Arthur Miller: Reception and Influence in China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translation of Western Contemporary Literary Theories to China

Linguistics and Literature Studies 5(4): 225-241, 2017 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2017.050401 Theory Travel: Translation of Western Contemporary Literary Theories to China Lu Jie1,2 1Foreign Language College, Chengdu University of Information Technology, China 2College of Literature and Journalism, Sichuan University, China Copyright©2017 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract From the beginning of the 20th century, many previous paralleled analogical researching paradigm caused Western contemporary literary theories, including formalism, the problem of “over-simplified comparison” and deficiency the New Criticism, phenomenology, hermeneutics, reception of “mode of seeking commonness”, and the key to solving aesthetics, structuralism, deconstruction, psychoanalysis, the problem and make up for it is to “explore a way of post-colonialism and Western Marxism, have been translated influential study in comparative poetics” from perspectives into Chinese. Translation of those Western literary theories of clarifying Chinese elements in Western theories and has undergone four phases in China over a century’s travel: noticing variations in theory travel. The research on the commencement and development from the early 1920s to translation of Western contemporary theories is inseparable the late 1940s, the frustration and depression from the late and significant for the study of “variations in theory travel.” 1940s to the end of 1970s, the recovery and revival from the Through the research on China’s translation and introduction late 1970s to the late 1990s as well as the sustained of Western contemporary theories, the essay tries to probe development and new turn from the beginning of the 21st and discover some factors that manipulate Chinese scholars’ Century till now. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography Note: This is a very selective list, with emphasis on recent Chinese publications. English titles are confi ned to those consulted by the author. Chinese titles are arranged alphabetically according to pinyin . The list is in seven parts: I. Bibliographies II. Periodicals III. Encyclopedias, dictionaries IV. Anthologies a. Comprehensive b. Fiction c. Poetry d. Drama e. Essays f. Miscellaneous V. General studies VI. Recent translations VII. Shakespeare studies I. Bibliographies ഭᇦࠪ⡸һъ㇑⨶ተ⡸ᵜമҖ侶㕆: 㘫䈁ࠪ⡸ཆഭਔި᮷ᆖ㪇ⴞᖅ 1949–1979, ѝॾҖተ, 1980 (Copyright Library, State Publishing Bureau, ed. Bibliography of Published Translations of Foreign Classics, 1949–1979) ѝഭ⽮Պ、ᆖ䲒ཆഭ᮷ᆖ⹄ウᡰ㕆: ᡁഭᣕ࠺ⲫ䖭Ⲵཆഭ᮷ᆖ૱઼䇴䇪᮷ㄐⴞᖅ㍒ᕅ (1978–1980), ेӜ, 1980 © Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing Co., Ltd 171 and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Z. Wang, Degrees of Affi nity, China Academic Library, DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-45475-6 172 Select Bibliography (Foreign Literature Research Institute, Academy of Social Sciences, ed. Bibliography of Foreign Literary Works and Critical Articles on them Published in Chinese Periodicals, 1978–1980) Deeney, John J. ed. Chinese English Comparative Literature Bibliography: A Pedagogical Arrangement of Sources in English, Tamkang Review , Vol, XII, No. 4 (Summer 1982) II. Periodicals (A, annual; 2/year, biannual; Q, quarterly; Bm, bimonthly; M, monthly; where names have changed, only present ones are given.) ᱕仾䈁ы (Spring Breeze Translation Miscellany) 2/year Shenyang 1980— ᖃԓ㣿㚄᮷ᆖ (Contemporary Soviet Literature) Bm -

