The Language of Rapa Iti: Description of a Language in Change

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Kanakanavu an Ergative Language?

Voice and transitivity in Kanakanavu Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Erfurt vorgelegt von Ilka Wild Erfurt, März 2018 Gutachter der Arbeit: Prof. Dr. Christian Lehmann, Universität Erfurt Prof. Dr. Volker Gast, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Datum der Defensio: 6. August 2018 Universitätsbibliothek Erfurt Electronic Text Center URN:nbn:de:gbv:547-201800530 Abstract This is a dissertation on the Kanakanavu language, i.e. that linguistic phenomena found while working on the language underwent a deeper analysis and linguistic techniques were used to provide data and to present analyses in a structured manner. Various topics of the Kanakanavu language system are exemplified: Starting with a grammar sketch of the language, the domains phonology, morphology, and syntax are described and information on the linguistic features in these domains are given. Beyond a general overview of the situation and a brief description of the language and its speakers, an investigation on a central part of the Kanakanavu language system, namely its voice system, can be found in this work. First, it is analyzed and described by its formal characteristics. Second, the question of the motivation of using the voice system in connection to transitivity and, in the literature less often recognized, the semantic side of transitive constructions, i.e. its effectiveness, is discussed. Investigations on verb classes in Kanakanavu and possible semantic connections are presented as well as investigations on possible situations of different degrees of effectiveness. This enables a more detailed view on the language system and, in particular, its voice system. -

Prayer Cards (709)

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations A Che in China A'ou in China Population: 43,000 Population: 2,800 World Popl: 43,000 World Popl: 2,800 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Tibeto-Burman, other People Cluster: Tai Main Language: Ache Main Language: Chinese, Mandarin Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net Source: Operation China, Asia Harvest www.joshuaproject.net Source: Operation China, Asia Harvest "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations A-Hmao in China Achang in China Population: 458,000 Population: 35,000 World Popl: 458,000 World Popl: 74,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Miao / Hmong People Cluster: Tibeto-Burman, other Main Language: Miao, Large Flowery Main Language: Achang Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Significantly reached Status: Partially reached Evangelicals: 75.0% Evangelicals: 7.0% Chr Adherents: 80.0% Chr Adherents: 7.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Wikipedia "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Achang, Husa in China Adi -

Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific)

quaternary Review Human Discovery and Settlement of the Remote Easter Island (SE Pacific) Valentí Rull Laboratory of Paleoecology, Institute of Earth Sciences Jaume Almera (ICTJA-CSIC), C. Solé i Sabarís s/n, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] Received: 19 March 2019; Accepted: 27 March 2019; Published: 2 April 2019 Abstract: The discovery and settlement of the tiny and remote Easter Island (Rapa Nui) has been a classical controversy for decades. Present-day aboriginal people and their culture are undoubtedly of Polynesian origin, but it has been debated whether Native Americans discovered the island before the Polynesian settlement. Until recently, the paradigm was that Easter Island was discovered and settled just once by Polynesians in their millennial-scale eastward migration across the Pacific. However, the evidence for cultivation and consumption of an American plant—the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas)—on the island before the European contact (1722 CE), even prior to the Europe-America contact (1492 CE), revived controversy. This paper reviews the classical archaeological, ethnological and paleoecological literature on the subject and summarizes the information into four main hypotheses to explain the sweet potato enigma: the long-distance dispersal hypothesis, the back-and-forth hypothesis, the Heyerdahl hypothesis, and the newcomers hypothesis. These hypotheses are evaluated in light of the more recent evidence (last decade), including molecular DNA phylogeny and phylogeography of humans and associated plants and animals, physical anthropology (craniometry and dietary analysis), and new paleoecological findings. It is concluded that, with the available evidence, none of the former hypotheses may be rejected and, therefore, all possibilities remain open. -

