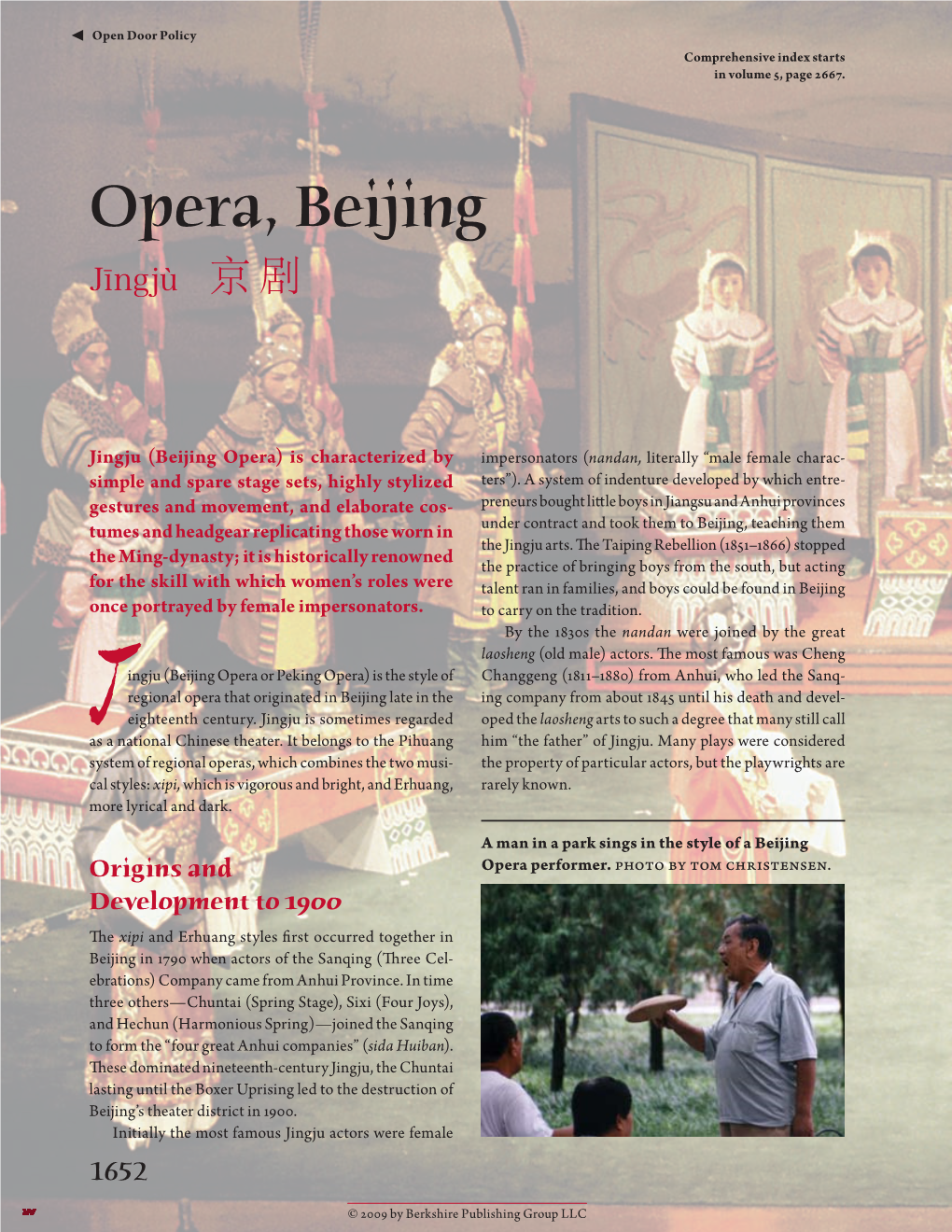

Opera, Beijing Jīngjù 京 剧

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translation of Western Contemporary Literary Theories to China

