Ebola in the DRC - an Extraordinarily Complex Crisis I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dengue Fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing Events Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Crisis in Cameroon

Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme is currently monitoring 58 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key new and ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Hepatitis E in Central African Republic 3 - 5 New events Monkeypox in Central African Republic Dengue fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing events Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian crisis in Cameroon. 8 Summary of major issues challenges and For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health proposed actions measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 9 All events currently A table is provided at the end of the bulletin with information on all new and being monitored ongoing public health events currently being monitored in the region, as well as events that have recently been closed. Major issues and challenges include: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has reached a critical juncture, marked by a precarious security situation, persistence of pockets of community resistance/ mistrust and expanding geographical spread of the disease. During the reporting week, there was an incident involving a response team performing burial activity in Butembo. This came barely days following a widespread community strike (“ville morte”) in Beni and several towns, and an earlier armed attack in Beni. These incidents severely disrupted most outbreak control interventions. Meanwhile, EVD cases have been confirmed in new areas with worse insecurity and in close proximity to the border with Uganda. -

To Ebola Reston

WHO/HSE/EPR/2009.2 WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distin- guished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. This publication contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the World Health Organization. -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

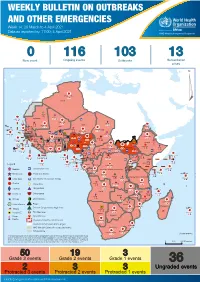

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 29 March to 4 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 4 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 116 103 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 117 622 3 105 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 420 164 Mauritania 7 2 10 501 392 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 927 449 Mali 3 334 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 595 165 Eritrea Cape Verde 38 520 1 037 Chad Senegal 4 918 185 59 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 17 125 159 9 761 45 Guinea-Bissau 796 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 225 46 215 189 2 963 0 162 593 2 048 Guinea 12 817 150 12 38 397 1 3 662 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 71 0 Ethiopia 420 14 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 53 920 779 52 14 Ghana 5 245 72 Côte d'Ivoire 10 098 108 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 25 0 19 670 120 43 180 237 90 287 740 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 138 988 2 224 1 952 87 655 2 51 22 43 0 112 12 6 1 488 6 3 988 79 11 187 6 902 102 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 042 85 41 016 335 Kenya Legend 7 100 90 Gabon Congo 18 504 301 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 212 34 22 482 311 Measles 18 777 111 Democratic Republic of the Congo 9 681 135 Burundi 2 964 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 27 930 739 1 525 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 189 0 4 084 20 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 22 631 542 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 88 930 1 220 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 661 1 123 862 0 3 719 146 -

Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical Presentation

Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical Presentation This lecture is on Ebola virus disease (EVD) and clinical care. This is part one of a three-part lecture on this topic. Preparing Healthcare Workers to Work in Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) in Africa This lecture will focus on EVD in the West African setting. Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care: The training and information you receive in this course will Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical not cover the use of certain interventions such as intubation Presentation or dialysis which are not available in West African Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs). You will need supplemental training This presentation is current as of December 2014. This presentation contains materials from Centers for Disease Control and to care for patients appropriately in countries where advanced Prevention (CDC), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and World Health Organization (WHO). care is available. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Centers for Disease Control and Prevention version 12.03.2014 The learning objectives for this lecture are to: Learning Objectives ▶ Describe the routes of Ebola virus transmission Describe the routes of Ebola virus transmission Explain when and how patients are infectious ▶ Explain when and how patients are infectious Describe the clinical features of patients with Ebola ▶ Describe screening criteria for Ebola virus disease Describe the clinical features of patients with Ebola (EVD) used in West Africa Explain how to identify patients with suspected ▶ Describe screening criteria for EVD used in West Africa EVD who present to the ETU ▶ Explain how to identify patients with suspected EVD who present to the ETU This presentation contains materials from CDC, MSF, and WHO 2 A number of different viruses cause viral hemorrhagic fever. -

Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview

1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme (WHE) is currently monitoring 60 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Ebola virus disease outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo 3 - 6 Ongoing events Cholera in Burundi Cholera in Cameroon 7 Summary of major Yellow fever in Nigeria. issues challenges and proposed actions For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 8 All events currently being monitored Major issues and challenges include: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is in a critical phase as it enters its sixth month since the declaration of the outbreak. Despite the use of an effective vaccine, novel therapeutics as well as other EVD strategic interventions, the outbreak is persisting due to security challenges, pockets of community reluctance and inadequate infection prevention and control in some health facilities. Nevertheless, WHO and partners, under the government’s leadership, continue to respond to the EVD outbreak and remain committed to containing the outbreak. The Ministry of Health of Burundi has declared a new outbreak of cholera in the country. This outbreak, which is rapidly evolving, is particularly affecting people living in overcrowded areas, where sanitation conditions are precarious. Given that the risk factors for transmission of water-borne diseases are prevalent in the affected communities, there is a need to aggressively tackle this outbreak at its early stage using relevant sectors in order to avoid further spread. -

