Haemorigic Fever Viruses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Taxonomic Update for Phylum Negarnaviricota (Riboviria: Orthornavirae), Including the Large Orders Bunyavirales and Mononegavirales

Archives of Virology https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-020-04731-2 VIROLOGY DIVISION NEWS 2020 taxonomic update for phylum Negarnaviricota (Riboviria: Orthornavirae), including the large orders Bunyavirales and Mononegavirales Jens H. Kuhn1 · Scott Adkins2 · Daniela Alioto3 · Sergey V. Alkhovsky4 · Gaya K. Amarasinghe5 · Simon J. Anthony6,7 · Tatjana Avšič‑Županc8 · María A. Ayllón9,10 · Justin Bahl11 · Anne Balkema‑Buschmann12 · Matthew J. Ballinger13 · Tomáš Bartonička14 · Christopher Basler15 · Sina Bavari16 · Martin Beer17 · Dennis A. Bente18 · Éric Bergeron19 · Brian H. Bird20 · Carol Blair21 · Kim R. Blasdell22 · Steven B. Bradfute23 · Rachel Breyta24 · Thomas Briese25 · Paul A. Brown26 · Ursula J. Buchholz27 · Michael J. Buchmeier28 · Alexander Bukreyev18,29 · Felicity Burt30 · Nihal Buzkan31 · Charles H. Calisher32 · Mengji Cao33,34 · Inmaculada Casas35 · John Chamberlain36 · Kartik Chandran37 · Rémi N. Charrel38 · Biao Chen39 · Michela Chiumenti40 · Il‑Ryong Choi41 · J. Christopher S. Clegg42 · Ian Crozier43 · John V. da Graça44 · Elena Dal Bó45 · Alberto M. R. Dávila46 · Juan Carlos de la Torre47 · Xavier de Lamballerie38 · Rik L. de Swart48 · Patrick L. Di Bello49 · Nicholas Di Paola50 · Francesco Di Serio40 · Ralf G. Dietzgen51 · Michele Digiaro52 · Valerian V. Dolja53 · Olga Dolnik54 · Michael A. Drebot55 · Jan Felix Drexler56 · Ralf Dürrwald57 · Lucie Dufkova58 · William G. Dundon59 · W. Paul Duprex60 · John M. Dye50 · Andrew J. Easton61 · Hideki Ebihara62 · Toufc Elbeaino63 · Koray Ergünay64 · Jorlan Fernandes195 · Anthony R. Fooks65 · Pierre B. H. Formenty66 · Leonie F. Forth17 · Ron A. M. Fouchier48 · Juliana Freitas‑Astúa67 · Selma Gago‑Zachert68,69 · George Fú Gāo70 · María Laura García71 · Adolfo García‑Sastre72 · Aura R. Garrison50 · Aiah Gbakima73 · Tracey Goldstein74 · Jean‑Paul J. Gonzalez75,76 · Anthony Grifths77 · Martin H. Groschup12 · Stephan Günther78 · Alexandro Guterres195 · Roy A. -

Dengue Fact Sheet

State of California California Department of Public Health Health and Human Services Agency Division of Communicable Disease Control Dengue Fact Sheet What is dengue? Dengue is a disease caused by any one of four closely related dengue viruses (DENV- 1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4). Where does dengue occur? Dengue occurs in many tropical and sub-tropical areas of the world, particularly sub- Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America. With the exception of Mexico, Puerto Rico, small areas in southern Texas and southern Florida, and some regions of Hawaii, dengue transmission does not occur in North America. Worldwide there are an estimated 50 to 100 million cases of dengue per year. How do people get dengue? People get dengue from the bite of an infected mosquito. The mosquito becomes infected when it bites a person who has dengue virus in their blood. It takes a week or more for the dengue organisms to mature in the mosquito; then the mosquito can transmit the virus to another person when it bites. Dengue is transmitted principally by Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) and Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger mosquito). These mosquitoes are not native to California, but infestations have been identified in multiple counties in California. Dengue virus cannot be transmitted from person to person. What are the symptoms of dengue? There are two types of illness that can result from infection with a dengue virus: dengue and severe dengue. The main symptoms of dengue are high fever, severe headache, severe pain behind the eyes, joint pain, muscle and bone pain, rash, bruising, and may include mild bleeding from the nose or mouth. -

