Languages of India Being a Reprint of Chapter on Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

Numbers in Bengali Language

NUMBERS IN BENGALI LANGUAGE A dissertation submitted to Assam University, Silchar in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Masters of Arts in Department of Linguistics. Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGE ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR 788011, INDIA YEAR OF SUBMISSION : 2020 CONTENTS Title Page no. Certificate 1 Declaration by the candidate 2 Acknowledgement 3 Chapter 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1.0 A rapid sketch on Assam 4 1.2.0 Etymology of “Assam” 4 Geographical Location 4-5 State symbols 5 Bengali language and scripts 5-6 Religion 6-9 Culture 9 Festival 9 Food havits 10 Dresses and Ornaments 10-12 Music and Instruments 12-14 Chapter 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 15-16 Chapter 3: OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY Objectives 16 Methodology and Sources of Data 16 Chapter 4: NUMBERS 18-20 Chapter 5: CONCLUSION 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 22 CERTIFICATE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES ASSAM UNIVERSITY SILCHAR DATE: 15-05-2020 Certified that the dissertation/project entitled “Numbers in Bengali Language” submitted by Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No 03-120032252 of 2018-2019 for Master degree in Linguistics in Assam University, Silchar. It is further certified that the candidate has complied with all the formalities as per the requirements of Assam University . I recommend that the dissertation may be placed before examiners for consideration of award of the degree of this university. 5.10.2020 (Asst. Professor Paramita Purkait) Name & Signature of the Supervisor Department of Linguistics Assam University, Silchar 1 DECLARATION I hereby Roll - 011818 No - 2083100012 Registration No – 03-120032252 hereby declare that the subject matter of the dissertation entitled ‘Numbers in Bengali language’ is the record of the work done by me. -

Ethnicity, Education and Equality in Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 36 Number 2 Article 6 December 2016 New Languages of Schooling: Ethnicity, Education and Equality in Nepal Uma Pradhan University of Oxford, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Pradhan, Uma. 2016. New Languages of Schooling: Ethnicity, Education and Equality in Nepal. HIMALAYA 36(2). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol36/iss2/6 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Languages of Schooling: Ethnicity, Education, and Equality in Nepal Uma Pradhan Mother tongue education has remained this attempt to seek membership into a controversial issue in Nepal. Scholars, multiple groups and display of apparently activists, and policy-makers have favored contradictory dynamics. On the one hand, the mother tongue education from the standpoint practices in these schools display inward- of social justice. Against these views, others looking characteristics through the everyday have identified this effort as predominantly use of mother tongue, the construction of groupist in its orientation and not helpful unified ethnic identity, and cultural practices. in imagining a unified national community. On the other hand, outward-looking dynamics Taking this contention as a point of inquiry, of making claims in the universal spaces of this paper explores the contested space of national education and public places could mother tongue education to understand the also be seen. -

7=SINO-INDIAN Phylosector

7= SINO-INDIAN phylosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 525 7=SINO-INDIAN phylosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This phylosector comprises 22 sets of languages spoken by communities in eastern Asia, from the Himalayas to Manchuria (Heilongjiang), constituting the Sino-Tibetan (or Sino-Indian) continental affinity. See note on nomenclature below. 70= TIBETIC phylozone 71= HIMALAYIC phylozone 72= GARIC phylozone 73= KUKIC phylozone 74= MIRIC phylozone 75= KACHINIC phylozone 76= RUNGIC phylozone 77= IRRAWADDIC phylozone 78= KARENIC phylozone 79= SINITIC phylozone This continental affinity is composed of two major parts: the disparate Tibeto-Burman affinity (zones 70= to 77=), spoken by relatively small communities (with the exception of 77=) in the Himalayas and adjacent regions; and the closely related Chinese languages of the Sinitic set and net (zone 79=), spoken in eastern Asia. The Karen languages of zone 78=, formerly considered part of the Tibeto-Burman grouping, are probably best regarded as a third component of Sino-Tibetan affinity. Zone 79=Sinitic includes the outer-language with the largest number of primary voices in the world, representing the most populous network of contiguous speech-communities at the end of the 20th century ("Mainstream Chinese" or so- called 'Mandarin', standardised under the name of Putonghua). This phylosector is named 7=Sino-Indian (rather than Sino-Tibetan) to maintain the broad geographic nomenclature of all ten sectors of the linguasphere, composed of the names of continental or sub-continental entities. -

