Languages of the World--Indo-Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plural Words in Austronesian Languages: Typology and History

Plural Words in Austronesian Languages: Typology and History A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Research Master of Arts in Linguistics by Jiang Wu Student ID: s1609785 Supervisor: Prof. dr. M.A.F. Klamer Second reader: Dr. E.I. Crevels Date: 10th January, 2017 Faculty of Humanities, Leiden University Table of contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................ iii Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iv List of tables ................................................................................................................... v List of figures ................................................................................................................ vi List of maps ................................................................................................................. vii List of abbreviations .................................................................................................. viii Chapter 1. Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 2. Background literature ................................................................................... 3 2.1. Plural words as nominal plurality marking ....................................................... 3 2.2. Plural words in Austronesian languages .......................................................... -

Hawaii Been Researched for You Rect Violation of Copyright Already and Collected Into Laws

COPYRIGHT 2003/2ND EDITON 2012 H A W A I I I N C Historically Speaking Patch Program ABOUT THIS ‘HISTORICALLY SPEAKING’ MANUAL PATCHWORK DESIGNS, This manual was created Included are maps, crafts, please feel free to contact TABLE OF CONTENTS to assist you or your group games, stories, recipes, Patchwork Designs, Inc. us- in completing the ‘The Ha- coloring sheets, songs, ing any of the methods listed Requirements and 2-6 waii Patch Program.’ language sheets, and other below. Answers educational information. Manuals are books written These materials can be Festivals and Holidays 7-10 to specifically meet each reproduced and distributed 11-16 requirement in a country’s Games to the individuals complet- patch program and help ing the program. Crafts 17-23 individuals earn the associ- Recipes 24-27 ated patch. Any other use of these pro- grams and the materials Create a Book about 28-43 All of the information has contained in them is in di- Hawaii been researched for you rect violation of copyright already and collected into laws. Resources 44 one place. Order Form and Ship- 45-46 If you have any questions, ping Chart Written By: Cheryle Oandasan Copyright 2003/2012 ORDERING AND CONTACT INFORMATION SPECIAL POINTS OF INTEREST: After completing the ‘The Patchwork Designs, Inc. Using these same card types, • Celebrate Festivals Hawaii Patch Program’, 8421 Churchside Drive you may also fax your order to Gainesville, VA 20155 (703) 743-9942. • Color maps and play you may order the patch games through Patchwork De- Online Store signs, Incorporated. You • Create an African Credit Card Customers may also order beaded necklace. -

Growing Plants for Hawaiian Lei ‘A‘Ali‘I

6 Growing Plants for Hawaiian Lei ‘a‘ali‘i OTHER COMMON NAMES: ‘a‘ali‘i kū range of habitats from dunes at sea makani, ‘a‘ali‘i kū ma kua, kū- level up through leeward and dry makani, hop bush, hopseed bush forests and to the highest peaks SCIENTIFIC NAME: Dodonaea viscosa CURRENT STATUS IN THE WILD IN HAWAI‘I: common FAMILY: Sapindaceae (soapberry family) CULTIVARS: female cultivars such as ‘Purpurea’ and ‘Saratoga’ have NATURAL SETTING/LOCATION: indigenous, been selected for good fruit color pantropical species, found on all the main Hawaiian Islands except Kaho‘olawe; grows in a wide Growing your own PROPAGATION FORM: seeds; semi-hardwood cuttings or air layering for selected color forms PREPLANTING TREATMENT: step on seed capsule to release small, round, black seeds, or use heavy gloves and rub capsules vigorously between hands; put seeds in water that has been brought to a boil and removed from heat, soak for about 24 hours; if seeds start to swell, sow imme- diately; discard floating, nonviable seeds; use strong rooting hormone on cuttings TEMPERATURE: PLANTING DEPTH: sow seeds ¼" deep in tolerates dry heat; tem- after fruiting period to shape or keep medium; insert base of cutting 1–2" perature 32–90°F short; can be shaped into a small tree or maintained as a shrub, hedge, or into medium ELEVATION: 10–7700' espalier (on a trellis) GERMINATION TIME: 2–4 weeks SALT TOLERANCE: good (moderate at SPECIAL CULTURAL HINTS: male and female CUTTING ROOTING TIME: 1½–3 months higher elevations) plants are separate, although bisex- WIND RESISTANCE: -