X-Ray Structure of the Arenavirus Glycoprotein GP2 in Its Postfusion Hairpin Conformation

Corrections NEUROBIOLOGY Correction for “High-resolution structure of hair-cell tip links,” The authors note that Figure 3 appeared incorrectly. The by Bechara Kachar, Marianne Parakkal, Mauricio Kurc, Yi-dong corrected figure and its legend appear below. This error does not Zhao, and Peter G. Gillespie, which appeared in issue 24, affect the conclusions of the article. November 21, 2000, of Proc Natl Acad Sci USA (97:13336– 13341; 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13336). CORRECTIONS Fig. 3. Upper and lower attachments of the tip link. (A and B) Freeze-etch images of tip-link upper insertions in guinea pig cochlea (A) and (left to right) two from guinea pig cochlea, two from bullfrog sacculus, and two from guinea pig utriculus (B). Each example shows pronounced branching. (C and D) Freeze- etch images of the tip-link lower insertion in stereocilia from bullfrog sacculus (C) and guinea pig utriculus (D); multiple strands (arrows) arise from the stereociliary tip. (E) Freeze-fracture image of stereociliary tips from bullfrog sacculus; indentations at tips are indicated by arrows. (Scale bars: A = 100 nm, B = 25 nm; C–E = 100 nm.) www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1311228110 www.pnas.org PNAS | July 16, 2013 | vol. 110 | no. 29 | 12155–12156 Downloaded by guest on September 28, 2021 BIOCHEMISTRY BIOPHYSICS AND COMPUTATIONAL BIOLOGY, STATISTICS Correction for “X-ray structure of the arenavirus glycoprotein Correction for “Differential principal component analysis of GP2 in its postfusion hairpin conformation,” by Sébastien Igo- ChIP-seq,” by Hongkai Ji, Xia Li, Qian-fei Wang, and Yang net, Marie-Christine Vaney, Clemens Vonhrein, Gérard Bri- Ning, which appeared in issue 17, April 23, 2013, of Proc Natl cogne, Enrico A. -

Dengue and Yellow Fever

GBL42 11/27/03 4:02 PM Page 262 CHAPTER 42 Dengue and Yellow Fever Dengue, 262 Yellow fever, 265 Further reading, 266 While the most important viral haemorrhagic tor (Aedes aegypti) as well as reinfestation of this fevers numerically (dengue and yellow fever) are insect into Central and South America (it was transmitted exclusively by arthropods, other largely eradicated in the 1960s). Other factors arboviral haemorrhagic fevers (Crimean– include intercontinental transport of car tyres Congo and Rift Valley fevers) can also be trans- containing Aedes albopictus eggs, overcrowding mitted directly by body fluids. A third group of of refugee and urban populations and increasing haemorrhagic fever viruses (Lassa, Ebola, Mar- human travel. In hyperendemic areas of Asia, burg) are only transmitted directly, and are not disease is seen mainly in children. transmitted by arthropods at all. The directly Aedes mosquitoes are ‘peri-domestic’: they transmissible viral haemorrhagic fevers are dis- breed in collections of fresh water around the cussed in Chapter 41. house (e.g. water storage jars).They feed on hu- mans (anthrophilic), mainly by day, and feed re- peatedly on different hosts (enhancing their role Dengue as vectors). Dengue virus is numerically the most important Clinical features arbovirus infecting humans, with an estimated Dengue virus may cause a non-specific febrile 100 million cases per year and 2.5 billion people illness or asymptomatic infection, especially in at risk.There are four serotypes of dengue virus, young children. However, there are two main transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, and it is un- clinical dengue syndromes: dengue fever (DF) usual among arboviruses in that humans are the and dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF). -

