Laulōtaha; Tongan Perspectives of 'Quality' in Early Childhood Education Dorothy Lorraine Pau'uvale a Thesis Submitted To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maori & Pasifika Infants and Toddlers

Tangata Pasifika: Sustaining cultural knowledge and language competency for Pacific peoples. Presentation at the Victoria University Autumn Research Seminar, May 2018. Ali Glasgow Faculty of Education Language, culture, identity • A leai se gagana, ona leai lea o sa ta aganu’u, a leai la ta aganu’u ona po lea o le nu’u (Samoan proverb) • If there is no language, then there is no culture, • If there is no culture, then all of the village will be in darkness Presentation outline • My background • Pacific context • Aoteroa New Zealand context – culture, language • Research findings – Vuw Summer Scholarship (2015), TLRI ( Teaching and Learning Research Initiative, 2017). Ali – Kuki Airani – Tongareva Atoll Pacific perspectives • Pacific region located historically, contextually and geographically within Oceania, more particularly in the region of the Southern Pacific referred to as the Polynesian triangle (Ritchie & Ritchie, 1970) • ‘Our sea of islands ( Hau’ofa, 1993) Reclaiming & Reconceptualising Pacific Education • Pacific Education (currently) prioritises the voice and worldview of the outside which amputates our capacity for human agency. Within the Pacific the bulk of what we teach and learn in our schools and at our universities and colleges in the Pacific is what has been conceptualised and developed in and for the Western world (Koya-Vakauta,2016). • The indigenous peoples of the Pacific need to create their own pedagogy... rooted in Pacific values, assumptions, processes and practices ( Glasgow, 2010; Mara, Foliaki & Coxon, 1994; Tangatapoto,1984 & Taufe’ulungake, 2001). Aspiration Statement ( MOE, 2017, p.5) • Competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society. -

Celebration of the Niuean Language and Culture Ko E Tau Fakafiafiaaga

Celebration of the #pacificstars Niuean Language and Culture Ko e tau Fakafiafiaaga he Vagahau Niue mo e tau Aga Fakamotu Facts on Niue | Folafolaaga hagaaoia Population | Puke tagata ke he motu ko Niue In 2013 Niue peoples were the fourth largest Pacific • Niue is one of the world's largest coral islands. ethnic group in New Zealand making up 8.1% or 23,883 • Niue (pronounced “New-e (‘e’ as in ‘end’ – which means of New Zealand’s Pacific peoples’ population. 'behold the coconut') may be the world’s smallest The most common region this group lived in was the independent nation. Auckland Region (77.7 percent or 18,555 people), followed • The island is commonly referred to as "The Rock", by the Wellington Region (6.6 percent or 1,575 people), a reference to Niue being one of the biggest raised and the Waikato Region (4.3 percent or 1,038 people). coral islands in the world. The median age was 20.4 years. • The capital of Niuē is the village of Alofi. • Niueans are citizens of New Zealand. 78.9 percent (18,465 people) were born in New Zealand. • Niue is an elevated coral atoll with fringing coral reefs encircling steep limestone cliffs. It has a landmass of 259km and its highest point is about 60 metres In 2013 Niue peoples made up above sea level. • Niue lies 2400 km northeast of New Zealand 23,883 between Tonga, Samoa and the Cook Islands. of New Zealand's Pacific peoples' population History | Tau Tala Tu Fakaholo Polynesians from Samoa settled Niue around 900 AD. -

Gender & Interaction in a Globalizing World: Negotiating the Gendered

Chapter 13 Gender and interaction in a globalizing world: Negotiating the gendered self in Tonga* Niko Besnier 1. Gender and language in microscopic and macroscopic perspectives One of the more important developments in our understanding of the rela- tionship between language and gender in the last couple of decades is the recognition that the gendering of language is semiotically complex. Indeed, linguistic forms and practices do not define “women’s language” and “men’s language”, as earlier researchers argued (e.g., Lakoff 1975), but articulate with a host of social categories and processes that surround gen- der and help construct it. The clearest articulation of this position is Ochs’ (1992) demonstration that gendered linguistic practices are both indexical and indirect. Indexicality captures the insight that features of language (phonological, syntactic, discursive, etc.) “point to”, or suggest, gendered identities, and do not refer to gender in an unequivocal fashion, as linguistic symbols would. In this respect, the relationship between language and gen- der is no different from the relationship between language and any other aspect of socio-cultural identity, as we have known since the early days of sociolinguistics (Labov 1966a). However, the indexical linking of language and gender presents another layer of complexity: linguistic resources are semiotically connected to gender through the mediation of other aspects of the socio-cultural world. For example, features of language and interaction invoke social roles (e.g., mother, CEO, construction work), demeanors (e.g., politeness, authority, or the lack thereof), and activities (e.g., forms of work and play), all of which are in turn indexically associated with gender (see Figure 1). -

