Fixed and Dilated: the History of a Classic Pupil Abnormality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bundeswehr-Standortbroschüre München

Inhaltsverzeichnis Grußwort des Standortältesten von München 2 Grußwort des Oberbürgermeisters von München 3 Die Bayern-Kaserne 7 Die Fürst-Wrede-Kaserne 12 Feldjägerbataillon 451 12 Kraftfahrausbildungszentrum München 13 Regionales Netzführungszentrum 60 14 Festes Fernmeldezentrum der Bundeswehr 663/900 14 Das Sanitätsamt der Bundeswehr 15 Die Ernst-von-Bergmann-Kaserne 17 Das Zentrale Institut des Sanitätsdienstes der Bundeswehr München 19 Universität der Bundeswehr München 21 Pionierschule und Fachschule des Heeres für Bautechnik 24 Wehrbereichsverwaltung Süd – Außenstelle München 25 Bundeswehrdienstleistungszentrum München 26 Kreiswehrersatzamt München 26 Truppendienstgericht Süd 27 Infrastrukturstab SÜD – Außenstelle München, Dezernat 3 28 Bundessprachenamt Referat SMD 9 28 Zentrum für Transformation (Tle Ottobrunn) 29 Systemunterstützungszentrum NH 90/TIGER 30 Güteprüfstelle der Bundeswehr München 31 Freizeitbüro Standort München 31 Standortübungsplatz „Fröttmaninger Heide“ 32 Branchenverzeichnis 5 Impressum 5 1 Grußwort des Standortältesten von München Als Standortältester der Landeshauptstadt Bayerns – München – begrüße ich Sie sehr herzlich. Sie sind zu Gast in unserem Standort München oder als Soldatin, Soldat, zivile Mitarbeiterin oder Mitarbeiter der Bundeswehr in die Landeshauptstadt Bayerns versetzt worden. Damit sind Sie nunmehr an einem der schönsten und attrak- tivsten Standorte der Bundeswehr eingesetzt. Trotz der Auflösung verschiedener Verbände und Dienststellen ist München nach wie vor eine der größten Standorte unserer Streitkräfte mit mehreren wichtigen und hochwertigen Dienst- stellen und Einrichtungen der Bundeswehr. So sind das Wehrbereichskommando IV, die Wehrbereichsver- waltung Süd mit ihrer Außenstelle München, das Sanitätsamt der Bundeswehr, die Sanitätsakademie der Bundeswehr, die Bundeswehruniversität München, die Pionierschule der Bundes- wehr, das Feldjägerbataillon 451, das Zentrale Institut des Sa- nitätsdienstes der Bundeswehr, das Landeskommando Bayern, das seit dem 1. Januar d.J. -

Nobel Prize Commemoration in Riga: Media Echo and Objects

Acta medico-historica Rigensia (2018) XI: 92-120 doi:10.25143/amhr.2018.XI.03 Juris Salaks, Nils Hansson Nobel Prize Commemoration in Riga: Media Echo and Objects Abstract This paper is an attempt to investigate the discourses around the Nobel Prize, and it aims at deciphering the commemoration of the award in Riga. The public image of the Nobel Prize in Riga has previously been commented on in a few papers, but has never been studied at length. The first part of the current study contextualises several Nobel links from the city, universi- ties and state printed media, as well as more hidden tracks from the Nobel Prize nominations’ archive. The second part highlights Ilya Mechnikov (Elie Metchnikoff’s, Nobel laureate in physiology or medicine in 1908) collection in Pauls Stradins Museum of the History of Medicine, including a detailed description of his Nobel medal and his ambivalent feelings about this award. Keywords: Nobel Prize, Latvian press, Riga, Baltic States, Ilya Mechnikov (Elie Metchnikoff), Paul Ehrlich, Wilhelm Ostwald, Paul Valden, Ernst von Bergmann, Harald zur Hausen. Several compendia on the history of medicine use the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine as a lens for reviewing scientific trends in the history of medicine in the last century. The medical historian Erwin Ackerknecht, for instance, argued that the tendencies of the 20th century cutting-edge medicine are illustrated by the names of those who received the Nobel Prize. 1 1 Erwin H. Ackerknecht, A short history of medicine (New York: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1968). 92 Also, more recent textbooks, such as Ortrun Riha’s Grundwissen Geschichte, Theorie und Ethik der Medizin 2, Jacalyn Duffin’s History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction 3, Tatiana Sorokina’s History of Medicine 4 have (at least in some editions) enclosed lists of Nobel laureates to highlight prominent work throughout the 20th century. -

