Language Documentation and Description

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

Tüi Tüi Tuituiä Race Relations in 2010 Contact the Human Rights Commission

Tüi Tüi Tuituiä Race Relations in 2010 Contact the Human Rights Commission Human Rights Commission InfoLine If you have a human rights enquiry or discrimination complaint, call: 0800 496 877 (toll free) TXT 0210 236 4253 Fax 09 377 3593 (attn: InfoLine) Email [email protected] Language Line and New Zealand Sign Language interpreter available http://www.hrc.co.nz Tämaki Makaurau – Auckland Level 4 Tower Centre, 45 Queen Street (Cnr Queen and Customs Streets) PO Box 6751, Wellesley Street, Tämaki Makaurau/Auckland 1141 Waea/telephone 09 309 0874 Waea whakähua/fax 09 377 3593 Te Whanganui ä Tara – Wellington Level 1 Vector Building, 44-52 The Terrace PO Box 12411, Thorndon, Te Whanganui ä Tara/Wellington 6144 Waea/telephone 04 473 9981 Waea whakähua/fax 04 471 6759 Ötautahi – Christchurch Level 3 Guardian Assurance Building, 79-83 Hereford Street PO Box 1578, Christchurch/Ötautahi 8140 Waea/telephone 03 379 2015 Waea whakähua/fax 03 353 0959 Office of Human Rights Proceedings Te Tari Whakatau Take Tika Tangata Email [email protected] PO Box 6751, Wellesley Street, Auckland 1141 ISSN: 1178-7724 (PDF) ISSN: 1178-7716 (print) Published March 2011 Aotearoa New Zealand Cover art work: Race Relations Day poster 2011, People in harmony by blackrobindesign This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 New Zealand License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/nz/. This document has been printed on FSC Certified Mixed Source paper stock, manufactured using Elemental Chlorine Free pulp from Well Managed forests. -

A Languages Strategy for Auckland: Why and What Are the Issues?

A languages strategy for Auckland: Why and what are the issues? 4th International Conference on Language, Education and Diversity (LED 2015) Symposium: “A languages strategy for Auckland” 25 November 2015 Sharon Harvey (AUT) Susan Warren (COMET, Auckland) Hau Rawiri (COMET, Auckland) Jeff Johnstone (Asia New Zealand Foundation) Presentations • Developing an Auckland languages strategy • Sharon Harvey and Susan Warren • Te reo Māori as the pillar in an Auckland languages strategy • Hau Rawiri • The subject languages strand of the strategy • Jeff Johnstone Presentation 1: Developing an Auckland Languages Strategy 4th International Conference on Language, Education and Diversity (LED 2015) Symposium: “A languages strategy for Auckland” 25 November 2015 Sharon Harvey, AUT Susan Warren, COMET, Auckland History of national language policy in NZ • Maybe 45 years???? (Kaplan 1993/1994) • Aoteareo: Speaking for ourselves 1992 • Human Rights Commission - throughout 2000s • Royal Society of New Zealand - 2013 Discursively different move here was to link superdiversity with the need to have national level planning around language and culture across policy spectrum – not just in education field 1992 – Language Policy Framework Never adopted The Australian National Languages Policy 1987 (Lo Bianco 1987, 2002) • The overarching justifications of the NPL were expressed as four Es: • Enrichment: representing intellectual and cultural enrichment, for individuals and for the wider society; • Economics: facilitating trade and commercial relations, with a special emphasis on the Asian region, but not neglecting Europe and other parts of the world; • Equality: representing enhanced social and educational participation and opportunity for immigrant and indigenous communities and for speakers of non-standard varieties of English as well as for users of Australian Sign Language and for those students with language disabilities; • External: facilitating strategic responses to diplomatic, commercial and security interests. -

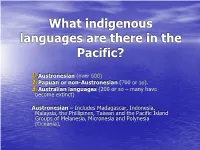

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

Granting Legal Personality to Te Reo Māori

1081 LET TE REO SPEAK: GRANTING LEGAL PERSONALITY TO TE REO MĀORI Tony Angelo* and Elisabeth Perham** Against the background of increasing concern about the future sustainability of te reo Māori, this article proposes, as one way to improve the prospects of the language, that te reo Māori be recognised as having legal personality. "Ko tōku nui, tōku wehi, tōku whakatiketike, tōku reo."1 (My language is my greatness, my inspiration, that which I hold precious). "Ko te reo te mauri o te mana Māori."2 (Language is the life force of Māori prestige). "If the language dies the culture will die, and something quite unique will have been lost to the world."3 I INTRODUCTION The importance of a language to the wellbeing of a people, to the maintenance of a culture's uniqueness and to a strong sense of identity cannot be overstated. * Professor of Law, Victoria University of Wellington. Māmari Stephens is to be credited with the idea for this article. Thanks are due to her for continued encouragement and support as the idea was developed. Kia ora Māmari. ** LLB(Hons), BA(Hons); Barrister and Solicitor of the High Court of New Zealand. 1 Te Ururoa Flavell MP "Flavell: Endangered Languages Conference" (XVI Foundation for Endangered Languages Conference – Language Endangerment in the 21st Century: Globalisation, Technology and New Media, AUT University, Auckland, 12 September 2012). 2 Sir James Henare (Waitangi Tribunal hearings on the Wai 11 claim, 24–28 June 1985). 3 Waitangi Tribunal Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the te Reo Māori Claim (Wai 11, 1986) [Wai 11 Report] at 1. -

