The Polynesian Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethnography of Ontong Java and Tasman Islands with Remarks Re: the Marqueen and Abgarris Islands

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 9, No. 3 July 1986 ETHNOGRAPHY OF ONTONG JAVA AND TASMAN ISLANDS WITH REMARKS RE: THE MARQUEEN AND ABGARRIS ISLANDS by R. Parkinson Translated by Rose S. Hartmann, M.D. Introduced and Annotated by Richard Feinberg Kent State University INTRODUCTION The Polynesian outliers for years have held a special place in Oceanic studies. They have figured prominently in discussions of Polynesian set- tlement from Thilenius (1902), Churchill (1911), and Rivers (1914) to Bayard (1976) and Kirch and Yen (1982). Scattered strategically through territory generally regarded as either Melanesian or Microne- sian, they illustrate to varying degrees a merging of elements from the three great Oceanic culture areas—thus potentially illuminating pro- cesses of cultural diffusion. And as small bits of land, remote from urban and administrative centers, they have only relatively recently experienced the sustained European contact that many decades earlier wreaked havoc with most islands of the “Polynesian Triangle.” The last of these characteristics has made the outliers particularly attractive to scholars interested in glimpsing Polynesian cultures and societies that have been but minimally influenced by Western ideas and Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 1 2 Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 accoutrements. For example, Tikopia and Anuta in the eastern Solo- mons are exceptional in having maintained their traditional social structures, including their hereditary chieftainships, almost entirely intact. And Papua New Guinea’s three Polynesian outliers—Nukuria, Nukumanu, and Takuu—may be the only Polynesian islands that still systematically prohibit Christian missionary activities while proudly maintaining important elements of their old religions. -

Reflexives Markers in Oceanic Languages

DGfS-CNRS Summer School: Linguistic Typology (3) Koenig/Moyse-Faurie Reflexives markers in Oceanic Languages Ekkehard König (FU Berlin) & Claire Moyse-Faurie (Lacito-CNRS) 1. Previous views 1.1. A lack of reflexive markers ? “[Oceanic languages] have morphological markers used to encode reciprocal and certain other situations, but not reflexive situations” (Lichtenberk, 2000:31). “Assuming that reflexivity is inherently related to transitivity, we understand why we do not find morphosyntactic reflexivisation in Samoan: Samoan does not have syntactically transitive clauses” (Mosel, 1991: ‘Where have all the Samoan reflexives gone?’) “There is no mark of reflexive, either in the form of a reflexive pronoun or of a reflexive marker on the verb – one simply says I saw me” (Dixon, 1988:9). Out of context, there are indeed many cases of ambiguity with 3rd persons, due to the frequent absence of obligatory grammaticalized constructions to express reflexivity: XÂRÂGURÈ (South of the Mainland, New Caledonia) (1) nyî xati nyî 3SG scold 3SG ‘He is scolding him/himself.’ NUMÈÈ (Far South of the Mainland, New Caledonia) (2) treâ trooke nê kwè nê ART.PL dog 3PL bite 3PL ‘The dogs are biting them/each other.’ MWOTLAP (North Central Vanuatu) (3) Kēy mu-wuh mat kēy 3PL PERF-hit die 3PL ‘They killed each other/themselves.’ (François, 2001:372) TOQABAQITA (South East Solomon) (4) Keero’a keko thathami keero’a 3DU 3DU like 3DU ‘They liked them/each other/themselves.’ (Lichtenberk, 1991:172) 1.2. Confusion between middle markers and reflexive markers “In East Futunan, the reflexive meaning is either lexicalised (i.e. expressed by lexically reflexive verbs) or by transitive verbs, the two arguments of which refer to the same entity. -

Existential and Locative Predication in Some Eastern Oceanic Languages Claire Moyse-Faurie

Existential and locative predication in some eastern Oceanic languages Claire Moyse-Faurie To cite this version: Claire Moyse-Faurie. Existential and locative predication in some eastern Oceanic languages. Te Reo: Journal of the New Zealand Society, Linguistic Society of New Zealand, 2019, Special Issue in Honour of Frantisek Lichtenberk, 62 (1). hal-02868639 HAL Id: hal-02868639 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02868639 Submitted on 19 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Te Reo the Journal of the Linguistic Society of New Zealand Volume 62 Issue 1 (Special Issue): Issue in Honour of Frantisek Lichtenberk Research Article 2019 pp. 49–74 September 2019 Existential and locative predication in some eastern Oceanic languages Claire Moyse-Faurie Lacito-CNRS, France This paper is a peer-reviewed contribution from https://nzlingsoc.makeitso.nz/journal/current-issue ©Te Reo – The Journal of the Linguistic Society of New Zealand Guest Editors: Andreea S. Calude & Suzanne Kemmer Claire Moyse-Faurie 49 Existential and locative predication in some eastern Oceanic languages Claire Moyse-Faurie Abstract In many Oceanic languages a category of plain verbs expressing existence, and their negative counterparts, is found. -

