Asepsis and Bacteriology: a Realignment of Surgery and Laboratory Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 Oil Painting by American Artist Thomas Eakins

Antisepsis and women in surgery 12 The Gross ClinicThe, byPharos Thomas/Winter Eakins, 2019 1875. Photo by Geoffrey Clements/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images The Agnew Clinic, an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty images Don K. Nakayama, MD, MBA Dr. Nakayama (AΩA, University of California, San Francisco, Los Angeles, 1986, Alumnus), emeritus professor of history 1977) is Professor, Department of Surgery, University of of medicine at Johns Hopkins, referring to Joseph Lister North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC. (1827–1912), pioneer in the use of antiseptics in surgery. The interpretation fits so well that each surgeon risks he Gross Clinic (1875) and The Agnew Clinic (1889) being consigned to a period of surgery to which neither by Thomas Eakins (1844–1916) face each other in belongs; Samuel D. Gross (1805–1884), to the dark age of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, in a hall large surgery, patients screaming during operations performed TenoughT to accommodate the immense canvases. The sub- without anesthesia, and suffering slow, agonizing deaths dued lighting in the room emphasizes Eakins’s dramatic use from hospital gangrene, and D. Hayes Agnew (1818–1892), of light. The dark background and black frock coats worn by to the modern era of aseptic surgery. In truth, Gross the doctors in The Gross Clinic emphasize the illuminated was an innovator on the vanguard of surgical practice. head and blood-covered fingers of the surgeon, and a bleed- Agnew, as lead consultant in the care of President James ing gash in pale flesh, barely recognizable as a human thigh. -

Cardiac Surgery

Gerhard Ziemer Axel Haverich Editors Cardiac Surgery Operations on the Heart and Great Vessels in Adults and Children 123 Cardiac Surgery Gerhard Ziemer Axel Haverich Editors Cardiac Surgery Operations on the Heart and Great Vessels in Adults and Children Editors Gerhard Ziemer Axel Haverich Department of Surgery HTTG - Surgery The University of Chicago Medizinische Hochschule Hannover Chicago, IL Hannover USA Germany ISBN 978-3-662-52670-5 ISBN 978-3-662-52672-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-662-52672-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939170 © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2017 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Department of General Surgery Medical Academy Named After S.I

Department of General Surgery Medical Academy named after S.I. Georgievskiy, The Federal State Autonomous Educational Establishment of Higher Education “Crimean Federal University named after V.I. Vernadsky” Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation For the 3rd year students The text of the lectures and the minimum amount of knowledge necessary for a understanding of the subject material. Topic: Aseptics & Antiseptics in surgery Authors: prof.Mikhailychenko V.Yu, Starykh A.A. 2015 Aseptics & Antiseptics in surgery History of aseptic and antiseptic Empirical asepsis In ancient times, demons and evil spirits were though to be the causes of pestilence and infections. Hippocrates (460-377 BC), the great healer of his time irrigated wounds with wine or boiled water foreshadowing asepsis. Galen (130-200 A.D.), a Greek that practiced medicine in Rome and was the most distinguished physician after Hippocrates boiled his surgical instruments used in the caring of wounded gladiators. The writing of Hippocrates and Galen were the established authority for many centuries. In the early to mid 1800's, people like Ignaz Semmelweis, Louis Pasteur, and Robert Koch introduced us to the world of microorganisms. Since this time, we have witnessed the invention of the first steam sterilizer (1886), the practice of passive and active immunization, and the use of antibiotics. Today, we practice asepsis and sterile technique based on scientific principles. Infection control, asepsis, body substance, and sterile technique should always be a part of patient care at any level. Joseph Lister (5 April 1827 — 10 February 1912) was a Scottish surgeon who picked up the work of Louis Pasteur and used it to change the success rates of surgery. -