Neurology and Neurologists During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871)

Neurologists during Wars Tatu L, Bogousslavsky J (eds): War Neurology. Front Neurol Neurosci. Basel, Karger, 2016, vol 38, pp 77–92 (DOI: 10.1159/000442595) Neurology and Neurologists during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) Olivier Walusinski Family Physician, Brou , France Abstract ‘All those whose spinal cord or brain The Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) ended with the had been reached by bullets firm establishment of the French Republic and with Ger- were like corpses, in a deathlike coma.’ man unity under Prussian leadership. After describing the Emile Zola (1840–1902) [1] events leading to the war, we explain how this conflict was the first involving the use of machine guns; soldiers were struck down by the thousands. Confronted with To Let Loose the Dogs of War smallpox and typhus epidemics, military surgeons were quickly overwhelmed and gave priority to limb injuries, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898) in considering other wounds as inevitably fatal. Here, we Prussia and Emperor Napoleon III (1808–1873) present detailed descriptions of spinal and cranial injuries in France each desired a war, as much to resolve by Léon Legouest and of asepsis prior to trepanning internal political difficulties as to ensure their su- by Ernst von Bergmann. Both the war and the Commune premacy in Europe. Prussia, which had just won had disastrous effects on Paris. Jean-Martin Charcot con- the war against Austria at Sadowa (3 July 1866), tinued to work intensely through the conflict, caring for initially benefitted from a certain degree of ac- numerous patients at La Salpêtrière Hospital according commodation by Napoleon III, allowing Bis- to his son Jean-Baptiste’s account, which we’ve also ex- marck to attempt to unify the German states cerpted below. -

Dissertationes Historiae Universitatis Tartuensis 14

DISSERTATIONES HISTORIAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 14 DISSERTATIONES HISTORIAE UNIVERSITATIS TARTUENSIS 14 ERAALGATUSLIKEST STIPENDIUMIDEST TARTU ÜLIKOOLIS 1802–1918 SIRJE TAMUL Tartu Ülikooli Ajaloo ja Arheoloogia Instituut, Tartu, Eesti Kaitsmisele lubatud Tartu Ülikooli filosoofiateaduskonna ajaloo ja arheoloogia instituudi nõukogu doktoritööde kaitsmise komisjoni otsusega 27. augustist 2007. Teaduslik juhendaja: dotsent PhD (ajalugu) Tõnu-Andrus Tannberg Oponent: PhD (geograafia) Erki Tammiksaar (Eesti Maaülikool) Kaitsmine toimub 27. septembril 2007 kell 16.15 Tartu Ülikooli Nõukogu saalis Ülikooli 18. Töö on valminud Eesti Vabariigi Haridus- ja Teadusministeeriumi sihtfinant- seeringu DFLAJ 2220 ja SF 0182700s05 toetusel. ISSN 1406–443X ISBN 978–9949–11–701–7 (trükis) ISBN 978–9949–11–702–4 (PDF) Autoriõigus Sirje Tamul, 2007 Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus www.tyk.ee Tellimus nr 337 SISUKORD SISSEJUHATUS............................................................................................ 9 1. Uurimisülesanne ja põhimõisted .......................................................... 9 2. Metoodikast.......................................................................................... 14 3. Historiograafia...................................................................................... 15 4. Allikad.................................................................................................. 21 ESIMENE OSA.............................................................................................. 25 I. Peatükk. Ajalooline -

Chapter 4 'Now, Back to Our Virchow': German Medical and Political

21-4-2020 ‘Now, back to our Virchow’: German Medical and Political Traditions in Post-war Berlin - The Perils of Peace - NCBI Bookshelf NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Reinisch J. The Perils of Peace: The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany. Oxford (UK): OUP Oxford; 2013 Jun 6. Chapter 4 ‘Now, back to our Virchow’:1 German Medical and Political Traditions in Post-war Berlin In these current dark times there are still some rays of light for the German people—in spite of all errors and crimes which have been perpetrated in their name—they are the rays of hope which arise from the unquenchable spring of their intellectual and spiritual past.2 As they arrived in Germany, the Allies were forced to rely on the cooperation of the German medical authorities. While Chapter 3 looked at German émigrés, this chapter focuses on those German doctors and health officers who never left the country, the large majority in the profession. How did they reflect on the events of the previous decade? How did they present their careers and relate to their émigré compatriots, some of whom were now returning to Germany, and the occupiers? This chapter focuses on Berlin, which became both the seat of the quadripartite Allied Control Council (ACC) and the capital of the Soviet zone. Most historians have now abandoned the once-popular idea of a ‘Zero Hour’ (Stunde Null) and a radical transformation of German society after the end of the war. This chapter, too, shows that the break after 1945 was not nearly as radical as many earlier studies claimed. -