Understanding Ebola

Understanding Ebola With the arrival of Ebola in the United States, it's very easy to develop fears that the outbreak that has occurred in Africa will suddenly take shape in your state and local community. It's important to remember that unless you come in direct contact with someone who is infected with the disease, you and your family will remain safe. State and government agencies have been making preparations to address isolated cases of infection and stop the spread of the disease as soon as it has been positively identified. Every day, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is monitoring developments, testing for suspected cases and safeguarding our lives with updates on events and the distribution of educational resources. Learning more about Ebola and understanding how it's contracted and spread will help you put aside irrational concerns and control any fears you might have about Ebola severely impacting your life. Use the resources below to help keep yourself calm and focused during this unfortunate time. Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Ebola hemorrhagic fever (Ebola HF) is one of numerous Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers. It is a severe, often fatal disease in humans and nonhuman primates (such as monkeys, gorillas, and chimpanzees). Ebola HF is caused by infection with a virus of the family Filoviridae, genus Ebolavirus. When infection occurs, symptoms usually begin abruptly. The first Ebolavirus species was discovered in 1976 in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo near the Ebola River. Since then, outbreaks have appeared sporadically. There are five identified subspecies of Ebolavirus. -

Emergence of Monkeypox — West and Central Africa, 1970–2017

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Emergence of Monkeypox — West and Central Africa, 1970–2017 Kara N. Durski, MPH1; Andrea M. McCollum, PhD2; Yoshinori Nakazawa, PhD2; Brett W. Petersen, MD2; Mary G. Reynolds, PhD2; Sylvie Briand, MD, PhD1; Mamoudou Harouna Djingarey, MD3; Victoria Olson, PhD2; Inger K. Damon, MD, PhD2, Asheena Khalakdina, PhD1 The recent apparent increase in human monkeypox cases Monkeypox is a zoonotic orthopoxvirus with a similar dis- across a wide geographic area, the potential for further spread, ease presentation to smallpox in humans, with the additional and the lack of reliable surveillance have raised the level of distinguishing symptom of lymphdenopathy. After an initial concern for this emerging zoonosis. In November 2017, the febrile prodrome, a centrifugally distributed maculopapular World Health Organization (WHO), in collaboration with rash develops, with lesions often present on the palms of CDC, hosted an informal consultation on monkeypox with the hands and soles of the feet. The infection can last up to researchers, global health partners, ministries of health, and 4 weeks, until crusts separate and a fresh layer of skin is formed. orthopoxvirus experts to review and discuss human monkeypox Sequelae include secondary bacterial infections, respiratory in African countries where cases have been recently detected and distress, bronchopneumonia, gastrointestinal involvement, also identify components of surveillance and response that need dehydration, encephalitis, and ocular infections, which can improvement. Endemic human monkeypox has been reported result in permanent corneal scarring. No specific treatment for from more countries in the past decade than during the previ- a monkeypox virus infection currently exists, and patients are ous 40 years. -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Exacerbation of Ebola Outbreaks by Conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

The exacerbation of Ebola outbreaks by conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Chad R. Wellsa,1, Abhishek Pandeya,1, Martial L. Ndeffo Mbahb, Bernard-A. Gaüzèrec, Denis Malvyc,d,e, Burton H. Singerf,2, and Alison P. Galvania aCenter for Infectious Disease Modeling and Analysis, Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, CT 06520; bDepartment of Veterinary Integrative Biosciences, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; cCentre René Labusquière, Department of Tropical Medicine and Clinical International Health, University of Bordeaux, 33076 Bordeaux, France; dDepartment for Infectious and Tropical Diseases, University Hospital Centre of Bordeaux, 33075 Bordeaux, France; eINSERM 1219, University of Bordeaux, 33076 Bordeaux, France; and fEmerging Pathogens Institute, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32610 Contributed by Burton H. Singer, September 9, 2019 (sent for review August 14, 2019; reviewed by David Fisman and Seyed Moghadas) The interplay between civil unrest and disease transmission is not recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus–Zaire Ebola virus vaccine well understood. Violence targeting healthcare workers and Ebola (13). The vaccination campaign not only played an important treatment centers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) role in curtailing the epidemic expeditiously (14), it also facili- has been thwarting the case isolation, treatment, and vaccination tated public awareness of the disease and improved practice of efforts. The extent to which conflict impedes public health re- Ebola safety precautions (15). By contrast, the sociopolitical sponse and contributes to incidence has not previously been crisis in eastern DRC has hampered the contact tracing that is a evaluated. -

