Development of Natural Language Processing Tools for Cook Islands Maori¯

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

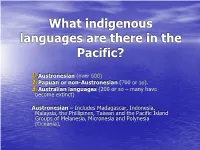

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

The Phonemic Reality of Polynesian Vowel Length

The Phonetic Nature of Niuean * Vowel Length Nicholas Rolle University of Toronto In this paper, I argue that in Niuean, long vowels are underlying sequences of two qualitatively identical vowels, extending an analysis laid out in Taumoefolau (2002) on the related Tongic language Tongan. She argues that a long vowel will result predictably when stress falls on the first element of a double monophthong vowel sequence. Thus vowel length in these languages is a phonetic, not phonological, phenomenon. This account for vowel length is worked into an Optimality Theory (OT) framework, which crucially constrains RH- CONTOUR and ALL-FT-RIGHT above a constraint against double articulation, DIST(INCT). In addition, I provide a review of the literature concerning vowel length across Polynesian languages, and conclude that this analysis cannot be extended to all members of the Polynesian language family. 1. Introduction Across Polynesian languages, the presence of long vowels is uncontroversial, though whether these are only surface long vowels (i.e. phonetic) or underlying long vowels (i.e. phonemic) remains a contentious topic. In this paper, I outline an analysis of Tongan long vowels laid out in Taumoefolau (2002), and later supported by Anderson & Otsuka (2006), and extend this analysis to the related Tongic language Niuean. It is argued in Taumoefolau (2002) that Tongan long vowels are underlying identical vowel-vowel sequences (/ViVi/), whose surface manifestation is predictably a long vowel if stress falls on the first vowel of this sequence, and a double articulated vowel if stress falls on the second. This analysis is laid out in detail in section 3, preceded by a section describing some basic facts of Tongan phonology, and a review of the previous analyses of Tongan vowel length. -

Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori O Te Pae Tonga O Te Kuki Airani Also Known As Southern Cook Islands Māori

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. Editors: Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori SALLY AKEVAI NICHOLAS Cite this article: Sally Akevai Nicholas (2018). Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori. In Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. London: EL Publishing. pp. 36-64 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/160 This electronic version first published: July 2018 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori Sally Akevai Nicholas School of Language & Culture, Auckland University of Technology Language Name: Southern Cook Islands Māori Language Family: East Polynesian, Polynesian, Oceanic, Austronesian ISO 639-3 Code: rar Glottolog Code: raro1241 Number of speakers: ~15,000 - 20,2001 Location: 8-23S, 156-167W Vitality rating: EGIDS between 7 (shifting) and 8a (moribund) 1. -

Making a Case for Tongan As an Endangered Language

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Making a Case for Tongan as an provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Endangered Language Yuko Otsuka At fi rst glance, Tongan appears far from being endangered. It has nearly 100,000 speakers—remarkably sizable compared to other languages of Oceania—and is spoken in a predominantly monolingual and monocul- tural society.1 Furthermore, Tonga is an independent nation-state, in fact, the last kingdom in Polynesia. Why should one be talking at all about Tongan being endangered? This paper examines the linguistic situation in Tonga and argues that there are reasons to be concerned about the future of the Tongan language in the long run. The position put forward in this paper is as follows: In the postcolonial context, many instances of language endangerment should be defi ned in terms of a unit larger than a nation-state. Globalization has put small island nations like Tonga in a position such that, in order to survive, they are compelled to conform to the Western development model that is asso- ciated with English as a socioeconomically privileged language. Here, the term “globalization” refers to a particular aspect of the phenomenon, that is, interconnectedness facilitated by the expansion of Euro-American values. Interconnectedness certainly has benefi cial consequences, such as bringing new opportunities. Epeli Hau‘ofa, for example, has argued that it has empowered the peoples of Oceania, liberating them from the artifi cial boundaries imposed by nineteenth-century imperialism (1993, 10). The following discussion, however, focuses on the adverse effects of intercon- nectedness, especially as it affects language maintenance. -

The Language of Rapa Iti: Description of a Language in Change

THE LANGUAGE OF RAPA ITI: DESCRIPTION OF A LANGUAGE IN CHANGE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2015 By Mary E. Walworth Dissertation Committee: Yuko Otsuka, Chairperson Robert Blust Katie Drager Ken Rehg Terry Hunt Keywords: Rapa Iti, Polynesia, language change, language contact Dedicated to my god-daughter, Pākora, and to all of the other young people of Rapa Iti. You all are the reason I have done this project and I hope it serves you well. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What an adventure this dissertation has been - linguistically, professionally, and personally. This path began for me five years ago, when, somewhat randomly, I chose to study a language spoken in the most faraway place I could find in French Polynesia. I now know that this choice was not random at all, but a critical decision for my life. My friend Tākura once told me as we were looking out over Ahurei Bay one afternoon in Rapa, “there are many secrets here for you, I can't tell them to you, but I hope you will tell me when you find them out.” She was right - the secrets of language and of life that were revealed to me in Rapa are invaluable. They have changed me and my perceptions of the world. I am not the same researcher nor am I the same person that I was when I first arrived there. I met friends for life on that island, and my partner for life there. -

