Havana—Main Text

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Globalrelations.Ourcuba.Com Cleveland Ballet in Havana

GlobalRelations.OurCuba.com 1-815-842-2475 Cleveland Ballet in Havana In Cuba from Thursday February 27th to Monday March 2, 2020 Day 1 – Thursday :: Arrive Cuba, Iconic Hotel, welcome dinner and evening to explore Depart to Havana via your own arranged flights. You should plan arriving Havana by mid-afternoon. It may take you some time to clear Cuban Immigration, get your bag and go through Customs. You will be met in the arrival hall, after clearing Customs, by our Cuban representative holding a ‘Cuba Explorer’ sign to take you to your hotel. They will have your name and will be monitoring your flight arrival in case there is a delay. Your first tour activity will be the welcome dinner and your guide will finalize details with you on arrival to your hotel. On departure from Cuba you will be asked to be at the airport 3 hours in advance. Havana’s International Airport arrival hall does have bathrooms. They may not have seats or tissue. This is normal in Cuba, so you may wish to bring packets of tissues. It is suggested to use the restroom on your flight before landing. On arrival at Havana’s José Martí International Airport proceed through Immigration. Your carry-on will once again be scanned. Give your ‘Health’ form to the nurses in white uniforms after you go through Immigration & screening. The important question they may ask is if you have been exposed to Ebola. Collect your bags and go through Customs giving them your blue customs form. You will be welcomed at the airport exterior lobby after you exit Cuban Customs. -

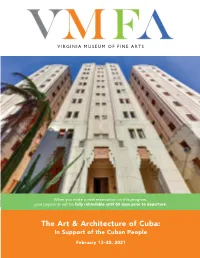

The Art & Architecture of Cuba

VIRGINIA MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS When you make a new reservation on this program, your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. The Art & Architecture of Cuba: In Support of the Cuban People February 13–20, 2021 HIGHLIGHTS ENGAGE with Cuba’s leading creators in exclusive gatherings, with intimate discussions at the homes and studios of artists, a private rehearsal at a famous dance company, and a phenomenal evening of art and music at Havana’s Fábrica de Arte Cubano DELIGHT in a private, curator-led tour at the National Museum of Fine Arts of Havana, with its impressive collection of Cuban artworks and international masterpieces from Caravaggio, Goya, Rubens, and other legendary artists CELEBRATE and mingle with fellow travelers at exclusive receptions, including a cocktail reception with a sumptuous dinner in the company of the President of The Ludwig Foundation of Cuba and an after-tours tour and reception at the dazzling Ceramics Museum MEET the thought leaders who are shaping Cuban society, including the former Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs, who will share profound insights on Cuban politics DISCOVER the splendidly renovated Gran Teatro de La Habana Alicia Alonso, the ornately designed, Neo-Baroque- style home to the Cuban National Ballet Company, on a private tour ENJOY behind-the-scenes tours and meetings with workers at privately owned companies, including a local workshop for Havana’s classic vehicles and a factory producing Cuban cigars VENTURE to the picturesque Cuban countryside for When you make a new reservation on this program, a behind-the-scenes tour of a beautiful tobacco plantation your payments will be fully refundable until 60 days prior to departure. -

Un Pueblo De ¡Patria O Muerte!

“Lo imposible, es posible”. José Martí ÓRGANO DEL COMITÉ PROVINCIAL DEL PARTIDO COMUNISTA DE CUBA / CAMAGÜEY, 21 DE SEPTIEMBRE DEL 2019 “AÑO 61 DE LA REVOLUCIÓN”. No. 40. AÑO LXI. 20 Ctvs. (ISSN 0864-0866). Cierre: 8:00 p.m. Un pueblo de ¡Patria o Muerte! El Buró Provincial del Partido extiende una afectuosa felicita- ción a los investigadores, es- pecialistas, funcionarios, técni- cos, y muy especialmente a los activistas y colaboradores del Sistema de Estudios Sociopo- líticos y de Opinión, en su ani- versario 52. Ustedes constitu- yen eslabón fundamental para que la dirección del país en todos los niveles ponga cada vez más, como ha llamado Raúl, “el oído en la tierra”. Las aspiraciones, las críticas, las sugerencias, el respaldo o el rechazo del pueblo ante cada proceso determinan la toma de decisiones, por lo que el histórico momento que vive nuestra Revolución reafirma la importancia de su labor cotidiana, a la cual sabemos continuarán dedicando su mayor esfuerzo, entusiasmo y responsabilidad. “Estamos trabajando distinto, pero con “¿Por qué renunciar a que los carros es- gía, deseos de hacer, ellos en pocos años los mismos principios de solidaridad, la- tatales recojan personas en las paradas; ocuparán nuestros cargos y ahora hay que boriosidad, con la misma voluntad y con- a que las panaderías y centros de elabo- aprovechar para que aprendan en tiempo vicción de victoria que caracteriza a los cu- ración tengan más de una fuente para la real esos cuadros del futuro”. banos”, expresó Miguel Díaz-Canel Bermú- cocción; a seguir desplazando -

