Ebola Reston)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebola Virus Disease

Outbreaks Chronology: Ebola Virus Disease Known Cases and Outbreaks of Ebola Virus Disease, in Reverse Chronological Order: Reported number (%) of Reported deaths Ebola number of among Year(s) Country subtype human cases cases Situation August- Democratic Ebola virus 66 49 (74%) Outbreak occurred in November 2014 Republic of multiple villages in the Congo the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The outbreak was unrelated to the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa. March 2014- Multiple Ebola virus 28652 11325 Outbreak across Present countries multiple countries in West Africa. Number of patients is constantly evolving due to the ongoing investigation. 32 November 2012- Uganda Sudan virus 6* 3* (50%) Outbreak occurred in January 2013 the Luwero District. CDC assisted the Ministry of Health in the epidemiologic and diagnostic aspects of the outbreak. Testing of samples by CDC's Viral Special Pathogens Branch occurred at UVRI in Entebbe. 31 June-November Democratic Bundibugyo 36* 13* (36.1%) Outbreak occurred in 2012 Republic of virus DRC’s Province the Congo Orientale. Laboratory support was provided through CDC and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)’s field laboratory in Isiro, as well as through the CDC/UVRI lab in Uganda. The outbreak in DRC had no epidemiologic link to the near contemporaneous Ebola outbreak in the Kibaale district of Uganda. 31 June-October Uganda Sudan virus 11* 4* (36.4%) Outbreak occurred in 2012 the Kibaale District of Uganda. Laboratory tests of blood samples were conducted by the UVRI and the CDC. 31 May 2011 Uganda Sudan virus 1 1 (100%) The Uganda Ministry of Health informed the public a patient with suspected Ebola Hemorrhagic fever died on May 6, 2011 in the Luwero district, Uganda. -

Replication of Marburg Virus in Human Endothelial Cells a Possible Mechanism for the Development of Viral Hemorrhagic Disease

Replication of Marburg Virus in Human Endothelial Cells A Possible Mechanism for the Development of Viral Hemorrhagic Disease Hans-Joachim Schnittler,$ Friederike Mahner, * Detlev Drenckhahn, * Hans-Dieter Klenk, * and Heinz Feldmann * *Institut fir Virologie, Philipps-Universitdt Marburg, 3550 Marburg, Germany; tInstitutftirAnatomie, Universitdt Wiirzburg, 8700 Wiirzburg, Germany Abstract Rhabdoviridae, within the new proposed order Mononegavi- Marburg and Ebola virus, members of the family Filoviridae, rales (10). Virions are composed of a helical nucleocapsid cause a severe hemorrhagic disease in humans and primates. surrounded by a lipid envelope. The genome is nonsegmented, The disease is characterized as a pantropic virus infection often of negative sense, and 19 kb in length (3, 11, 12). Virion parti- resulting in a fulminating shock associated with hemorrhage, cles contain at least seven structural proteins (8, 13-16). and death. All known histological and pathophysiological pa- Filovirus infections have several pathological features in rameters of the disease are not sufficient to explain the devas- common with other severe viral hemorrhagic fevers such as tating symptoms. Previous studies suggested a nonspecific de- Lassa fever, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, and struction of the endothelium as a possible mechanism. Con- Dengue hemorrhagic fever (5). Among these viruses, filovi- cerning the important regulatory functions of the endothelium ruses cause the highest case-fatality rates ( - 35% for MBG [61 (blood pressure, antithrombogenicity, homeostasis), we exam- and up to 90% for EBO, subtype Zaire [17]) and the most ined Marburg virus replication in primary cultures of human severe hemorrhagic manifestations. The pathophysiologic endothelial cells and organ cultures of human umbilical cord events that make filovirus infections of humans so devastating veins. -

