agta, Dupaninan [duo] Iouo Philippines 26 Agta, Isarog [agk] Iouo Philippines 27 Agta, Mt. Iraya [atl] Iouo Philippines 28 Agta, Mt. Iriga [agz] Iouo Philippines 29 Agta, Pahanan [apf] Iouo Philippines 30 Agta, Umiray Dumaget [due] Iouo Philippines 31 Agutaynen [agn] Iouo Philippines 32 Aheu [thm] Iouo Laos, Thailand 33 Ahirani [ahr] Iouo India 34 Ahom [aho] Iouo India 35 Ai-Cham [aih] Iouo China 36 Aimaq [aiq] Iouo Afghanistan, Iran 37 Aimol [aim] Iouo India 38 Ainu [aib] Iouo China 39 Ainu [ain] Iouo Japan 40 Airoran [air] Iouo Indonesia 1 Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 41 Aiton [aio] Iouo India 42 Akeu [aeu] Iouo China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, -

ONLINE APPENDIX: Not for Print Publication

ONLINE APPENDIX: not for print publication A Additional Tables and Figures Figure A1: Permutation Tests Panel A: Female Labor Force Participation Panel B: Gender Difference in Labor Force Participation A1 Table A1: Cross-Country Regressions of LFP Ratio Dependent variable: LFPratio Specification: OLS OLS OLS (1) (2) (3) Proportion speaking gender language -0.16 -0.25 -0.18 (0.03) (0.04) (0.04) [p < 0:001] [p < 0:001] [p < 0:001] Continent Fixed Effects No Yes Yes Country-Level Geography Controls No No Yes Observations 178 178 178 R2 0.13 0.37 0.44 Robust standard errors are clustered by the most widely spoken language in all specifications; they are reported in parentheses. P-values are reported in square brackets. LFPratio is the ratio of the percentage of women in the labor force, mea- sured in 2011, to the percentage of men in the labor force. Geography controls are the percentage of land area in the tropics or subtropics, average yearly precipitation, average temperature, an indicator for being landlocked, and the Alesina et al. (2013) measure of suitability for the plough. A2 Table A2: Cross-Country Regressions of LFP | Including \Bad" Controls Dependent variable: LFPf LFPf - LFPm Specification: OLS OLS (1) (2) Proportion speaking gender language -6.66 -10.42 (2.80) (2.84) [p < 0:001] [p < 0:001] Continent Fixed Effects Yes Yes Country-Level Geography Controls Yes Yes Observations 176 176 R2 0.57 0.68 Robust standard errors are clustered by the most widely spoken language in all specifications; they are reported in parentheses. -

137 Language Endangerment of Mewari: Study on the Changes In

Language Endangerment of Mewari; study on the changes in Speakers Attitude Language Endangerment of Mewari: Study on the Changes in Speakers Attitude Iman Sharma [email protected] Abstract Mewari is the language of Mewar region of Rajasthan. This region includes four districts, which are, Chittorgarh, Rajsamand, Bhilwara and Udaipur, and other than that, a few nearby parts of Madhya Pradesh. Among these, pure Mewari is spoken in Chittorgarh. Although the total population is as high as 17, 410, 568 (according to Census 2011), there is a rapid change in the attitude of its speakers, especially within the younger generation. One of the main reason observed is the dominance of Hindi, in terms of economic status, education qualification and home location (whether rural or urban). Moreover, Mewari does not have a script. As a result of which, although rich in folklores, these are nowhere documented. One reason for this is seen as unawareness of its speaker. According to a native speaker of Mewari, residing in Chittorgarh, the earlier edition of RBSE textbooks of EVS had a chapter on the Mewari language in Class 3, but the recent edition has removed this chapter. Thus, for the younger generation, they do not get to see any significant written work related to their language; as they see in other languages of their immediate environment, like Hindi and English. This paper studies the reason behind this change in attitude of the speakers, based on some observations and conversations with local people of Chittorgarh. Key words: Mewari, Language Attitude, Economic status. Introduction Mewari, the language spoken in the Mewar region of southeast Rajasthan, belongs to the Indo-Aryan family of language. -