MARBURG HEMORRHAGIC FEVER (Marburg HF)

MARBURG HEMORRHAGIC FEVER (Marburg HF) REPORTING INFORMATION • Class A: Report immediately via telephone the case or suspected case and/or a positive laboratory result to the local public health department where the patient resides. If patient residence is unknown, report immediately via telephone to the local public health department in which the reporting health care provider or laboratory is located. Local health departments should report immediately via telephone the case or suspected case and/or a positive laboratory result to the Ohio Department of Health (ODH). • Reporting Form(s) and/or Mechanism: o Immediately via telephone. o For local health departments, cases should also be entered into the Ohio Disease Reporting System (ODRS) within 24 hours of the initial telephone report to the ODH. • Key fields for ODRS reporting include: import status (whether the infection was travel-associated or Ohio-acquired), date of illness onset, and all the fields in the Epidemiology module. AGENT Marburg hemorrhagic fever is a rare, severe type of hemorrhagic fever which affects both humans and non-human primates. Caused by a genetically unique zoonotic RNA virus of the family Filoviridae, its recognition led to the creation of this virus family. The five species of Ebola virus are the only other known members of the family Filoviridae. Marburg virus was first recognized in 1967, when outbreaks of hemorrhagic fever occurred simultaneously in laboratories in Marburg and Frankfurt, Germany and in Belgrade, Yugoslavia (now Serbia). A total of 31 people became ill, including laboratory workers as well as several medical personnel and family members who had cared for them. -

Presentation

COMPLETE HEMORRHAGIC FEVER VIRUS INACTIVATION DURING LYSIS IN THE FILMARRAY BIOTHREAT-E ASSAY DEMONSTRATES THE BIOSAFETY OF THIS TEST. Olivier Ferraris (3), Françoise Gay-Andrieu (1), Marie Moroso (2), Fanny Jarjaval (3), Mark Miller (1), Christophe N. Peyrefitte (3) (1) bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France, (2) Fondation Mérieux, France (3) Unité de Virologie, Institut de recherche biomédicale des armées, Brétigny sur Orge, France Background : Viral hemorrhagic fevers (VHFs) are a group of illnesses caused by mainly five families of viruses namely Arenaviridae, Filoviridae , Bunyaviridae (Orthonairovirus genus ), Flaviviruses and Paramyxovirus (Henipavirus genus). The filovirus species known to cause disease in humans, Ebola virus (Zaire Ebolavirus), Sudan virus (Sudan Ebolavirus), Tai Forest virus (Tai Forest Ebolavirus), Bundibugyo virus (Bundibugyo Ebolavirus), and Marburg virus are restricted to Central Africa for 35 years, and spread to Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone in early 2014. Lassa fever is responsible for disease outbreaks across West Africa and in Southern Africa in 2008, with the identification of novel world arenavirus (Lujo virus). Henipavirus spread South Asia to Australia. CCHFv spread asia to south europa. They are transmitted from host reservoir by direct contacts or through vectors such as ticks bits. Working with VHF viruses, need a Biosafety Level 4 (BSL-4) laboratory, however during epidemics such observed with Ebola virus in 2014, the need to diagnose rapidly the patients raised the necessity to develop local laboratories These viruses represents a threat to healthcare workers and researches who manage infected diagnostic samples in laboratories. Aim : 1 Inactivation step An FilmArray Bio Thereat-E assay for detection of Hemorrhagic fever viruse Interfering substance HF virus + FA Lysis Buffer such as Ebola virus was developed to respond to Hemorrhagic fever virus 106 Ebola virus Whole blood + outbreak. -

Dengue Fever/Severe Dengue Fever/Chikungunya Fever! Report on Suspicion of Infection During Business Hours