Bundeswehr-Standortbroschüre München

Inhaltsverzeichnis Grußwort des Standortältesten von München 2 Grußwort des Oberbürgermeisters von München 3 Die Bayern-Kaserne 7 Die Fürst-Wrede-Kaserne 12 Feldjägerbataillon 451 12 Kraftfahrausbildungszentrum München 13 Regionales Netzführungszentrum 60 14 Festes Fernmeldezentrum der Bundeswehr 663/900 14 Das Sanitätsamt der Bundeswehr 15 Die Ernst-von-Bergmann-Kaserne 17 Das Zentrale Institut des Sanitätsdienstes der Bundeswehr München 19 Universität der Bundeswehr München 21 Pionierschule und Fachschule des Heeres für Bautechnik 24 Wehrbereichsverwaltung Süd – Außenstelle München 25 Bundeswehrdienstleistungszentrum München 26 Kreiswehrersatzamt München 26 Truppendienstgericht Süd 27 Infrastrukturstab SÜD – Außenstelle München, Dezernat 3 28 Bundessprachenamt Referat SMD 9 28 Zentrum für Transformation (Tle Ottobrunn) 29 Systemunterstützungszentrum NH 90/TIGER 30 Güteprüfstelle der Bundeswehr München 31 Freizeitbüro Standort München 31 Standortübungsplatz „Fröttmaninger Heide“ 32 Branchenverzeichnis 5 Impressum 5 1 Grußwort des Standortältesten von München Als Standortältester der Landeshauptstadt Bayerns – München – begrüße ich Sie sehr herzlich. Sie sind zu Gast in unserem Standort München oder als Soldatin, Soldat, zivile Mitarbeiterin oder Mitarbeiter der Bundeswehr in die Landeshauptstadt Bayerns versetzt worden. Damit sind Sie nunmehr an einem der schönsten und attrak- tivsten Standorte der Bundeswehr eingesetzt. Trotz der Auflösung verschiedener Verbände und Dienststellen ist München nach wie vor eine der größten Standorte unserer Streitkräfte mit mehreren wichtigen und hochwertigen Dienst- stellen und Einrichtungen der Bundeswehr. So sind das Wehrbereichskommando IV, die Wehrbereichsver- waltung Süd mit ihrer Außenstelle München, das Sanitätsamt der Bundeswehr, die Sanitätsakademie der Bundeswehr, die Bundeswehruniversität München, die Pionierschule der Bundes- wehr, das Feldjägerbataillon 451, das Zentrale Institut des Sa- nitätsdienstes der Bundeswehr, das Landeskommando Bayern, das seit dem 1. Januar d.J. -

Nobel Prize Commemoration in Riga: Media Echo and Objects

Acta medico-historica Rigensia (2018) XI: 92-120 doi:10.25143/amhr.2018.XI.03 Juris Salaks, Nils Hansson Nobel Prize Commemoration in Riga: Media Echo and Objects Abstract This paper is an attempt to investigate the discourses around the Nobel Prize, and it aims at deciphering the commemoration of the award in Riga. The public image of the Nobel Prize in Riga has previously been commented on in a few papers, but has never been studied at length. The first part of the current study contextualises several Nobel links from the city, universi- ties and state printed media, as well as more hidden tracks from the Nobel Prize nominations’ archive. The second part highlights Ilya Mechnikov (Elie Metchnikoff’s, Nobel laureate in physiology or medicine in 1908) collection in Pauls Stradins Museum of the History of Medicine, including a detailed description of his Nobel medal and his ambivalent feelings about this award. Keywords: Nobel Prize, Latvian press, Riga, Baltic States, Ilya Mechnikov (Elie Metchnikoff), Paul Ehrlich, Wilhelm Ostwald, Paul Valden, Ernst von Bergmann, Harald zur Hausen. Several compendia on the history of medicine use the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine as a lens for reviewing scientific trends in the history of medicine in the last century. The medical historian Erwin Ackerknecht, for instance, argued that the tendencies of the 20th century cutting-edge medicine are illustrated by the names of those who received the Nobel Prize. 1 1 Erwin H. Ackerknecht, A short history of medicine (New York: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1968). 92 Also, more recent textbooks, such as Ortrun Riha’s Grundwissen Geschichte, Theorie und Ethik der Medizin 2, Jacalyn Duffin’s History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction 3, Tatiana Sorokina’s History of Medicine 4 have (at least in some editions) enclosed lists of Nobel laureates to highlight prominent work throughout the 20th century. -