THE Centenary of the Foundation of the Operateurinstitute

981 and even eagerly. The State is now appealed to on the of( the nodules resembling testicles. The family history was score of economy, so as to cheapen the bon-bons down to theunimportanti except that the grandfathers of the parents purchasing power of the very poor ; and it is confidentlywere brothers. The father of the girls asked to have the expected that its response will be such as to leave no ttwo testicles of the younger girl removed, whilst the elder commune, however indigent, without access to a remedygirli suffered from time to time from pains in her testicle, so efficacious beyond all others in combating the national thatt the question arose whether this operation, which might scourge. be1 called castration, was justified. The existence of these March 30th. malformations rise to some ___________________ naturally gave difficulty inthe selection of an occupation for the girls. VIENNA. Ulceration of the Skin after Diagnostic Application of the X Rays. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) It is not often that a single cautious application of the - x rays for the purpose of ascertaining the presence of metallic Centenary of the Operateurinstitute, objectsc in the human body leads to grave consequences. Such a was shown Professor at the same THE of the foundation of the case, however, by Lang centenary Operateurinstitutemeeting of the Gesellschaft der Aerzte. The patient was or school for in which was established surgeons Vienna, by a man who had been of swallowed several the Francis I. on the of Dr. was suspected having Emperor suggestion Kern, nails when in a condition. -

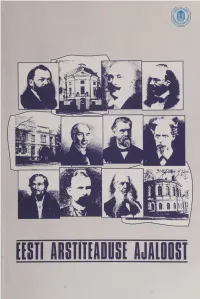

Eesti Arstiteaduse Uiioosi

EESTI ARSTITEADUSE UIIOOSI [tüll ШПТЕШИ Ш Ш 1 Koostanud Viktor Kalnin TARTU ÜLDCDOLI KIRJASTUS Kaane kujundanud Lemmi Koni Korrektor Leelo Jago ©Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 1996 ISBN 9985-56-148-1 Sisu trükk: AS Levileht Fotod, kaas ja köide: Tkrtu Ülikooli Kirjastuse trükikoda Tellimus nr. 138 SISUKORD Peter Ernst Wilde (1732-1785). Viktor Kalnin ............................................. 7 Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Luce (1750-1842). Boriss Schamardin, Viktor Kalnin. 12 Martin Ernst Styx (1759-1829). Viktor Kalnin................................................. 16 Karl Espenberg (1761-1822). Heino Gustavson................................................. 20 Daniel Georg Balk (1764-1826). Viktor Kalnin................................................. 25 Christian Friedrich von Deutch (1768-1843). Viktor Kalnin.......................... 30 David Hieronymus Grindel (1776-1836). Viktor Kalnin................................... 34 Karl Friedrich Burdach (1776-1847). Viktor Kalnin, Ela Lepp........................ 38 Johann Friedrich von Erdmann (1778-1846). Kuno Kõrge............................ 42 Karl Ernst von Baer (1792-1876). Maie Remmel............................................. 47 Friedrich Robert Faehlmann (1798-1850). Viktor Kalnin................................ 51 Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald (1803-1882). Viktor Kalnin .......................... 57 Philipp Jakob Karell (1806-1886). Viktor Kalnin............................................. 63 Friedrich Bidder (1810-1894). Viktor Kalnin .................................................. -