Comparison and Evaluation of Real-Time Taqman PCR for Detection and Quantification of Ebolavirus

viruses Article Comparison and Evaluation of Real-Time Taqman PCR for Detection and Quantification of Ebolavirus Yi Huang 1,* , Shuqi Xiao 2 and Zhiming Yuan 1,* 1 National Biosafety Laboratory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430020, China 2 Wuhan Institute of Virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430020, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (Y.H.); [email protected] (Z.Y.) Abstract: Given that ebolavirus causes severe and frequently lethal disease, its rapid and accurate detection using available and validated methods is essential for controlling infection. Real-time reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) has proven to be an invaluable tool for ebolaviruses diagnostics. Many assays with different targets have been developed, but they have not been externally compared or validated, and limits of detection are not uniformly reported. Here we compared and evaluated the sensitivity, reproducibility and specificity of 23 in-house assays under the same conditions. Our results showed that these assays were highly gene- and species- specific when evaluated using in vitro RNA transcripts and viral RNA, and the potential limits of detection were uniformly reported 2 6 ranging from 10 to 10 in vitro synthesized RNA transcripts copies perµL and 1–100 TCID50/mL. The comparison of these assays indicated that those targeting the more conservative NP gene could be the better option for EVD case definition and quantitative measurement because of its higher sensitivity for the same species. Our analysis could contribute to the standardization of ebolavirus detection and quantification assays, which can offer a better understanding of the meaning of results across laboratories and time points, as well as make them easy to implement, especially under outbreak conditions. -

Dengue Fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing Events Ebola Virus Disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian Crisis in Cameroon

Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme is currently monitoring 58 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key new and ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Hepatitis E in Central African Republic 3 - 5 New events Monkeypox in Central African Republic Dengue fever in Senegal 6 - 7 Ongoing events Ebola virus disease in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Humanitarian crisis in Cameroon. 8 Summary of major issues challenges and For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health proposed actions measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 9 All events currently A table is provided at the end of the bulletin with information on all new and being monitored ongoing public health events currently being monitored in the region, as well as events that have recently been closed. Major issues and challenges include: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo has reached a critical juncture, marked by a precarious security situation, persistence of pockets of community resistance/ mistrust and expanding geographical spread of the disease. During the reporting week, there was an incident involving a response team performing burial activity in Butembo. This came barely days following a widespread community strike (“ville morte”) in Beni and several towns, and an earlier armed attack in Beni. These incidents severely disrupted most outbreak control interventions. Meanwhile, EVD cases have been confirmed in new areas with worse insecurity and in close proximity to the border with Uganda. -

Biomarker Correlates of Survival in Pediatric Patients with Ebola Virus Disease

Emerging Infectious Diseases. Volume 20, Number 10—October 2014 CDC EID journal Ahead of Print / In Press Research Biomarker Correlates of Survival in Pediatric Patients with Ebola Virus Disease Anita K. McElroy , Bobbie R. Erickson, Timothy D. Flietstra, Pierre E. Rollin, Stuart T. Nichol, Jonathan S. Towner, and Christina F. Spiropoulou Author affiliations: Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, USA (A.K. McElroy); Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta (A.K. McElroy, B.R. Erickson, T.D. Flietstra, P.E. Rollin, S.T. Nichol, J.S. Towner, C.F. Spiropoulou) Suggested citation for this article Abstract Outbreaks of Ebola virus disease (EVD) occur sporadically in Africa and are associated with high case-fatality rates. Historically, children have been less affected than adults. The 2000–2001 Sudan virus–associated EVD outbreak in the Gulu district of Uganda resulted in 55 pediatric and 161 adult laboratory-confirmed cases. We used a series of multiplex assays to measure the concentrations of 55 serum analytes in specimens from patients from that outbreak to identify biomarkers specific to pediatric disease. Pediatric patients who survived had higher levels of the chemokine regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted marker and lower levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule, and soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule than did pediatric patients who died. Adult patients had similar levels of these analytes regardless of outcome. Our findings suggest that children with EVD may benefit from different treatment regimens than those for adults. Outbreaks of Ebola virus disease (EVD) occur sporadically in sub-Saharan Africa and are associated with exceptionally high case-fatality rates (CFRs). -

To Ebola Reston

WHO/HSE/EPR/2009.2 WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 EPIDEMIC AND PANDEMIC ALERT AND RESPONSE WHO experts consultation on Ebola Reston pathogenicity in humans Geneva, Switzerland 1 April 2009 © World Health Organization 2009 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distin- guished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. This publication contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the policies of the World Health Organization. -