Loanword Strata in Rotuman

Loanword Strata in Rotuman by Hans Schmidt In Language Contacts in Prehistory: Studies in Stratigraphy: Papers from the Workshop on Linguistic Stratigraphy and Prehistory at the Fifteenth International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Melbourne, 17 August 2001, pp. 201-240 (2003). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Co. (c) 2003 John Benjamins Publishing Company. Not to be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. LOANWORD STRATA IN ROTUMAN Hans Schmidt University of the South Pacific, Vanuatu 1. Introduction Rotuma is a small island in the South Pacific.1 It lies roughly at the crossroads of Polynesia, Melanesia and Micronesia. Politically, the island forms part of the Republic of Fiji; though the closest Fijian island, Cikobia, is about 465 km distant (Woodhall 1987:1). The island is accessible from Suva, the capital of Fiji, by a two-day boat trip or in two hours by plane. In contrast to its Northern neighbor Tuvalu, Rotuma is not a coral atoll but a so called ‘high’ island of volcanic origin (Pleistocene), its surface area is 46 km2 and its soil is very fertile. Rotuma has a population of approximately 2,700 inhabitants who live in twenty villages scattered along the coast. This constitutes the highest population density (59 per km2) for all Fijian islands (Walsh 1982:20), although three quarters of the Rotumans have left their home island for the urban areas of Fiji or overseas. Many of these Fiji-Rotumans have never been on Rotuma or at most for a brief Christmas holiday. In contrast to its small number of speakers, Rotuman has featured frequently in works of general and comparative linguistics.2 What makes Rotuman so interesting in the eyes of linguists? Its productive metathesis. -

Eastern Polynesian: the Linguistic Evidence Revisited

W O R K I N G P A P E R S I N L I N G U I S T I C S The notes and articles in this series are progress reports on work being carried on by students and faculty in the Department. Because these papers are not finished products, readers are asked not to cite from them without noting their preliminary nature. The authors welcome any comments and suggestions that readers might offer. Volume 43(5) December 2012 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA HONOLULU 96822 An Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Institution Working Papers in Linguistics: University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Vol. 43(5) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS FACULTY 2012 Victoria B. Anderson Andrea Berez Derek Bickerton (Emeritus) Robert A. Blust Lyle Campbell Kenneth W. Cook (Adjunct) Kamil Deen Patricia J. Donegan (Co-Graduate Chair) Katie K. Drager Emanuel J. Drechsel (Adjunct) Michael L. Forman (Emeritus) John H. Haig (Adjunct) Roderick A. Jacobs (Emeritus) William O’Grady Yuko Otsuka Ann Marie Peters (Emeritus, Co-Graduate Chair) Kenneth L. Rehg (Chair) Lawrence A. Reid (Emeritus) Amy J. Schafer Albert J. Schütz, (Emeritus, Editor) Jacob Terrell ii EASTERN POLYNESIAN: THE LINGUISTIC EVIDENCE REVISITED MARY WALWORTH For the past forty years, historical linguistics and archaeology have provided seemingly mutually corroboratory evidence for the settlement of east Polynesia. However, recent findings in archaeology have shifted this relationship out of balance, calling previous conclusions into question.1 This paper first reviews the generally accepted archaeological and linguistic theories of east Polynesia's settlement, then describes the new archaeological findings, highlighting the areas where the evidence from the two disciplines is discordant. -

Interaction and Diversification in the Austronesian Colonization of Remote Oceania