Havanareporter YEAR VI

THE © YEAR VI Nº 7 APR, 6 2017 HAVANA, CUBA avana eporter ISSN 2224-5707 YOUR SOURCE OF NEWS & MORE H R Price: A Bimonthly Newspaper of the Prensa Latina News Agency 1.00 CUC, 1.00 USD, 1.20 CAN Caribbean Cooperation on Sustainable Development P. 3 P. 4 Cuba Health & Economy Sports Maisí Draws Tourists Science Valuable Cuban Boxing to Cuba’s Havana Hosts Sugar by Supports Enhanced Far East Regional Disability Products Transparency P.3 Conference P. 5 P. 13 P. 15 2 Cuba´s Beautiful Caribbean Keys By Roberto F. CAMPOS Many tourists who come to Cuba particularly love the beak known as Coco or White Ibis. Cayo Santa Maria, in Cuba’s the north-central region “Cayos” and become enchanted by their beautiful and Adjacent to it are the Guillermo and Paredón has become a particularly popular choice because of its very well preserved natural surroundings and range of Grande keys, which are included in the region´s tourism wonderful natural beauty, its infrastructure and unique recreational nautical activities. development projects. Cuban culinary traditions. These groups of small islands include Jardines del Rey Cayo Coco is the fourth largest island in the Cuban 13km long, two wide and boasting 11km of prime (King´s Gardens), one of Cuba´s most attractive tourist archipelago with 370 square kilometers and 22 beachfront, Cayo Santa María has small islands of destinations, catering primarily to Canadian, British kilometers of beach. pristine white sands and crystal clear waters. and Argentine holidaymakers, who praise the natural Cayo Guillermo extends to 13 square kilometers Other outstandingly attractive islets such as environment, infrastructure and service quality. -

MOA Journeys: Cuba 2014

Thursday, 20 November Day 1 Arrive in Havana Arrive in Havana at Jose Marti International Airport. Meet your guide then transfer to your 4-star hotel in the heart of the old city. All transport within Cuba is by private deluxe motor coach. Upon arrival in the city, the vibrancy of the people is one of the first things you will notice. Also striking is the fact that, day or night, music can be heard and most evenings, somewhere in the city, people can be found dancing in the streets. The rich history of the island is apparent in the faces of the people. They are the descendants of the Spanish conquistadores who colonised the island in the sixteenth century and African slaves brought over to work on the tobacco and sugar plantations. Overnight in Havana. Meal plan: Tonight, you’ll enjoy a welcome dinner & cocktails*, meet your Adventures Abroad tour guide, mingle with the Museum of Anthropology representatives and members like you, and enjoy an introductory presentation by Without Masks curator, Orlando Hernández. *subject to flight schedules Friday, 21 November Day 2 Havana: Centre City Tour Cuba's cosmopolitan capital was once one of the world's most prosperous ports and the third most populous city in the Americas. As La Llave del Mundo (Key of the World), she saw riches from Mexico, Peru, and Manila pass through her sheltered harbour to Spain. Havana shows evidence of long neglect but her beauty shines through an amalgam of Spanish, African, colonial, communist, and capitalist influences. Today we have a tour of Old Havana, including a stroll down Prado Avenue, for many years Havana's most important and impressive avenue. -

Music Production and Cultural Entrepreneurship in Today’S Havana: Elephants in the Room