Ethnography of Ontong Java and Tasman Islands with Remarks Re: the Marqueen and Abgarris Islands

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 9, No. 3 July 1986 ETHNOGRAPHY OF ONTONG JAVA AND TASMAN ISLANDS WITH REMARKS RE: THE MARQUEEN AND ABGARRIS ISLANDS by R. Parkinson Translated by Rose S. Hartmann, M.D. Introduced and Annotated by Richard Feinberg Kent State University INTRODUCTION The Polynesian outliers for years have held a special place in Oceanic studies. They have figured prominently in discussions of Polynesian set- tlement from Thilenius (1902), Churchill (1911), and Rivers (1914) to Bayard (1976) and Kirch and Yen (1982). Scattered strategically through territory generally regarded as either Melanesian or Microne- sian, they illustrate to varying degrees a merging of elements from the three great Oceanic culture areas—thus potentially illuminating pro- cesses of cultural diffusion. And as small bits of land, remote from urban and administrative centers, they have only relatively recently experienced the sustained European contact that many decades earlier wreaked havoc with most islands of the “Polynesian Triangle.” The last of these characteristics has made the outliers particularly attractive to scholars interested in glimpsing Polynesian cultures and societies that have been but minimally influenced by Western ideas and Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 1 2 Pacific Studies, Vol. 9, No. 3—July 1986 accoutrements. For example, Tikopia and Anuta in the eastern Solo- mons are exceptional in having maintained their traditional social structures, including their hereditary chieftainships, almost entirely intact. And Papua New Guinea’s three Polynesian outliers—Nukuria, Nukumanu, and Takuu—may be the only Polynesian islands that still systematically prohibit Christian missionary activities while proudly maintaining important elements of their old religions. -

Micronesica 37(1) Final

Micronesica 37(1):163-166, 2004 A Record of Perochirus cf. scutellatus (Squamata: Gekkonidae) from Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands GARY J. WILES1 Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, 192 Dairy Road, Mangilao, Guam 96913, USA Abstract—This paper documents the occurrence of the gecko Perochirus cf. scutellatus at Ulithi Atoll in the Caroline Islands, where it is possibly restricted to a single islet. This represents just the third known location for the species and extends its range by 975 km. Information gathered to date suggests the species was once more widespread and is perhaps sensitive to human-induced habitat change. The genus Perochirus is comprised of three extant species of gecko native to Micronesia and Vanuatu and an extinct form from Tonga (Brown 1976, Pregill 1993, Crombie & Pregill 1999). The giant Micronesian gecko (P. scutellatus) is the largest member of the genus and was until recently considered endemic to Kapingamarangi Atoll in southern Micronesia, where it is common on many islets (Buden 1998a, 1998b). Crombie & Pregill (1999) reported two specimens resem- bling this species from Fana in the Southwest Islands of Palau; these are consid- ered to be P. cf. scutellatus pending further comparison with material from Kapingamarangi (R. Crombie, pers. comm.). Herein, I document the occurrence of P. cf. scutellatus from an additional site in Micronesia. During a week-long fruit bat survey at Ulithi Atoll in Yap State, Caroline Islands in March 1986 (Wiles et al. 1991), 14 of the atoll’s larger islets com- prising 77% of the total land area were visited. Fieldwork was conducted pri- marily from dawn to dusk, with four observers spending much of their time walking transects through the forested interior of each islet. -

LANGUAGE and STATE POWER CSUF Linguistics Colloquium the INEVITABLE RISE of MALAY October 30, 2020 the RISE of MALAY

