The British Advent in Balochistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Buffer Zone, Colonial Enclave, Or Urban Hub?

Working Paper no. 69 - Cities and Fragile States - BUFFER ZONE, COLONIAL ENCLAVE OR URBAN HUB? QUETTA :BETWEEN FOUR REGIONS AND TWO WARS Haris Gazdar, Sobia Ahmad Kaker, Irfan Khan Collective for Social Science Research February 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © H. Gazdar, S. Ahmad Kaker, I. Khan, 2010 24 Crisis States Working Paper Buffer Zone, Colonial Enclave or Urban Hub? Quetta: Between Four Regions and Two Wars Haris Gazdar, Sobia Ahmad Kaker and Irfan Khan Collective for Social Science Research, Karachi, Pakistan Quetta is a city with many identities. It is the provincial capital and the main urban centre of Balochistan, the largest but least populous of Pakistan’s four provinces. Since around 2003, Balochistan’s uneasy relationship with the federal state has been manifested in the form of an insurgency in the ethnic Baloch areas of the province. Within Balochistan, Quetta is the main shared space as well as a point of rivalry between the two dominant ethnic groups of the province: the Baloch and the Pashtun.1 Quite separately from the internal politics of Balochistan, Quetta has acquired global significance as an alleged logistic base for both sides in the war in Afghanistan. This paper seeks to examine different facets of Quetta – buffer zone, colonial enclave and urban hub − in order to understand the city’s significance for state building in Pakistan. State-building policy literature defines well functioning states as those that provide security for their citizens, protect property rights and provide public goods. States are also instruments of repression and the state-building process is often wrought with conflict and the violent suppression of rival ethnic and religious identities, and the imposition of extractive economic arrangements (Jones and Chandaran 2008). -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Arain (Muslim traditions) in Pakistan Arora (Muslim traditions) in Pakistan Population: 9,830,000 Population: 215,000 World Popl: 9,963,600 World Popl: 215,700 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Arain People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Imran Ali Arain "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Awan in Pakistan Baloch in Pakistan Population: 5,229,000 Population: 7,380,000 World Popl: 5,249,000 World Popl: 7,438,900 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other People Cluster: Baloch Main Language: Punjabi, Western Main Language: Balochi, Eastern Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Galen Frysinger Source: Khalid Mahmood - Wikimedia "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Baloch -

Balochistan Economic Report Background Paper on Social Structures and Migration

First Draft - Do Not Cite TA4757-PAK: BALOCHISTAN ECONOMIC REPORT Balochistan Economic Report Background Paper on Social Structures and Migration Haris Gazdar 28 February 2007 Collective for Social Science Research 173-I Block 2, PECHS, Karachi 75400, Pakistan [email protected] The author gratefully acknowledges research assistance provided by Azmat Ali Budhani, Sohail Javed, Hussain Bux Mallah, and Noorulain Masood. Irfan Khan provided guidance with resource material and advised on historical references. Introduction Compared with other provinces of Pakistan, and Pakistan taken as a whole, Balochistan’s economic and social development appears to face particularly daunting challenges. The province starts from a relatively low level – in terms of social achievements such as health, education and gender equity indicators, economic development and physical infrastructure. The fact that Balochistan covers nearly half of the land area of Pakistan while accounting for only a twentieth of the country’s population is a stark enough reminder that any understanding of the province’s economic and social development will need to pay attention to its geographical and demographic peculiarities. Indeed, remoteness, environmental fragility and geographical diversity might be viewed as defining the context of development in the province. But interestingly, Balochistan’s geography might also be its main economic resource. The low population density implies that the province enjoys a potentially high value of natural resources per person. The forbidding topography is home to rich mineral deposits – some of which have been explored and exploited while yet others remain to be put to economic use. The land mass of the province endows Pakistan with a strategic space that might shorten trade and travel costs between emerging economic regions. -