MUSIC PRODUCTION AND CULTURAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP IN TODAY’S HAVANA: ELEPHANTS IN THE ROOM by Freddy Monasterio Barsó A thesis submitted to the Department of Cultural Studies In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (September, 2018) Copyright ©Freddy Monasterio Barsó, 2018 Abstract Cultural production and entrepreneurship are two major components of today’s global economic system as well as important drivers of social development. Recently, Cuba has introduced substantial reforms to its socialist economic model of central planning in order to face a three-decade crisis triggered by the demise of the USSR. The transition to a new model, known as the “update,” has two main objectives: to make the state sector more efficient by granting more autonomy to its organizations; and to develop alternative economic actors (small private businesses, cooperatives) and self-employment. Cultural production and entrepreneurship have been largely absent from the debates and decentralization policies driving the “update” agenda. This is mainly due to culture’s strategic role in the ideological narrative of the ruling political leadership, aided by a dysfunctional, conservative cultural bureaucracy. The goal of this study is to highlight the potential of cultural production and entrepreneurship for socioeconomic development in the context of neoliberal globalization. While Cuba is attempting to advance an alternative socialist project, its high economic dependency makes the island vulnerable to the forces of global neoliberalism. This study focuses on Havana’s music sector, particularly on the initiatives, musicians and music professionals operating in the informal economy that has emerged as a consequence of major contradictions and legal gaps stemming from an outdated cultural policy and ambiguous regulation. -

Paper Will Present Several Study Cases Highlighting the Possibilities of This Technique As Well As Particular Challenges Faced in Cuba

8th European Workshop On Structural Health Monitoring (EWSHM 2016), 5-8 July 2016, Spain, Bilbao www.ndt.net/app.EWSHM2016 Health monitoring and damage assessment using a georadar: case studies and challenges in Cuba Ernesto L. CHAGOYÉN Méndez1, Carlos A. RECAREY Morfa1, Alexis CLARO Duménigo1, Rafael RAMÍREZ Díaz2, Gregorio ARAGÓN3, Marja RODRÍGUEZ Castellanos3, Vivian ELENA Parnas4, Geert LOMBAERT5, Dirk ROOSE6 1 Wpkxgtukfcf"Egpvtcn"ÐOctvc"CdtgwÑ"fg"Ncu"Xknncu (UCLV), Santa Clara, Villa Clara, CUBA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 Empresa Nacional de Investigaciones Aplicadas (ENIA), La Habana, CUBA [email protected] http://www.ndt.net/?id=20015 3Estación Comprobadora de Puentes (ECP), Placetas, Villa Clara, CUBA 4 Kpuvkvwvq"Uwrgtkqt"Rqnkvfiepkeq"ÐLqufi"Cpvqpkq"Gejgxgtt‡cÑ"*KURLCG+."EWDC" [email protected] 5 Structural Mechanic Section, Civil Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, KU Leuven, BELGIUM [email protected] 6 Computer Science Department, Faculty of Engineering, KU Leuven, BELGIUM [email protected] More info about this article: Keywords: structural health monitoring, railway brigde, vibration analysis, georadar Abstract Cuba has a dense railway network with a high number of bridges. The railway network was established 177 years ago and had his golden age in the past century. Steel bridges in this network are often more than 100 years old. According to data from 2005, 30 % of the bridges are in bad condition and a speed limit of 15 km/h was imposed. The highway network and communication infrastructure are characterized by similar problems, for example, 59 television towers have failed in the period 1996 Î 2012 of which 70% were in operation for at least 30 years. -

Download Our Cuba Brochure (PDF Format)

CUBA � � � � � � � � � ���������������������� ���������������������� ������������ � � � � � � � � � ���������������������� ���������������������� ������������ � � � � � � � � � ���������������������� ���������������������� ������������ CARIBBEAN DESTINATIONS • TABLE OF CONTENTS • CUBA INTRODUCTION P: 2-3 EXPLORE & DISCOVER CUBA P: 14-16 BOUTIQUE HOTELS, HAVANA P: 4-5 – TOURS HAVANA HOTELS P: 6 CAR HIRE & FLEXIDRIVE P: 17 CIENFUEGOS P: 7 YACHTING & SCUBA DIVING P: 18 VILLA CLARA P: 8 HONEYMOONS & WEDDINGS P: 19 TRINIDAD P: 9 JAMAICA P: 20 VINALES VALLEY & PINAR DEL RIO P: 10 MEXICO P: 21 SANTIAGO DEL CUBA & CAMAGUEY P: 11 CUBAN CULTURE P: 22 VARADERO P: 12 GETTING TO CUBA P: 23 THE KEYS P: 13 TERMS & CONDITIONS P: 24 CARIBBEAN DESTINATIONS WHY BOOK WITH TAILOR MADE TRAVEL We are delighted to introduce you to our CARIBBEAN DESTINATIONS? Caribbean Destinations can offer the most dedicated Cuba brochure, although this is merely Our expertise extends through the USA and comprehensive and flexible tailor-made holiday an introduction to the myriad of Cuban travel West Indies area, enabling us to construct and to Cuba, backed by the combined experience of opportunities that are available through Caribbean tailor make travel packages to suit all individual handling many hundreds of tailor made travelers Destinations. We have excellent personal knowledge budgets saving you time and money. arriving into Cuba every year. of Cuba and regularly travel to the island to Our specialist team of travel consultants, all keep ahead of developments in this fascinating -