Languages of India Being a Reprint of Chapter on Languages

THE LANGUAGES OF INDIA BEING A :aEPRINT OF THE CHAPTER ON LANGUAGES CONTRIBUTED BY GEORGE ABRAHAM GRIERSON, C.I.E., PH.D., D.LITT., IllS MAJESTY'S INDIAN CIVIL SERVICE, TO THE REPORT ON THE OENSUS OF INDIA, 1901, TOGETHER WITH THE CENSUS- STATISTIOS OF LANGUAGE. CALCUTTA: OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, INDIA. 1903. CALcuttA: GOVERNMENT OF INDIA. CENTRAL PRINTING OFFICE, ~JNGS STRERT. CONTENTS. ... -INTRODUCTION . • Present Knowledge • 1 ~ The Linguistio Survey 1 Number of Languages spoken ~. 1 Ethnology and Philology 2 Tribal dialects • • • 3 Identification and Nomenolature of Indian Languages • 3 General ammgemont of Chapter • 4 THE MALAYa-POLYNESIAN FAMILY. THE MALAY GROUP. Selung 4 NicobaresB 5 THE INDO-CHINESE FAMILY. Early investigations 5 Latest investigations 5 Principles of classification 5 Original home . 6 Mon-Khmers 6 Tibeto-Burmans 7 Two main branches 7 'fibeto-Himalayan Branch 7 Assam-Burmese Branch. Its probable lines of migration 7 Siamese-Chinese 7 Karen 7 Chinese 7 Tai • 7 Summary 8 General characteristics of the Indo-Chinese languages 8 Isolating languages 8 Agglutinating languages 9 Inflecting languages ~ Expression of abstract and concrete ideas 9 Tones 10 Order of words • 11 THE MON-KHME& SUB-FAMILY. In Further India 11 In A.ssam 11 In Burma 11 Connection with Munds, Nicobar, and !lalacca languages 12 Connection with Australia • 12 Palaung a Mon- Khmer dialect 12 Mon. 12 Palaung-Wa group 12 Khaasi 12 B2 ii CONTENTS THE TIllETO-BuRMAN SUll-FAMILY_ < PAG. Tibeto-Himalayan and Assam-Burmese branches 13 North Assam branch 13 ~. Mutual relationship of the three branches 13 Tibeto-H imalayan BTanch. -

'The Mewar Regalia: Textiles and Costumes', the City Palace

Documentation Project ‘The Mewar Regalia: Textiles and Costumes’, The City Palace Museum, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India: An Overview Smita Singh, Textile Conservation Consultant Abstract ‘The Mewar Regalia: Textiles and Costumes’ Royal collection comprising of more than 500 costumes, accessories and textile objects, belongs to Shriji Arvind Singh Mewar of Udaipur, 76th Custodian, House of Mewar and his royal ancestors. This collection is currently under the patronage of Maharana Mewar Charitable Foundation, (MMCF), The City Palace Museum, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India. This paper discusses the aspects and challenges associated with the Documentation Project of the collection mentioned above. The work comprised of planning strategy for textile documentation in a restricted time frame, establishment of documentation section, categorization of objects, preparation of inventory list and index cards, providing objects an accession number, labeling and marking, digital documentation vis-à- vis photographic documentation, compilation and subsequent utilization of literary and oral information regarding local terms for costumes along with diacritical marks and Indian terminology of pattern making etc. 1. Introduction 1.1 Location Udaipur is known for its history, culture, and picturesque locations and for its Palace Architecture. Udaipur, also called the city of lakes, is situated in the western Indian state of Rajasthan. It was founded by Maharana Udai Singh II in 1553 and was formerly the capital of kingdom of Mewar. Maharana Udai Singh Ji II and his successor Maharanas built the City Palace Complex concurrently with the establishment of the Udaipur city in 1559 and subsequently expanded it over a period of approximately 300 years. It is considered to be the largest Palace complex in Rajasthan and is replete with history. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System

Tajiki Tajiki Tajiki Pashto, Southern Shughni Tajiki Wakhi Wakhi Shughni Chinese, Mandarin Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Wakhi Sanglechi-Ishkashimi Wakhi Khowar Khowar Domaaki Khowar Kati Shina Farsi, Eastern Yidgha Munji Kati Kalasha Gujari Kati KatiPhalura Gujari Kalami Shina, Kohistani Gawar-BatiKamviri Kalami Dameli TorwaliKohistani, Indus Gujari Chilisso Pashayi, Northwest Prasuni Kamviri Balti Kati Ushojo Gowro Languages of the Gawar-Bati Waigali Savi Chilisso Ladakhi Ladakhi Bateri Pashayi, SouthwestAshkun Tregami Pashayi, Northeast Shina Purik Grangali Shina Brokskat ParyaPashayi, Southeast Aimaq Shumashti Hindko, Northern Hazaragi GujariKashmiri Pashto, Northern Purik Tirahi Ladakhi Changthang Kashmiri Gujari Indian Subcontinent Gujari Pahari-PotwariGujari Gujari Bhadrawahi Zangskari Hindko, Southern Ladakhi Pangwali Churahi Ormuri Pattani Gahri Ormuri Dogri-Kangri Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Pashto, Southern Ladakhi Pashto, Central Khams Pahari, Kullu Kinnauri, Bhoti KinnauriSunam Gahri Shumcho Panjabi, Western Mandeali Jangshung Tukpa Bilaspuri Kinnauri, Chitkuli Pahari, Mahasu Panjabi, Eastern Panang Jaunsari Garhwali Balochi, Western Pashto, Southern Khetrani Tehri Rawat Tibetan Hazaragi Waneci Rawat Brahui Saraiki DarmiyaByangsi Chaudangsi Tibetan Balochi, Western Chaudangsi Bagri Kumauni Humla Bhotia Rangkas Dehwari Mugu Kumauni Tichurong Dolpo Haryanvi Urdu Buksa Lopa Nepali Kaike Panchgaunle Balochi, Eastern Raute Tichurong Sholaga Baragaunle Raji Nar Phu Tharu, Rana Sonha Thakali Kham, GamaleKham, Sheshi -