Report Title Paasch, Carl = Paasch, Karl Rudolf

Report Title - p. 1 of 545 Report Title Paasch, Carl = Paasch, Karl Rudolf (Minden 1848-1915 Zürich) : Deutscher Geschäftsmann, antisemitischer Publizist Bibliographie : Autor 1892 Paasch, Carl. Die Kaiserlich deutsche Gesandtschaft in China : eine Denkschrift über den Fall Carl Paasch für die dt. Landesvertretungen, insbesondere den Reichstag. (Leipzig : Im Selbstverlage des Verfassers, 1892). https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN610 163698&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&DMDID=. [Nachdem er sich bei Geschäften in China betrogen glaubte, verfasste Paasch eine Schrift, in welcher er die Beziehungen des deutschen Gesandten in China, Max von Brandt, zu Geschäftsleuten und Bankiers verurteilte. Theodor Fontane bezeichnete Paasch in einem Brief als Verrückten]. [Wik,WC] Paauw, Douglas S. = Paauw, Douglas Seymour (1921-) Bibliographie : Autor 1951 Bibliography of modern China : works in Western languages (revised) : section 5, economic. Compiled by Douglas S. Paauw and John K. Fairbank for the Regional Studies Program on China. (Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University, 1951). Pabel, Hilmar (1910-2000) : Photojournalist Bibliographie : Autor 1986 Pabel, Romy ; Pabel, Hilmar. Auf Marco Polos Spuren : Expedition Seidenstrasse. (München : Süddeutscher Verlag, 1986). [Bericht ihrer Reise 1985, Shanghai, Xi'an, Lanzhou, Jiayuguan, Grosse Mauer, Dunhuang, Ruoqiang, Qiemo, Minfeng, Hotan, Yecheng, Yarkant, Kaxgar, Indien]. [Cla] Pabel, Romy (um 1985) : Gattin von Hilmar Pabel Bibliographie : Autor 1986 Pabel, Romy ; Pabel, Hilmar. Auf Marco Polos Spuren : Expedition Seidenstrasse. (München : Süddeutscher Verlag, 1986). [Bericht ihrer Reise 1985, Shanghai, Xi'an, Lanzhou, Jiayuguan, Grosse Mauer, Dunhuang, Ruoqiang, Qiemo, Minfeng, Hotan, Yecheng, Yarkant, Kaxgar, Indien]. [Cla] Pabst, Georg Wilhelm (Raudnitz, Böhmen 1885-1967 Wien) : Österreichischer Filmregisseur Biographie 1938 Le drame de Shanghai. Un film de G.W. Pabst ; d'après l'oeuvre de O.P. -

"Experimenting with Dance Drama: Peking Opera Modernity, Kabuki Theater Reform and the Denishawn’S Tour of the Far East"

Journal of Global Theatre History ISSN: 2509-6990 Issue 1, Number 2, 2016, pp. 28-37 Catherine Vance Yeh "Experimenting with Dance Drama: Peking Opera Modernity, Kabuki Theater Reform and the Denishawn’s Tour of the Far East" Abstract During the 1910s and 20s, Peking opera underwent a fundamental transformation from a performing art primarily driven by singing to one included acting and dancing. Leading this new development were male actors playing female roles, with Mei Lanfang as the most outstanding example. The acknowledged sources on which these changes drew were the encounter with Western style opera. The artistic and social values carrying these changes, however, suggest that Peking opera underwent a qualitative reconceptualization that involved a critical break with its past. This paper will explore the artistic transformation of Peking opera of the 1910s-20s by focusing on the three areas of contact Paris, Japan and the US. It will argue that the particular artistic innovation in Peking can only be fully understood and appraised in the context of global cultural interaction. It suggests that a new assessment of the modernist movement is needed that sees it as a part of a global trend rather than only as a European phenomenon. Author Catherine Vance Yeh is Professor of Modern Chinese Literature and Transcultural Studies at Boston University. Her research focuses on the global migration of literary forms; the transformation of theater aesthetics in transcultural interaction, and entertainment culture as agent of social change. Her publications include Shanghai Love: Courtesans, Intellectuals and Entertainment Culture, 1850-1910; and The Chinese Political Novel: Migration of a World Genre. -

From Opium to Chrysanthemums Families, As Some Clans Supported (Or Were Forced to >> Directed by Pea Holmquist and Suzanne Khardalian