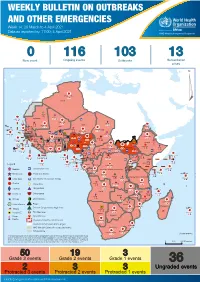

Weekly Bulletin on Outbreaks

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 14: 29 March to 4 April 2021 Data as reported by: 17:00; 4 April 2021 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 0 116 103 13 New event Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 117 622 3 105 Algeria ¤ 36 13 110 0 5 420 164 Mauritania 7 2 10 501 392 110 0 7 0 Niger 17 927 449 Mali 3 334 10 567 0 6 0 2 079 4 4 595 165 Eritrea Cape Verde 38 520 1 037 Chad Senegal 4 918 185 59 0 Gambia 27 0 3 0 17 125 159 9 761 45 Guinea-Bissau 796 17 7 0 Burkina Faso 225 46 215 189 2 963 0 162 593 2 048 Guinea 12 817 150 12 38 397 1 3 662 66 1 1 23 12 Benin 30 0 Nigeria 1 873 71 0 Ethiopia 420 14 481 5 6 188 15 Sierra Leone Togo 3 473 296 53 920 779 52 14 Ghana 5 245 72 Côte d'Ivoire 10 098 108 14 484 479 63 0 40 0 Liberia 17 0 South Sudan Central African Republic 916 2 45 0 25 0 19 670 120 43 180 237 90 287 740 Cameroon 7 0 28 676 137 5 330 13 138 988 2 224 1 952 87 655 2 51 22 43 0 112 12 6 1 488 6 3 988 79 11 187 6 902 102 Equatorial Guinea Uganda 542 8 Sao Tome and Principe 32 11 2 042 85 41 016 335 Kenya Legend 7 100 90 Gabon Congo 18 504 301 Rwanda Humanitarian crisis 2 212 34 22 482 311 Measles 18 777 111 Democratic Republic of the Congo 9 681 135 Burundi 2 964 6 Monkeypox Ebola virus disease Seychelles 27 930 739 1 525 0 420 29 United Republic of Tanzania Lassa fever Skin disease of unknown etiology 189 0 4 084 20 509 21 Cholera Yellow fever 1 349 5 6 257 229 22 631 542 cVDPV2 Dengue fever 88 930 1 220 Comoros Angola Malawi COVID-19 Chikungunya 33 661 1 123 862 0 3 719 146 -

Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical Presentation

Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical Presentation This lecture is on Ebola virus disease (EVD) and clinical care. This is part one of a three-part lecture on this topic. Preparing Healthcare Workers to Work in Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) in Africa This lecture will focus on EVD in the West African setting. Ebola Virus Disease and Clinical Care: The training and information you receive in this course will Part I: History, Transmission, and Clinical not cover the use of certain interventions such as intubation Presentation or dialysis which are not available in West African Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs). You will need supplemental training This presentation is current as of December 2014. This presentation contains materials from Centers for Disease Control and to care for patients appropriately in countries where advanced Prevention (CDC), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and World Health Organization (WHO). care is available. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Centers for Disease Control and Prevention version 12.03.2014 The learning objectives for this lecture are to: Learning Objectives ▶ Describe the routes of Ebola virus transmission Describe the routes of Ebola virus transmission Explain when and how patients are infectious ▶ Explain when and how patients are infectious Describe the clinical features of patients with Ebola ▶ Describe screening criteria for Ebola virus disease Describe the clinical features of patients with Ebola (EVD) used in West Africa Explain how to identify patients with suspected ▶ Describe screening criteria for EVD used in West Africa EVD who present to the ETU ▶ Explain how to identify patients with suspected EVD who present to the ETU This presentation contains materials from CDC, MSF, and WHO 2 A number of different viruses cause viral hemorrhagic fever. -

Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview

1 Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Health Emergency Information and Risk Assessment Overview Contents This Weekly Bulletin focuses on selected acute public health emergencies occurring in the WHO African Region. The WHO Health Emergencies Programme (WHE) is currently monitoring 60 events in the region. This week’s edition covers key ongoing events, including: 2 Overview Ebola virus disease outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo 3 - 6 Ongoing events Cholera in Burundi Cholera in Cameroon 7 Summary of major Yellow fever in Nigeria. issues challenges and proposed actions For each of these events, a brief description, followed by public health measures implemented and an interpretation of the situation is provided. 8 All events currently being monitored Major issues and challenges include: The Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is in a critical phase as it enters its sixth month since the declaration of the outbreak. Despite the use of an effective vaccine, novel therapeutics as well as other EVD strategic interventions, the outbreak is persisting due to security challenges, pockets of community reluctance and inadequate infection prevention and control in some health facilities. Nevertheless, WHO and partners, under the government’s leadership, continue to respond to the EVD outbreak and remain committed to containing the outbreak. The Ministry of Health of Burundi has declared a new outbreak of cholera in the country. This outbreak, which is rapidly evolving, is particularly affecting people living in overcrowded areas, where sanitation conditions are precarious. Given that the risk factors for transmission of water-borne diseases are prevalent in the affected communities, there is a need to aggressively tackle this outbreak at its early stage using relevant sectors in order to avoid further spread. -

Understanding Ebola

Understanding Ebola With the arrival of Ebola in the United States, it's very easy to develop fears that the outbreak that has occurred in Africa will suddenly take shape in your state and local community. It's important to remember that unless you come in direct contact with someone who is infected with the disease, you and your family will remain safe. State and government agencies have been making preparations to address isolated cases of infection and stop the spread of the disease as soon as it has been positively identified. Every day, the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is monitoring developments, testing for suspected cases and safeguarding our lives with updates on events and the distribution of educational resources. Learning more about Ebola and understanding how it's contracted and spread will help you put aside irrational concerns and control any fears you might have about Ebola severely impacting your life. Use the resources below to help keep yourself calm and focused during this unfortunate time. Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever Ebola hemorrhagic fever (Ebola HF) is one of numerous Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers. It is a severe, often fatal disease in humans and nonhuman primates (such as monkeys, gorillas, and chimpanzees). Ebola HF is caused by infection with a virus of the family Filoviridae, genus Ebolavirus. When infection occurs, symptoms usually begin abruptly. The first Ebolavirus species was discovered in 1976 in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo near the Ebola River. Since then, outbreaks have appeared sporadically. There are five identified subspecies of Ebolavirus. -

Emergence of Monkeypox — West and Central Africa, 1970–2017

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Emergence of Monkeypox — West and Central Africa, 1970–2017 Kara N. Durski, MPH1; Andrea M. McCollum, PhD2; Yoshinori Nakazawa, PhD2; Brett W. Petersen, MD2; Mary G. Reynolds, PhD2; Sylvie Briand, MD, PhD1; Mamoudou Harouna Djingarey, MD3; Victoria Olson, PhD2; Inger K. Damon, MD, PhD2, Asheena Khalakdina, PhD1 The recent apparent increase in human monkeypox cases Monkeypox is a zoonotic orthopoxvirus with a similar dis- across a wide geographic area, the potential for further spread, ease presentation to smallpox in humans, with the additional and the lack of reliable surveillance have raised the level of distinguishing symptom of lymphdenopathy. After an initial concern for this emerging zoonosis. In November 2017, the febrile prodrome, a centrifugally distributed maculopapular World Health Organization (WHO), in collaboration with rash develops, with lesions often present on the palms of CDC, hosted an informal consultation on monkeypox with the hands and soles of the feet. The infection can last up to researchers, global health partners, ministries of health, and 4 weeks, until crusts separate and a fresh layer of skin is formed. orthopoxvirus experts to review and discuss human monkeypox Sequelae include secondary bacterial infections, respiratory in African countries where cases have been recently detected and distress, bronchopneumonia, gastrointestinal involvement, also identify components of surveillance and response that need dehydration, encephalitis, and ocular infections, which can improvement. Endemic human monkeypox has been reported result in permanent corneal scarring. No specific treatment for from more countries in the past decade than during the previ- a monkeypox virus infection currently exists, and patients are ous 40 years. -

WHO's Response to the 2018–2019 Ebola Outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo

WHO's response to the 2018–2019 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu and Ituri, the Democratic Republic of the Congo Report to donors for the period August 2018 – June 2019 2 | 2018-2019 North Kivu and Ituri Ebola virus disease outbreak: WHO report to donors © World Health Organization 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.