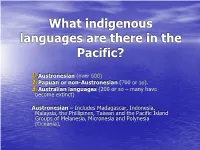

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

The Phonemic Reality of Polynesian Vowel Length

The Phonetic Nature of Niuean * Vowel Length Nicholas Rolle University of Toronto In this paper, I argue that in Niuean, long vowels are underlying sequences of two qualitatively identical vowels, extending an analysis laid out in Taumoefolau (2002) on the related Tongic language Tongan. She argues that a long vowel will result predictably when stress falls on the first element of a double monophthong vowel sequence. Thus vowel length in these languages is a phonetic, not phonological, phenomenon. This account for vowel length is worked into an Optimality Theory (OT) framework, which crucially constrains RH- CONTOUR and ALL-FT-RIGHT above a constraint against double articulation, DIST(INCT). In addition, I provide a review of the literature concerning vowel length across Polynesian languages, and conclude that this analysis cannot be extended to all members of the Polynesian language family. 1. Introduction Across Polynesian languages, the presence of long vowels is uncontroversial, though whether these are only surface long vowels (i.e. phonetic) or underlying long vowels (i.e. phonemic) remains a contentious topic. In this paper, I outline an analysis of Tongan long vowels laid out in Taumoefolau (2002), and later supported by Anderson & Otsuka (2006), and extend this analysis to the related Tongic language Niuean. It is argued in Taumoefolau (2002) that Tongan long vowels are underlying identical vowel-vowel sequences (/ViVi/), whose surface manifestation is predictably a long vowel if stress falls on the first vowel of this sequence, and a double articulated vowel if stress falls on the second. This analysis is laid out in detail in section 3, preceded by a section describing some basic facts of Tongan phonology, and a review of the previous analyses of Tongan vowel length. -

Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori O Te Pae Tonga O Te Kuki Airani Also Known As Southern Cook Islands Māori

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. Editors: Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori SALLY AKEVAI NICHOLAS Cite this article: Sally Akevai Nicholas (2018). Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori. In Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. London: EL Publishing. pp. 36-64 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/160 This electronic version first published: July 2018 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori Sally Akevai Nicholas School of Language & Culture, Auckland University of Technology Language Name: Southern Cook Islands Māori Language Family: East Polynesian, Polynesian, Oceanic, Austronesian ISO 639-3 Code: rar Glottolog Code: raro1241 Number of speakers: ~15,000 - 20,2001 Location: 8-23S, 156-167W Vitality rating: EGIDS between 7 (shifting) and 8a (moribund) 1. -

New Records of Butterflies (Lepidoptera) from the Eastern Caroline Islands, Micronesia1

New Records of Butterflies (Lepidoptera) from the Eastern Caroline Islands, Micronesia1 Donald W. Buden,2,5 Donald P. Sands,3 and W. John Tennent4 Abstract: Twenty-three new locality records are presented for nine species of butterflies (Lepidoptera) from 11 islands and island groups in the eastern Car- oline Islands, Micronesia. None is endemic; most occur widely in the Indo- Australian region and the islands of the western Pacific. The Lycaenidae were the most well-represented family with at least eight species. The nymphalid Hypolimnas bolina was the most frequently encountered species, occurring on all 11 island groups. Pakin Atoll, which was visited on two different occasions for a total of 5 days, was the only island group visited during this study where but- terflies were not seen. The butterfly fauna of Micronesia has contributes new locality records based largely never been comprehensively assessed. Many on recent collections and observations from of the specimens collected during the Insects eight different islands and island groups in of Micronesia Project outlined by Gressitt the eastern Caroline Islands intermittently (1954) were apparently lost after being sent between November 2001 and August 2003, on loan overseas (S. E. Miller in Buden and plus supplementary material from the Bishop Miller 2003), and no article on butterflies Museum and a small, hitherto-unreported was ever published in the Insects of Micro- collection in the College of Micronesia Land nesia series. Schreiner and Nafus (1997) Grant Office (Kolonia, Pohnpei). summarized what little is known of the ecol- ogy and distribution of species among the Study Area major islands and island groups of greater Micronesia, including the Mariana Islands, The Caroline Islands span approximately Caroline Islands, and Marshall Islands. -

Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17

Contents Part 1: Foreword Susan Denyer 3 Part 2: Context for the Thematic Study Anita Smith 5 - Purpose of the thematic study 5 - Background to the thematic study 6 - ICOMOS 2005 “Filling the Gaps - An Action Plan for the Future” 10 - Pacific Island Cultural Landscapes: making use of this study 13 Part 3: Thematic Essay: The Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific Islands Anita Smith 17 The Pacific Islands: a Geo-Cultural Region 17 - The environments and sub-regions of the Pacific 18 - Colonization of the Pacific Islands and the development of Pacific Island societies 22 - European contact, the colonial era and decolonisation 25 - The “transported landscapes” of the Pacific 28 - Principle factors contributing to the diversity of cultural Landscapes in the Pacific Islands 30 Organically Evolved Cultural Landscapes of the Pacific 31 - Pacific systems of horticulture – continuing cultural landscapes 32 - Change through time in horticultural systems - relict horticultural and agricultural cultural landscapes 37 - Arboriculture in the Pacific Islands 40 - Land tenure and settlement patterns 40 - Social systems and village structures 45 - Social, ceremonial and burial places 47 - Relict landscapes of war in the Pacific Islands 51 - Organically evolved cultural landscapes in the Pacific Islands: in conclusion 54 Cultural Landscapes of the Colonial Era 54 Associative Cultural Landscapes and Seascapes 57 - Storied landscapes and seascapes 58 - Traditional knowledge: associations with the land and sea 60 1 Part 4: Cultural Landscape Portfolio Kevin L. Jones 63 Part 5: The Way Forward Susan Denyer, Kevin L. Jones and Anita Smith 117 - Findings of the study 117 - Protection, conservation and management 119 - Recording and documentation 121 - Recommendations for future work 121 Annexes Annex I - References 123 Annex II - Illustrations 131 2 PART 1: Foreword Cultural landscapes have the capacity to be read as living records of the way societies have interacted with their environment over time. -

Polynesia and Micronesia: Sociocultural Aspects

Polynesia and Micronesia: Sociocultural Aspects Stouffer S A, Suchman E A, DeVinney L C, Star S A, Williams marangi), in Micronesia to the northwest of the R M Jr 1965 [1949] The American Soldier: Adjustments During Polynesian Triangle. Army Life. Wiley, New York, Vol. 1 Micronesia forms a wide arc of small islands Traugott M W, Lavrakas P J 2000 The Voter’s Guide to Election spanning from the western region of Insular Southeast Polls , 2nd edn. Chatham House, New York Asia to the Central Pacific, comprising the following R. Y. Shapiro island groups: Palau and outlying islands, Guam and the Mariana Islands, Caroline Islands, Marshall Islands, Gilbert Islands, and two isolated islands, Nauru and Banaba (Ocean Island). Contemporary political considerations may include island groups of the Central Pacific like the Phoenix and Line Islands; Polynesia and Micronesia: Sociocultural although geographically located in the Polynesian Aspects Triangle, these islands, which were not permanently inhabited until the modern age, are governed by The two geographical areas commonly referred to as Kiribati, the modern state based in the Gilbert Islands. ‘Polynesia’ and ‘Micronesia’ consist of a scattering of With the exception of Guam, the islands of Micronesia relatively small and widely disseminated islands across are small, although some of the largest atolls in the the central, south, and northwestern Pacific Ocean. world are found in the region (e.g., Kwajalein in the The two areas are complementary to Melanesia, the Marshalls). third area customarily -