For Workshop on Migration, Ile de Porquerolles, France, Sept. 5-7 2007 Why do Polynesian island groups have one language and Melanesian island groups have many? Patterns of interaction and diversification in the Austronesian colonization of Remote Oceania ANDREW PAWLEY AUSTRALIAN NATONAL UNIVERSITY 1. The puzzle of different language densities in Polynesia and Melanesia The islands and seas of the southwest and central Pacific are conveniently subsumed under the heading ‘Oceania’.1 In the anthropological and geographic literature Oceania is generally divided into three regions: Melanesia, Polynesia and Micronesia. This division, based on 19th century perceptions of racial and cultural groupings, is unsatisfactory especially because ‘Melanesia’ is not a coherent entity of the same order as the other two, but it remains a standard frame of reference. 2 The prehistoric human settlement of Oceania has left many complex and sometimes puzzling cultural, linguistic and biological patterns. This paper investigates one particular puzzle – the striking differences between Polynesia and Fiji, on the one hand, and almost all of Island Melanesia, on the other, in the density of languages per island group. (‘Island Melanesia’ is that part of Melanesia that excludes the 2400 km long island of New Guinea.) In Polynesia the norm is one language per island group; in Island Melanesia it is many languages. Thus, Samoa, Tonga, the Tokelaus, Tuvalu, the Southern Cooks, the Societies, the Marquesas and Tuamotus at first European contact each had a single language, generally with no more than modest regional variation. The large Fijian archipelago can be said to have just two distinct languages, though each ‘language’ is a dialect chain of considerable diversity. -

Can the Polynesian Languages Be Used in the Proceedings of the Assembly of French Polynesia?

127 CAN THE POLYNESIAN LANGUAGES BE USED IN THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE ASSEMBLY OF FRENCH POLYNESIA? Alain Moyrand* and Tony Angelo** In 2010 the European Court of Human Rights rejected a petition relating to the right to use a Polynesian language in the Assembly of French Polynesia. This article considers the relationship between the French Constitution and the Organic Law, relating to the status of French Polynesia, and the use of languages other than French in the proceedings of the Assembly of French Polynesia. The consequences of case law for the use of a Polynesian language in the Assembly of French Polynesia are also examined. The article concludes is that there is no right to use a Polynesian language in the French Polynesian Assembly, but that the use of Tahitian and other Polynesian languages is a long established practice of the Assembly and that their use in a number of limited cases does not render the proceedings in which they are used invalid. L'usage des langues polynésiennes ne constitue pas en l'état du droit constitutionnel français un droit politique, il n'a pour fondements que des droits culturels et reste inscrit comme tel dans la loi organique statutaire. Pour qu'il en aille autrement, il faudrait au préalable réviser la Constitution française. I INTRODUCTION After being a colonial protectorate of France from 1842 to 1880, the former Kingdom of Tahiti was annexed by France by Act of 30 December 1880 and established as a colony. Then just before World War Two the colony was transformed into a territorial entity. -

Loanwords in Hawaiian

Loanwords in Hawaiian ‘Oiwi¯ Parker Jones University of Oxford 1 The language and its speakers The Hawaiian language (i.e., ka ‘olelo¯ Hawai‘i) is indigenous to the islands of Hawai‘i. Until Western contact in 1778, Hawaiian was very likely the only language spoken throughout the archipelago. Hawaiian is an Austronesian language that belongs to the Eastern Polynesian language family and is closely related to Maori,¯ Marquesan, and Tahitian (see Figure1). PROTO-POLYNESIAN hVV hhhh VVVV hhhh VVVV hhhh VVV PROTO-TONGIC PROTO-NUCLEAR POLYNESIAN hVV hhhh VVVV hhhh VVVV hhhh VVV PROTO-SAMOIC OUTLIER PROTO-EASTERN POLYNESIAN hVV hhhh VVVV hhhh VVVV hhhh VVV PROTO-EASTER ISLAND PROTO-CENTRAL POLYNESIAN Tongan Samoan Rapa Nui Hawaiian etc. etc. Maori¯ Marquesan Tahitian etc. Figure 1: The Polynesian family tree (adapted from Pawley 1966, Clark 1979:258, and Schütz 1994:335) The archaeological evidence suggests that Polynesians may have first settled Hawai‘i as early as 200 CE (see, e.g., Kirch 1998:161). Yet to arrive in Hawai‘i from the Marque- sas or Tahiti, the early settlers had to cross over 2,000 miles of open ocean without the benefit of modern navigational instruments, such as a compass or a clock. According to Hawaiian oral history, this remarkable achievement was in fact repeated many times. Moreover, the modern revival of stellar navigation provides strong evidence that such long-distance commutes were practicable (Pi‘inai‘a¯ 1998). Although there is no accurate census or survey, Kapono(1998:199) estimates that there were about 5,000 Hawaiian speakers in 1995. Of these, 1,000 were manaleo¯ (i.e., ‘heritage speakers’ or ‘native-speaking elders’), 400 of whom had connections to the island of Ni‘ihau (see section3 below). -

Cook Island Maori English

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with with permission permission of the of copyright the copyright owner. owner.Further reproductionFurther reproduction prohibited without prohibited permission.