Antigua Estación De Ferrocarriles En Camagüey

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla Facultad de Arquitectura Colegio de Diseño Gráfico TESIS PRESENTADA PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE: LICENCIATURA EN DISEÑO GRÁFICO Identidad corporativa de la Antigua Estación de Ferrocarriles en Camagüey. Presenta: María Fernanda Manilla Hernández Directora: Mtra. Elda Emma Lobo Vázquez Asesoras: Mtra. Adriana Quiroz Hernández //1 Mtra. Beatriz Gamboa Canales Fecha de entrega e impresión: Abril 2017 3 TESIS PARA OBTENER EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN DISEÑO GRÁFICO Identidad corporativa Antigua Estación de Ferrocarriles en Camagüey. María Fernanda Manilla Hernández Directora: Mtra. Elda Emma Lobo Vázquez 5 Asesoras: Mtra. Adriana Quiroz Hernández //Mtra. Beatriz Gamboa Canales // Arq. Ariadna Hernández Ávila A mi madre Lidia Por haberme apoyado en todo momento, por sus consejos, sus valores, por la motivación constante que me ha permitido ser una persona de bien, pero más que nada, por su amor. A mis padres por ser el pilar fundamental en todo lo que soy, en toda mi educación, tanto académica, como de la vida, por su incondicional apoyo perfectamente mantenido a través del tiempo. Todo este trabajo ha sido posible gracias a ellos. Lidia Hernández Juárez Seffh Ramírez Pérez y Fulgencio Manilla Hernández Familia Manilla Hernández Familia Hernández Juárez Dedico esta tesis principalmente a mi familia por apoyarme cuando lo necesité, y que siempre estuvo ahí ante cualquier situación. Por último dedico esta tesis a todos los diseñadores gráficos que se están aventurando en este mar de creatividad he innovación y diciéndoles que si se puede crear algo distinto, porque creatividad y pasión sobra, sólo hay que saber luchar por alcanzar esa meta tan apreciada. -

Viaje a La Habana 1

HABANA HABANA Texto / Ricardo Angoso VIAJE A LA HABANA 1. Estos son los que lugares que edificio robusto, recio e imperial hemos seleccionado para tu viaje, se encuentra la Real Fábrica de aunque no debes perder de vista Partagas, que se puede conocer a que un buen viajero siempre impro- través de sus visitas guiadas y siem- visa su itinerario después de haber pre pagadas. Cerca del capitolio, y 85 leído lo suficiente sobre el lugar como curiosidad, se encuentra el diario16 para realizar su propia visita con sus Centro Gallego, emblemático lugar señas de identidad personales y de la inmigración española llegada sus ‘descubrimientos’ en ruta. a la isla y construido por emigran- 1. El malecón. Es el lugar más tes gallegos entre 1907 y 1914. Por emblemático de la ciudad y es una cierto, en Cuba conviene recordar suerte de dique de ocho kilóme- al viajero que todas las visitas a tros de longitud que separa, o monumentos y museos siempre une, según se mire, a La Habana son de pago obligado. 2. del mar. Fue construido en 1901, 3. El Gran Teatro de la Habana. durante el periodo de gobierno y Muy cerca del Capitolio pode- administración norteamericana, y mos conocer el Gran Teatro de recorre la costa desde el castillo la ciudad que, con 2.000 butacas, de San Salvador de la Punta, en es el más grande de la isla y el La Habana vieja, hasta el fuerte de más antiguo del Nuevo Mundo o Santa Dorotea. El recorrido a través las Américas, siendo muy bello y del malecón muestra a un lado exquisito en su decoración exterior unos edificios bastante abando- e interior. -