Dengue Fever/Severe Dengue Fever/Chikungunya Fever! Report on suspicion of infection during business hours PROTOCOL CHECKLIST Enter available information into Merlin upon receipt of initial report Review background information on the disease (see Section 2), case definitions (see Section 3 for dengue and for chikungunya), and laboratory testing (see Section 4) Forward specimens to the Florida Department of Health (DOH) Bureau of Public Health Laboratories (BPHL) for confirmatory laboratory testing (as needed) Inform local mosquito control personnel of suspected chikungunya or dengue case as soon as possible (if applicable) Inform state Arbovirus Surveillance Coordinator on suspicion of locally acquired arbovirus infection Contact provider (see Section 5A) Interview case-patient Review disease facts (see Section 2) Mode of transmission Ask about exposure to relevant risk factors (see Section 5. Case Investigation) History of travel, outdoor activities, and mosquito bites two weeks prior to onset History of febrile illness or travel for household members or other close contacts in the month prior to onset History of previous arbovirus infection or vaccination (yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis) Provide education on transmission and prevention (see Section 6) Awareness of mosquito-borne diseases Drain standing water at least weekly to stop mosquitoes from multiplying Discard items that collect water and are not being used Cover skin with clothing or Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered repellent such as DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) Use permethrin on clothing (not skin) according to manufacturer’s directions Cover doors and windows with intact screens to keep mosquitoes out of the house Enter additional data obtained from interview into Merlin (see Section 5D) Arrange for a convalescent specimen to be taken (if necessary) Dengue/Chikungunya Guide to Surveillance and Investigation Dengue Fever/Severe Dengue/Chikungunya 1. -

Dengue Fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing Events Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Crisis in Cameroon

Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme is currently monitoring 58 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key new and ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Hepatitis E in Central African Republic 3 - 5 New events Monkeypox in Central African Republic Dengue fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing events Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian crisis in Cameroon. 8 Summary of major issues challenges and For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health proposed actions measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 9 All events currently A table is provided at the end of the bulletin with information on all new and being monitored ongoing public health events currently being monitored in the region, as well as events that have recently been closed. Major issues and challenges include: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has reached a critical juncture, marked by a precarious security situation, persistence of pockets of community resistance/ mistrust and expanding geographical spread of the disease. During the reporting week, there was an incident involving a response team performing burial activity in Butembo. This came barely days following a widespread community strike (“ville morte”) in Beni and several towns, and an earlier armed attack in Beni. These incidents severely disrupted most outbreak control interventions. Meanwhile, EVD cases have been confirmed in new areas with worse insecurity and in close proximity to the border with Uganda. -

1 Lujo Viral Hemorrhagic Fever: Considering Diagnostic Capacity And

1 Lujo Viral Hemorrhagic Fever: Considering Diagnostic Capacity and 2 Preparedness in the Wake of Recent Ebola and Zika Virus Outbreaks 3 4 Dr Edgar Simulundu1,, Prof Aaron S Mweene1, Dr Katendi Changula1, Dr Mwaka 5 Monze2, Dr Elizabeth Chizema3, Dr Peter Mwaba3, Prof Ayato Takada1,4,5, Prof 6 Guiseppe Ippolito6, Dr Francis Kasolo7, Prof Alimuddin Zumla8,9, Dr Matthew Bates 7 8,9,10* 8 9 1 Department of Disease Control, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zambia, 10 Lusaka, Zambia 11 2 University Teaching Hospital & National Virology Reference Laboratory, Lusaka, Zambia 12 3 Ministry of Health, Republic of Zambia 13 4 Division of Global Epidemiology, Hokkaido University Research Center for Zoonosis 14 Control, Sapporo, Japan 15 5 Global Institution for Collaborative Research and Education, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, 16 Japan 17 6 Lazzaro Spallanzani National Institute for Infectious Diseases, IRCCS, Rome, Italy 18 7 World Health Organization, WHO Africa, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo 19 8 Department of Infection, Division of Infection and Immunity, University College London, 20 U.K 21 9 University of Zambia – University College London Research & Training Programme 22 (www.unza-uclms.org), University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia 23 10 HerpeZ (www.herpez.org), University Teaching Hospital, Lusaka, Zambia 24 25 *Corresponding author: Dr. Matthew Bates 26 Address: UNZA-UCLMS Research & Training Programme, University Teaching Hospital, 27 Lusaka, Zambia, RW1X 1 28 Email: [email protected]; Phone: +260974044708 29 30 2 31 Abstract 32 Lujo virus is a novel old world arenavirus identified in Southern Africa in 2008 as the 33 cause of a viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) characterized by nosocomial transmission 34 with a high case fatality rate of 80% (4/5 cases). -