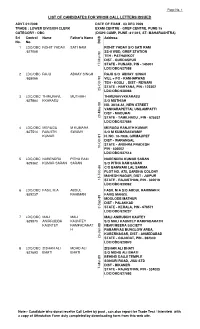

Ldc Final Merit

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED ADVT-01/2009 DATE OF EXAM - 03 DEC 2009 TRADE : LOWER DIVISION CLERK EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 CATEGORY - OBC (DIGHI CAMP, PUNE -411015, ST- MAHARASHTRA) Srl Control Name Father's Name Address No. No. DOB 1 LDC/OBC ROHIT YADAV SATI RAM ROHIT YADAV S/O SATI RAM /627088 SS-II WSD, GREF STATION TEH - PATHANKOT DIST - GURDASPUR STATE - PUNJAB, PIN - 145001 17-Mar-90 LDC/OBC/627088 2 LDC/OBC RAJU ABHAY SINGH RAJU S/O ABHAY SINGH /628066 VILL + PO - KANHARWAS TEH - KOSLI , DIST - REWARI STATE - HARYANA, PIN - 123302 25-Oct-90 LDC/OBC/628066 3 LDC/OBC THIRUNAVL MUTHIAH THIRUNAVVKKARASU /627884 KKARASU S/O MUTHIAH NO. 38/34 A1, NEW STREET VANNARAPETTAI, USILAMPATTI DIST - MADURAI 20-May-88 STATE - TAMILNADU , PIN - 625532 LDC/OBC/627884 4 LDC/OBC MERUGU M KUMARA MERUGU RANJITH KUMAR /627514 RANJITH SWAMY S/O M KUMARASWAMY KUMAR H. NO. 10-7936, GIRMAJIPET DIST - WARANGAL STATE - ANDHRA PRADESH 10-Oct-81 PIN - 506002 LDC/OBC/627514 5 LDC/OBC NARENDRA PITHA RAM NARENDRA KUMAR SARAN /629362 KUMAR SARAN SARAN S/O PITHA RAM SARAN C/O BANWARI LAL SARMA PLOT NO. A75, SARDHA COLONY MAHESH NAGAR, DIST - JAIPUR 15-Feb-86 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 302019 LDC/OBC/629362 6 LDC/OBC FASIL M.A ABDUL FASIL M A S/O ABDUL RAHIMAN K /629237 RAHIMAN FARIS MANZIL MOOLODE MATHUR DIST - PALAKKAD 2-Sep-89 STATE - KERALA, PIN - 678571 LDC/OBC/629237 7 LDC/OBC MALI MALI MALI ANIRUDDH KAUTEY /629870 ANIRRUDDH KAUNTEY S/O MALI KAUNTEY RAMPADARATH KAUNTEY RAMPADARAT NEAR MEERA SOCIETY H RABARIVAS BUNGLOW AREA, KUBERNAGAR, DIST - AHMEDABAD 23-Jan-88 STATE - GUJARAT, PIN - 382340 LDC/OBC/629870 8 LDC/OBC ZISHAN ALI MOHD ALI ZISHAN ALI BHATI /627693 BHATI BHATI S/O MOHD ALI BHATI BEHIND DAUJI TEMPLE SONGRI ROAD, JISU STD DIST - BIKANER 7-Mar-89 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 334005 LDC/OBC/627693 Note:- Candidate who donot receive Call Letter by post , can also report for Trade Test / Interview with a copy of Attestation Form duly completed by downloading form from this web site. -