LANGUAGES of INDIA WHITE PAPER Languages of India I

LANGUAGES OF INDIA WHITE PAPER Languages of India i About Andovar Andovar is a global provider of multilingual content solutions. Our services range from text translation and content creation, through audio and video recording, to turnkey localization of websites, software, eLearning and games. Our headquarters is in Singapore, and offices in Thailand, Colombia, USA and India. About This White Paper Andovar opened an office in Kolkata in 2014 to better serve our international clients and to add Indian language translation and audio recording to our suite of services. This white paper is an attempt to understand the localization situation when it comes to the major languages spoken in India. This has proven to be a challenging task. Not only are there dozens of languages and over ten scripts in everyday use in India, but it is also a rapidly developing country, with a huge and growing economy and new intiatives related to languages, encoding and translation technology support appear almost monthly. Not much has been written to date to give a holistic overview of the localization landscape and hopefully this white paper will be a useful reference to language professionals, even if it is far from perfect. As such, there may be mistakes or missing information which will be added in future updates. Please contact [email protected] with any questions or suggestions. The data on number or speakers and native speakers of Indian languages is unreliable, with different sources following different conventions when deciding what is a language and what is merely a dialect*. Our first source is the Indian Census from 2001 (www.censusindia.gov.in/Census_Data_2001/), which provided comprehensive information about the whole country, but is now outdated. -

Selfpublishing.Com 6X9 Template

Title Of Book Copyright Page Copyright © 2014 by Penn Bobby Singh (Pen Name) And RAJ International Inc. All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review. Printed in the United States of America First Printing, 2014-15 ISBN 0-0000000-0-0 Publisher: Star Publish LLC T.C. McMullen 563 Thomas Road Loretto, PA 15940 http://www.starpublishllc.com Ordering Information: Quantity sales. Special discounts are available on quantity purchases by corporations, associations, and others. For details, contact the publisher at the address above. Orders by U.S. bookstores and wholesalers. Please contact Star Publish LLC: Tel: (800) 800-8000; Fax: (800) 800-8001 or visit their website above 1 Author Of Book Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge and express my gratitude to, the following individuals: 1. Ralf Heynen for his photo of Patwon Ki Haveli in Jaisalmer which is used in the front book cover 2. Janet Elaine Smith, my editor for her support and kindness 3. Gary and Sandra Worthington for reviewing the book, providing very useful input and their support 4. Late Budh Singh Sb Bapna for providing oral history for this book, particularly the stories of Deoraj, Guman Chand and Zorawarmal 5. Late P. S. Bapna Sb for providing oral history , for this book , particularly stories of Chhogmal and Siremal 6. Late Ratan Kumari Bapna Sb, for providing oral history for this book, particularly stories of Zorawarmal and Chhogmal 7. -

WILDRE-2 2Nd Workshop on Indian Language Data

WILDRE2 - 2nd Workshop on Indian Language Data: Resources and Evaluation Workshop Programme 27th May 2014 14.00 – 15.15 hrs: Inaugural session 14.00 – 14.10 hrs – Welcome by Workshop Chairs 14.10 – 14.30 hrs – Inaugural Address by Mrs. Swarn Lata, Head, TDIL, Dept of IT, Govt of India 14.30 – 15.15 hrs – Keynote Lecture by Prof. Dr. Dafydd Gibbon, Universität Bielefeld, Germany 15.15 – 16.00 hrs – Paper Session I Chairperson: Zygmunt Vetulani Sobha Lalitha Devi, Vijay Sundar Ram and Pattabhi RK Rao, Anaphora Resolution System for Indian Languages Sobha Lalitha Devi, Sindhuja Gopalan and Lakshmi S, Automatic Identification of Discourse Relations in Indian Languages Srishti Singh and Esha Banerjee, Annotating Bhojpuri Corpus using BIS Scheme 16.00 – 16.30 hrs – Coffee break + Poster Session Chairperson: Kalika Bali Niladri Sekhar Dash, Developing Some Interactive Tools for Web-Based Access of the Digital Bengali Prose Text Corpus Krishna Maya Manger, Divergences in Machine Translation with reference to the Hindi and Nepali language pair András Kornai and Pushpak Bhattacharyya, Indian Subcontinent Language Vitalization Niladri Sekhar Dash, Generation of a Digital Dialect Corpus (DDC): Some Empirical Observations and Theoretical Postulations S Rajendran and Arulmozi Selvaraj, Augmenting Dravidian WordNet with Context Menaka Sankarlingam, Malarkodi C S and Sobha Lalitha Devi, A Deep Study on Causal Relations and its Automatic Identification in Tamil Panchanan Mohanty, Ramesh C. Malik & Bhimasena Bhol, Issues in the Creation of Synsets in Odia: A Report1 Uwe Quasthoff, Ritwik Mitra, Sunny Mitra, Thomas Eckart, Dirk Goldhahn, Pawan Goyal, Animesh Mukherjee, Large Web Corpora of High Quality for Indian Languages i Massimo Moneglia, Susan W.