Making a Case for Tongan As an Endangered Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portrayals of the Moriori People

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. i Portrayals of the Moriori People Historical, Ethnographical, Anthropological and Popular sources, c. 1791- 1989 By Read Wheeler A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History, Massey University, 2016 ii Abstract Michael King’s 1989 book, Moriori: A People Rediscovered, still stands as the definitive work on the Moriori, the Native people of the Chatham Islands. King wrote, ‘Nobody in New Zealand – and few elsewhere in the world- has been subjected to group slander as intense and as damaging as that heaped upon the Moriori.’ Since its publication, historians have denigrated earlier works dealing with the Moriori, arguing that the way in which they portrayed Moriori was almost entirely unfavourable. This thesis tests this conclusion. It explores the perspectives of European visitors to the Chatham Islands from 1791 to 1989, when King published Moriori. It does this through an examination of newspapers, Native Land Court minutes, and the writings of missionaries, settlers, and ethnographers. The thesis asks whether or not historians have been selective in their approach to the sources, or if, perhaps, they have ignored the intricacies that may have informed the views of early observers. The thesis argues that during the nineteenth century both Maori and European perspectives influenced the way in which Moriori were portrayed in European narrative. -

And Taewa Māori (Solanum Tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Traditional Knowledge Systems and Crops: Case Studies on the Introduction of Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and Taewa Māori (Solanum tuberosum) to Aotearoa/New Zealand A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Master of AgriScience in Horticultural Science at Massey University, Manawatū, New Zealand Rodrigo Estrada de la Cerda 2015 Kūmara and Taewa Māori, Ōhakea, New Zealand i Abstract Kūmara (Ipomoea batatas) and taewa Māori, or Māori potato (Solanum tuberosum), are arguably the most important Māori traditional crops. Over many centuries, Māori have developed a very intimate relationship to kūmara, and later with taewa, in order to ensure the survival of their people. There are extensive examples of traditional knowledge aligned to kūmara and taewa that strengthen the relationship to the people and acknowledge that relationship as central to the human and crop dispersal from different locations, eventually to Aotearoa / New Zealand. This project looked at the diverse knowledge systems that exist relative to the relationship of Māori to these two food crops; kūmara and taewa. A mixed methodology was applied and information gained from diverse sources including scientific publications, literature in Spanish and English, and Andean, Pacific and Māori traditional knowledge. The evidence on the introduction of kūmara to Aotearoa/New Zealand by Māori is indisputable. Mātauranga Māori confirms the association of kūmara as important cargo for the tribes involved, even detailing the purpose for some of the voyages. -

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

Maori & Pasifika Infants and Toddlers

Tangata Pasifika: Sustaining cultural knowledge and language competency for Pacific peoples. Presentation at the Victoria University Autumn Research Seminar, May 2018. Ali Glasgow Faculty of Education Language, culture, identity • A leai se gagana, ona leai lea o sa ta aganu’u, a leai la ta aganu’u ona po lea o le nu’u (Samoan proverb) • If there is no language, then there is no culture, • If there is no culture, then all of the village will be in darkness Presentation outline • My background • Pacific context • Aoteroa New Zealand context – culture, language • Research findings – Vuw Summer Scholarship (2015), TLRI ( Teaching and Learning Research Initiative, 2017). Ali – Kuki Airani – Tongareva Atoll Pacific perspectives • Pacific region located historically, contextually and geographically within Oceania, more particularly in the region of the Southern Pacific referred to as the Polynesian triangle (Ritchie & Ritchie, 1970) • ‘Our sea of islands ( Hau’ofa, 1993) Reclaiming & Reconceptualising Pacific Education • Pacific Education (currently) prioritises the voice and worldview of the outside which amputates our capacity for human agency. Within the Pacific the bulk of what we teach and learn in our schools and at our universities and colleges in the Pacific is what has been conceptualised and developed in and for the Western world (Koya-Vakauta,2016). • The indigenous peoples of the Pacific need to create their own pedagogy... rooted in Pacific values, assumptions, processes and practices ( Glasgow, 2010; Mara, Foliaki & Coxon, 1994; Tangatapoto,1984 & Taufe’ulungake, 2001). Aspiration Statement ( MOE, 2017, p.5) • Competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society. -

Laulōtaha; Tongan Perspectives of 'Quality' in Early Childhood Education Dorothy Lorraine Pau'uvale a Thesis Submitted To

Laulōtaha; Tongan Perspectives of ‘Quality’ in Early Childhood Education Dorothy Lorraine Pau’uvale A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Master of Education (MEd) 2011 School of Education i Table of Contents List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... vi Attestation of Authorship .................................................................................................. vii Fakamālō/ Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ viii Ethical Approval .............................................................................................................. xiii Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: Talateu/ Introduction ......................................................................................... 2 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Purpose of the study .................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Context of the study .................................................................................................. 3 1.4 Importance of the study ........................................................................................... -