Linguistics and Literature Studies 5(4): 225-241, 2017 http://www.hrpub.org DOI: 10.13189/lls.2017.050401 Theory Travel: Translation of Western Contemporary Literary Theories to China Lu Jie1,2 1Foreign Language College, Chengdu University of Information Technology, China 2College of Literature and Journalism, Sichuan University, China Copyright©2017 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract From the beginning of the 20th century, many previous paralleled analogical researching paradigm caused Western contemporary literary theories, including formalism, the problem of “over-simplified comparison” and deficiency the New Criticism, phenomenology, hermeneutics, reception of “mode of seeking commonness”, and the key to solving aesthetics, structuralism, deconstruction, psychoanalysis, the problem and make up for it is to “explore a way of post-colonialism and Western Marxism, have been translated influential study in comparative poetics” from perspectives into Chinese. Translation of those Western literary theories of clarifying Chinese elements in Western theories and has undergone four phases in China over a century’s travel: noticing variations in theory travel. The research on the commencement and development from the early 1920s to translation of Western contemporary theories is inseparable the late 1940s, the frustration and depression from the late and significant for the study of “variations in theory travel.” 1940s to the end of 1970s, the recovery and revival from the Through the research on China’s translation and introduction late 1970s to the late 1990s as well as the sustained of Western contemporary theories, the essay tries to probe development and new turn from the beginning of the 21st and discover some factors that manipulate Chinese scholars’ Century till now. -

The Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in the Changing World, by Li Ruru

The Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in the Changing World, by Li Ruru Author Mackerras, Colin Published 2010 Version Version of Record (VoR) Copyright Statement © 2010 CHINOPERL. The attached file is reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Please refer to the journal's website for access to the definitive, published version. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/71170 Link to published version https://chinoperl.osu.edu/journal/back-volumes-2001-2010 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au CHINOPERL Papers No. 29 The Soul of Beijing Opera: Theatrical Creativity and Continuity in the Changing World. By Li Ruru, with a foreword by Eugenio Barba. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010, xvi + 335 pp. 22 illus. Paper $25.00; Cloth $50.00. Among the huge advances made in studies of Chinese theatre in European languages over recent decades, those on the genre now normally called jingju 京劇 in Chinese and referred to in English as Peking opera or Beijing opera occupy a significant place. Theatre is by its nature multidisciplinary in the sense that it covers history, politics, performance, literature, society and other fields. Among other book-length studies published in the last few years, this art has yielded those with a historical perspective such as Joshua Goldstein‘s Drama Kings: Players and Publics in the Re-creation of Peking Opera, 1870–1937 (University of California Press, 2007) and those focusing more on stage aesthetics such as Alexandra B. Bonds‘ Beijing Opera Costumes: The Visual Communication of Character and Culture (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2008). -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography Note: This is a very selective list, with emphasis on recent Chinese publications. English titles are confi ned to those consulted by the author. Chinese titles are arranged alphabetically according to pinyin . The list is in seven parts: I. Bibliographies II. Periodicals III. Encyclopedias, dictionaries IV. Anthologies a. Comprehensive b. Fiction c. Poetry d. Drama e. Essays f. Miscellaneous V. General studies VI. Recent translations VII. Shakespeare studies I. Bibliographies ഭᇦࠪ⡸һъ㇑⨶ተ⡸ᵜമҖ侶㕆: 㘫䈁ࠪ⡸ཆഭਔި᮷ᆖ㪇ⴞᖅ 1949–1979, ѝॾҖተ, 1980 (Copyright Library, State Publishing Bureau, ed. Bibliography of Published Translations of Foreign Classics, 1949–1979) ѝഭ⽮Պ、ᆖ䲒ཆഭ᮷ᆖ⹄ウᡰ㕆: ᡁഭᣕ࠺ⲫ䖭Ⲵཆഭ᮷ᆖ૱઼䇴䇪᮷ㄐⴞᖅ㍒ᕅ (1978–1980), ेӜ, 1980 © Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing Co., Ltd 171 and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Z. Wang, Degrees of Affi nity, China Academic Library, DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-45475-6 172 Select Bibliography (Foreign Literature Research Institute, Academy of Social Sciences, ed. Bibliography of Foreign Literary Works and Critical Articles on them Published in Chinese Periodicals, 1978–1980) Deeney, John J. ed. Chinese English Comparative Literature Bibliography: A Pedagogical Arrangement of Sources in English, Tamkang Review , Vol, XII, No. 4 (Summer 1982) II. Periodicals (A, annual; 2/year, biannual; Q, quarterly; Bm, bimonthly; M, monthly; where names have changed, only present ones are given.) ᱕仾䈁ы (Spring Breeze Translation Miscellany) 2/year Shenyang 1980— ᖃԓ㣿㚄᮷ᆖ (Contemporary Soviet Literature) Bm -