Neurology and Neurologists During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871)

Neurologists during Wars Tatu L, Bogousslavsky J (eds): War Neurology. Front Neurol Neurosci. Basel, Karger, 2016, vol 38, pp 77–92 (DOI: 10.1159/000442595) Neurology and Neurologists during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) Olivier Walusinski Family Physician, Brou , France Abstract ‘All those whose spinal cord or brain The Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) ended with the had been reached by bullets firm establishment of the French Republic and with Ger- were like corpses, in a deathlike coma.’ man unity under Prussian leadership. After describing the Emile Zola (1840–1902) [1] events leading to the war, we explain how this conflict was the first involving the use of machine guns; soldiers were struck down by the thousands. Confronted with To Let Loose the Dogs of War smallpox and typhus epidemics, military surgeons were quickly overwhelmed and gave priority to limb injuries, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) in considering other wounds as inevitably fatal. Here, we Prussia and Emperor Napoleon III (1808–1873) present detailed descriptions of spinal and cranial injuries in France each desired a war, as much to resolve by Léon Legouest and of asepsis prior to trepanning internal political difficulties as to ensure their su- by Ernst von Bergmann. Both the war and the Commune premacy in Europe. Prussia, which had just won had disastrous effects on Paris. Jean-Martin Charcot con- the war against Austria at Sadowa (3 July 1866), tinued to work intensely through the conflict, caring for initially benefitted from a certain degree of ac- numerous patients at La Salpêtrière Hospital according commodation by Napoleon III, allowing Bis- to his son Jean-Baptiste’s account, which we’ve also ex- marck to attempt to unify the German states cerpted below. -

Sterilisation

ZENTRAL D 2596 F 2010 Avril Année/Año 18 RSevue inTternatiEonale RILISATRevisIta inOternacionaNl c oncernant la stérilisation Suppl.1 sobre la esterilización Technique : état des lieux – Concepts pour l’avenir FORUM International Dispositifs Estado de la técnica: Médicaux et Procédures Conceptos para el futuro Vérification des paramè- tres des performances FORUM Internacional de Productos Verificación de los pará- metros de rendimiento Médicos y Procedimientos Qu’est-ce que nous pou- vons à vrai dire certifier ? ¿Qué es lo que se puede realmente certificar? Qu’est-ce qui est néces- saire, qu’est-ce qui est possible ? ¿Qué se necesita? ¿Qué es Le meilleur sur une posible? période de 10 ans Gestion des instruments Gestión del instrumental Lo mejor de los Réglementation des últimos 10 años unités des stérilisation : Prétentions et contra- dictions Sistema de regulación CEYE: Aspiraciones y contradicciones Prévention Prevención Contrôle des processus Controles en proceso Utilisateurs et experts Usuarios y expertos Retraitement – Prière de rester simple ! ¡Reprocesamiento, pero por favor sencillo! 0_Titel_ZT_Suppl1_10.indd 1 21.04.10 19:17 U2_Forumseite 21.04.2010 13:12 Uhr Seite 1 Prof. Dr. Peter Heeg Rédacteur en chef EDITORIAL Redactor jefe FORUM International Dispositifs Médicaux et Procédés : Le meilleur sur une période de 10 ans ! FORO Internacional Productos Médicos y Procedemientos : ¡Lo mejor de los últimos 10 años! es 10 dernières années ont apporté non seulement une nouvelle n estos diez últimos años hemos asistido no sólo a una nueva di- Lfaçon de voir le retraitement des dispositifs médicaux orienté Emensión del reprocesamiento de los productos sanitarios orientada vers les processus de retraitement, mais ont également permis, grâce al proceso, sino también a numerosos pasos para mejorar nuestros à de nombreux petits pas, l’acquisition de nouvelles connaissances, conocimientos, las estructuras y la seguridad de los pacientes. -