To Ebola Reston

WHO/HSE/EPR/2009.2 WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distin- guished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. This publication contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the World Health Organization. -

A Look Into Bunyavirales Genomes: Functions of Non-Structural (NS) Proteins

viruses Review A Look into Bunyavirales Genomes: Functions of Non-Structural (NS) Proteins Shanna S. Leventhal, Drew Wilson, Heinz Feldmann and David W. Hawman * Laboratory of Virology, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Division of Intramural Research, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Hamilton, MT 59840, USA; [email protected] (S.S.L.); [email protected] (D.W.); [email protected] (H.F.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-406-802-6120 Abstract: In 2016, the Bunyavirales order was established by the International Committee on Taxon- omy of Viruses (ICTV) to incorporate the increasing number of related viruses across 13 viral families. While diverse, four of the families (Peribunyaviridae, Nairoviridae, Hantaviridae, and Phenuiviridae) contain known human pathogens and share a similar tri-segmented, negative-sense RNA genomic organization. In addition to the nucleoprotein and envelope glycoproteins encoded by the small and medium segments, respectively, many of the viruses in these families also encode for non-structural (NS) NSs and NSm proteins. The NSs of Phenuiviridae is the most extensively studied as a host interferon antagonist, functioning through a variety of mechanisms seen throughout the other three families. In addition, functions impacting cellular apoptosis, chromatin organization, and transcrip- tional activities, to name a few, are possessed by NSs across the families. Peribunyaviridae, Nairoviridae, and Phenuiviridae also encode an NSm, although less extensively studied than NSs, that has roles in antagonizing immune responses, promoting viral assembly and infectivity, and even maintenance of infection in host mosquito vectors. Overall, the similar and divergent roles of NS proteins of these Citation: Leventhal, S.S.; Wilson, D.; human pathogenic Bunyavirales are of particular interest in understanding disease progression, viral Feldmann, H.; Hawman, D.W. -

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

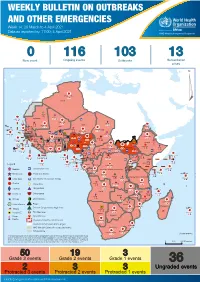

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 29 March to 4 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 4 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 116 103 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 117 622 3 105 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 420 164 Mauritania 7 2 10 501 392 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 927 449 Mali 3 334 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 595 165 Eritrea Cape Verde 38 520 1 037 Chad Senegal 4 918 185 59 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 17 125 159 9 761 45 Guinea-Bissau 796 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 225 46 215 189 2 963 0 162 593 2 048 Guinea 12 817 150 12 38 397 1 3 662 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 71 0 Ethiopia 420 14 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 53 920 779 52 14 Ghana 5 245 72 Côte d'Ivoire 10 098 108 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 25 0 19 670 120 43 180 237 90 287 740 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 138 988 2 224 1 952 87 655 2 51 22 43 0 112 12 6 1 488 6 3 988 79 11 187 6 902 102 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 042 85 41 016 335 Kenya Legend 7 100 90 Gabon Congo 18 504 301 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 212 34 22 482 311 Measles 18 777 111 Democratic Republic of the Congo 9 681 135 Burundi 2 964 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 27 930 739 1 525 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 189 0 4 084 20 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 22 631 542 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 88 930 1 220 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 661 1 123 862 0 3 719 146