Palauea, Honua'ula, Maui

OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS RESEARCH DIVISION Palauea Palauea, Honua‘ula, Maui By Holly K. Coleman Palauea is the name of an ahupua‘a (land division) in the moku (district) of Honua‘ula on the island of Maui. Many believe that Palauea and surrounding areas were focal points and ceremonial centers of the fishing communities of Honua‘ula (Six, 2013). Today, a high concentration of archaeological and cultural sites can be found in the Pa- lauea Cultural Preserve, which is one of the few undevel- oped land parcels in an area surrounded by luxury resi- dences and resorts. At least fourteen native plant species, including what is believed to be the largest natural stand of maiapilo (Capparis sandwichiana), and at least thirteen archaeological complexes have been identified within the preserve area (Donham, 2007). In April 2013, the Dowling Corporation formally con- veyed the Palauea Cultural Preserve to the Office of Ha- waiian Affairs (OHA). Palauea remains a vital cultural and historical resource for Native Hawaiians and the broader community. The goal of this Information Sheet is to explore some of the cultural and historical narratives of Palauea and the surrounding areas, particularly as OHA transitions into the role of care- taker of this place. This Information Sheet will also strengthen the agency’s foundation of knowledge for this wahi pana (storied, legendary place). Left: View of Molokini and Kaho‘olawe from Palauea Heiau. Source: Shane Tegarden Photography for OHA, 2013. Research Division Land, Culture, and History Section Information Sheet, October 2013 Office of Hawaiian Affairs 560 N. Nimitz Hwy, Suite 200, Honolulu, HI 96817 www.oha.org 1 OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS RESEARCH DIVISION Traditional Land Divisions Winds and Rains of Honua‘ula Honua‘ula was known as a dry land; indeed, Honua‘ula means “red land or earth” and may have also been the named for a variety of sweet potato grown in the area as a staple food (Pukui & Elbert, 1974). -

Celebration of the Niuean Language and Culture Ko E Tau Fakafiafiaaga

Celebration of the #pacificstars Niuean Language and Culture Ko e tau Fakafiafiaaga he Vagahau Niue mo e tau Aga Fakamotu Facts on Niue | Folafolaaga hagaaoia Population | Puke tagata ke he motu ko Niue In 2013 Niue peoples were the fourth largest Pacific • Niue is one of the world's largest coral islands. ethnic group in New Zealand making up 8.1% or 23,883 • Niue (pronounced “New-e (‘e’ as in ‘end’ – which means of New Zealand’s Pacific peoples’ population. 'behold the coconut') may be the world’s smallest The most common region this group lived in was the independent nation. Auckland Region (77.7 percent or 18,555 people), followed • The island is commonly referred to as "The Rock", by the Wellington Region (6.6 percent or 1,575 people), a reference to Niue being one of the biggest raised and the Waikato Region (4.3 percent or 1,038 people). coral islands in the world. The median age was 20.4 years. • The capital of Niuē is the village of Alofi. • Niueans are citizens of New Zealand. 78.9 percent (18,465 people) were born in New Zealand. • Niue is an elevated coral atoll with fringing coral reefs encircling steep limestone cliffs. It has a landmass of 259km and its highest point is about 60 metres In 2013 Niue peoples made up above sea level. • Niue lies 2400 km northeast of New Zealand 23,883 between Tonga, Samoa and the Cook Islands. of New Zealand's Pacific peoples' population History | Tau Tala Tu Fakaholo Polynesians from Samoa settled Niue around 900 AD. -

Gender & Interaction in a Globalizing World: Negotiating the Gendered

Chapter 13 Gender and interaction in a globalizing world: Negotiating the gendered self in Tonga* Niko Besnier 1. Gender and language in microscopic and macroscopic perspectives One of the more important developments in our understanding of the rela- tionship between language and gender in the last couple of decades is the recognition that the gendering of language is semiotically complex. Indeed, linguistic forms and practices do not define “women’s language” and “men’s language”, as earlier researchers argued (e.g., Lakoff 1975), but articulate with a host of social categories and processes that surround gen- der and help construct it. The clearest articulation of this position is Ochs’ (1992) demonstration that gendered linguistic practices are both indexical and indirect. Indexicality captures the insight that features of language (phonological, syntactic, discursive, etc.) “point to”, or suggest, gendered identities, and do not refer to gender in an unequivocal fashion, as linguistic symbols would. In this respect, the relationship between language and gen- der is no different from the relationship between language and any other aspect of socio-cultural identity, as we have known since the early days of sociolinguistics (Labov 1966a). However, the indexical linking of language and gender presents another layer of complexity: linguistic resources are semiotically connected to gender through the mediation of other aspects of the socio-cultural world. For example, features of language and interaction invoke social roles (e.g., mother, CEO, construction work), demeanors (e.g., politeness, authority, or the lack thereof), and activities (e.g., forms of work and play), all of which are in turn indexically associated with gender (see Figure 1). -