Franz Mueller LANGUAGE AND STATE POWER CSUF Linguistics Colloquium THE INEVITABLE RISE OF MALAY October 30, 2020 THE RISE OF MALAY Historically, Malay began as the indigenous language of the eastern peat forest areas on the island of Sumatra. Today, Malay has grown into one of the largest languages in the world, with over 250 million users. Remarkable because Malay never was the largest language in the area (Javanese, Sundanese) nor was it centrally located. Inevitable because whenever it counted, there was no alternative. LANGUAGE SIZE: FACTORS Endangered languages: Factors that lead to endangerment (Brenzinger 1991) Discussion of factors that make a language large have focused on individual speaker choice Today’s point: Languages grow large primarily as a result of them being adopted & promoted by a powerful state Speaker take-up is an epiphenomenon of that. INSULAR SEA: THE MALAY ARCHIPELAGO MALAY VERSUS MALAYSIA Malaysia has 2 land masses: Northern Borneo “Dayak languages”: Iban, Kadazandusun, etc. “Malay peninsula” Aslian languages: Austroasiatic Coastal Borneo & Sumatra as the Malay homeland LANGUAGES OF SUMATRA INSULAR SEA AT THE START OF THE COLONIAL PERIOD Portuguese arrival 1509 in search of the spice islands They discovered that 1 language was understood across the archipelago: Malay Q:Why was this so? How did it get that way? What had made this language, Malay into the lingua franca of the archipelago long before the arrival of the Europeans? THE SPREAD OF BUDDHISM 1st century AD: Buddhism enters China 4th century AD: Buddhism was well established in China Monks and others travelling to India associated trade in luxury goods Monsoon wind patterns required months-long layovers in Sumatra early stop: port of Malayu (600s) (= the indigenous name of the Malay language) SRIVIJAYA Srivijaya (700s) [I-Ching (Yiching) 671] Buddhism. -

![Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2011-02128v1-cs-cl-4-nov-2020-234203.webp)

Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020

Cross-Lingual Machine Speech Chain for Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks Speech Recognition and Synthesis Sashi Novitasari1, Andros Tjandra1, Sakriani Sakti1;2, Satoshi Nakamura1;2 1Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan 2RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project AIP, Japan fsashi.novitasari.si3, tjandra.ai6, ssakti,[email protected] Abstract Even though over seven hundred ethnic languages are spoken in Indonesia, the available technology remains limited that could support communication within indigenous communities as well as with people outside the villages. As a result, indigenous communities still face isolation due to cultural barriers; languages continue to disappear. To accelerate communication, speech-to-speech translation (S2ST) technology is one approach that can overcome language barriers. However, S2ST systems require machine translation (MT), speech recognition (ASR), and synthesis (TTS) that rely heavily on supervised training and a broad set of language resources that can be difficult to collect from ethnic communities. Recently, a machine speech chain mechanism was proposed to enable ASR and TTS to assist each other in semi-supervised learning. The framework was initially implemented only for monolingual languages. In this study, we focus on developing speech recognition and synthesis for these Indonesian ethnic languages: Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks. We first separately train ASR and TTS of standard Indonesian in supervised training. We then develop ASR and TTS of ethnic languages by utilizing Indonesian ASR and TTS in a cross-lingual machine speech chain framework with only text or only speech data removing the need for paired speech-text data of those ethnic languages. Keywords: Indonesian ethnic languages, cross-lingual approach, machine speech chain, speech recognition and synthesis. -

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

Guest Experience

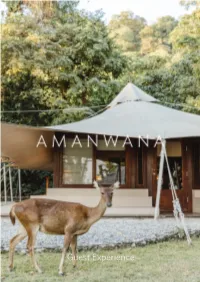

Guest Experience Contents The Amanwana Experience 3 Spa & Wellness 29 During Your Stay 5 Amanwana Spa Facilities 29 A New Spa Language 30 Aman Signature Rituals 32 Amanwana Dive Centre 7 Nourishing 33 Grounding 34 Diving at Amanwana Bay 7 Purifying 35 Diving at the Outer Reefs 8 Body Treatments 37 Diving at Satonda Island 10 Massages 38 Night Diving 13 Courses & Certifications 14 Moyo Conservation Fund 41 At Sea & On Land 17 Island Conservation 41 Species Protection 42 Water Sports 17 Community Outreach & Excursions 18 Camp Responsibility 43 On the Beach 19 Trekking & Cycling 20 Amanwana Kids 45 Leisure Cruises & Charters 23 Little Adventurers 45 Leisure Cruises 23 Fishing 24 Charters 25 Dining Experiences 27 Memorable Moments 27 2 The Amanwana Experience Moyo Island is located approximately eight degrees south of the equator, within the regency of Nusa Tenggara Barat. The island has been a nature reserve since 1976 and measures forty kilometres by ten kilometres, with a total area of 36,000 hectares. Moyo’s highest point is 600 meters above the Flores Sea. The tropical climate provides a year-round temperature of 27-30°C and a consistent water temperature of around 28°C. There are two distinct seasons. The monsoon or wet season is from December to March and the dry season from April to November. The vegetation on the island ranges from savannah to dense jungle. The savannah land dominates the plateaus and the jungle the remaining areas. Many varieties of trees are found on the island, such as native teak, tamarind, fig, coral and banyan. -