Samoan Research Methodology

VolumePacific-Asian 23 | Number Education 21 | 2011 Pacific-Asian Education The Journal of the Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Volume 23, Number 2, 2011 SPECIAL ISSUE Inside (and around) the Pacific Circle: Educational Places, Spaces and Relationships SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORS Eve Coxon The University of Auckland, New Zealand Airini The University of Auckland, New Zealand SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Elizabeth Rata The University of Auckland, New Zealand Diane Mara The University of Auckland, New Zealand Carol Mutch The University of Auckland, New Zealand EDITOR Elizabeth Rata, School of Critical Studies in Education, Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] EXECUTIVE EDITORS Airini, The University of Auckland, New Zealand Alexis Siteine, The University of Auckland, New Zealand CONSULTING EDITOR Michael Young, Institute of Education, University of London EDITORIAL BOARD Kerry Kennedy, The Hong Kong Institute of Education, Hong Kong Meesook Kim, Korean Educational Development Institute, South Korea Carol Mutch, Education Review Office, New Zealand Gerald Fry, University of Minnesota, USA Christine Halse, University of Western Sydney, Australia Gary McLean, Texas A & M University, USA Leesa Wheelahan, University of Melbourne, Australia Rob Strathdee, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand Xiaoyu Chen, Peking University, P. R. China Saya Shiraishi, The University of Tokyo, Japan Richard Tinning, University of Queensland, Australia ISSN 1019-8725 Pacific Circle Consortium for Education Publication design and layout: Halcyon Design Ltd, www.halcyondesign.co.nz Published by Pacific Circle Consortium for Education http://pacificcircleconsortium.org/PAEJournal.html Pacific-Asian Education Volume 23, Number 2, 2011 CONTENTS Editorial Eve Coxon 5 Articles Tala Mai Fafo: (Re)Learning from the voices of Pacific women 11 Tanya Wendt Samu Professional development in the Cook Islands: Confronting and challenging 23 Cook Islands early childhood teachers’ understandings of play. -

1 Bilingual Education in Aotearoa/New Zealand Richard Hill

Bilingual education in Aotearoa/New Zealand Richard Hill University of Waikato, New Zealand 1.1 Abstract Bilingual education in the New Zealand context is now over 30 years old. The two main linguistic minority groups involved in this type of education; the Indigenous Māori, and Pasifika peoples, of Samoan, Tongan, Cook Islands, Niuean and Tokelauan backgrounds have made many gains but have struggled in a national context where minority languages have low status. Māori bilingual programs are well established and have made a significant contribution towards reducing Māori language shift that in the 1970s looked to be beyond regeneration. Pasifika bilingual education by contrast is not widely available and not well resourced by the New Zealand government. Both forms continue to need support and a renewed focus at local and national levels. This chapter provides an overview of past development of Māori and Pasifika bilingual education and present progress. For Māori, the issues relate primarily to how to boost language regeneration, particularly between the generations. Gaining greater support for immersion programs and further strengthening bilingual education pedagogies, particularly relating to achieving biliteracy objectives, are key. In the Pasifika context, extending government and local support would not only safeguard the languages, but has the potential to counteract long-established patterns of low Pasifika student achievement in mainstream/English-medium schooling contexts. Finally, the future of both forms of bilingual education can be safeguarded if they are encompassed within a national languages policy that ensures minority language development in the predominantly English monolingual national context of New Zealand. 1 1.2 Introduction Aotearoa/New Zealand has two main bilingual education contexts, Māori and Pasifika.1 Both forms involve minority groups; the Māori language is the Indigenous language of Aotearoa/New Zealand, while the languages of the Pasifika people were brought to this country from the islands of Polynesia from the 1960s onwards. -