A Brief Ethnohistory of Rapa Island, French Polynesia, AD 1791–1840

2 ‘Dwelling carelessly, quiet and secure’ A brief ethnohistory of Rapa Island, French Polynesia, AD 1791–1840 Atholl Anderson Department of Archaeology and Natural History, Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, [email protected] Introduction In 1826, the first European missionary to Rapa, the Rev. John Davies, quoted Judges 18:7 in seeing the Rapans as ‘dwelling carelessly, quiet and secure, and having no business with any man’ (in Stokes n.d.:28; an idiomatic rendering of the passage). It was to some extent, possibly to a great extent, quite illusory. Rapa was certainly isolated by comparison with most of East Polynesia, and it was small, mountainous and relatively cold, but even the first European visitors found that Rapans exhibited evidence of contact with the outside world, and within Rapan traditions, historical observations and ethnographic data which together form the stuff of ethnohistory, the theme of contact and change is illustrated continually. Rapan society was East Polynesian in ancestry and culture. Rapans spoke an East Polynesian language, but its closest affinities were puzzling for a long time. The earliest historical contacts with Rapans showed that they found both Hawaiian and Tahitian largely unintelligible and later characterisation of Rapan by European scholars was confused because of the early introduction of Tahitian by missionaries and, after 1863, of other Polynesian languages by Tongans, Tokelauans and Cook Islanders, whose descendants came eventually to represent nearly half of the population (Stokes 1955). Samuel Stutchbury had observed, presciently, in 1826 (in Richards 2004:5) that the Rapan language was ‘something resembling the Marquesan’, but Horatio Hale (1968:141), about 1840, ‘obtained at Tahiti, from a native of Rapa, a brief vocabulary of the language spoken there, which turns out to be, with a few verbal exceptions, pure Rarotongan, and this in its minute peculiarities’, while the missionaries William Ellis (1838) and M. -

Report for the 2002 Pacific Biological Survey, Bishop Museum Austral Islands, French Polynesia Expedition to Raivavae and Rapa Iti

Rapa K.R. Wood photo New Raivavae Damselfly Sicyopterus lagocephalus: Raivavae REPORT FOR THE 2002 PACIFIC BIOLOGICAL SURVEY, BISHOP MUSEUM AUSTRAL ISLANDS, FRENCH POLYNESIA EXPEDITION TO RAIVAVAE AND RAPA ITI Prepared for: Délégation à la Recherche (Ministère de la Culture, de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche), B.P. 20981 Papeete, Tahiti, Polynésie française. Prepared by: R.A. Englund Pacific Biological Survey Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817 March 2003 Contribution No. 2003-004 to the Pacific Biological Survey 2002 Trip Report: Expedition to Raivavae and Rapa, Austral Islands, French Polynesia TABLE OF CONTENTS Résumé ..................................................................................................................................................................iii Abstract.................................................................................................................................................................. iv Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 Study Area.............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Aquatic Habitats- Raivavae .............................................................................................................................. 3 Aquatic Habitats- Rapa.................................................................................................................................... -

SOUTHERN LISU DICTIONARY Qaaaqrc Qbq[D @^J Hell Ebll Ell

STEDT Monograph Series, No. 4 James A. Matisoff, general editor SOUTHERN LISU DICTIONARY QaaaqRc Qbq[d @^j Hell Ebll ell David Bradley with Edward Reginald Hope, James Fish and Maya Bradley Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus Project Center for Southeast Asia Studies University of California, Berkeley 2006 © 2005 David Bradley All Rights Reserved ISBN 0-944613-43-8 Volume #4 in the STEDT Monograph Series Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus Project <http://stedt.berkeley.edu/> Department of Linguistics research unit in International and Area Studies University of California, Berkeley Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus Monograph Series General Editor JAMES A. MATISOFF University of California, Berkeley Previous Titles in the STEDT Monograph Series: STEDT MONOGRAPH NO. 1A: Bibliography of the International Conferences on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics I-XXV (second edition) STEDT MONOGRAPH NO. 2: Annotated Directory of Tibeto-Burman Languages and Dialects (revised) STEDT MONOGRAPH NO. 3: Phonological Inventories of Tibeto- Burman Languages Author’s Dedication: for my Lisu friends CONTENTS Series Editor’s Introduction vii Introduction xv The Lisu xv Lisu Phonology xviii Lisu Orthographies xxv Lisu Syntax xxviii Acknowledgements xxix References xxxi Hel Bck Ubl (Lisu Introduction) xxxiii List of Abbreviations xxxiv @ b 1 @\ bj 14 A p 17 A\ pj 31 B pæ 33 B\ pæj 42 C d 45 D t 56 E tæ 70 F g 80 G k 87 H kæ 101 I dÔ 112 J tΔ 121 K tΔæ 133 L dz 146 M ts 155 N tsæ 163 O m 173 O\ mj 194 P n 198 -