The Politics of Celebrity in Madame Chiang Kai-Shek's

China’s Prima Donna: The Politics of Celebrity in Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s 1943 U.S. Tour By Dana Ter Columbia University |London School of Economics International and World History |Dual Master’s Dissertation May 1, 2013 | 14,999 words 1 Top: Madame Chiang speaking at a New Life Movement rally, taken by the author at Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall, Taipei, Taiwan, June 2012. Front cover: Left: Allene Talmey, “People and Ideas: May Ling Soong Chiang,” Vogue 101(8), (April 15, 1943), 34. Right: front page of the Kansas City Star, February 23, 1943, Stanford University Hoover Institution (SUHI), Henry S. Evans papers (HSE), scrapbook. 2 Introduction: It is the last day of March 1943 and the sun is beaming into the window of your humble apartment on Macy Street in Los Angeles’ “Old Chinatown”.1 The day had arrived, Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s debut in Southern California. You hurry outside and push your way through a sea of black haired-people, finding an opening just in time to catch a glimpse of China’s First Lady. There she was! In a sleek black cheongsam, with her hair pulled back in a bun, she smiled graciously as her limousine slid through the adoring crowd, en route to City Hall. The split second in which you saw her was enough because for the first time in your life you were proud to be Chinese in America.2 As the wife of the Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, from February-April 1943, Madame Chiang, also known by her maiden name, Soong Mayling, embarked on a carefully- crafted and well-publicized tour to rally American material and moral support for China’s war effort against the Japanese. -

Please Click Here to Download

No.1 October 2019 EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Tobias BIANCONE, GONG Baorong EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS (in alphabetical order by Pinyin of last name) Tobias BIANCONE, Georges BANU, Christian BIET, Marvin CARLSON, CHEN Jun, CHEN Shixiong, DING Luonan, Erika FISCHER-LICHTE, FU Qiumin, GONG Baorong, HE Chengzhou, HUANG Changyong, Hans-Georg KNOPP, HU Zhiyi, LI Ruru, LI Wei, LIU Qing, LIU Siyuan, Patrice PAVIS, Richard SCHECHNER, SHEN Lin, Kalina STEFANOVA, SUN Huizhu, WANG Yun, XIE Wei, YANG Yang, YE Changhai, YU Jianchun. EDITORS WU Aili, CHEN Zhongwen, CHEN Ying, CAI Yan CHINESE TO ENGLISH TRANSLATORS HE Xuehan, LAN Xiaolan, TANG Jia, TANG Yuanmei, YAN Puxi ENGLISH CORRECTORS LIANG Chaoqun, HUANG Guoqi, TONG Rongtian, XIONG Lingling,LIAN Youping PROOFREADERS ZHANG Qing, GUI Han DESIGNER SHAO Min CONTACT TA The Center Of International Theater Studies-S CAI Yan: [email protected] CHEN Ying: [email protected] CONTENTS I 1 No.1 CONTENTS October 2019 PREFACE 2 Empowering and Promoting Chinese Performing Arts Culture / TOBIAS BIANCONE 4 Let’s Bridge the Culture Divide with Theatre / GONG BAORONG STUDIES ON MEI LANFANG 8 On the Subjectivity of Theoretical Construction of Xiqu— Starting from Doubt on “Mei Lanfang’s Performing System” / CHEN SHIXIONG 18 The Worldwide Significance of Mei Lanfang’s Performing Art / ZOU YUANJIANG 31 Mei Lanfang, Cheng Yanqiu, Qi Rushan and Early Xiqu Directors / FU QIUMIN 46 Return to Silence at the Golden Age—Discussion on the Gains and Losses of Mei Lanfang’s Red Chamber / WANG YONGEN HISTORY AND ARTISTS OF XIQU 61 The Formation -