Pe Structure Cf Tongan Dance a Dissertation

(UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY P E STRUCTURE CF TONGAN DANCE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION CF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FUIFILDffiNT CF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE CF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ANTHROPOLOGY JUNE 1967 By _\G Adrienne L? Kaeppler Dissertation Committee: Alan Howard, Chairman Thomas W. Maretzki Roland W. Force Harold E. McCarthy Barbara B. Smith PREFACE One of the most conspicious features of Polynesian life and one that has continually drawn comments from explorers, missionaries, travelers, and anthropologists is the dance. These comments have ranged from outright condemnation, to enthusiastic appreciation. Seldom, however, has there been any attempt to understand or interpret dance in the total social context of the culture. Nor has there been any attempt to see dance as the people themselves see it or to delineate the structure of dance itself. Yet dance has the same features as any artifact and can thus be analyzed with regard both to its form and function. Anthropologists are cognizant of the fact that dance serves social functions, for example, Waterman (1962, p. 50) tells us that the role of the dance is the "revalidation and reaffirmation of the aesthetic, religious, and social values shared by a human society . the dance serves as a force for social cohesion and as a means to achieve the cultural continuity without which no human community can persist.” However, this has yet to be scientifically demonstrated for any Pacific Island society. In most general ethnographies dance has been passed off with remarks such as "various movements of the hands were used," or "they performed war dances." In short, systematic study or even satisfactory description of dance in the Pacific has been virtually neglected despite the significance of dance in the social relations of most island cultures. -

The Early LDS Missionaries: Teaching English and Converting Tongans.” by Haitelenisia Uhila I Am Indeed Humbled and Yet Honored to Be Here

The Early LDS Missionaries: Teaching English and Converting Tongans.” by Haitelenisia Uhila I am indeed humbled and yet honored to be here. I aim to teach English to my people someday, but I still struggle with the language because it is my second language. Anyway, I heard of this effort that the Tongan history people (‘Uho o Tonga) are doing and they’re trying to read the journals of the missionaries from Tonga and produce papers out of it, and my thought was, “I want to write something about my people,” Then I asked myself the question, “How were these LDS missionaries from the U.S. mainland, who spoke very little Tongan, able to teach Tongans English, a language which they knew very little or maybe nothing at all about and also how it influenced their conversion to the church, thus the topic of my presentation “The Early LDS Missionaries: Teaching English and Converting Tongans.” Before I go on I would like to read a story that was published in the Church News in 1959 that basically touches on all the things I want to talk about in my presentation—using one vehicle to get to another: Elder James R. Walker and Robert A. Smith were tired and hungry. Since morning they had walked from village from village on the Tongan island of Niuafo’ou, distributing tracts and conversing with the people. They had not eaten since leaving the ship that morning and had been unsuccessful in finding a place to spend the night. “You had better go to another village,” they had been told. -

Making a Case for Tongan As an Endangered Language

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Making a Case for Tongan as an provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Endangered Language Yuko Otsuka At fi rst glance, Tongan appears far from being endangered. It has nearly 100,000 speakers—remarkably sizable compared to other languages of Oceania—and is spoken in a predominantly monolingual and monocul- tural society.1 Furthermore, Tonga is an independent nation-state, in fact, the last kingdom in Polynesia. Why should one be talking at all about Tongan being endangered? This paper examines the linguistic situation in Tonga and argues that there are reasons to be concerned about the future of the Tongan language in the long run. The position put forward in this paper is as follows: In the postcolonial context, many instances of language endangerment should be defi ned in terms of a unit larger than a nation-state. Globalization has put small island nations like Tonga in a position such that, in order to survive, they are compelled to conform to the Western development model that is asso- ciated with English as a socioeconomically privileged language. Here, the term “globalization” refers to a particular aspect of the phenomenon, that is, interconnectedness facilitated by the expansion of Euro-American values. Interconnectedness certainly has benefi cial consequences, such as bringing new opportunities. Epeli Hau‘ofa, for example, has argued that it has empowered the peoples of Oceania, liberating them from the artifi cial boundaries imposed by nineteenth-century imperialism (1993, 10). The following discussion, however, focuses on the adverse effects of intercon- nectedness, especially as it affects language maintenance. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