Arts of Australia and the Pacific Islands

Arts of Australia and the Pacific Islands Jean M. Borgatti Pacific Arts include carving, weaving, painting Polynesia. Maori. NZ. Detail Australia. Arnhemland. Melanesia. Lake Sentani. Papua of an interior support figure. Basket. H. 10.5 in. Fibre, Prov. PNG Wood. Carver: Raharuhi pigment. c.1900 Roof Panel (detail). Wood, Rukupo. C.1842 pigment. H.41 in. Pre-1924. Dance and music Australia. Aboriginal dancers and musician. And such ephemera as body decoration, sand sculpture, the cultivation of yams and the giving of a gift Art=culturally significant ideas skillfully encoded in a sensuous medium Australia. Aboriginal Ground Painting. Ipolera Community. Northern Territory. Melanesia. Highland New Guinea . Body Decoration. There is a range of environments Australian Desert Marquesas Islands (Polynesia) And a range of physical types Melanesians (New Guinea) Polynesian Man (Fiji) Rock markings, Koonalda Cave Nullabor Plain, 25,000-20,000 BP Hand Stencil, Kakadu, 20-9,000 BP Dynamic figures characterize the rock art from about 10,000 BP. Fighting Scene, Rock Painting Kakadu National Park, Arnhem Land 3000-1000 Art has a deep history in this area Melanesia and Polynesia. Lapita Complex Face Design (c. 4000 BP) Melanesia. New Guinea: Ambum Stone Prehistoric period (c.8000 BP). Western Highlands Province, PNG Cultural Zone: Melanesia (The Black Islands) Cultural Zone: Micronesia (The Small Islands) Cultural Zone: Polynesia (The Many Islands) Cultural Zone: Australia (The Southern Island) Map from D’Alleva Melanesia: Ephemeral Arts Melanesia. PNG: Highlands, Mt. Hagen area. Sing-Sing. 1998 Photograph: Jean M. Borgatti Polynesia: Things that last & fine work, finish & polish Marquesas Islands. Club. Wood. 18th-19th c. -

Making a Case for Tongan As an Endangered Language

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Making a Case for Tongan as an provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Endangered Language Yuko Otsuka At fi rst glance, Tongan appears far from being endangered. It has nearly 100,000 speakers—remarkably sizable compared to other languages of Oceania—and is spoken in a predominantly monolingual and monocul- tural society.1 Furthermore, Tonga is an independent nation-state, in fact, the last kingdom in Polynesia. Why should one be talking at all about Tongan being endangered? This paper examines the linguistic situation in Tonga and argues that there are reasons to be concerned about the future of the Tongan language in the long run. The position put forward in this paper is as follows: In the postcolonial context, many instances of language endangerment should be defi ned in terms of a unit larger than a nation-state. Globalization has put small island nations like Tonga in a position such that, in order to survive, they are compelled to conform to the Western development model that is asso- ciated with English as a socioeconomically privileged language. Here, the term “globalization” refers to a particular aspect of the phenomenon, that is, interconnectedness facilitated by the expansion of Euro-American values. Interconnectedness certainly has benefi cial consequences, such as bringing new opportunities. Epeli Hau‘ofa, for example, has argued that it has empowered the peoples of Oceania, liberating them from the artifi cial boundaries imposed by nineteenth-century imperialism (1993, 10). The following discussion, however, focuses on the adverse effects of intercon- nectedness, especially as it affects language maintenance. -

The Legacy of Futuna's Tsiaina in the Languages of Polynesia"

9 The legacy of Futuna 's Tsiaina in the languages of Polynesia ROBERT LANGDON The island of Futuna, 240 km north-east of Vanualevu, Fiji, has always been virtual terra incognita to most Pacific scholars, especially English-speaking ones. Like its nearest neighbour, Wallis Island, otherwise Uvea, Futuna has been in the French sphere since French Marist missionaries established themselves there in 1837. Wallis and Futuna jointly have been both a protectorate and a colony of France. They have had the status of a French overseas territory since 1961. Most of the literature on them is naturally in French. Until fairly recently, the only way to reach them was by ship (Douglas and Douglas 1989:621-{)27). In the circumstances, not to know about the Tsiaina of Futunan tradition and not to suspect their influence on the prehistory of Polynesia and its languages has been a normal condition. Ts iaina is Futunan for 'China'. On Futuna the term describes a group of supposedly Chinese castaways who are said to have been wrecked in prehistoric times on the now uninhabited island of Alofi that is separated from Futuna by a narrow strait. The Tsiaina thereafter played a prominent role in Futunan political and cultural affairs. They were eventually overthrown in a popular uprising. There are at least six recorded versions of the Tsiaina tradition. They give the impression that the reign of the Tsiaina was quite short. In reality, the evidence presented in this paper suggests that it lasted for a goodly period-several generations, at least. Certainly, the Tsiaina left a significant legacy in the language and culture of Futuna that was also carried to other islands.