Working with Maori Essential

Working with Māori Essential level learning module Published in September 2009 by Te Pou o Te Whakaaro Nui The National Centre of Mental Health Research, Information and Workforce Development. PO Box 108-244, Symonds Street, Auckland, New Zealand. ISBN 978-1-877537-32-5 Web www.tepou.co.nz/letsgetreal Email [email protected] 2 Working with Māori – Essential level Learning module – electronic version Contents Introduction ............................................................................................. 4 1 Working with Māori – prior experience ........................................................ 8 2 Pōwhiri: an interdependent process ........................................................... 9 3 The Treaty of Waitangi / Te Tiriti o Waitangi ............................................... 10 4 Te reo Māori ...................................................................................... 11 5 Tuakiri tangata................................................................................... 14 6 Tikanga Māori .................................................................................... 19 7 Whakawhanaunga................................................................................ 21 8 Hauora Māori ..................................................................................... 22 9 Manaaki ........................................................................................... 23 References and recommended reading ............................................................. 24 Learning Review -

Teachers of Additional Languages in New Zealand Schools, and Perceptions of Their Role, Place and Identity

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Teachers(of(additional(languages( in(New(Zealand(schools:(( A(national(survey(and(case(studies( A"thesis"presented"in"partial"fulfilment"of"the"" requirements"for"the"degree"of" Doctor"of"Philosophy" in" Applied"Linguistics" at"Massey"University,"Manawatu"Campus,"New"Zealand" Adèle"Jeannette"Scott" 2014" Abstract( While languages additional to the language of instruction have long been an established, non-compulsory part of the New Zealand secondary school curriculum, it was only in 2007 that they were given an official place as a learning area in the national curriculum. They do, however, remain non-compulsory. This study aims to investigate the background and profile of teachers of additional languages in New Zealand schools, and perceptions of their role, place and identity. In late 2008, teachers of additional languages at Years 1 to 13 were invited to complete a national online language teachers’ survey (NOLT08) (n=317). Two teachers of Spanish and one teacher of Japanese were invited to participate in individual case studies carried out across two school terms in 2010. Data were gathered through interviews and regular entries in a reflective e-log focusing on their situated experiences as teachers of additional languages together with their perceptions of their role and identity. Results of the NOLT08 survey confirmed that teachers of additional languages in New Zealand schools had different levels of qualifications and experiences depending on the sector in which they were teaching. -

The Phonemic Reality of Polynesian Vowel Length

The Phonetic Nature of Niuean * Vowel Length Nicholas Rolle University of Toronto In this paper, I argue that in Niuean, long vowels are underlying sequences of two qualitatively identical vowels, extending an analysis laid out in Taumoefolau (2002) on the related Tongic language Tongan. She argues that a long vowel will result predictably when stress falls on the first element of a double monophthong vowel sequence. Thus vowel length in these languages is a phonetic, not phonological, phenomenon. This account for vowel length is worked into an Optimality Theory (OT) framework, which crucially constrains RH- CONTOUR and ALL-FT-RIGHT above a constraint against double articulation, DIST(INCT). In addition, I provide a review of the literature concerning vowel length across Polynesian languages, and conclude that this analysis cannot be extended to all members of the Polynesian language family. 1. Introduction Across Polynesian languages, the presence of long vowels is uncontroversial, though whether these are only surface long vowels (i.e. phonetic) or underlying long vowels (i.e. phonemic) remains a contentious topic. In this paper, I outline an analysis of Tongan long vowels laid out in Taumoefolau (2002), and later supported by Anderson & Otsuka (2006), and extend this analysis to the related Tongic language Niuean. It is argued in Taumoefolau (2002) that Tongan long vowels are underlying identical vowel-vowel sequences (/ViVi/), whose surface manifestation is predictably a long vowel if stress falls on the first vowel of this sequence, and a double articulated vowel if stress falls on the second. This analysis is laid out in detail in section 3, preceded by a section describing some basic facts of Tongan phonology, and a review of the previous analyses of Tongan vowel length. -

In Ngāti Mutunga (1820 – 2019)