Indian Hieroglyphs

Indian hieroglyphs Indus script corpora, archaeo-metallurgy and Meluhha (Mleccha) Jules Bloch’s work on formation of the Marathi language (Bloch, Jules. 2008, Formation of the Marathi Language. (Reprint, Translation from French), New Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN: 978-8120823228) has to be expanded further to provide for a study of evolution and formation of Indian languages in the Indian language union (sprachbund). The paper analyses the stages in the evolution of early writing systems which began with the evolution of counting in the ancient Near East. Providing an example from the Indian Hieroglyphs used in Indus Script as a writing system, a stage anterior to the stage of syllabic representation of sounds of a language, is identified. Unique geometric shapes required for tokens to categorize objects became too large to handle to abstract hundreds of categories of goods and metallurgical processes during the production of bronze-age goods. In such a situation, it became necessary to use glyphs which could distinctly identify, orthographically, specific descriptions of or cataloging of ores, alloys, and metallurgical processes. About 3500 BCE, Indus script as a writing system was developed to use hieroglyphs to represent the ‘spoken words’ identifying each of the goods and processes. A rebus method of representing similar sounding words of the lingua franca of the artisans was used in Indus script. This method is recognized and consistently applied for the lingua franca of the Indian sprachbund. That the ancient languages of India, constituted a sprachbund (or language union) is now recognized by many linguists. The sprachbund area is proximate to the area where most of the Indus script inscriptions were discovered, as documented in the corpora. -

2001 Presented Below Is an Alphabetical Abstract of Languages A

Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Census 2001 STATEMENT 1 ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES - 2001 Presented below is an alphabetical abstract of languages and the mother tongues with speakers' strength of 10,000 and above at the all India level, grouped under each language. There are a total of 122 languages and 234 mother tongues. The 22 languages PART A - Languages specified in the Eighth Schedule (Scheduled Languages) Name of language and Number of persons who returned the Name of language and Number of persons who returned the mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother language tongue language tongue 1 2 1 2 1 ASSAMESE 13,168,484 13 Dhundhari 1,871,130 1 Assamese 12,778,735 14 Garhwali 2,267,314 Others 389,749 15 Gojri 762,332 16 Harauti 2,462,867 2 BENGALI 83,369,769 17 Haryanvi 7,997,192 1 Bengali 82,462,437 18 Hindi 257,919,635 2 Chakma 176,458 19 Jaunsari 114,733 3 Haijong/Hajong 63,188 20 Kangri 1,122,843 4 Rajbangsi 82,570 21 Khairari 11,937 Others 585,116 22 Khari Boli 47,730 23 Khortha/ Khotta 4,725,927 3 BODO 1,350,478 24 Kulvi 170,770 1 Bodo/Boro 1,330,775 25 Kumauni 2,003,783 Others 19,703 26 Kurmali Thar 425,920 27 Labani 22,162 4 DOGRI 2,282,589 28 Lamani/ Lambadi 2,707,562 -

Elephantine Confl

EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE THE HINDU DELHI SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 2020 NATION 9 EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE IN BRIEF Weather Watch Elephantine conflict swells in the east Rainfall, temperature & air quality in select metros yesterday Bengal, Odisha and Assam account for about half the fatalities in manelephant conflict, data show Shiv Sahay Singh building up the knowledge Ambala bus stand Kolkata base on elephant ecology”. renamed after Sushma Three States in the eastern Among the reasons for un AMBALA The Ambala city bus stand and northeastern parts of natural deaths of elephants, was renamed after late the country — West Bengal, electrocution is at the top of External Affairs Minister and Odisha and Assam — account the list, accounting for 68% BJP veteran Sushma Swaraj for about half of both human of elephant deaths in the on Saturday. She was born in -