C09045.Pdf (688.9Kb)

Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas Facultad de Ingeniería Civil Departamento de Ingeniería Civil TRABAJO DE DIPLOMA Proyecto para la reconstrucción del Ramal Cumanayagua Autor: Hamry Cabrera Martínez Tutor: Ing. Juan Lima Menéndez Santa Clara 2009 "Año del 50 aniversario del triunfo de la revolución" i PENSAMIENTO “A SER POSIBLE, EL FERROCARRIL DEBE PASAR POR LAS CIUDADES PRINCIPALES CERCANAS A LA VÍA, O CONSTRUIR RAMALES QUE LLEVEN A ELLAS”. JOSÉ MARTÍ. ii DEDICATORIA A QUIENES CON SU INFINITO CARIÑO, EJEMPLO Y SACRIFICIO HAN SABIDO EDUCARME Y FORJARME COMO HOMBRE DE BIEN. MI FAMILIA. EN ESPECIAL MIS PADRES Y ABUELA PATERNA. iii AGRADECIMIENTOS A TODAS AQUELLAS PERSONAS QUE DE UNA FORMA U OTRA HAN COLABORADO EN LA REALIZACIÓN EXITOSA DEL PRESENTE TRABAJO. DESTACANDO: A CARLOS CRISTÓBAL MARTÍNEZ MARTÍNEZ. A CARLOS MARTÍNEZ CABRERA. A YULIET GONZALES MADARIAGA. Y AL TUTOR Ing. JUAN LIMA MENÉNDEZ. iv RESUMEN En la actualidad, se evidencia la importancia de mejorar la transportación ferroviaria en Cuba por el consumo de petróleo que como promedio es de 9,5 gramo-petróleo- equivalente, en relación con el transporte automotor (camiones) que es de 28 gramo- petróleo-equivalente; esto demuestra la economía del ferrocarril. Para resolver esta necesidad económica se realizan diferentes investigaciones encaminadas a solucionar la problemática del transporte ferroviario que afecta a la economía y a las poblaciones cubanas. En este contexto nacional, el presente trabajo ha abordado el tema de un proyecto para la reconstrucción del Ramal Cumanayagua trazándose como problema científico el siguiente: ¿cómo dar cobertura a las necesidades de transportación ferroviarias de la población y la industria militar en la zona de Cumanayagua? Primeramente se realizó una revisión bibliográfica del tema objeto de estudio, así como un diagnóstico que permitió definir el estado actual del problema científico. -

Dance & Theater 28 Literature 29 Painting 31 Cinema & Television 32

© Lonely Planet Publications Arts Dance & Theater 28 Literature 29 Painting 31 Cinema & Television 32 Arts Far from dampening Habana’s artistic heritage, the Cuban revolution actually strengthened it, ridding the city of insipid foreign commercial influences and putting in their place a vital network of art schools, museums, theater groups and writers unions. Indeed, Cuba is one of the few countries in the world where mass global culture has yet to penetrate and where being ‘famous’ is usually more to do with genuine talent than good looks, luck or the right agent. Despite the all-pervading influence of the Cuban government in the country’s vibrant cultural life, Habana’s art world remains surprisingly experimental and varied. Thanks to generous state subsidies over the past 50 years, traditional cultural genres such as Afro- Cuban dance and contemporary ballet have been enthusiastically revisited and revalued, resulting in the international success of leading Cuban dance troupes such as the Habana- based Conjunto Folklórico Nacional (p139 ) and the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. Much of Cuba’s best art is exhibited in apolitical genres such as pop art and opera, while more cutting-edge issues can be found in movies such as Fresa y Chocolate, a film that boldly questioned social mores and pushed homosexuality onto the public agenda. DANCE & THEATER Described by aficionados as ‘a vertical representation of a horizontal act,’ Cuban dancing is famous for its libidinous rhythms and sensuous moves. It comes as no surprise to discover that the country has produced some of the world’s most exciting dancers. With an innate musical rhythm at birth and the ability to replicate perfect salsa steps by the age of two or three, Cubans are natural performers who approach dance with a complete lack of self- consciousness – something that leaves most visitors from Europe or North America feeling as if they’ve got two left feet.