A PUBLICATION OF THE ASIAN EDUCATIONAL MEDIA SERVICE Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies ✦ University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign A E M S Vol. 8, No. 1 News and Reviews Spring 2005 destroyed Hmong villages and disrupted Hmong From Opium to Chrysanthemums families, as some clans supported (or were forced to >> Directed by PeA Holmquist and Suzanne Khardalian. 2000. 75 minutes. support) the CIA war against the communists and some clans supported the victorious Pathet Lao Drug Story who formed the socialist Lao PDR in 1975. Stock images of the war add texture to the film, but the >> From the series, Winds of Change. Directed by Luu Hong Sôn. 1999. 20 minutes. complex role of the Hmong still needs more con- textualization for viewers unfamiliar with the hese two films provide very different per- The Hmong, very much a despised minority from secret war in Laos. The war resulted in massive T spectives on the opium addiction of the the lowland Thai perspective, paid an “opium tax” population movements as some Hmong escaped as Hmong people of northern Vietnam, Lao PDR, to the Thai police, and were constantly wary of refugees to Thailand and eventually resettled in and Thailand. Viewers will come to appreciate the unscrupulous opium traders who would take the United States and elsewhere. The film follows lifestyle and culture of the advantage of people like the Hmong with no one addicted opium farmer who struggles to feed Hmong, as they cope with citizenship or identity cards. Racism against the his family and his habit, and juxtaposes his Review rapid changes in their Hmong goes unmentioned in the film. -

Dissertation (Fan Liao)

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Paradoxical Peking Opera: Performing Tradition, History, and Politics in 1949-1967 China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Drama and Theatre by Fan Liao Committee in charge: University of California, San Diego Professor Janet L. Smarr, Chair Professor Paul G. Pickowicz, Co-Chair Professor Nancy A. Guy Professor Marianne McDonald Professor John S. Rouse University of California, Irvine Professor Stephen Barker 2012 The Dissertation of Fan Liao is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego University of California, Irvine 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents……………………………………………………………....................iv Vita………………………………………………………………………………………...v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………...vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter One………………………………………….......................................................29 Reform of Jingju Old Repertoire in the 1950s Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………...81 Making History: The Creation of New Jingju Historical Plays Chapter Three…………………………………………………………………………...135 Inventing Traditions: The Creation of New Jingju Plays with Contemporary Themes Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...204 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………….211 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………229 iv VITA 2003 -

Introduction to Drum Rhythm on Peking Opera Stage

Introduction to Drum Rhythm on Peking Opera Stage Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophische Fakultät der Universität zu Köln Vorgelegt von Lan Ying aus Gui Zhou, China Prüfer Prof. Dr. Stefan Kramer Prof. Dr.Peter W. Marx Prof. Dr. Frank Hentschel Prof. Dr.Uwe Seifert Prof. Dr. Felix Wemheuer Prof. Dr. Faderico Spineet Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 10.12.2014 Content 1 Introduction 1 Peking Opera and its drum rhythm………………………………………………...3 2 Time in drum rhythm on Peking Opera stage……………………………………...4 3 Drum rhythm on Peking Opera stage and its linguistic structure……………….....7 4 Drum rhythm, as communicative device, on Peking Opera stage………………..10 5 Theory and Method…………………………………………………………….....13 2 Time module in rhythm on the Peking Opera stage 2.1 A Brief overview of percussion instruments and their playing methods………..18 2.2 Time module in drum rhythm on Peking Opera stage…………………………..22 3 Drum rhythm and its linguistic structure 3.1 The Semantics of Drum rhythm…………………………………………………32 3.2 The Levels of meaning on drum rhythm………………………………………33 3.3 Metafunctional analysis of drum rhythm………………………………………..39 3.4 The Linguistics characteristics of drum rhythm………………………………...42 3.5 Drum rhythm signals and significations………………………………………...54 3.6 Drum rhythm on Peking Opera stage and metadiscourse in linguistics………58 3.6.1 Categorizations of metadiscourse in linguistics………………………....58 3.6.2 Categorizations of drum rhythm on Peking Opera stage………………..63 3.6.3 The Unique features of drum rhythm…………………………………....94 3.7 Summary -

Opera, Beijing Jīngjù 京 剧

◀ Open Door Policy Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. Opera, Beijing Jīngjù 京 剧 Jingju (Beijing Opera) is characterized by impersonators (nandan, literally “male female charac- simple and spare stage sets, highly stylized ters”). A system of indenture developed by which entre- gestures and movement, and elaborate cos- preneurs bought little boys in Jiangsu and Anhui provinces tumes and headgear replicating those worn in under contract and took them to Beijing, teaching them the Jingju arts. The Taiping Rebellion (1851–1866) stopped the Ming-dynasty; it is historically renowned the practice of bringing boys from the south, but acting for the skill with which women’s roles were talent ran in families, and boys could be found in Beijing once portrayed by female impersonators. to carry on the tradition. By the 1830s the nandan were joined by the great laosheng (old male) actors. The most famous was Cheng ingju (Beijing Opera or Peking Opera) is the style of Changgeng (1811– 1880) from Anhui, who led the Sanq- regional opera that originated in Beijing late in the ing company from about 1845 until his death and devel- eighteenth century. Jingju is sometimes regarded oped the laosheng arts to such a degree that many still call as a national Chinese theater. It belongs to the Pihuang him “the father” of Jingju. Many plays were considered system of regional operas, which combines the two musi- the property of particular actors, but the playwrights are cal styles: xipi, which is vigorous and bright, and Erhuang, rarely known. more lyrical and dark. A man in a park sings in the style of a Beijing Origins and Opera performer. -