Class-8 New 2020.CDR

Class - VIII AGRICULTURE OF ASSAM Agriculture forms the backbone of the economy of Assam. About 65 % of the total working force is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. It is observed that about half of the total income of the state of Assam comes from the agricultural sector. Fig 2.1: Pictures showing agricultural practices in Assam MAIN FEATURES OF AGRICULTURE Assam has a mere 2.4 % of the land area of India, yet supports more than 2.6 % of the population of India. The physical features including soil, rainfall and temperature in Assam in general are suitable for cultivation of paddy crops which occupies 65 % of the total cropped area. The other crops are wheat, pulses and oil seeds. Major cash crops are tea, jute, sugarcane, mesta and horticulture crops. Some of the crops like rice, wheat, oil seeds, tea , fruits etc provide raw material for some local industries such as rice milling, flour milling, oil pressing, tea manufacturing, jute industry and fruit preservation and canning industries.. Thus agriculture provides livelihood to a large population of Assam. AGRICULTURE AND LAND USE For the purpose of land utilization, the areas of Assam are divided under ten headings namely forest, land put to non-agricultural uses, barren and uncultivable land, permanent pastures and other grazing land, cultivable waste land, current fallow, other than current fallow net sown area and area sown more than once. 72 Fig 2.2: Major crops and their distribution The state is delineated into six broad agro-climatic regions namely upper north bank Brahmaputra valley, upper south bank Brahmaputra valley, Central Assam valley, Lower Assam valley, Barak plain and the hilly region. -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

The British Advent in Balochistan

The British Advent in Balochistan Javed Haider Syed ∗∗∗ An Abstract On the eve of the British advent, the social and economic infrastructure of Balochistan represented almost all characteristics of a desert society, such as isolation, group feeling, chivalry, hospitality, tribal enmity and animal husbandry. There was hardly any area in Balochistan that could be considered an urban settlement. Even the capital of the state of Kalat looked like a conglomeration of mud dwellings with the only royal residence emerging as a symbol of status and power. In terms of social relations, economic institutions, and politics, society demonstrated almost every aspect of tribalism in every walk of life. This paper, therefore, presents a historical survey of the involvement of Balochistan in the power politics of various empire- builders. In particular, those circumstances and factors have been examined that brought the British to Balochistan. The First Afghan War was fought apparently to send a message to Moscow that the British would not tolerate any Russian advances towards their Indian empire. To what extent the Russian threat, or for that matter, the earlier French threat under Napoleon, were real or imagined, is also covered in this paper. A holistic account of British advent in Balochistan must begin with “The Great Game” in which Russia, France, and England, were involved. Since the time of Peter the Great (1672-1725), the Russians were desperately looking for access to warm waters. The Dardanelles were guarded by Turkey. After many abortive attempts, Russians concentrated on the Central Asian steppes in order to find a route to the Persian Gulf as well as the Indian Ocean. -

Some Select Folktales of Aimol

================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 17:10 October 2017 UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ================================================================ Some Select Folktales of Aimol Chongom Damrengthang Aimol, Ph.D. ======================================================== Aimol Aimol is one of the recognized tribes of Manipur. It was recognized on 29th October, 1956 vide notification no. 2477, under Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Aimol as a tribe is endogamous and possesses a common dialect, a common tradition of origin and common beliefs and ideas. The total population of Aimol according to Census- 2011 is 4,640 (According to Chairman, Aimol Literature Society, Manipur). The Aimol tribe is found in Chandel, Churachandpur, and Senapati districts of Manipur. In the entire state, there are 15 Aimol villages, of which eleven are in Chandel district (Khullen, Chandonpokpi, Ngairong, Khodamphai, Tampak, Chingnunghut, Khunjai, Kumbirei, Satu, Khudengthabi and Unapal), two in Churachandpur district (Kha-Aimol and Louchunbung) and another two in Senapati district (Tuikhang, Kharam-Thadoi). Aimol has no written literature except some books, gospel songs, Bible, which is translated from English and A Descriptive Grammar of Aimol written by M. Shamungou Singh, an unpublished Ph.D. thesis of Manipur University, Imphal. There is no native script. Adapted Roman script is used for writing books and other journals, etc. The teaching of Aimol has not been introduced in any private or government schools. For communication with other communities Aimol people use Manipuri or Meiteilon which is the lingua franca of Manipur State. Aimol has no work which documents of folk songs and folktales. So this paper tries to present out some of the folktales of Aimol which are oral tales, and are not available in written record.