Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori O Te Pae Tonga O Te Kuki Airani Also Known As Southern Cook Islands Māori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Va‟O Mai I Te Akao: Beyond the Reef

Va‟o mai i te Akao: Beyond the reef Transnational health promotion among Cook Islands people Rochelle Newport Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Health Science (Honours) University of Auckland 2011 I Abstract Introduction Transnationalism describes the social spaces and ties migrant communities maintain with their country of origin. These spaces are used for multiple purposes including health promotion, and social support. Cook Islanders have a long history of migration to New Zealand and there is evidence which suggest strong social networks and ties exist between Cook Islanders in New Zealand and the Cook Islands. The transnational ties Cook Islanders maintain are potential sites for health promotion activities. This research has investigated transnational health promotion activities with Cook Islanders using health promotion activities to reduce the prevalence of obesity as a lens. Methods Participant observations and interviews were conducted in Rarotonga, Cook Islands and Auckland, New Zealand. Observations were recorded in field notes and a thematic analysis was conducted. Findings Health promotion in the Cook Islands takes a multi-level approach consistent with a socio-ecological approach to health promotion. Food, culture and physical activity are interrelated among Cook Islanders and the cultural implications of health promotional activities should be accounted for during programme development. Cook Islanders maintain reciprocal social networks and share resources for health gain. Among the interviewees a desire and need for collaboration to share skills and resources for health promotion was expressed. Conclusion There is potential for health promotion activities in the Cook Islands to operate transnationally utilising transnational social spaces as a site for community capacity building. -

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

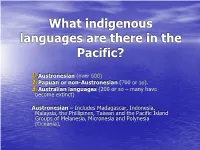

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

Co-Operation Among Cook Islanders Living in New Zealand

CO-OPERATION AMONG COOK ISLANDERS LIVING IN NEW ZEALAND Research into the impact of the Cook Islands Development Agency of New Zealand’s oneCO-OPERATIVE Model Prepared by Valerie Proud of Co-Creationz March 2018 CONTENTS Executive Summary............................................................................................................ 1 Background......................................................................................................................... 3 Who is CIDANZ?....................................................................................................... 3 Terms ................................................................................................................................... 5 The Global Context ............................................................................................................ 6 A Cook Islands Development Agency In New Zealand.................................................. 8 Ta’okota’i................................................................................................................... 8 Community Development & The Five Capitals.................................................... 9 The Place.................................................................................................................. 11 The Programmes..................................................................................................... 11 Building On Firm Foundations - The Turanga Project............................. 11 From Turanga To Ora’anga Mou............................................................... -

The Cook Islands and the Pacific Island Nations: Will the Last Person Leaving Please Turn Off the Lights?

Volume 6 | Issue 11 | Article ID 2951 | Nov 01, 2008 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Cook Islands and the Pacific Island Nations: Will the Last Person Leaving Please Turn Off the Lights? Andre Vltchek The Cook Islands and the Pacific Island main island of the country, but its coastal road Nations: Will the Last Person Leaving runs only a bit over 31km. Please Turn Off the Lights? Andre Vltchek From Rarotonga, the Cook Islands. The sea is blue, beaches with golden sand boast palm trees bending almost to the water surface. Beneath barely detectable waves, marine life is fascinating and diverse. On hotel terraces, coconut juices cool the refined throats of jet setters. Traditional huts rub shoulders with some of the most expensive resorts in the world. 500 US dollars would hardly sustain a couple for more than a day here in one of the Muri Beach, Rarotonga most expensive parts of the world. Together with neighboring French Polynesia, this has The Cook Islands, a former New Zealand become one of the most expensive parts of the colony, is a subdued English-speaking answer world. to its Francophone neighbor, one of the most lavishly posh places on earth, French Polynesia with its hedonistic icon Bora-Bora. Rarotonga Welcome to Rarotonga – the main island of “Cooks”, a country spanning a huge expanse of the Western Pacific, but with a combined land mass of just 236.7 sq kms. “Raro” may be the Cook Islands map 1 6 | 11 | 0 APJ | JF With all that beauty, one would expect an people are leaving”, enormous influx of foreigners searching for sun explained painter Ani and sea, and a local demographic explosion to Exham-Dun, who owns serve them. -