Project Title to Be Centred

Environmental Assessment Report Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 37192 August 2009 PAK: Multitranche Financing Facility Power Transmission Enhancement Investment Program, Tranche 1 Sub Project No. 20 220 kV Dera Ghazi Khan - Loralai Double Circuit Transmission Line Subproject Prepared by National Transmission and Despatch Company for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 30 May 2009) Currency Unit – Pakistan rupee/s (Pre/PRs) PRe1.00 = $.0080 $1.00 = PRs79.80 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank dB(decibel) – sound level measure EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan IEC – International environmental consultants IEE – initial environmental examination LARP – land acquisition and resettlement plan MFF – Multitranche Financing Facility PCB – Polychlorinated biphenyls PEPA – Punjab Environmental Protection Agency PEPAct – Pakistan Environmental Protection Act 1997 (as regulated and amended) PMU – project management unit ROW – right of way WMP – waste management plan DEFINITIONS Barren Land – Land which has not been cultivated and was lying barren at the time of field survey for this IEE Cropped land – Land which was under agricultural crops at the time of field survey for this IEE. Landowner – Person(s) holding legal title to property on the electric transmission line route from whom the Company is seeking, or has obtained, a temporary or permanent easement, or any person(s) legally authorized by a landowner to make decisions regarding the mitigation or restoration of agricultural impacts to such landowner(s) property. -

Socio-Political Study of District Dera Ghazi Khan 1988-1999 Submitted By

Socio-Political Study of District Dera Ghazi Khan 1988-1999 Session (2015-2017) Submitted By: Abdul Majeed Submitted to: Dr. Akbar Malik Roll No: 15 Class: M.Phil. Pakistan Studies Department of Pak Studies The Islamia University of Bahwalpur i Socio-Political Study of District Dera Ghazi Khan 1988-1999 Table of Contents Sr.No. Page No. Dedication II Statement &Declaration III Certificate IV Acknowledgment V Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 1 : 10 Hstorical Background of District D. G. Khan 1.1 Hostory of Dera Gahzi Khan. 1.1 Tehsil D. G. Khan 1.2 Tehsil Taunsa 1.3 Tribal Area 1.4 Kot Chuuta Chapter 2 : 30 Social Study of District D. G. Khan 2.1 Rural Area 2.2 Tribal Structure 2.3 Customary Practices vii 2.4 Historical and Tourist places Chapter 3 : 56 Political Parties and Politics of D. G. Khan (1988-1999) 3.1 Prominent Political Parties 3.2 The nature of National and Provincial Constituencies 3.2 Electoral History and Politics 3.3 Activities of Local Government (1988-1999) 3.3 Element affecting the Electoral Politics Chapter 4 : 86 Political Families and Personalities of D.G. Khan and their Impact (1988-1999) 4.1 Political families of District D. G. Khan 4.1.1 Mazari 4.1.2 Khosa 4.1.3 The Leghari's 4.1.4 Gorchani 4.2 Political Impact of Personalities Conclusion 101 Appendix 108 Bibliography 117 viii Abstract This research deals with the facts, regarding to socio-political growth and development in D. G. Khan from 1988 to 1999. -

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

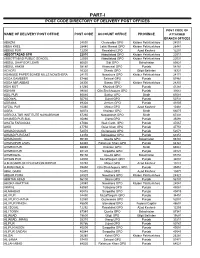

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Tsunami Heights and Limits in 1945 Along the Makran Coast

https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2021-53 Preprint. Discussion started: 5 March 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Tsunami heights and limits in 1945 along the 2 Makran coast estimated from testimony 3 gathered seven decades later in Gwadar, Pasni 4 and Ormara 5 Hira Ashfaq Lodhi1, Shoaib Ahmed2, Haider Hasan2 6 1Department of Physics, NED University of Engineering & Technology, Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 7 2 Department of Civil Engineering, NED University of Engineering & Technology, Karachi, 75270, Pakistan 8 Correspondence to: Hira Ashfaq Lodhi ([email protected]) 9 Abstract. 10 The towns of Pasni and Ormara were the most severely affected by the 1945 Makran tsuami. The water inundated almost a 11 kilometer at Pasni, engulfing 80% huts of the town while at Ormara tsunami inundated two and a half kilometers washing 12 away 60% of the huts. The plate boundary between Arabian plate and Eurasian plate is marked by Makran Subduction Zone 13 (MSZ). This Makran subduction zone in November 1945 was the source of a great earthquake (8.1 Mw) and of an associated 14 tsunami. Estimated death tolls, waves arrival times, extent of inundation and runup remained vague. We summarize 15 observations of tsunami through newspaper items, eye witness accounts and archival documents. The information gathered is 16 reviewed and quantized where possible to get the inundation parameters in specific and impact in general along the Makran 17 coast. The quantization of runup and inundation extents is based on a field survey or on old maps. 18 1 Introduction 19 The recent tsunami events of 2004 Indian Ocean (Sumatra) tsunami, 2010 (Chile) and 2011 (Tohoku) Pacific Ocean tsunami 20 have highlighted the vulnerability of coastal areas and coastal communities to such events. -