Konferenzzentrum Ernst Von Bergmann Am Tiefen See In

Konferenzzentrum Ernst von Bergmann am Tiefen See in Potsdam/Berlin Ernst von Bergmann (1836–1907), Chirurg, Lehrstuhlinhaber, Militärarzt und Autor, wird nach vielen Stationen seines Schaffens, u.a. in Dorpat, Riga und Würzburg, als Professor der Chirurgie und Direktor der chirurgischen Universitätsklinik nach Berlin berufen. Ernst von Bergmann revolutioniert die medizinische Wundbehandlung und ent- wickelt zahlreiche Operationstechniken weiter. In Berlin ist er auf dem Höhepunkt seiner medizinischen Laufbahn, und 1891 verwirklicht er seinen Traum: in Potsdam leben, in Berlin arbeiten. Er lässt die repräsentative Villa Bergmann in der Berliner Straße 62 errichten, umgeben von der zauberhaften Kulturlandschaft Potsdams. Seit 1991 trägt das Klinikum Ernst von Bergmann in Potsdam seinen Namen. Ernst von Bergmann (1836–1907) was a surgeon, professor, army medical officer and author. After working in many different cities, including Tartu, Riga and Würzburg, he was appointed professor of surgery and director of the surgical university hospital in Berlin. Ernst von Bergmann revolutionized medical wound management and developed a wide range of surgical techniques further. He reached the high point of his medical career in Berlin, and in 1891 finally made his dream of living in Potsdam and working in Berlin come true. The im- pressive Villa Bergmann on Berliner Straße 62 was built for him, surrounded by the charming man-made landscapes of Potsdam. The Ernst von Bergmann hospital in Potsdam has been Ernst von Bergmann existing under his name since 1991. Die Villa Bergmann befindet sich in einer der schönsten Lagen in Potsdam/Berlin. Das Gebäu- de im italienischen Stil liegt am Ufer des malerischen Tiefen Sees. -

Asepsis and Bacteriology: a Realignment of Surgery and Laboratory Science

Med. Hist. (2012), vol. 56(3), pp. 308–334. c The Author 2012. Published by Cambridge University Press 2012 doi:10.1017/mdh.2012.22 Asepsis and Bacteriology: A Realignment of Surgery and Laboratory Science THOMAS SCHLICH∗ Department of Social Studies of Medicine, McGill University, 3647 Peel Street, Montreal, Quebec, H3A 1X1, Canada Abstract: This paper examines the origins of aseptic surgery in the German-speaking countries. It interprets asepsis as the outcome of a mutual realignment of surgery and laboratory science. In that process, phenomena of surgical reality were being modelled and simplified in the bacteriological laboratory so that they could be subjected to control by the researcher’s hands and eyes. Once control was achieved, it was being extended to surgical practice by recreating the relevant features of the controlled laboratory environment in the surgical work place. This strategy can be seen in the adoption of Robert Koch’s bacteriology by German-speaking surgeons, and the resulting technical changes of surgery, leading to a set of beliefs and practices, which eventually came to be called ‘asepsis’. Keywords: Asepsis, Antisepsis, Surgery, Bacteriology If he were a surgeon, the laboratory scientists Louis Pasteur wrote in 1878, he would not only clean his instruments thoroughly, ‘but after having cleaned my hands with the greatest of care, I would subject them to rapid flaming’. Pasteur did this in his laboratory with all objects that came into contact with his microbial cultures, in order to avoid contamination. Furthermore, he ‘would use only lint, bandages and sponges previously exposed to air temperatures of 130–150 ◦C and use water that had been heated to temperatures of 1 110–120 ◦C’. -

Aus Der Klinik Für Urologie Der Medizinischen Fakultät Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin

Aus der Klinik für Urologie der Medizinischen Fakultät Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin DISSERTATION Die Herausbildung urologischer Kliniken in Berlin - Ein Beitrag zur Berliner Medizingeschichte zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doctor medicinae (Dr. med.) vorgelegt der Medizinischen Fakultät Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin von Slatomir Joachim Wenske aus Sliwen Gutachter: 1. Prof. Dr. D. Schnorr 2. PD Dr. H. Dietrich 3. Prof. Dr. D. Fahlenkamp Datum der Promotion: 30. September 2008 Professor Bernd Schönberger und Franz Blome junior gewidmet 1 - Einleitung 1 2 - Gegenwärtiger Forschungsstand und Methodik 4 3 - Erster Teil - Die Entwicklung der Urologie in Berlin 6 3.1 - Einführung in die Berliner Medizingeschichte und den Berliner 6 Krankenhausbau 3.2 - Die Entwicklung der urologischen Arztpraxis – 14 Die zweite Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts 3.3 - Die Blütezeit der Medizinischen Entwicklung - Der Beginn des 20. 23 Jahrhunderts 3.4 - Die Zeit des Nationalsozialismus - 1933-1945 30 3.5 - Die Zeit der Teilung - 1945-1990 40 3.5.1 - Besonderheiten der Entwicklung in Ost-Berlin 44 3.5.2 - Besonderheiten der Entwicklung in Westberlin 49 4 - Zweiter Teil - Die Herausbildung und Entwicklung der Urologischen 55 Abteilungen an den Berliner Krankenanstalten 4.1 - Die Charité 56 4.2 - Die Chirurgische Universitätsklinik in der Ziegelstrasse 65 4.3 - Das Universitätsklinikum Benjamin Franklin 71 4.4 - Das Städtische Krankenhaus Am Friedrichshain 73 4.5 - Das Städtische Krankenhaus Westend 82 4.6 - Das Rudolf-Virchow-Krankenhaus 89 4.7 - Das Städtische Krankenhaus Moabit 96 4.8 - Das Städtische Krankenhaus Am Urban 102 4.9 - Das Städtische Krankenhaus Neukölln 106 4.10 - Das Städtische Auguste-Viktoria-Krankenhaus 109 4.11 - Das Städtische Humboldt-Krankenhaus 112 4.12 - Das Städtische Klinikum Berlin-Buch 114 4.13 - Das Oskar-Ziethen Krankenhaus 120 4.14 - Das Städtische Krankenhaus Pankow 123 4.15 - Das St. -