The Phonemic Reality of Polynesian Vowel Length

The Phonetic Nature of Niuean * Vowel Length Nicholas Rolle University of Toronto In this paper, I argue that in Niuean, long vowels are underlying sequences of two qualitatively identical vowels, extending an analysis laid out in Taumoefolau (2002) on the related Tongic language Tongan. She argues that a long vowel will result predictably when stress falls on the first element of a double monophthong vowel sequence. Thus vowel length in these languages is a phonetic, not phonological, phenomenon. This account for vowel length is worked into an Optimality Theory (OT) framework, which crucially constrains RH- CONTOUR and ALL-FT-RIGHT above a constraint against double articulation, DIST(INCT). In addition, I provide a review of the literature concerning vowel length across Polynesian languages, and conclude that this analysis cannot be extended to all members of the Polynesian language family. 1. Introduction Across Polynesian languages, the presence of long vowels is uncontroversial, though whether these are only surface long vowels (i.e. phonetic) or underlying long vowels (i.e. phonemic) remains a contentious topic. In this paper, I outline an analysis of Tongan long vowels laid out in Taumoefolau (2002), and later supported by Anderson & Otsuka (2006), and extend this analysis to the related Tongic language Niuean. It is argued in Taumoefolau (2002) that Tongan long vowels are underlying identical vowel-vowel sequences (/ViVi/), whose surface manifestation is predictably a long vowel if stress falls on the first vowel of this sequence, and a double articulated vowel if stress falls on the second. This analysis is laid out in detail in section 3, preceded by a section describing some basic facts of Tongan phonology, and a review of the previous analyses of Tongan vowel length. -

Telling Pacific Lives

TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS TELLING PACIFIC LIVES PRISMS OF PROCESS Brij V. Lal & Vicki Luker Editors Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/tpl_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Telling Pacific lives : prisms of process / editors, Vicki Luker ; Brij V. Lal. ISBN: 9781921313813 (pbk.) 9781921313820 (pdf) Notes: Includes index. Subjects: Islands of the Pacific--Biography. Islands of the Pacific--Anecdotes. Islands of the Pacific--Civilization. Islands of the Pacific--Social life and customs. Other Authors/Contributors: Luker, Vicki. Lal, Brij. Dewey Number: 990.0099 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Cover image: Choris, Louis, 1795-1828. Iles Radak [picture] [Paris : s.n., [1827] 1 print : lithograph, hand col.; 20.5 x 26 cm. nla.pic-an10412525 National Library of Australia Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2008 ANU E Press Table of Contents Preface vii 1. Telling Pacic Lives: From Archetype to Icon, Niel Gunson 1 2. The Kila Wari Stories: Framing a Life and Preserving a Cosmology, Deborah Van Heekeren 15 3. From ‘My Story’ to ‘The Story of Myself’—Colonial Transformations of Personal Narratives among the Motu-Koita of Papua New Guinea, Michael Goddard 35 4. Mobility, Modernisation and Agency: The Life Story of John Kikang from Papua New Guinea, Wolfgang Kempf 51 5. -

PACIFIC ISLANDS (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga)

PACIFIC ISLANDS (Fiji, Samoa, Tonga) Who is a Pacific Islander? The “Pacific Islands” is how we are described because of our geographic location, “Islands, geographically located in the Pacific Ocean”. Today, we will talk and share with educators, health experts, and community members of the three dominant Pacific Islander populations who live in San Mateo County, namely, Fijians, Samoans, and Tongans. PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS • When you talk about the Pacific Islands, you are talking about different Island Nations. • Different heads of countries, from kings to presidents, etc. Even different forms of government. • Some are independent countries, yet some are under the rule of a foreign power. PACIFIC ISLAND NATIONS • Each Island Nation has their own language. • There is not one language that is used or understood by all Pacific Islanders. • There are some similarities but each island nation has it’s own unique characteristics. • Challenge in grouping the islands as just one group, “Pacific Islanders”. ISLANDS OF THE PACIFIC GREETINGS • From the Islands of Fiji “Bula Vinaka” • From the Islands of Samoa “Talofa Lava” • From the Kingdom of Tonga “Malo e Lelei” • From Chamorro “Hafa Adai” • From Tahiti “Ia Orana” • From Niue “Fakalofa atu” • From NZ Maoris “Tena Koe” • From Hawaii “Aloha” FIJI ISLANDS • Group of volcanic islands in the South Pacific, southwest of Honolulu. • Total of 322 islands, just over 100 are inhabited. • Biggest island Viti Levu, is the size of the “Big Island” of Hawaii. • Larger islands contain mountains as high as 4,000 feet. PEOPLE OF FIJI • Indigenous people are Fijians who are a mixture of Polynesian and Melanesian. -

RAROTONGA, AITUTAKI, ATIU and SISTER ISLANDS London

visit us at: COOK ISLANDS GUIDE COOKISLANDS.TRAVEL RAROTONGA, AITUTAKI, ATIU AND SISTER ISLANDS London Berlin Vancouver Rome Beijing Seoul To kyo Los Angeles Hong Kong Honolulu Tahiti Perth Capetown Sydney Auckland Kia Orana iscover our hidden gem of the South Pacific and you’ll see why there’s so much more to a little paradise. Unspoilt, simple and so easy to get around, you can explore and play as much or as little as you want in this oasis of absolute freedom. Let the untouched charm of these beautiful islands and friendly locals capture your spirit and envelope your heart. The 15 islands of the Cooks lie halfway between New Zealand and Hawaii, scattered like fragrant flower petals floating across 2.2 million square kilometres of a serene, opulent ocean. Boasting rare beauty, an idyllic climate, warm welcoming people with heart felt smiles and a pace of life unsurpassed. We invite you to endless adventure, romance and pure relaxation. Come explore and share the Cook Islands with us, and discover why everyone loves a little paradise. For more information regarding flight schedules to the Cook Islands please refer to: www.cookislands.travel/flightinformation cookislands.travel | 3 CONTENTS Welcome 2 How to get here 4 HOW TO Rarotonga – our capital 6 purchase duty-free goods. Be prepared to Aitutaki – heaven on earth 24 GET HERE receive a traditional ei, a garland of fragrant flowers as you leave the airport. The best part Atiu – the island of birds 36 is yet to come, a trip from the airport to your Mauke – the garden island 42 Although we’re a little paradise, we’re accommodation right on the beach is less serviced by big players: Air New Zealand than 30 minutes, anywhere on the island. -