Hawaiian Language Normalization: an Analysis of L2 Hawaiian Speaker Narratives

HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE NORMALIZATION: AN ANALYSIS OF L2 HAWAIIAN SPEAKER NARRATIVES KAPUAOKEKOʻOLAUIKAULUPUA ANGELINE LEIKO ADAMS University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa ABSTRACT This study analyzes the degree to which the Hawaiian language has become normalized in a range of domains beyond language learning contexts for L2 Hawaiian speakers. First, two in- depth interviews were conducted with two graduate students in the Hawaiʻinuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa (UHM). The interviews were then analyzed using narrative analysis and were organized thematically according to where students report that they use Hawaiian language in and outside of the UHM campus. The narrative data were then used to create a questionnaire to survey 32 students who are self- identified proficient speakers of Hawaiian at UHM about where they use Hawaiian and for what purpose they use Hawaiian in different places and spaces in their lives. The data provide more insight into language normalization by showing where L2 Hawaiian speakers are using Hawaiian in their lives. The findings also provide valuable implications for the ongoing revitalization of ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi and give a clearer picture of L2 language use. INTRODUCTION “E ola mau ka ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi” is a Hawaiian proverb or ʻōlelo noʻeau that translates to “the Hawaiian language lives on” (Pukui, 1983). This ʻōlelo noʻeau has been a sort of slogan for the revitalization efforts of the Hawaiian language. It is one of the most popular sayings among second language learners and speakers about their mission to kōkua or help the Hawaiian language grow stronger. Learning the Hawaiian language is challenging since there are not many native speakers of the language. -

Rekohu Report (2016 Newc).Vp

Rekohu REKOHU AReporton MorioriandNgatiMutungaClaims in the Chatham Islands Wa i 6 4 WaitangiTribunalReport2001 The cover design by Cliff Whiting invokes the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the consequent interwoven development of Maori and Pakeha history in New Zealand as it continuously unfoldsinapatternnotyetcompletelyknown AWaitangiTribunalreport isbn 978-1-86956-260-1 © Waitangi Tribunal 2001 Reprinted with corrections 2016 www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz Produced by the Waitangi Tribunal Published by Legislation Direct, Wellington, New Zealand Printed by Printlink, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Set in Adobe Minion and Cronos multiple master typefaces e nga mana,e nga reo,e nga karangaranga maha tae noa ki nga Minita o te Karauna. ko tenei te honore,hei tuku atu nga moemoea o ratou i kawea te kaupapa nei. huri noa ki a ratou kua wheturangitia ratou te hunga tautoko i kokiri,i mau ki te kaupapa,mai te timatanga,tae noa ki te puawaitanga o tenei ripoata. ahakoa kaore ano ki a kite ka tangi,ka mihi,ka poroporoakitia ki a ratou. ki era o nga totara o Te-Wao-nui-a-Tane,ki a Te Makarini,ki a Horomona ma ki a koutou kua huri ki tua o te arai haere,haere,haere haere i runga i te aroha,me nga roimata o matou kua mahue nei. e kore koutou e warewaretia. ma te Atua koutou e manaaki,e tiaki ka huri Contents Letter of Transmittal _____________________________________________________xiii 1. Summary 1.1 Background ________________________________________________________1 1.2 Historical Claims ____________________________________________________4 1.3 Contemporary Claims ________________________________________________9 1.4 Preliminary Claims __________________________________________________11 1.5 Rekohu, the Chatham Islands, or Wharekauri? _____________________________12 1.6 Concluding Remarks ________________________________________________13 2. -

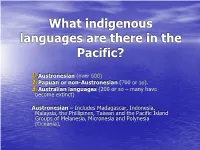

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

Health Care Professionals' Perceptions of Treatments for Co-Occurring Disorders

THE UTILIZATION OF A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TO CONDUCT A CONGRUENT ACULTURALLY UNIT Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu B.S., Brigham Young University, Hawaii, 2008 PROJECT Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in EDUCATION (Multicultural Education) at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO FALL 2010 THE UTILIZATION OF A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TO CONDUCT A CONGRUENT ACULTURALLY UNIT A Project by Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Forrest Davis, Ph.D. Date ii Student: Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. , Graduate Coordinator Dr. Maria Mejorado Date Department of Bilingual and Multicultural Education iii Abstract of THE UTILIZATION OF A QUALITATIVE RESEARCH TO CONDUCT A CONGRUENT ACULTURALLY UNIT by Lesieli Hingano Faaoso Tutuu This project was oriented towards a study of the emic worldview of the Tongan population in Sacramento. The data that was collected in this study was utilized as a frame of reference for the curriculum. The lesson plans in the project are based upon the Single Study approach in multicultural education. This approach was utilized because the members of the Tongan populations have specific educational needs to be addressed in the process of acculturation into American Society. __________________________________, Committee Chair Forrest Davis, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to say “MALO ‘AUPITO” to Dr. Forrest Davis for his continual encouragement, refining, and persistency in following up my project.