Copyright by Jared Michael Genova 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalrelations.Ourcuba.Com Cleveland Ballet in Havana

GlobalRelations.OurCuba.com 1-815-842-2475 Cleveland Ballet in Havana In Cuba from Thursday February 27th to Monday March 2, 2020 Day 1 – Thursday :: Arrive Cuba, Iconic Hotel, welcome dinner and evening to explore Depart to Havana via your own arranged flights. You should plan arriving Havana by mid-afternoon. It may take you some time to clear Cuban Immigration, get your bag and go through Customs. You will be met in the arrival hall, after clearing Customs, by our Cuban representative holding a ‘Cuba Explorer’ sign to take you to your hotel. They will have your name and will be monitoring your flight arrival in case there is a delay. Your first tour activity will be the welcome dinner and your guide will finalize details with you on arrival to your hotel. On departure from Cuba you will be asked to be at the airport 3 hours in advance. Havana’s International Airport arrival hall does have bathrooms. They may not have seats or tissue. This is normal in Cuba, so you may wish to bring packets of tissues. It is suggested to use the restroom on your flight before landing. On arrival at Havana’s José Martí International Airport proceed through Immigration. Your carry-on will once again be scanned. Give your ‘Health’ form to the nurses in white uniforms after you go through Immigration & screening. The important question they may ask is if you have been exposed to Ebola. Collect your bags and go through Customs giving them your blue customs form. You will be welcomed at the airport exterior lobby after you exit Cuban Customs. -

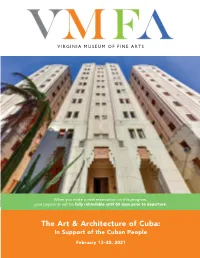

The Art & Architecture of Cuba

VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS When you make a new reservation on this program, your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. The Art & Architecture of Cuba: In Support of the Cuban People February 13–20, 2021 HIGHLIGHTS ENGAGE with Cuba’s leading creators in exclusive gatherings, with intimate discussions at the homes and studios of artists, a private rehearsal at a famous dance company, and a phenomenal evening of art and music at Havana’s Fábrica de Arte Cubano DELIGHT in a private, curator-led tour at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Havana, with its impressive collection of Cuban artworks and international masterpieces from Caravaggio, Goya, Rubens, and other legendary artists CELEBRATE and mingle with fellow travelers at exclusive receptions, including a cocktail reception with a sumptuous dinner in the company of the President of The Ludwig Foundation of Cuba and an after-tours tour and reception at the dazzling Ceramics Museum MEET the thought leaders who are shaping Cuban society, including the former Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, who will share profound insights on Cuban politics DISCOVER the splendidly renovated Gran Teatro de La Habana Alicia Alonso, the ornately designed, Neo-Baroque- style home to the Cuban National Ballet Company, on a private tour ENJOY behind-the-scenes tours and meetings with workers at privately owned companies, including a local workshop for Havana’s classic vehicles and a factory producing Cuban cigars VENTURE to the picturesque Cuban countryside for When you make a new reservation on this program, a behind-the-scenes tour of a beautiful tobacco plantation your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. -

Havanareporter YEAR VI

THE © YEAR VI Nº 7 APR, 6 2017 HAVANA, CUBA avana eporter ISSN 2224-5707 YOUR SOURCE OF NEWS & MORE H R Price: A Bimonthly Newspaper of the Prensa Latina News Agency 1.00 CUC, 1.00 USD, 1.20 CAN Caribbean Cooperation on Sustainable Development P. 3 P. 4 Cuba Health & Economy Sports Maisí Draws Tourists Science Valuable Cuban Boxing to Cuba’s Havana Hosts Sugar by Supports Enhanced Far East Regional Disability Products Transparency P.3 Conference P. 5 P. 13 P. 15 2 Cuba´s Beautiful Caribbean Keys By Roberto F. CAMPOS Many tourists who come to Cuba particularly love the beak known as Coco or White Ibis. Cayo Santa Maria, in Cuba’s the north-central region “Cayos” and become enchanted by their beautiful and Adjacent to it are the Guillermo and Paredón has become a particularly popular choice because of its very well preserved natural surroundings and range of Grande keys, which are included in the region´s tourism wonderful natural beauty, its infrastructure and unique recreational nautical activities. development projects. Cuban culinary traditions. These groups of small islands include Jardines del Rey Cayo Coco is the fourth largest island in the Cuban 13km long, two wide and boasting 11km of prime (King´s Gardens), one of Cuba´s most attractive tourist archipelago with 370 square kilometers and 22 beachfront, Cayo Santa María has small islands of destinations, catering primarily to Canadian, British kilometers of beach. pristine white sands and crystal clear waters. and Argentine holidaymakers, who praise the natural Cayo Guillermo extends to 13 square kilometers Other outstandingly attractive islets such as environment, infrastructure and service quality. -