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

Indigenous Religion, Institutions and Rituals of the Mamanwas of Caraga Region, Philippines

Asian Journal of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities Vol. 1, No.1, 2013 INDIGENOUS RELIGION, INSTITUTIONS AND RITUALS OF THE MAMANWAS OF CARAGA REGION, PHILIPPINES Ramel D. Tomaquin College of Arts and Sciences Surigao del Sur State University Tandag City, Philippines Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Mamanwas, one of the IP communities of Caraga region. Said to be one of the original settlers of Caraga and considered the Negrito group of Mindanao. Only very few literatures and studies written about them. Despite of massive acculturation of other IP groups of the region such the Agusan-Surigao Manobos, the Mansaka/Mandaya, Banwaon, Higaanon and Talaandig. The Mamanwas still on the process of integration to Philippine body-politic. It is in this scenario they were able to retain indigenous religion, institutions and rituals. Thus the study was conducted. It covers on the following sites: Mt. Manganlo in Claver, Lake Mainit in Alegria both Surigao Del Norte, Hitaob in Tandag City, Lubcon and Burgus in Cortes and Sibahay in Lanuza of Surigao Del Sur respectively. The study used ethnographic method with strict adherence of the right of pre- informed consent in accordance with RA 8371 or Indigenous Peoples Right Act of 1997. It can be deduced from the paper that despite of socio- cultural changes of the IP’s of Caraga the Mamanwas were able to retain these practices but for how long? Moreover, socio-cultural change is slowly taking place in the Mamanwa social milieu. Preservation of these worldviews is wanting as a part of national heritage and for posterity. -

The Structure of the Toba Batak Conversation Hilman

Singapore THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS Hilman Pardede, Padang Sidempuan, May 25, 1960. He graduated from PressInternational English Program of North Sumatera THE STRUCTURE University in 1987. In the year of 1992 he took Magister Program in IKIP Malang, OF THE TOBA BATAK then he went to Doctoral Program in linguistics at North Sumatera University CONVERSATION in the year of 2007. In 2008, he attended a Sandwich Program in Aurbun THEBATAK CONVERSATION TOBA OF University, Alabama, USA. In 2010, he was a speaker in the International Seminar in Trang, Thailand. He presented a paper entitled “Adjecancy Pair in Toba STRUCTURE THE Batak”. HILMAN PARDEDE This book is about the structure of the Toba Batak Conversations. The structures are categorized as interaction and linguistics. The interaction structures are restricted to adjacency pairs and turn-taking, and the linguistic structure to phonological, grammatical and semantic completion point. There are some negative cases in the structure of Toba Batak conversations. These negative cases result from the Conversation HILMAN PARDEDE Analysis (CA) as a tool used to explain the interaction and linguistic structure in Toba Batak phenomena. ISBN: Singapore International Presss Singapore International Press 2012 THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS Hilman Pardede Singapore International Press 2012 THE STRUCTURE OF THE TOBA BATAK CONVERSATIONS By Hilman Pardede, Ph.D A Lecturer in English Language Teaching for Universitas HKBP Nommensen Pematangsiantar – Medan, Indonesia @Hilman Pardede, Ph.D ISBN: First Edition 2012 Singapore Do not circulate this book or any part of it in any binding or form by means of any equipment without any legal permission from Hilman Pardede, Ph.D! Prodeo et Patricia 2 For Lissa Donna Manurung and Claudia Benedita Pardede 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my deep gratitude to all those who lent their assistance and advice in the preparation and publication of this book.