Data Sharing in Public Health Emergencies- Yellow Fever And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Challenges and Opportunities for Innovation Peter Piot, London

Professor Peter Piot’ Biography Baron Peter Piot KCMG MD PhD is the Director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and the Handa Professor of Global Health. He was the founding Executive Director of UNAIDS and Under Secretary-General of the United Nations (1995-2008). A clinician and microbiologist by training, he co-discovered the Ebola virus in Zaire in 1976, and subsequently led pioneering research on HIV/AIDS, women’s health and infectious diseases in Africa. He has held academic positions at the Institute of Tropical Medicine, Antwerp; the University of Nairobi; the University of Washington, Seattle; Imperial College London, and the College de France, Paris, and was a Senior Fellow at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. He is a member of the US National Academy of Medicine, the National Academy of Medicine of France, and the Royal Academy of Medicine of his native Belgium, and is a fellow of the UK Academy of Medical Sciences and the Royal College of Physicians. He is a past president of the International AIDS Society and of the King Baudouin Foundation. In 1995 he was made a baron by King Albert II of Belgium, and in 2016 was awarded an honorary knighthood KCMG. Professor Piot has received numerous awards for his research and service, including the Canada Gairdner Global Health Award (2015), the Robert Koch Gold Medal (2015), the Prince Mahidol Award for Public Health (2014), and the Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize for Medical Research (2013), the F.Calderone Medal (2003), and was named a 2014 TIME Person of the Year (The Ebola Fighters). -

“If You Don't Find Anything, You Can't Eat” – Mining Livelihoods and Income, Gender Roles, and Food Choices In

Resources Policy 70 (2021) 101939 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Resources Policy journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/resourpol “If you don’t findanything, you can’t eat” – Mining livelihoods and income, gender roles, and food choices in northern Guinea Ronald Stokes-Walters a,d,*, Mohammed Lamine Fofana b, Joseph Lamil´e Songbono c, Alpha Oumar Barry c, Sadio Diallo c, Stella Nordhagen b,e, Laetitia X. Zhang a, Rolf D. Klemm a,b, Peter J. Winch a a Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health – 615 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD, 21205, USA b Helen Keller International – One Dag Hammarskjold Plaza, Floor 2, New York, NY, 10017, United States c Julius Nyerere University of Kankan, Kankan, Guinea d Action Against Hunger USA, One Whitehall St, Second Floor, New York NY, 10004, United States e Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN), Rue de Vermont 37-39, 1202, Geneva, Switzerland ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) continues to grow as a viable economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa. Artisanal mining The health and environmental impacts of the industry, notably linked to the use of potentially toxic chemicals, Food choice has been well documented. What has not been explored to the same extent is how pressures associated with ASM Women’s workload affect food choices of individuals and families living in mining camps. This paper presents research conducted in Income instability 18 mining sites in northern Guinea exploring food choices and the various factors affecting food decision-making Guinea practices. Two of the most influentialfactors to emerge from this study are income variability and gender roles. -

Dengue Fact Sheet

State of California California Department of Public Health Health and Human Services Agency Division of Communicable Disease Control Dengue Fact Sheet What is dengue? Dengue is a disease caused by any one of four closely related dengue viruses (DENV- 1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4). Where does dengue occur? Dengue occurs in many tropical and sub-tropical areas of the world, particularly sub- Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Central and South America. With the exception of Mexico, Puerto Rico, small areas in southern Texas and southern Florida, and some regions of Hawaii, dengue transmission does not occur in North America. Worldwide there are an estimated 50 to 100 million cases of dengue per year. How do people get dengue? People get dengue from the bite of an infected mosquito. The mosquito becomes infected when it bites a person who has dengue virus in their blood. It takes a week or more for the dengue organisms to mature in the mosquito; then the mosquito can transmit the virus to another person when it bites. Dengue is transmitted principally by Aedes aegypti (yellow fever mosquito) and Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger mosquito). These mosquitoes are not native to California, but infestations have been identified in multiple counties in California. Dengue virus cannot be transmitted from person to person. What are the symptoms of dengue? There are two types of illness that can result from infection with a dengue virus: dengue and severe dengue. The main symptoms of dengue are high fever, severe headache, severe pain behind the eyes, joint pain, muscle and bone pain, rash, bruising, and may include mild bleeding from the nose or mouth. -