Fact Sheet for Entry to the Cook Islands in Response to COVID-19 Travel Restrictions from 20 June 2020

Government of the Cook Islands Te Kauono Tutara e te Mana Tiaki - Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Immigration Fact Sheet for entry to the Cook Islands in response to COVID-19 travel restrictions from 20 June 2020 In response to the Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, the Cook Islands has established COVID-19 as a notifiable and dangerous condition under Schedule 2 of the Public Health Act (2004) and the COVID-19 Act (2020). As such, the following travel restriction is currently in force: REOPENING OF BORDERS On the 2nd June 2020, the Prime Minister Hon. Henry Puna, approved the opening of the Cook Islands borders for entry from the 19th June 2020. This is restricted to Cook Islanders and Permit Holders provided that the person travelling has not been outside of New Zealand/Cook Islands in the 30 days prior to travel. Visitor permits are not being issued at this time. For further enquires please contact: [email protected] STANDARD ENTRY REQUIREMENTS Persons who identify as Cook Islanders maybe required to provide evidence; eg Cook Islands Status stamp. All permit holders, must have a valid permit at time of travel. [email protected] for any enquiries. FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS “What if I don’t have my Cook Islands Status stamp in my passport?” If your birth place on your passport is in the Cook Islands, you do not require a Cook Islands Status stamp at this time. If your birth place is outside of the Cook Islands, we may need more information, please email: [email protected] and we will assist you. -

Making a Case for Tongan As an Endangered Language

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Making a Case for Tongan as an provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Endangered Language Yuko Otsuka At fi rst glance, Tongan appears far from being endangered. It has nearly 100,000 speakers—remarkably sizable compared to other languages of Oceania—and is spoken in a predominantly monolingual and monocul- tural society.1 Furthermore, Tonga is an independent nation-state, in fact, the last kingdom in Polynesia. Why should one be talking at all about Tongan being endangered? This paper examines the linguistic situation in Tonga and argues that there are reasons to be concerned about the future of the Tongan language in the long run. The position put forward in this paper is as follows: In the postcolonial context, many instances of language endangerment should be defi ned in terms of a unit larger than a nation-state. Globalization has put small island nations like Tonga in a position such that, in order to survive, they are compelled to conform to the Western development model that is asso- ciated with English as a socioeconomically privileged language. Here, the term “globalization” refers to a particular aspect of the phenomenon, that is, interconnectedness facilitated by the expansion of Euro-American values. Interconnectedness certainly has benefi cial consequences, such as bringing new opportunities. Epeli Hau‘ofa, for example, has argued that it has empowered the peoples of Oceania, liberating them from the artifi cial boundaries imposed by nineteenth-century imperialism (1993, 10). The following discussion, however, focuses on the adverse effects of intercon- nectedness, especially as it affects language maintenance. -

Kaikava Me Kare Inuinu Kaikava Me Kare Inuinu

Kaikava me kare Inuinu Kaikava me kare Inuinu The place of alcohol in the lives of Cook Islands people living in Aotearoa New Zealand A report prepared by Sector Analysis, Ministry of Health for the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand ALAC Research Monograph Series: No 7 Wellington 1997 ISSN 1174-1856 ISBN 0-477-06322-5 Explanation of Title Kaikava me kare inuinu: Kaikava is to drink alcohol; inuinu is the process of drinking (sipping). The title implies that people drink for different purposes and their drinking reflects the level of social interaction. Acknowledgements We would like to thank all those people who took part in the interviews and shared their stories with us. This report has only been possible because of their willingness to take part. Our thanks to Jean Mitaera and Repeta Puna-Turia who read the report and made helpful comments. Kia orana Anne Allan-Moetaua, Lanuola Asiasiga, Ian Hodges, Helen Kapi and Terongo Tekii Cook Islands Border Design Vaitoa Baker As a freelance illustrator of mixed ethnic groups, having the opportunity to work on this project that incorporates many designs of the Pacific, I hope I have done justice to each. I also want to give thanks to my partner, Yvette, whose love keeps me going. Disclaimer This report was prepared by staff of Sector Analysis, Ministry of Health for the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand. Its purpose is to inform discussion and assist future health promotion strategies. Therefore, the opinions expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Alcohol Advisory Council of New Zealand, Ministry of Health nor the members of the field team.