LING 185 the Syntax of Austronesian Languages Preliminary Syllabus

LING 185 The Syntax of Austronesian Languages Preliminary syllabus The goal of this class is to provide an introduction into comparative Austronesian syntax by discussing the most pertinent issues of Austronesian languages that have posed challenge to current syntactic theory and suggesting further readings and topics for discussion. The choice of the Austronesian language family as the focus of this class is not accidental. The Austronesian language family—roughly 1,200 genetically related languages dispersed over an area encompassing Madagascar, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and islands of the Pacific—is often called the largest language family in the world. But it has been relatively little studied. Sophisticated research on the grammar of Austronesian languages did not really begin until the 1930’s and 1940’s (fueled, in part, by military interest in the Pacific region). Although there was a surge of interest in Austronesian in the 1970’s and—even more dramatically—in the 1990’s, the number of theoretical linguists working on these languages has remained small. Nonetheless, Austronesian languages have a significant contribution to make to linguistic theory, given the number of typologically unusual properties they exhibit (including the less common and poorly understood verb‐first word order, ergativity, and wh‐ agreement). If these languages were as well‐understood as, say, the Romance languages are today, syntactic theory could well be dramatically different. The following list illustrates just some of the intriguing features whose theoretical significance—already evident—will surely deepen when they are investigated from a comparative perspective: • Many Austronesian languages exhibit the uncommon word orders verb‐subject‐object (VSO) or verb‐object‐subject (VOS). -

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

Tuamotuan Phonology

SERIES B - No. 17 TUAMOTUAN PHONOLOGY by Hiroshi Kuki PACIFIC LINGUISTICS The Australian National University Kuki, H. Tuamotuan phonology. B-17, x + 130 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1970. DOI:10.15144/PL-B17.cover ©1970 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PAC IFIC LINGUISTICS is published by the L�ngu�4t�c C��cte 06 Canbe��a and consists of four series : SERIES A - OCCASI ONAL PA PERS SERIES B - MONOGRAPHS SERIES C - BOOKS SERIES V - SPECIAL PUBLICATIONS . EDITOR: S.A. Wurm . ASSOCIATE EDITORS: D.C. Laycock, C.L. Voorhoeve . EDITORIAL CORRESPONDENCE: The Editor, PAC IFIC LINGUISTICS, Department of Linguistics, School of Pacific Studies, The Au stralian National University, Box 4, P.O., Canberra , A.C.T. 2600 . Australia . SUBSCRIPTIONS AND SALES: ABOVE ADDRESS Copyright (§) Hiroshi Kuki . First published 1970. The editors are indebted to the Australian National University for help in the product ion of this series . This publicat ion was made possible by an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund . PR EFACE This study is based upon a corpus of recorded tapes and a subsequent analysis of them during linguistic fieldwork in Papeete, Tahiti, French Polynesia in June-August 1967 with the supervision of Dr. Bruce Biggs under the Polynesian Pre-History Program of the Bernice P. Bishop Muse um, Honolulu, Hawaii, and also on further study in Laie and Honolulu, Oahu, H�waii, in 1967-68. It was my original intention to use ten to twenty pages for phonology and devote the rest of the work to discussions of Tuamotuan morphology syntax. -

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

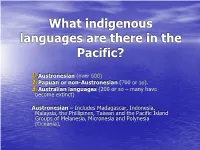

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

Pacific Islands

THE PACIFIC ISLANDS POLITICS, ECONOMICS, AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS TE'O I.J. FAIRBAIRN CHARLES E. MORRISON RICHARD W. BAKER SHEREE A. GROVES THE PACIFIC ISLANDS THE EAST-WEST CENTER was established in Hawaii in 1960 by the United States Congress "to promote better relations and understand ing between the United States and the nations of Asia and the Pacific through cooperative study, training, and research:' Some 2,000 research fellows, graduate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's interna tional staff on major Asia-Pacific issues relating to population, economic and trade policies, resources and the environment, culture and com munication, and international relations. Since 1960, more than 27,000 men and women from the region have participated in the Center's cooperative programs. Officially known as the Center for Cultural and Technical Inter change Between East and West, Inc., the Center is a public, non-profit institution with an international board of governors. Principal funding comes from the United States Congress. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agen cies and corporations. THE INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS PROGRAM (JRP) became an autonomous program within the East-West Center in 1989. The Program advances the Center's overall objectives through work on foreign poli cy and related political, economic, and security issues. Program pri orities are to 1) promote research and dialogue directed toward creating a stable, peaceful Asia/Pacific community; 2) identify issues in U.S. re lations with the Asia/Pacific region and recommend means of strength ening these relations; 3) improve understanding of individual societies of the region through cooperative research; and 4) promote contact and dialogue among the region's future leaders. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general