MOA Journeys: Cuba 2014

Thursday, 20 November Day 1 Arrive in Havana Arrive in Havana at Jose Marti International Airport. Meet your guide then transfer to your 4-star hotel in the heart of the old city. All transport within Cuba is by private deluxe motor coach. Upon arrival in the city, the vibrancy of the people is one of the first things you will notice. Also striking is the fact that, day or night, music can be heard and most evenings, somewhere in the city, people can be found dancing in the streets. The rich history of the island is apparent in the faces of the people. They are the descendants of the Spanish conquistadores who colonised the island in the sixteenth century and African slaves brought over to work on the tobacco and sugar plantations. Overnight in Havana. Meal plan: Tonight, you’ll enjoy a welcome dinner & cocktails*, meet your Adventures Abroad tour guide, mingle with the Museum of Anthropology representatives and members like you, and enjoy an introductory presentation by Without Masks curator, Orlando Hernández. *subject to flight schedules Friday, 21 November Day 2 Havana: Centre City Tour Cuba's cosmopolitan capital was once one of the world's most prosperous ports and the third most populous city in the Americas. As La Llave del Mundo (Key of the World), she saw riches from Mexico, Peru, and Manila pass through her sheltered harbour to Spain. Havana shows evidence of long neglect but her beauty shines through an amalgam of Spanish, African, colonial, communist, and capitalist influences. Today we have a tour of Old Havana, including a stroll down Prado Avenue, for many years Havana's most important and impressive avenue. -

Music Production and Cultural Entrepreneurship in Today’S Havana: Elephants in the Room

MUSIC PRODUCTION AND CULTURAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN TODAY’S HAVANA: ELEPHANTS IN THE ROOM by Freddy Monasterio Barsó A thesis submitted to the Department of Cultural Studies In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2018) Copyright ©Freddy Monasterio Barsó, 2018 Abstract Cultural production and entrepreneurship are two major components of today’s global economic system as well as important drivers of social development. Recently, Cuba has introduced substantial reforms to its socialist economic model of central planning in order to face a three-decade crisis triggered by the demise of the USSR. The transition to a new model, known as the “update,” has two main objectives: to make the state sector more efficient by granting more autonomy to its organizations; and to develop alternative economic actors (small private businesses, cooperatives) and self-employment. Cultural production and entrepreneurship have been largely absent from the debates and decentralization policies driving the “update” agenda. This is mainly due to culture’s strategic role in the ideological narrative of the ruling political leadership, aided by a dysfunctional, conservative cultural bureaucracy. The goal of this study is to highlight the potential of cultural production and entrepreneurship for socioeconomic development in the context of neoliberal globalization. While Cuba is attempting to advance an alternative socialist project, its high economic dependency makes the island vulnerable to the forces of global neoliberalism. This study focuses on Havana’s music sector, particularly on the initiatives, musicians and music professionals operating in the informal economy that has emerged as a consequence of major contradictions and legal gaps stemming from an outdated cultural policy and ambiguous regulation. -

Download Our Cuba Brochure (PDF Format)