New Actresses and Urban Publics in Early Republican Beijing Title

Carnegie Mellon University MARIANNA BROWN DIETRICH COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements Doctor of Philosophy For the Degree of New Actresses and Urban Publics in Early Republican Beijing Title Jiacheng Liu Presented by History Accepted by the Department of Donald S. Sutton August 1, 2015 Readers (Director of Dissertation) Date Andrea Goldman August 1, 2015 Date Paul Eiss August 1, 2015 Date Approved by the Committee on Graduate Degrees Richard Scheines August 1, 2015 Dean Date NEW ACTRESSES AND URBAN PUBLICS OF EARLY REPUBLICAN BEIJING by JIACHENG LIU, B.A., M. A. DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the College of the Marianna Brown Dietrich College of Humanities and Social Sciences of Carnegie Mellon University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY CARNEGIE MELLON UNIVERSITY August 1, 2015 Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the help from many teachers, colleages and friends. First of all, I am immensely grateful to my doctoral advisor, Prof. Donald S. Sutton, for his patience, understanding, and encouragement. Over the six years, the numerous conversations with Prof. Sutton have been an unfailing source of inspiration. His broad vision across disciplines, exacting scholarship, and attention to details has shaped this study and the way I think about history. Despite obstacle of time and space, Prof. Andrea S. Goldman at UCLA has generously offered advice and encouragement, and helped to hone my arguments and clarify my assumptions. During my six-month visit at UCLA, I was deeply affected by her passion for scholarship and devotion to students, which I aspire to emulate in my future career. -

Report Title Paasch, Carl = Paasch, Karl Rudolf

Report Title - p. 1 of 545 Report Title Paasch, Carl = Paasch, Karl Rudolf (Minden 1848-1915 Zürich) : Deutscher Geschäftsmann, antisemitischer Publizist Bibliographie : Autor 1892 Paasch, Carl. Die Kaiserlich deutsche Gesandtschaft in China : eine Denkschrift über den Fall Carl Paasch für die dt. Landesvertretungen, insbesondere den Reichstag. (Leipzig : Im Selbstverlage des Verfassers, 1892). https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht?PPN=PPN610 163698&PHYSID=PHYS_0001&DMDID=. [Nachdem er sich bei Geschäften in China betrogen glaubte, verfasste Paasch eine Schrift, in welcher er die Beziehungen des deutschen Gesandten in China, Max von Brandt, zu Geschäftsleuten und Bankiers verurteilte. Theodor Fontane bezeichnete Paasch in einem Brief als Verrückten]. [Wik,WC] Paauw, Douglas S. = Paauw, Douglas Seymour (1921-) Bibliographie : Autor 1951 Bibliography of modern China : works in Western languages (revised) : section 5, economic. Compiled by Douglas S. Paauw and John K. Fairbank for the Regional Studies Program on China. (Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University, 1951). Pabel, Hilmar (1910-2000) : Photojournalist Bibliographie : Autor 1986 Pabel, Romy ; Pabel, Hilmar. Auf Marco Polos Spuren : Expedition Seidenstrasse. (München : Süddeutscher Verlag, 1986). [Bericht ihrer Reise 1985, Shanghai, Xi'an, Lanzhou, Jiayuguan, Grosse Mauer, Dunhuang, Ruoqiang, Qiemo, Minfeng, Hotan, Yecheng, Yarkant, Kaxgar, Indien]. [Cla] Pabel, Romy (um 1985) : Gattin von Hilmar Pabel Bibliographie : Autor 1986 Pabel, Romy ; Pabel, Hilmar. Auf Marco Polos Spuren : Expedition Seidenstrasse. (München : Süddeutscher Verlag, 1986). [Bericht ihrer Reise 1985, Shanghai, Xi'an, Lanzhou, Jiayuguan, Grosse Mauer, Dunhuang, Ruoqiang, Qiemo, Minfeng, Hotan, Yecheng, Yarkant, Kaxgar, Indien]. [Cla] Pabst, Georg Wilhelm (Raudnitz, Böhmen 1885-1967 Wien) : Österreichischer Filmregisseur Biographie 1938 Le drame de Shanghai. Un film de G.W. Pabst ; d'après l'oeuvre de O.P. -