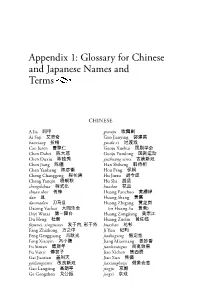

Appendix 1: Glossary for Chinese and Japanese Names and Terms

A p p e n d i x 1 : G l o s s a r y f o r C h i n e s e and Japanese Names and Terms C H I N E S E A J i a 棎䟁 gewuju 㷛咭⓶ A i S i q i 唍㊬⯖ G u o J i a n y i n g 捼ㆉ喀 banxiang 㓽䦇 guodu xi 扖䂰㒞 C a o J u r e n 㦈勩⅐ G u o j u X u e h u i ⦌⓶ⷵ↩ Chen Dabei 棗⮶㍁ G u o j u Y u n d o n g ⦌⓶扟┷ Chen Duxiu 棗䕻䱏 guzhuang xinxi ♳孔㠿㒞 C h e n J i a n g 棗䠕 H a n S h i h e n g 橸∜㫐 C h e n Y a n h e n g 棗ㇵ嫰 H o u F e n g ∾㨺 Cheng Changgeng 䲚栎ㄩ H u J i n x u 印⅙壩 C h e n g Y a n q i u 䲚䪩䱚 H u S h i 印抑 chengshihua 䲚㆞▥ huadan 啀㡵 chuan shen ↯䯭 H u a n g F a n c h u o 煓㡨兿 dan 㡵 H u a n g S h a n g 煓宂 daomadan ⒏泻㡵 H u a n g Z h i g a n g 煓唬⼦ D a t o n g Y u e h u i ⮶⚛⃟↩ (or Huang Su 煓侯) D i y i W u t a i 䶻咭♿ H u a n g Z o n g j i a n g 煓⸦㻮 D u H e n g 㧫嫰 H u a n g Z u o l i n 煓⇟ fayunei, xingyuwai ♠ℝ␔, ㇱℝ⮥ huashan 啀嫺 F a n g Z h i z h o n g 㡈⃚₼ Ji Yun 儹㢏 F e n g G e n g g u a n g 勎⏘ jiadingxing ⋖⸩㊶ F e n g X i a o y i n ⺞椟 J i a n g M i a o x i a n g ⱫⰨ氨 F u S i n i a n ⌔㠾 jianlixiaoguo 梃䱊㟗㨫 F u Y u n z i ⌔啇 J i a o X i c h e n 䎵導房 G a i J i a o t i a n 䥥♺⮸ J i a o X u n 䎵㈹ gailiangxinxi 㟈哾㠿㒞 jiaxianghuiyi ⋖廰↩㎞ Gao Langting 浧㦦ℼ jingju ℻⓶ G e G o n g z h e n 㒗⏻㖾 jingxi ℻㒞 224 Mei Lanfang and the International Stage kunqu 㢕㦁 S h i s a n d a n ◐ₘ㡵 kunju 㢕⓶ (or Hou Junshan ∾≙⼀) laosheng 劐䞮 shizhuang xinxi 㢅孔㠿㒞 L i F e i s h u 㧝㠟♣ S u n H u i z h u ⷨ㍯㪀 L i J i n s h e n 㧝㾴愺 T a n X i n p e i 庼曺⪈ L i K a i x i a n 㧝⏗ T a n g X i a n z u 㻳㣍䯥 Li Shizeng 㧝䪂㦍 tangma 怮泻 L i T a o h e n 㧝䀪䡤 T i a n H a n 䞿㻘 L i a n g Q i c h a o 㬐⚾怔 Wang Guangqi 䘚⏘䯗 liangxiang -