FORUM Panamericano Dispositos Medicos Procesos Relacionados

Fifth edition ● Quinta edición FORUM PanAmericano 5 Dispositivos Médicos y Procesos Relacionados – desde 2016 International FORUM Medical Devices & Processes since 1999 ¿Estéril, pero no limpio? Sterile, but not clean? www.mhp-medien.de Investigation & Application Investigación & Aplicación VISUALLY INSPECT WITH REMARKABLE CLARITY The FIS includes a distal �p composed of a light source and camera lens at the end of a 110cm flexible sha�, which features gradua�on marks. The Flexible Inspec�on Scope is a perfect tool to get a visualiza�on of any poten�ally soiled device. So�ware is included and allows viewing and recording. FIS-005SK 110CM LONG 2.0MM DIAMETER FIS-006SK 110CM LONG 1.3MM DIAMETER HEALTHMARK OFFERS MANY OPTICAL INSPECTION TOOLS TO SUIT YOUR NEEDS MAGIC TOUCH HANDHELD MADE IN AMERICA 4X LED MAGNIFIER MULTI-MAGNIFIER MAGNIFIER MAGNIFIER HEALTHMARK INDUSTRIES CO. | HMARK.COM | 800.521.6224 | [email protected] FORUM PanAmericano 1/2020 1 Editorial Sterile but not clean: Florence Nightingale searched for evidence Estéril, pero no limpio: Florence Nightingale buscada la «evidencia» a esterilización se remonta a la obra de Louis Pasteur y también a la terilization is attributed to the discoveries of Louis Pasteur but credit Lde Florence Nightingale, una mujer británica nacida en la Toscana y Sfor this is also often given to the British nurse, Florence Nightingale, formada en un hospital alemán cerca de Düsseldorf (Kaiserswerth who was born in Tuscany, trained among other places at a German 1850/51) que trabajó para el imperio colonial británico en el siglo XIX. A hospital in Düsseldorf (Kaiserswerth 1850/51), and worked in the service través de sus viajes y de su experiencia posterior en la Guerra de Crimea of the British Empire during the 19th century. -

Dissertationes Historiae Universitatis Tartuensis 14

DISSERTATIONES HISTORIAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 14 DISSERTATIONES HISTORIAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 14 ERAALGATUSLIKEST STIPENDIUMIDEST TARTU ÜLIKOOLIS 1802–1918 SIRJE TAMUL Tartu Ülikooli Ajaloo ja Arheoloogia Instituut, Tartu, Eesti Kaitsmisele lubatud Tartu Ülikooli filosoofiateaduskonna ajaloo ja arheoloogia instituudi nõukogu doktoritööde kaitsmise komisjoni otsusega 27. augustist 2007. Teaduslik juhendaja: dotsent PhD (ajalugu) Tõnu-Andrus Tannberg Oponent: PhD (geograafia) Erki Tammiksaar (Eesti Maaülikool) Kaitsmine toimub 27. septembril 2007 kell 16.15 Tartu Ülikooli Nõukogu saalis Ülikooli 18. Töö on valminud Eesti Vabariigi Haridus- ja Teadusministeeriumi sihtfinant- seeringu DFLAJ 2220 ja SF 0182700s05 toetusel. ISSN 1406–443X ISBN 978–9949–11–701–7 (trükis) ISBN 978–9949–11–702–4 (PDF) Autoriõigus Sirje Tamul, 2007 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus www.tyk.ee Tellimus nr 337 SISUKORD SISSEJUHATUS............................................................................................ 9 1. Uurimisülesanne ja põhimõisted .......................................................... 9 2. Metoodikast.......................................................................................... 14 3. Historiograafia...................................................................................... 15 4. Allikad.................................................................................................. 21 ESIMENE OSA.............................................................................................. 25 I. Peatükk. Ajalooline -