Politics and Book Publishing in the Pacific Islands

University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Theses Collection University of Wollongong Year Politics and book publishing in the Pacific Islands Linda S. Crowl University of Wollongong Crowl, Linda S, Politics and book publishing in the Pacific Islands, PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2008. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/94 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/94 Politics and Book Publishing in the Pacific Islands A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from University of Wollongong by Linda S. Crowl BA (with Honors), Oberlin College MA, School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University School of History/Politics Faculty of Arts University of Wollongong June 2008 CERTIFICATION I, Linda S. Crowl, declare that this dissertation, submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the School of History/Politics, Faculty of Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Linda S. Crowl 10 June 2008 ii CONTENTS Certification ii Map, Figures, and Tables vi Abbreviations vii Glossary ix Abstract x Acknowledgements xii Map of the Pacific Islands xiv SECTION 1. BACKGROUND AND THEORY Chapter 1. Introduction 1 Geography, Societies, and Languages 1 History and Politics 2 Communication and Book Publishing -

FAUFAUA! an Introduction to Tongan Units Except Unit 10And20

an inTroducTion To TonGan Teachers’ Guide and supporT MaTerials learninG lanGuaGes series The heilala is the national flower of Tonga. A garland of heilala flowers, like the one shown on the cover, is a culturally significant gift. In this case, it welcomes teachers and learners to the Tongan language and confirms links with the Tongan language guidelines (TiNZC). Gifts of ngatu (tapa cloth) are also culturally important, so they are represented on the cover and in the design of this resource as well. When learners communicate successfully in Tongan, praise them, saying “Faufaua!” (Excellent! Well done!) Published 2010 for the Ministry of Education by CWA New Media, Box 19090, Wellington 6149, New Zealand. www.cwa.co.nz Publishing services by Lift Education, South Pacific Press Design services by ThinkSpace Design Illustrated by Scott Pearson Text copyright © Crown 2010 Illustrations copyright © Crown 2010 Music copyright © Crown 2010 All rights reserved. Enquiries should be made to the publisher. ISBN 978 0 478 34124 9 Further copies may be ordered from Ministry of Education Customer Services, freephone 0800 660 662, freefax 0800 660 663, by email: [email protected] or online at www.thechair.govt.nz Please quote item numbers as follows: Printed material only item number 119411 Complete resource item number 118307 conTenTs Talateu Preface 4 Lea Faka-Tonga The Tongan Language 20 Unit 1 Màlò e Lelei Greetings 23 Unit 2 Fakafe‘iloaki Introductions 48 Unit 3 Fàmili Family 74 Unit 4 Ko e Lokiako The Classroom 93 Unit 5 Lau Mata‘ifika´ -

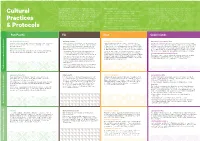

Cultural Practices & Protocols

Engagement that is meaningful is about respecting Advice may be about: By having a general understanding and knowing how to behave in these cultural practices and protocols. Pacific values common to • Formal ceremonies and knowing who and how to address situations shows Pacific communities respect and is a step in the right Cultural all Pacific Islands should always be considered when observing people and their roles in the appropriate manner direction for building good relationships. Below are a few examples any customs. However, among the different islands there are which demonstrate how practices vary from island to island. This is by • Use of island languages and translation by non-English speakers distinct differences in cultural practices, roles of family no means an exhaustive list but is merely intended to give you a basic Practices members, traditional dress and power structures. • Acknowledging and allowing time for elders to contribute introduction only. If you somehow forget everything you read here, • Taking time to observe protocols which uphold spirituality just remember to act respectfully and that it’s okay to ask if you don’t If you’re asked to attend a Pacific event or ceremony, through prayers. understand. it’s anticipated that you be accompanied and/or advised & Protocols by Pacific peoples who can help guide you. Note - A full list of basic greetings can be found at www.mpp.govt.nz - Tonga, Fiji and Samoa are the only Pacific countries that are commonly known for kava ceremony practices. Pan-Pacific Fiji Niue Cook Islands Role of spirituality in meetings Welcoming ceremony Welcoming ceremony and dance Haircutting ceremony (pakoti rouru) Pacific meetings or events usually begin and close with a prayer, and food is blessed Veiqaravi vakavanua is the traditional way to welcome an honoured guest Takalo was traditionally performed before going to war.