Dengue and Yellow Fever

GBL42 11/27/03 4:02 PM Page 262 CHAPTER 42 Dengue and Yellow Fever Dengue, 262 Yellow fever, 265 Further reading, 266 While the most important viral haemorrhagic tor (Aedes aegypti) as well as reinfestation of this fevers numerically (dengue and yellow fever) are insect into Central and South America (it was transmitted exclusively by arthropods, other largely eradicated in the 1960s). Other factors arboviral haemorrhagic fevers (Crimean– include intercontinental transport of car tyres Congo and Rift Valley fevers) can also be trans- containing Aedes albopictus eggs, overcrowding mitted directly by body fluids. A third group of of refugee and urban populations and increasing haemorrhagic fever viruses (Lassa, Ebola, Mar- human travel. In hyperendemic areas of Asia, burg) are only transmitted directly, and are not disease is seen mainly in children. transmitted by arthropods at all. The directly Aedes mosquitoes are ‘peri-domestic’: they transmissible viral haemorrhagic fevers are dis- breed in collections of fresh water around the cussed in Chapter 41. house (e.g. water storage jars).They feed on hu- mans (anthrophilic), mainly by day, and feed re- peatedly on different hosts (enhancing their role Dengue as vectors). Dengue virus is numerically the most important Clinical features arbovirus infecting humans, with an estimated Dengue virus may cause a non-specific febrile 100 million cases per year and 2.5 billion people illness or asymptomatic infection, especially in at risk.There are four serotypes of dengue virus, young children. However, there are two main transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, and it is un- clinical dengue syndromes: dengue fever (DF) usual among arboviruses in that humans are the and dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF). -

International Congress on Targeting Ebola 28

CONFERENCE REPORT Journal of Virus Eradication 2015; 1: 282–283 International Congress on Targeting Ebola 28–29 May 2015, Pasteur Institute, Paris Sabine Kinloch-de Loës1* and Colin S Brown2,3 1 Division of Infection and Immunity, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK 2 Hospital for Tropical Diseases, University College Hospital London, UK 3 King‘s Sierra Leone Partnership, King‘s Centre for Global Health, King‘s Health Partners and King‘s College London, UK Introduction messages throughout the meeting. Professor Piot, one of the discoverers of the Ebola virus, described a recent return to The International Congress on Targeting Ebola 2015 was held on Yambuku in the DRC, the site of the first EVD outbreak in 1976. 28–29 May 2015 at the Pasteur Institute in Paris (www.targeting- The current state of the healthcare infrastructure did not reflect ebola.com). The meeting was organised in partnership with the the many promises of future investments made at the time of the COPED of the French Academy of Sciences, the French Task Force outbreak, a poignant reminder that we must not assume that Group for Ebola, the Pasteur Institute and the Task Force for current promises of investment will always materialise. Infectious Diseases. Publication of a summary of the meeting by the organisers is anticipated in an open-access journal. This paper Professor Muyembe-Tamfum, a microbiologist with four decades aims to provide a brief overview of the main discussion points of EVD experience, warned how outbreaks have become more during the meeting. frequent since 2012 in the DRC, both with the Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) strain now seen in West Africa, and the Bundibuyo ebolavirus This meeting brought together more than 300 experts in the field (BDBV). -

Dengue Fever/Severe Dengue Fever/Chikungunya Fever! Report on Suspicion of Infection During Business Hours