Ancient Regions, New Frontier the Prehistory of the Durand Line in Baluchistan

Internationales Asienforum, Vol. 44 (2013), No. 1–2, pp. 7–24 Ancient Regions, New Frontier The Prehistory of the Durand Line in Baluchistan JAKOB RÖSEL* Abstract The prehistory of the Durand Line is complicated, involving new forms of tribal al- legiance-building, tribal and localised state-building and, finally, regional empire- building. A new tribal as well as mercantile religion and civilisation, Islam, gave rise to new patterns of trade and a new crossroads and commercial centre: Kalat. With the decline of the Mughals a Kalat state based on a local dynasty and two tribal fed- erations emerged as a semi-independent state. The British Empire ultimately strength- ened and enlarged, balanced and controlled this tribal and regional state. Thanks to the British the Khan of Kalat controlled most of present-day Baluchistan. From the 1870s the construction of this imperial state served new geostrategic designs: the Khan of Kalat conceded control over the Bolan Pass as well as Quetta to the British Empire. It was this imperial bridgehead, called British Baluchistan, which served as the cornerstone for a forward border policy and, ultimately, the Durand Line. Keywords Frontiers, imperialism, British India, Baluchistan, Durand Line Introduction A frontier, border or boundary can have various forms and functions. The actual artefact is only the empirical, spatial manifestation of versatile social or political, cultural or economic intentions, designs or strategies. Borders serve an offensive or defensive function. They are inclusive or exclusive. They can operate as the exoskeleton of an emerging state. They can either create or fail to create and demarcate ethnic loyalties or political identities. -

The Socio-Educational Scenario of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in the Early Decade of the 20Th Century

THE SOCIO-EDUCATIONAL SCENARIO OF THE KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA, IN THE EARLY DECADE OF THE 20TH CENTURY Muhammad Sohail Khan Abstract The paper explores the socio-educational scenario of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, then N.W.F.P during British rule, and explains how wretchedly this province was treated in education. Before its establishment in 1901, being part of the Punjab province, the five districts that are Peshawar, Hazara, Dera Ismail Khan, Kohat and Bannu were the most backward amongst 31 districts. Similarly, the province was the last in education amongst all provinces of the India.Pashtuns, were ignored in education by the Britishers, due to their geo- strategic location. It was the gateway of the invasions, so there must have been no or low resistance in the strategic way of it, which needed illiterate subordinates. Their energies were diverted towards other social multiplicities, detached them from trade, commerce, business and decision making stakeholder ship. Several primary schools in the province were offered to be established after successful participation of the villagers in the World War 1. Key words: Socio-educational, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 20th Century Introduction The Indian North-West Frontier region was faced with multifaceted issues, including social and educational during the 19th Century.1 The British annexation of the Punjab, in 1849, brought them in direct contact with the inhabitants of Pashtun land. For this region, they Assistant Professor Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan 128 devised rather revised their policy and initiated the concept of Tribal and Settled areas with their sole objective to serve their ulterior motive of civilizing this uncivilized race. -

1 TRIBE and STATE in WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis

1 TRIBE AND STATE IN WAZIRISTAN 1849-1883 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for PhD degree at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1997 ProQuest Number: 10673067 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673067 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT The thesis begins by describing the socio-political and economic organisation of the tribes of Waziristan in the mid-nineteenth century, as well as aspects of their culture, attention being drawn to their egalitarian ethos and the importance of tarburwali, rivalry between patrilateral parallel cousins. It goes on to examine relations between the tribes and the British authorities in the first thirty years after the annexation of the Punjab. Along the south Waziristan border, Mahsud raiding was increasingly regarded as a problem, and the ways in which the British tried to deal with this are explored; in the 1870s indirect subsidies, and the imposition of ‘tribal responsibility’ are seen to have improved the position, but divisions within the tribe and the tensions created by the Second Anglo- Afghan War led to a tribal army burning Tank in 1879.