Chapter 4 'Now, Back to Our Virchow': German Medical and Political

21-4-2020 ‘Now, back to our Virchow’: German Medical and Political Traditions in Post-war Berlin - The Perils of Peace - NCBI Bookshelf NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Reinisch J. The Perils of Peace: The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany. Oxford (UK): OUP Oxford; 2013 Jun 6. Chapter 4 ‘Now, back to our Virchow’:1 German Medical and Political Traditions in Post-war Berlin In these current dark times there are still some rays of light for the German people—in spite of all errors and crimes which have been perpetrated in their name—they are the rays of hope which arise from the unquenchable spring of their intellectual and spiritual past.2 As they arrived in Germany, the Allies were forced to rely on the cooperation of the German medical authorities. While Chapter 3 looked at German émigrés, this chapter focuses on those German doctors and health officers who never left the country, the large majority in the profession. How did they reflect on the events of the previous decade? How did they present their careers and relate to their émigré compatriots, some of whom were now returning to Germany, and the occupiers? This chapter focuses on Berlin, which became both the seat of the quadripartite Allied Control Council (ACC) and the capital of the Soviet zone. Most historians have now abandoned the once-popular idea of a ‘Zero Hour’ (Stunde Null) and a radical transformation of German society after the end of the war. This chapter, too, shows that the break after 1945 was not nearly as radical as many earlier studies claimed. -

THE Centenary of the Foundation of the Operateurinstitute

981 and even eagerly. The State is now appealed to on the of( the nodules resembling testicles. The family history was score of economy, so as to cheapen the bon-bons down to theunimportanti except that the grandfathers of the parents purchasing power of the very poor ; and it is confidentlywere brothers. The father of the girls asked to have the expected that its response will be such as to leave no ttwo testicles of the younger girl removed, whilst the elder commune, however indigent, without access to a remedygirli suffered from time to time from pains in her testicle, so efficacious beyond all others in combating the national thatt the question arose whether this operation, which might scourge. be1 called castration, was justified. The existence of these March 30th. malformations rise to some ___________________ naturally gave difficulty inthe selection of an occupation for the girls. VIENNA. Ulceration of the Skin after Diagnostic Application of the X Rays. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) It is not often that a single cautious application of the - x rays for the purpose of ascertaining the presence of metallic Centenary of the Operateurinstitute, objectsc in the human body leads to grave consequences. Such a was shown Professor at the same THE of the foundation of the case, however, by Lang centenary Operateurinstitutemeeting of the Gesellschaft der Aerzte. The patient was or school for in which was established surgeons Vienna, by a man who had been of swallowed several the Francis I. on the of Dr. was suspected having Emperor suggestion Kern, nails when in a condition. -

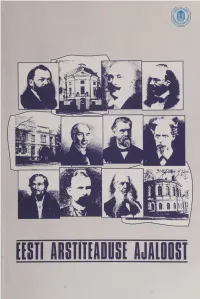

Eesti Arstiteaduse Uiioosi

EESTI ARSTITEADUSE UIIOOSI [tüll ШПТЕШИ Ш Ш 1 Koostanud Viktor Kalnin TARTU ÜLDCDOLI KIRJASTUS Kaane kujundanud Lemmi Koni Korrektor Leelo Jago ©Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 1996 ISBN 9985-56-148-1 Sisu trükk: AS Levileht Fotod, kaas ja köide: Tkrtu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tellimus nr. 138 SISUKORD Peter Ernst Wilde (1732-1785). Viktor Kalnin ............................................. 7 Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Luce (1750-1842). Boriss Schamardin, Viktor Kalnin. 12 Martin Ernst Styx (1759-1829). Viktor Kalnin................................................. 16 Karl Espenberg (1761-1822). Heino Gustavson................................................. 20 Daniel Georg Balk (1764-1826). Viktor Kalnin................................................. 25 Christian Friedrich von Deutch (1768-1843). Viktor Kalnin.......................... 30 David Hieronymus Grindel (1776-1836). Viktor Kalnin................................... 34 Karl Friedrich Burdach (1776-1847). Viktor Kalnin, Ela Lepp........................ 38 Johann Friedrich von Erdmann (1778-1846). Kuno Kõrge............................ 42 Karl Ernst von Baer (1792-1876). Maie Remmel............................................. 47 Friedrich Robert Faehlmann (1798-1850). Viktor Kalnin................................ 51 Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803-1882). Viktor Kalnin .......................... 57 Philipp Jakob Karell (1806-1886). Viktor Kalnin............................................. 63 Friedrich Bidder (1810-1894). Viktor Kalnin ..................................................