CUBA � � � � � � � � � ���������������������� ���������������������� ������������ � � � � � � � � � ���������������������� ���������������������� ������������ � � � � � � � � � ���������������������� ���������������������� ������������ CARIBBEAN DESTINATIONS • TABLE OF CONTENTS • CUBA INTRODUCTION P: 2-3 EXPLORE & DISCOVER CUBA P: 14-16 BOUTIQUE HOTELS, HAVANA P: 4-5 – TOURS HAVANA HOTELS P: 6 CAR HIRE & FLEXIDRIVE P: 17 CIENFUEGOS P: 7 YACHTING & SCUBA DIVING P: 18 VILLA CLARA P: 8 HONEYMOONS & WEDDINGS P: 19 TRINIDAD P: 9 JAMAICA P: 20 VINALES VALLEY & PINAR DEL RIO P: 10 MEXICO P: 21 SANTIAGO DEL CUBA & CAMAGUEY P: 11 CUBAN CULTURE P: 22 VARADERO P: 12 GETTING TO CUBA P: 23 THE KEYS P: 13 TERMS & CONDITIONS P: 24 CARIBBEAN DESTINATIONS WHY BOOK WITH TAILOR MADE TRAVEL We are delighted to introduce you to our CARIBBEAN DESTINATIONS? Caribbean Destinations can offer the most dedicated Cuba brochure, although this is merely Our expertise extends through the USA and comprehensive and flexible tailor-made holiday an introduction to the myriad of Cuban travel West Indies area, enabling us to construct and to Cuba, backed by the combined experience of opportunities that are available through Caribbean tailor make travel packages to suit all individual handling many hundreds of tailor made travelers Destinations. We have excellent personal knowledge budgets saving you time and money. arriving into Cuba every year. of Cuba and regularly travel to the island to Our specialist team of travel consultants, all keep ahead of developments in this fascinating -

Viaje a La Habana 1

HABANA HABANA Texto / Ricardo Angoso VIAJE A LA HABANA 1. Estos son los que lugares que edificio robusto, recio e imperial hemos seleccionado para tu viaje, se encuentra la Real Fábrica de aunque no debes perder de vista Partagas, que se puede conocer a que un buen viajero siempre impro- través de sus visitas guiadas y siem- visa su itinerario después de haber pre pagadas. Cerca del capitolio, y 85 leído lo suficiente sobre el lugar como curiosidad, se encuentra el diario16 para realizar su propia visita con sus Centro Gallego, emblemático lugar señas de identidad personales y de la inmigración española llegada sus ‘descubrimientos’ en ruta. a la isla y construido por emigran- 1. El malecón. Es el lugar más tes gallegos entre 1907 y 1914. Por emblemático de la ciudad y es una cierto, en Cuba conviene recordar suerte de dique de ocho kilóme- al viajero que todas las visitas a tros de longitud que separa, o monumentos y museos siempre une, según se mire, a La Habana son de pago obligado. 2. del mar. Fue construido en 1901, 3. El Gran Teatro de la Habana. durante el periodo de gobierno y Muy cerca del Capitolio pode- administración norteamericana, y mos conocer el Gran Teatro de recorre la costa desde el castillo la ciudad que, con 2.000 butacas, de San Salvador de la Punta, en es el más grande de la isla y el La Habana vieja, hasta el fuerte de más antiguo del Nuevo Mundo o Santa Dorotea. El recorrido a través las Américas, siendo muy bello y del malecón muestra a un lado exquisito en su decoración exterior unos edificios bastante abando- e interior. -