![64 Andrzej Topij [574]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6985/64-andrzej-topij-574-7216985.webp)

64 Andrzej Topij [574]

ZAPISKI HISTORYCZNE — TOM LXXVI — ROK 2011 Zeszyt 4 ANDRZEJ TOPIJ (Bydgoszcz) THE ROLE OF THE DEUTSCHBALTEN IN THE CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF RUSSIA’S BALTIC PROVINCES IN THE 19th CENTURY Keywords: 19th century; Baltic Germans, Latvia, Estonia, culture, economy Th e Russian Empire was a conglomerate of various lands, nations, cultures and religions. Among the nations living in Russia some were of high cultural and political standards who took much pride in their centuries-old history. What was of paramount importance was that they belonged to Western civilization, so no wonder they constituted an alien element in the Russian state. Above all, were the Baltic Germans and the Poles. As far as the former were concerned, they inhabited the three Baltic Provinces: Kurland, Livland and Estland, encompassing almost all of present-day Estonia and Latvia. Baltic Germans living in these provinces took a dominant position in all spheres of life. Th e term „Baltic” came into use in the 1830s in connection with the preparation of the codifi cation of local laws. In the 1860s, the local Germans began to be called Balts (Balten) or German Balts (Deutschbalten), but I have also em- ployed the more modern term which spread gradually aft er 1918: Baltic Germans (die baltischen Deutschen). Besides, it will be borne in mind that the old terms, Estländer, Livländer and Kurländer, were being used at least until 19051. In spite of their numerical paucity (about 180 000 or 10% of the population in the region in 1881), the Baltic Germans played an enormous role in the develop- ment of almost all spheres of public life. -

A Brief History of Laryngectomy

Open Access Review Article DOI: 10.7759/cureus.8804 Losing One’s Voice to Save One’s Life: A Brief History of Laryngectomy Boyko Matev 1 , Asen Asenov 2 , George S. Stoyanov 3 , Lora T. Nikiforova 4 , Nikolay R. Sapundzhiev 4 1. Medicine, Medical University of Varna, Varna, BGR 2. Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Medical University of Plovdiv, Plovdiv, BGR 3. General and Clinical Pathology/Forensic Medicine and Deontology, Medical University of Varna, Varna, BGR 4. Otolaryngology, Medical University of Varna, Varna, BGR Corresponding author: George S. Stoyanov, [email protected] Abstract Laryngectomy is a surgical procedure that involves the surgical removal of the laryngeal complex, thereby separating the upper from the lower respiratory tracts, resulting in a tracheostomy. In this way, respiration is achieved at the expense of the patient’s voice. A neopharynx is formed, serving only as a digestive passage between the mouth and the esophagus. Until the introduction of the procedure, patients with laryngeal cancer were considered terminally ill. Most often, the title of “First recorded laryngectomy” is held by Theodor Billroth in 1873; however, the outcome of the operation itself was doubtful, with later attempts having a 50% mortality rate. The first major leap in reducing patient mortality rates was the introduction of the two-step laryngectomy, performed by Themistocles Gluck in 1881. This achievement, along with the general advancements in the field of surgery at the time allowed his student Johannes Sørensen to perfect the method and further develop it into a modified single-stage laryngectomy. This procedure is the basis of contemporary methods.