Nandan in the Ming Dynasty a Thesis Submitted to The

NANDAN IN THE MING DYNASTY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THEATRE MAY 2012 By Yan Ma Thesis Committee: Julie Iezzi, Chairperson Kirstin Pauka Giovanni Vitiello Keywords: Nandan, Kunqu, Ming Dynasy ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to express my sincere thanks to the chair of the committee, Professor Julie Iezzi, for her continuous support and guidance of my research. I am grateful to the members of my thesis committee, Professor Kirstin Pauka and Giovanni Vitiello for their help on this thesis. Professor Giovanni Vitiello with immense knowledge in Chinese literature gave me a lot of inspiration and valuable suggestions. I appreciate Professor Kirstin Pauka’s patience and help especially in the writing process. I would also like to thank Professor Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak and Lurana Donnels O’Malley for their help in the early stages of research. Dr. Jintang Luo helped me a great deal in understanding the historical records, for which I am thankful as well. Also, many thanks to Ms. Xiaohui Bao in China, who directed me to appreciate traditional Chinese theatre and encouraged me to pursue a Masters degree in the Dept. of Theatre and Dance at UHM. Last but not least, I dedicate this work to my parents, for supporting and encouraging me throughout my life. i ABSTRACT Nan means male, and dan is the generic name of female roles in xiqu (traditional Chinese theatre). The term nandan refers to a male actor who performs female roles in xiqu. -

Guanda Wu's MA Thesis

ABSTRACT NEGOTIATIONS OF CULTURAL AESTHETICS IN THE “REFORMS” OF MEI LANFANG AND THE “MEI PARTY” MEMBERS TO JINGJU IN CHINA’S EARLY REPUBLICAN ERA (1912-1937) by Guanda Wu China’s early Republican stage witnessed the rise of Mei Lanfang and his “reformed” jingju plays. Mei’s successful career in the early Republican era not only helped him to enjoy great popularity on the domestic stage, but also assisted traditional Chinese theatre in gaining a valuable confirmation from the West. Without a full awareness of the fundamental differences between Western and Chinese theatrical aesthetics, the “Mei Party” intellectuals allowed themselves to be appropriated by Western colonial aesthetics and the Western gaze. Their approach applied Western drama’s aesthetic principle to “reform” traditional jingju performance within China, while they plunged into a system of Orientalization that fit Western reception of traditional Asian art. In both cases, the traditional Chinese art’s enduring cultural identity was threatened by the Western cultural dominancy in a postcolonial context. NEGOTIATIONS OF CULTURAL AESTHETICS IN THE “REFORMS” OF MEI LANFANG AND THE “MEI PARTY” MEMBERS TO JINGJU IN CHINA’S EARLY REPUBLICAN ERA (1912-1937) A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Theatre by Guanda Wu Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2010 Advisor ___________________________ (Dr. Ann Elizabeth Armstrong) Reader ___________________________ (Dr. Andrew Gibb) Reader -

A Study of Two Selected Chamber Works for Piano and Violin by Bright Sheng

A Study of Two Selected Chamber Works for Piano and Violin by Bright Sheng A Night at the Chinese Opera and Three Fantasies by Zhou Jiang A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Russell Ryan, Chair Andrew Campbell Ellon Carpenter ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 © Zhou Jiang All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Our world has become smaller due to globalization and frequent cultural exchange between different countries. As a result, classical music is becoming increasingly global. There are a significant number of Chinese composers, including Tan Dun, Chen Yi, Zhou Long, and Bright Sheng, who have gained international attention. For a modern performer, familiarity with music outside of the Western canon is increasingly important. Bright Sheng is an internationally renowned Chinese-American composer who blends the heritage of traditional Chinese musical elements, traditional instruments, Chinese Opera and folk melodies with Western musical techniques. He infuses Chinese character into his works and introduces Chinese music to the Western classical music world. In this paper, I discuss two of Bright Sheng’s pieces: A Night at the Chinese Opera and Three Fantasies. Both works were composed in 2005 and are the only two compositions he wrote for violin and piano. Most pianists are not familiar with how to transfer or imitate the sounds of traditional Chinese instruments on Western musical instruments. The paper examines traditional Chinese techniques for Western instruments from A Night in Chinese Opera. Three Fantasies contains three distinct musical characters related to different musical elements from different regions of China.