Dance & Theater 28 Literature 29 Painting 31 Cinema & Television 32

© Lonely Planet Publications Arts Dance & Theater 28 Literature 29 Painting 31 Cinema & Television 32 Arts Far from dampening Habana’s artistic heritage, the Cuban revolution actually strengthened it, ridding the city of insipid foreign commercial influences and putting in their place a vital network of art schools, museums, theater groups and writers unions. Indeed, Cuba is one of the few countries in the world where mass global culture has yet to penetrate and where being ‘famous’ is usually more to do with genuine talent than good looks, luck or the right agent. Despite the all-pervading influence of the Cuban government in the country’s vibrant cultural life, Habana’s art world remains surprisingly experimental and varied. Thanks to generous state subsidies over the past 50 years, traditional cultural genres such as Afro- Cuban dance and contemporary ballet have been enthusiastically revisited and revalued, resulting in the international success of leading Cuban dance troupes such as the Habana- based Conjunto Folklórico Nacional (p139 ) and the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. Much of Cuba’s best art is exhibited in apolitical genres such as pop art and opera, while more cutting-edge issues can be found in movies such as Fresa y Chocolate, a film that boldly questioned social mores and pushed homosexuality onto the public agenda. DANCE & THEATER Described by aficionados as ‘a vertical representation of a horizontal act,’ Cuban dancing is famous for its libidinous rhythms and sensuous moves. It comes as no surprise to discover that the country has produced some of the world’s most exciting dancers. With an innate musical rhythm at birth and the ability to replicate perfect salsa steps by the age of two or three, Cubans are natural performers who approach dance with a complete lack of self- consciousness – something that leaves most visitors from Europe or North America feeling as if they’ve got two left feet. -

Guía De La Habana Ingles.Indd

La Habana Guide Free / ENGLISH EDITORIAL BOARD Oscar González Ríos (President), Chief of Information: Mariela Freire Edition y Corrección:Infotur de La Habana, Armando Javier Díaz.y Pedro Beauballet. Design and production: MarielaTriana Images, Photomechanics Printers: PUBLICITUR Distribution: Pedro Beauballet Cover Photograph: Alfredo Saravia National Office of Tourist Information: Calle 28 No.303, e/ 3ra y 5ta,Miramar, PLaya Tel:(537) 72040624 / 72046635 www.cubatravel.cu Summary Havana, hub city 6 Attractions 8 Directory Tour Bus 27 Cuban tobacco 31 Lodgings 32 Where to Eat 43 Where to listen to music 50 Galeries and Malls 52 Sports Centers 54 Religious Institutions and Fraternal Associations 55 Museums, Theaters and Art Galeries 56 Movie Theaters, Libraries 58 Customs Regulations 60 Currency 61 Assistance and Health 64 Travel Agencies 67 Telephones 68 Embassies 70 Transport 72 Airlines 74 Events 76 To Have in Mind 78 Information centers Infotur 79 Havana Hub City Founded in 1514, the Village San Cristobal de La Habana obtained the title of city on December 1592 and in 1607 was reognized as official capital of the colony. colonial architecture, with an ample range of Arab, Spanish, Italian and Greek-latin. We assist to see a certain Architecture eclecticism, an adaptation to sensations Havana became, over 200 years ago, and desires of the island. the most important and attractive city of the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, Among these creole versions, stand enchanted city for its architecture. out the portico with columns. And, less frequently, the arches that among Fronts with pilasters flanking double other formulas, show a certain liberty, doors, halfpoint arches, columns, functionality and decorative simplicity. -

Art Tour Itinerary

Art Tour Itinerary Day 1 Havana Island Arrival, Private Welcome Drinks with an Artist, Dinner (Fábrica de Arte Cubano), Private Tour and Night Out at La Fábrica Day 2 Havana Breakfast, Exploring Old Havana, Visit & Discussion with an Artist in Old Havana, Lunch (paladar), Vintage Convertible Ride, Salsa Lesson, Rest at Accommodation, Private Dinner with a Local Chef Day 3 Havana Breakfast, Cuban Tile Studio, Museum of Fine Arts, El Gran Teatro de La Habana, Lunch (mojito break), Cultural Immersion Tour, Rum Tasting Experience, Rest at Accommodation, Dinner, Salsa Dancing with Locals Day 4 Havana Breakfast, Home Art Studio Visit and Workshop, Lunch, Contemporary Art Space, San Isidro Experience, Rest at Accommodation, Farewell Dinner, Live Music (last night) Day 5 Havana Breakfast, Optional Morning Activity (local art collective), Departure Flight from Havana Airport Art Tour Itinerary Day 1 Havana Island Arrival, Private Welcome Drinks with an Artist, Dinner (Fábrica de Arte Cubano), Private Tour and Night Out at La Fábrica Time Activity Description 2:00 PM - Island Arrival Your driver will meet you at the airport, and you’ll be taken 5:00 PM to your accommodation to freshen up. 6:30 PM - Private Welcome Welcome to Havana! Kick-off your cultural immersion with 7:30 PM Drinks with an drinks and a personal welcome from an artist in a local up- Artist and-coming art space. 8:00 PM - Dinner (Fábrica de Sit down at one of Havana’s trendiest restaurants located 9:30 PM Arte Cubano) inside the VIP section of the famous Fábrica de Arte Cubano. 9:30 PM - Private Tour and Enjoy a private tour of Fábrica de Arte Cubano, a must-see Night Out at La Cuban art installation and center of Havana nightlife! Enjoy Fábrica a classic mojito as you explore three floors of art galleries, live music, DJs and more. -