Anna May Wong

Anna May Wong From Laundryman’s Daughter to Hollywood Legend Graham Russell Gao Hodges Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2012 Copyright © 2004 by Graham Russell Gao Hodges First published by Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-988-8139-63-7 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Liang Yu Printing Factory Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Preface to Second Edition ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction xv List of Illustrations xxiii One Childhood 1 Two Seeking Stardom 27 Three Europe 65 Four Atlantic Crossings 99 Five China 141 Six In the Service of the Motherland 159 Seven Becoming Chinese American 191 Epilogue 207 Filmography 213 Television Appearances 223 Notes 225 Selected Bibliography 251 Index 265 Introduction Anna May Wong (1905–1961) remains the premier Asian American actress. In part this distinction stems from the historical rarity of Asian actors in American cinema and theater, yet her singularity derives primarily from her laudable acting in more than fifty movies, during a career that ranged from 1919 to 1961, a record of achievement that is unmatched and likely to remain so in the foreseeable future. -

The Market, Ideology, and Convention Jingju Performers’ Creativity in the 21St Century Li Ruru

The Market, Ideology, and Convention Jingju Performers’ Creativity in the 21st Century Li Ruru Driven by the imperatives of a changing society and the pressures of new technology, China’s theatre is undergoing continual transformation, both in its performance and understanding by practitioners and in its reception by audiences. Jingju (known in the West as Beijing Opera) — a highly stylized theatrical genre founded on specific role types and spectacular stage conven- tions — is no exception to this process. As new media devices and possibilities appear at an unprecedented pace, these developments afford artists tremendous choices and fundamentally alter not only what constitutes theatre but also the mentality of practitioners and spectators. Since the nadir of the Cultural Revolution, a more than tenfold increase in gross domestic product has made China a powerful voice in the global capitalist community and a generous benefactor of its theatre. The budget for starting a stage show can now easily reach around five million RMB (about US$800,000). “Forging exquisite productions” (dazao jingpin) to obtain Figure 1. Ailiya (Shi Yihong) dances for her beggar friends. Shanghai, 2008. (Courtesy of the Shanghai Jingju Theatre) TDR: The Drama Review 56:2 (T214) Summer 2012. ©2012 New York University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology 131 Downloaded from http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/DRAM_a_00171 by guest on 28 September 2021 national prizes seems to be the ultimate objective of all theatre companies and local authorities, so the funding enables theatre, including jingju, to do things that it could not have dreamed of 30 years ago. -

The Case of Theater Illustrated (1912-17)

East Asian History NUMBER 28 . DECEMBER 2004 Instit ute of Adva nced St ud ies Australia n Na ti onal Uni ve rsity Ed ito r Ge re mie R. Ba rm e Associate Ed ito r Mi riam Lang Business Manage r Ma ri on We eks Edito ri al Boa rd B 0rg e Bakken Jo hn Cl ark Louise Ed wa rds Ma rk Elvin (Con veno r) Jo hn Fi tzge ra ld Co li n Je ffcot t Li Tana Kam Louie Lewis Mayo Ga va n Mc Cormack Da vid Ma rr Tessa Mo rris-Suzuki Benjamin Penny Kenneth We lls Design and Production Oanh Co llins, Ma rion We eks, Max ine McA rthu r, Tristan No rman Printed by Go anna Prin t, Fyshwick, ACT This is the tw en ty-e ig hth is s ue of East Asian History, prin ted in Decembe r 2005, in the se ries pre vi o us ly entit le d Papers on Far Eastern History. Th is ex te rn ally re fe re ed journa l is pub li shed twi ce a ye ar Co nt rib utions to The Ed it or, East Asian History Division of Pacific and Asian Histo ry Resea rch Sc hoo l of Pacific and Asian St udies Aust ralian Na ti onal Uni versi ty Ca nbe rra ACT 0200, Aust ralia Phone +6 1 26125 3140 Fax +6 1 26125 5525 Em ailma rion.weeks @anu.ed u.au Su bsc ri pt ion En quiries to Su bsc riptions, East Asian History, at the abo ve add ress, orto ma rion.weeks @an u. -