Nā te kōti i tatari: The inconsistent treatment of tikanga taurima (whāngai) in Ngāti Mutunga (1820 – 2019) Matiu Payne A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand 1 August, 2019. Acknowledgements He kura tangihia, he maimai aroha. Mākū ana te whenua i te roimata, i te auētanga o te whakaaro o te hunga kua whetūrangitia. Kei te mārama taku titiro atu ki maunga Taranaki ki maunga Pipitarawai me ō rāua taketake, ngā takotoranga whakamutunga o ōku huānga, o ōku kaumātua i riro atu ki te pō. Ko Joe Tapara, ko Charlene Tapara, ko Bob Goomes, ko Teresa Goomes rātou i ū ki ngā kaupapa Ngāti Mutunga ki Wharekauri. Ko rātou anō hoki ngā whenū o tōku korowai whakaruruhau i runga i tēnei huarahi mātauranga. Nō reira e ōku raukura, e ōku rauhuia, otirā e te rau o tītapu. E moe, e moe, e okioki. Mā ngā parirau whānui o te kākākura koutou e tauawhi i runga i tō koutou huarahi. Haere, haere, haere atu rā. Many supportive Ngāti Mutunga kaumātua have passed away during the course of this thesis. I spent many hours in discussion, with their warm company, and encouragement. Their knowledge of Ngāti Mutunga history and experiences were invaluable. I wish to acknowledge Uncle Joe and Aunty Goog (Charlene) Tapara, Aunty Teresa Goomes and Uncle Bob Goomes without whom the journey to completion of this PhD Thesis would have been arduous. In my own whānau, Aunty Linda Grennell and Uncle Graeme Grennell have joined our tūpuna (ancestors) throughout the duration of this thesis. -

Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori O Te Pae Tonga O Te Kuki Airani Also Known As Southern Cook Islands Māori

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. Editors: Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori SALLY AKEVAI NICHOLAS Cite this article: Sally Akevai Nicholas (2018). Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori. In Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. London: EL Publishing. pp. 36-64 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/160 This electronic version first published: July 2018 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori Sally Akevai Nicholas School of Language & Culture, Auckland University of Technology Language Name: Southern Cook Islands Māori Language Family: East Polynesian, Polynesian, Oceanic, Austronesian ISO 639-3 Code: rar Glottolog Code: raro1241 Number of speakers: ~15,000 - 20,2001 Location: 8-23S, 156-167W Vitality rating: EGIDS between 7 (shifting) and 8a (moribund) 1. -

1 Bilingual Education in Aotearoa/New Zealand Richard Hill

Bilingual education in Aotearoa/New Zealand Richard Hill University of Waikato, New Zealand 1.1 Abstract Bilingual education in the New Zealand context is now over 30 years old. The two main linguistic minority groups involved in this type of education; the Indigenous Māori, and Pasifika peoples, of Samoan, Tongan, Cook Islands, Niuean and Tokelauan backgrounds have made many gains but have struggled in a national context where minority languages have low status. Māori bilingual programs are well established and have made a significant contribution towards reducing Māori language shift that in the 1970s looked to be beyond regeneration. Pasifika bilingual education by contrast is not widely available and not well resourced by the New Zealand government. Both forms continue to need support and a renewed focus at local and national levels. This chapter provides an overview of past development of Māori and Pasifika bilingual education and present progress. For Māori, the issues relate primarily to how to boost language regeneration, particularly between the generations. Gaining greater support for immersion programs and further strengthening bilingual education pedagogies, particularly relating to achieving biliteracy objectives, are key. In the Pasifika context, extending government and local support would not only safeguard the languages, but has the potential to counteract long-established patterns of low Pasifika student achievement in mainstream/English-medium schooling contexts. Finally, the future of both forms of bilingual education can be safeguarded if they are encompassed within a national languages policy that ensures minority language development in the predominantly English monolingual national context of New Zealand. 1 1.2 Introduction Aotearoa/New Zealand has two main bilingual education contexts, Māori and Pasifika.1 Both forms involve minority groups; the Māori language is the Indigenous language of Aotearoa/New Zealand, while the languages of the Pasifika people were brought to this country from the islands of Polynesia from the 1960s onwards. -

Indigenous Language Revitalisation in Aotearoa New Zealand & Alba

Indigenous language revitalisation in Aotearoa New Zealand & Alba Scotland Catriona Elizabeth Timms (Kate Timms-Dean) A thesis submitted to the University of Otago in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. i 28 February 2013 1 Table of Contents List of Tables _________________________________________________________________ 5 List of Figures ________________________________________________________________ 5 List of Abbreviations ___________________________________________________________ 6 Glossary of Māori terms ________________________________________________________ 9 Glossary of Gàidhlig terms _____________________________________________________ 18 Mihimihi ___________________________________________________________________ 20 Acknowledgements ___________________________________________________________ 22 Abstract ____________________________________________________________________ 24 Introduction: Why revive endangered languages? __________________________________ 25 Defining Indigenous language revitalisation __________________________________ 27 Case Study 1: Te reo Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand __________________________ 32 Case Study 2: Gàidhlig in Alba Scotland ______________________________________ 38 Conclusion __________________________________________________________________ 45 1. Language Policy and Planning _________________________________________________ 52 What is language planning and language policy? ______________________________ 53 Why use language policy and planning in