CUBA – PAST and PRESENT

CUBA – PAST and PRESENT April 24 – 30, 2004 presented by HARRISONBURG 90.7 CHARLOTTESVILLE 103.5 LEXINGTON 89.9 WINCHESTER 94.5 FARMVILLE 91.3 1-800-677-9672 CUBA ~ PAST and PRESENT WMRA Public Radio proudly presents our first tour to Cuba…..an educational travel experience that is truly “off the beaten path.” Learn about the art, architecture, and history of this fascinating Caribbean island that is as beautiful as it is interesting. Experience everything Cuba has to offer….from its most famous museums to the salsa and rumba rhythms heard in the streets to its breathtaking vistas. A portion of your tour is a tax-deductible donation to WMRA Public Radio, helping to support the news and classical music programming we bring you each day. This educational exchange program is licensed for travel to Cuba to promote cultural exchange and people to people contact. We look forward to seeing you on another one of our exciting tours! FULLY ESCORTED TOUR INCLUDES Round-Trip Air Charter Transportation from Miami 2 Nights Havana — 2 Nights Cienfuegos — 2 Nights Havana Private Motor Coach as per Itinerary Full Buffet Breakfast Daily — 3 Lunches — 4 Dinners All Cultural Programs as per Itinerary Gran Teatro de la Habana Performance All Entrance Fees, Gratuities, Service Fees, and Visa Fees $2,990 per Person, based on Double Occupancy DAILY ITINERARY Saturday, April 24 - Depart Miami on an air charter flight to Cuba. Arrive in Havana and transfer by private motor coach to our hotel. Relax during the orientation coach tour of Havana as we pass by the -

Havanareporter YEAR VI

THE © YEAR VI Nº 10 MAY, 18 2017 HAVANA, CUBA avana eporter ISSN 2224-5707 YOUR SOURCE OF NEWS & MORE H R Price: A Bimonthly Newspaper of the Prensa Latina News Agency 1.00 CUC, 1.00 USD, 1.20 CAN P. 4 Cuba’s P. 4 Martin Luther King POLITICAL COUNCIL Center Turns 30 Tourism Culture Economy Sports Golf The Oldest Theater Cuba and Mississippi Hemingway Tees Off in Latin Talk About International Yacht In Cuba America Trade Club At 25 P.2 P.10 P. 14 P. 15 2 TOUURISM Cruise Ships Now Adorn Havana’s Beautiful Bay Text and Photos By Roberto F.CAMPOS The new reality of cruise ships in Cuba and in Havana principal sea port – was renovated to cater to the in particular, are symbolic of the impressive growth in requirements of cruise ship companies. the Island’s booming tourism sector. Nowadays, the sight of a modern cruise liner Cruises to Cuba were becoming increasingly in Havana‘s harbor is a far more frequent affair popular and the reestablishment of diplomatic that compels passers-by to pause and take in such relations between Washington and Havana, magnificent sight. undoubtedly helped return this premium destination in its rightful place. CRUISE SHIPS INDUSTRY GROWTH Much of today’s tourism industry developments in Cuba are focused on cruise ship visits to the island, The custom-built cruise ships now in use reflect present which greatly depend on the continued easing of developments in the sector and the construction Blockade related prohibitions imposed by the US of bigger ships with enhanced passenger capacity, ships are the AIDAstella and MSC Preziosa ( delivered in on citizens wishing to visit the beautiful Cuban combined with the growing choice of cruises offered, March), the Norwegian Breakaway and Europa 2 (April) archipelago.