Ebola Virus Disease Outbreak in North Kivu, DRC, 2021

THREAT ASSESSMENT BRIEF Ebola virus disease outbreak in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2021 22 February 2021 Summary On 7 February 2021, an Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak was declared by the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in the North Kivu province in the eastern part of the country. As of 18 February 2021, four confirmed cases of EVD, including two deaths, have been reported in the Biena and Katwa health zones. The first known case of EVD of this current outbreak died on 4 February. Laboratory testing confirmed infection with Ebola virus. North Kivu Provincial health authorities are currently leading the response, supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the DRC Ministry of Health. So far more than 300 contacts have been identified and a vaccination campaign was started on 15 February 2021. These EVD cases are the first cases of the disease reported in North Kivu, DRC, since the tenth outbreak was declared over in June 2020. The ongoing outbreak may spread to other areas within DRC and/or in neighbouring countries. Risk assessed Overall, the current risk for European Union/European Economic Area EU/EEA citizens living in or travelling to affected areas in DRC is considered low, as while disease in unvaccinated people is severe and most EU/EEA citizens are not commonly vaccinated against the disease, there is a very low likelihood of infection of EU/EEA citizens in the DRC. The current risk for citizens in the EU/EEA is considered very low, as the likelihood of introduction and secondary transmission within the EU/EEA is very low. -

Ebola Virus Proteins

Lecture Overview • Structure Filoviridae & the Ebola Virus • Virus Replication Cycle – Protein Synthesis • Pathogenesis Presented by David Gerber Filoviridae Family Structure • Filo: from latin meaning threadlike1 • Pleimorphic, • Structurally & Genetically similar to Filamentous Rhabdoviridae and Paramyxoviridae • Striated • 80nm diameter • Two Genera: • 130-140,000nm long – Marburg-like virus • Enveloped – Ebola-like virus Genome Ebola Virus Proteins • GP- Transmembrane glycoprotein • NP- Nucleoprotein necessary for capsid assembly • VP24- Anti-viral inhibitor? • VP35- Inhibits IFN production • Negative Sense ssRNA • VP30- Transcription anti-terminator • Unsegmented • VP40- necessary for capsid assembly and budding • 7 proteins •L-Viral Polymerase • Gene overlap 1 Replication Cycle Replication cont. 2 1 Host Entry 2 Adsorption- Glycoprotein (GP1) binds 3 - Contact with infected bodily fluids cellular receptor - Mediated by cellular cofactors. i.e. folate receptor α - Enters through mucous membrane or - Mononuclear phagocytic cells & monocytes are directly into blood (needle stick) primary targets4 - No confirmed spreading of virus by 3 Endocytosis aerosol in nature -pH lowering in endosome -GP2 mediates membrane fusion; release of viral particle into cytoplasm Replication Cont. Ebola Glycoprotein 4 Protein Synthesis - requires viral polymerase (L) • GP1/GP2- transmembrane protein - VP30 anti-terminator allows transcription of genes downstream – Binding/Fusion from first gene (Ebola Only) - VP35 prevents anti-viral response to dsRNA -

Systematic Review of Important Viral Diseases in Africa in Light of the ‘One Health’ Concept

pathogens Article Systematic Review of Important Viral Diseases in Africa in Light of the ‘One Health’ Concept Ravendra P. Chauhan 1 , Zelalem G. Dessie 2,3 , Ayman Noreddin 4,5 and Mohamed E. El Zowalaty 4,6,7,* 1 School of Laboratory Medicine and Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4001, South Africa; [email protected] 2 School of Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4001, South Africa; [email protected] 3 Department of Statistics, College of Science, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar 6000, Ethiopia 4 Infectious Diseases and Anti-Infective Therapy Research Group, Sharjah Medical Research Institute and College of Pharmacy, University of Sharjah, Sharjah 27272, UAE; [email protected] 5 Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, University of California, Irvine, CA 92868, USA 6 Zoonosis Science Center, Department of Medical Biochemistry and Microbiology, Uppsala University, SE 75185 Uppsala, Sweden 7 Division of Virology, Department of Infectious Diseases and St. Jude Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance (CEIRS), St Jude Children Research Hospital, Memphis, TN 38105, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 17 February 2020; Accepted: 7 April 2020; Published: 20 April 2020 Abstract: Emerging and re-emerging viral diseases are of great public health concern. The recent emergence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) in December 2019 in China, which causes COVID-19 disease in humans, and its current spread to several countries, leading to the first pandemic in history to be caused by a coronavirus, highlights the significance of zoonotic viral diseases.