Table of Contents and Contributors

Contents List of Entries viii List of Contributors ix Introduction and Acknowledgments xxx Joan Lebold Cohen xxxviii Volume 1 Abacus to Cult of Maitreya Volume 2 Cultural Revolution to HU Yaobang Volume 3 Huai River to Old Prose Movement Volume 4 Olympics Games of 2008 to TANG Yin Volume 5 Tangshan Earthquake, Great to ZUO Zongtang Image Sources Volume 5, page 2666 Index Volume 5, page 2667 © 2009 by Berkshire Publishing Group LLC List of Entries Abacus Asian Games BORODIN, Mikhail Academia Sinica Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Boxer Protocol (Xinchou Treaty) Acrobatics Atheism Boxer Rebellion Acupuncture Australia China Friendship Society Boycotts and Economic Adoption Australia-China Relations Nationalism Africa-China Relations Auto Industry BRIDGMAN, E. C. Agricultural Cooperatives Autonomous Areas British American Tobacco Movement BA Jin Company Agriculture Bamboo British Association for Chinese Agro-geography Bank of China Studies American Chamber of Commerce Banking—History British Chamber of Commerce in in China Banking—Modern China Ami Harvest Festival Banque de l’Indochine Bronzes of the Shang Dynasty An Lushan (An Shi) Rebellion Baojia Brookings Institution Analects Baosteel Group Buddhism Ancestor Worship Beijing Buddhism, Chan Anhui Province Beijing Consensus Buddhism, Four Sacred Sites of Antidrug Campaigns Bian Que Buddhism, Persecution of Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign Bianzhong Buddhism, Pure Land Anyang Bishu Shanzhuang Buddhism, Tibetan Aquaculture Black Gold Politics Buddhist Association of China Archaeology and -

"Experimenting with Dance Drama: Peking Opera Modernity, Kabuki Theater Reform and the Denishawn’S Tour of the Far East"

Journal of Global Theatre History ISSN: 2509-6990 Issue 1, Number 2, 2016, pp. 28-37 Catherine Vance Yeh "Experimenting with Dance Drama: Peking Opera Modernity, Kabuki Theater Reform and the Denishawn’s Tour of the Far East" Abstract During the 1910s and 20s, Peking opera underwent a fundamental transformation from a performing art primarily driven by singing to one included acting and dancing. Leading this new development were male actors playing female roles, with Mei Lanfang as the most outstanding example. The acknowledged sources on which these changes drew were the encounter with Western style opera. The artistic and social values carrying these changes, however, suggest that Peking opera underwent a qualitative reconceptualization that involved a critical break with its past. This paper will explore the artistic transformation of Peking opera of the 1910s-20s by focusing on the three areas of contact Paris, Japan and the US. It will argue that the particular artistic innovation in Peking can only be fully understood and appraised in the context of global cultural interaction. It suggests that a new assessment of the modernist movement is needed that sees it as a part of a global trend rather than only as a European phenomenon. Author Catherine Vance Yeh is Professor of Modern Chinese Literature and Transcultural Studies at Boston University. Her research focuses on the global migration of literary forms; the transformation of theater aesthetics in transcultural interaction, and entertainment culture as agent of social change. Her publications include Shanghai Love: Courtesans, Intellectuals and Entertainment Culture, 1850-1910; and The Chinese Political Novel: Migration of a World Genre.