Dengue Fever/Severe Dengue Fever/Chikungunya Fever! Report on suspicion of infection during business hours PROTOCOL CHECKLIST Enter available information into Merlin upon receipt of initial report Review background information on the disease (see Section 2), case definitions (see Section 3 for dengue and for chikungunya), and laboratory testing (see Section 4) Forward specimens to the Florida Department of Health (DOH) Bureau of Public Health Laboratories (BPHL) for confirmatory laboratory testing (as needed) Inform local mosquito control personnel of suspected chikungunya or dengue case as soon as possible (if applicable) Inform state Arbovirus Surveillance Coordinator on suspicion of locally acquired arbovirus infection Contact provider (see Section 5A) Interview case-patient Review disease facts (see Section 2) Mode of transmission Ask about exposure to relevant risk factors (see Section 5. Case Investigation) History of travel, outdoor activities, and mosquito bites two weeks prior to onset History of febrile illness or travel for household members or other close contacts in the month prior to onset History of previous arbovirus infection or vaccination (yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis) Provide education on transmission and prevention (see Section 6) Awareness of mosquito-borne diseases Drain standing water at least weekly to stop mosquitoes from multiplying Discard items that collect water and are not being used Cover skin with clothing or Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered repellent such as DEET (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) Use permethrin on clothing (not skin) according to manufacturer’s directions Cover doors and windows with intact screens to keep mosquitoes out of the house Enter additional data obtained from interview into Merlin (see Section 5D) Arrange for a convalescent specimen to be taken (if necessary) Dengue/Chikungunya Guide to Surveillance and Investigation Dengue Fever/Severe Dengue/Chikungunya 1. -

Dengue Fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing Events Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Crisis in Cameroon

Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme is currently monitoring 58 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key new and ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Hepatitis E in Central African Republic 3 - 5 New events Monkeypox in Central African Republic Dengue fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing events Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian crisis in Cameroon. 8 Summary of major issues challenges and For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health proposed actions measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 9 All events currently A table is provided at the end of the bulletin with information on all new and being monitored ongoing public health events currently being monitored in the region, as well as events that have recently been closed. Major issues and challenges include: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has reached a critical juncture, marked by a precarious security situation, persistence of pockets of community resistance/ mistrust and expanding geographical spread of the disease. During the reporting week, there was an incident involving a response team performing burial activity in Butembo. This came barely days following a widespread community strike (“ville morte”) in Beni and several towns, and an earlier armed attack in Beni. These incidents severely disrupted most outbreak control interventions. Meanwhile, EVD cases have been confirmed in new areas with worse insecurity and in close proximity to the border with Uganda. -

To Ebola Reston

WHO/HSE/EPR/2009.2 WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distin- guished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. This publication contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the World Health Organization. -

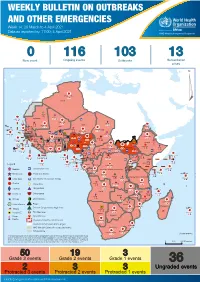

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 29 March to 4 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 4 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 116 103 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 117 622 3 105 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 420 164 Mauritania 7 2 10 501 392 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 927 449 Mali 3 334 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 595 165 Eritrea Cape Verde 38 520 1 037 Chad Senegal 4 918 185 59 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 17 125 159 9 761 45 Guinea-Bissau 796 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 225 46 215 189 2 963 0 162 593 2 048 Guinea 12 817 150 12 38 397 1 3 662 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 71 0 Ethiopia 420 14 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 53 920 779 52 14 Ghana 5 245 72 Côte d'Ivoire 10 098 108 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 25 0 19 670 120 43 180 237 90 287 740 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 138 988 2 224 1 952 87 655 2 51 22 43 0 112 12 6 1 488 6 3 988 79 11 187 6 902 102 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 042 85 41 016 335 Kenya Legend 7 100 90 Gabon Congo 18 504 301 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 212 34 22 482 311 Measles 18 777 111 Democratic Republic of the Congo 9 681 135 Burundi 2 964 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 27 930 739 1 525 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 189 0 4 084 20 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 22 631 542 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 88 930 1 220 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 661 1 123 862 0 3 719 146 -

Responding to the Ebola Epidemic in West Africa: What Role Does Religion Play? Case Study

WFDD CASE STUDY RESPONDING TO THE EBOLA EPIDEMIC IN WEST AFRICA: WHAT ROLE DOES RELIGION PLAY? By Katherine Marshall THE 2014 EBOLA EPIDEMIC was a human and a medical drama that killed more than 11,000 people and, still more, devastated the communities concerned and set back the development of health systems. Its impact was concentrated on three poor, fragile West African countries, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, but the tremors reverberated throughout the world, gen- erating reactions of compassion and fear, spurring mobilization of vast hu- man and financial resources, and inspiring many reflections on the lessons that should be learned by the many actors concerned. Among the actors were many with religious affiliations, who played distinctive roles at various points and across different sectors. This case study is one of a series produced by the Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs at Georgetown University and the World Faiths De- velopment Dialogue (WFDD), an NGO established in the World Bank and based today at Georgetown University. The goal is to generate relevant and demanding teaching materials that highlight ethical, cultural, and religious dimensions of contemporary international development topics. This case study highlights the complex institutional roles of religious actors and posi- tive and less positive aspects of their involvement, and, notably, how poorly prepared international organizations proved in engaging them in a systematic fashion. An earlier case study on Female Genital Cutting (FGC or FGM) focuses on the complex questions of how culture and religious beliefs influ- ence behaviors. This case was prepared under the leadership of Katherine Marshall and Crys- tal Corman. -

Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical Presentation

Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical Presentation This lecture is on Ebola virus disease (EVD) and clinical care. This is part one of a three-part lecture on this topic. Preparing Healthcare Workers to Work in Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) in Africa This lecture will focus on EVD in the West African setting. Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care: The training and information you receive in this course will Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical not cover the use of certain interventions such as intubation Presentation or dialysis which are not available in West African Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs). You will need supplemental training This presentation is current as of December 2014. This presentation contains materials from Centers for Disease Control and to care for patients appropriately in countries where advanced Prevention (CDC), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and World Health Organization (WHO). care is available. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Centers for Disease Control and Prevention version 12.03.2014 The learning objectives for this lecture are to: Learning Objectives ▶ Describe the routes of Ebola virus transmission Describe the routes of Ebola virus transmission Explain when and how patients are infectious ▶ Explain when and how patients are infectious Describe the clinical features of patients with Ebola ▶ Describe screening criteria for Ebola virus disease Describe the clinical features of patients with Ebola (EVD) used in West Africa Explain how to identify patients with suspected ▶ Describe screening criteria for EVD used in West Africa EVD who present to the ETU ▶ Explain how to identify patients with suspected EVD who present to the ETU This presentation contains materials from CDC, MSF, and WHO 2 A number of different viruses cause viral hemorrhagic fever. -

Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview

1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme (WHE) is currently monitoring 60 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Ebola virus disease outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo 3 - 6 Ongoing events Cholera in Burundi Cholera in Cameroon 7 Summary of major Yellow fever in Nigeria. issues challenges and proposed actions For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 8 All events currently being monitored Major issues and challenges include: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is in a critical phase as it enters its sixth month since the declaration of the outbreak. Despite the use of an effective vaccine, novel therapeutics as well as other EVD strategic interventions, the outbreak is persisting due to security challenges, pockets of community reluctance and inadequate infection prevention and control in some health facilities. Nevertheless, WHO and partners, under the government’s leadership, continue to respond to the EVD outbreak and remain committed to containing the outbreak. The Ministry of Health of Burundi has declared a new outbreak of cholera in the country. This outbreak, which is rapidly evolving, is particularly affecting people living in overcrowded areas, where sanitation conditions are precarious. Given that the risk factors for transmission of water-borne diseases are prevalent in the affected communities, there is a need to aggressively tackle this outbreak at its early stage using relevant sectors in order to avoid further spread.