In Ngāti Mutunga (1820 – 2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

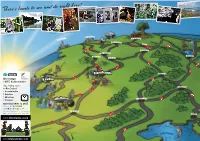

There's Loads to See and Do Right Here!

There’s loads to see and do right here! Ocean Beach : Kawhia Mangapohue Natural Bridge Te Puia Hot Springs : Kawhia Otorohanga Kiwi House Glowworms : Waitomo Spellbound Cave Ed Hillary Walkway : Otorohanga Kawhia Bay Marokopa Falls Black water rafting Otorohanga Kiwi House Hamilton land atamata ck M Au 1 ambrid C ge rau Ti 1 5 1 3 39 aru r t u u P amu w t u A e T toru Ro a ng iro ia P ik ih ih i K 1 5 39 3 31 ha 30 Otoro nga Tokoroa 31 Otorohanga 32 hia aw K i-SITE Visitor Centre FREE booking service m tia u A r i for New Zealand: 3 » Accommodation » Activities 37 1 » Attractions 30 Wi-Fi Hotspot angakino » Transport Waitomo M FREE PHONE: 0800 12 2665 Phone: 07 873 8951 [email protected] Centre of Maniapoto St, Otorohanga Kui e ti T [GPS location: 27 Turongo Street, Otorohanga] 30 Taupo www.otorohanga.co.nz 3 4 32 to New Plymouth to Taumarunui Lake Taupo www.kiwianatown.co.nz P Police Toilets Waitomo Otorohanga $ ATM/Bank Food/Dining Medical centre Otorohanga i-SITE Visitor Centre Free booking Train station Petrol station Centre of Maniapoto St, Otorohanga service for activities, Motel/Hotel [GPS location: 27 Turongo Street, Otorohanga] accommodation Camping FREE PHONE: 0800 12 2665 & travel Parking NZ-wide Mangapohue Natural Bridge Marokopa Falls & Piripiri Cave Phone: 07 873 8951 Oto’s friendly Otorohanga Wi-Fi Hotspot 24 [email protected] 23 W Ed Hillary Walkway (“Kiwiana” exhibits) 21 17 Otorohanga / Te Kuiti “Kiwiana Town” 1 i-SITE + Library 2 Otorohanga Kiwi House & Native Bird Park 20 16 39 37 Pirongia / Ngaruawahia / Auckland 22 3 Corrugated iron Kiwi sculpture (north) 4 Corrugated iron Kiwi sculpture (south) 18 5 St. -

The Native Land Court, Land Titles and Crown Land Purchasing in the Rohe Potae District, 1866 ‐ 1907

Wai 898 #A79 The Native Land Court, land titles and Crown land purchasing in the Rohe Potae district, 1866 ‐ 1907 A report for the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry (Wai 898) Paul Husbands James Stuart Mitchell November 2011 ii Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Report summary .................................................................................................................................. 1 The Statements of Claim ..................................................................................................................... 3 The report and the Te Rohe Potae district inquiry .............................................................................. 5 The research questions ........................................................................................................................ 6 Relationship to other reports in the casebook ..................................................................................... 8 The Native Land Court and previous Tribunal inquiries .................................................................. 10 Sources .............................................................................................................................................. 10 The report’s chapters ......................................................................................................................... 20 Terminology ..................................................................................................................................... -

12 GEO V 1921 No 64 Waikato and King-Country Counties

604 1~21, No. 64.J Waikato and King-country Oounties. [12 GEO. V. New Zealand. Title. ANALYSIS. 1. Short Title and commencement. 10. Boundaries of Raglan County altered. 2. Act deemed to be a special Act. 11. Boundaries of Waikato County altered. 3. Otorohanga County constituted. 12. Boundaries of Piako County altered. 4. Taumarunui County constituted. 13. Boundaries of Waipa County altered. 5. Application of Counties Act, 1920. 14. Taupo East and Taupo West Counties united. 6. Awakino and Waitomo Counties abolished, and 15. Road districts abolished. Waitomo County constituted. 16. Taupo Road District constituted. 7. Antecedent liabilities of Awakino and Wal 17. Application of provisions of Counties Act, 1920, tomo County C,ouncils to be antecedent in respect of alterations of boundaries. liability of new Waitomo County. 18. Temporary provision for control of certain 8. System ,of rating in Waitomo County. districts. 9. Boundaries of Kawhia County altered. Schedules. 1921-22, No. 64 . Title .AN ACT to give Effect to the Report of the Commission appointed under Section Ninety-one of the Reserves and other Lands Disposal and Public Bodies Empowering Act, 1920. [11th February, 1922. BE IT ENACTED by the General Assembly of New Zealand in Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows :- Short Title and 1. This Act may be cited as the Waikato and King-country commencement. Counties Act, 1921-22, and shall come into operation on the :o/st day of April, nineteen hundred and twenty-two. Act deemed to be a 2. This Act shall be deemed to be a special Act within the special Act. -

Kaihu Valley and the Ripiro West Coast to South Hokianga

~ 1 ~ KAIHU THE DISTRICT NORTH RIPIRO WEST COAST SOUTH HOKIANGA HISTORY AND LEGEND REFERENCE JOURNAL FOUR EARLY CHARACTERS PART ONE 1700-1900 THOSE WHO STAYED AND THOSE WHO PASSED THROUGH Much has been written by past historians about the past and current commercial aspects of the Kaipara, Kaihu Valley and the Hokianga districts based mostly about the mighty Kauri tree for its timber and gum but it would appear there has not been a lot recorded about the “Characters” who made up these districts. I hope to, through the following pages make a small contribution to the remembrance of some of those main characters and so if by chance I miss out on anybody that should have been noted then I do apologise to the reader. I AM FROM ALL THOSE WHO HAVE COME BEFORE AND THOSE STILL TO COME THEY ARE ME AND I AM THEM ~ 2 ~ CHAPTERS CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY CHARACTERS NAME YEAR PLACE PAGE Toa 1700 Waipoua 5 Eruera Patuone 1769 Northland 14 Te Waenga 1800 South Hokianga 17 Pokaia 1805 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 30 Murupaenga 1806 South Hokianga – Ripiro Coast 32 Kawiti Te Ruki 1807 Ahikiwi – Ripiro Coast 35 Hongi Hika 1807 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 40 Taoho 1807 Kaipara – Kaihu Valley 44 Te Kaha-Te Kairua 1808 Ripiro Coast 48 Joseph Clarke 1820 Ripiro Coast 49 Samuel Marsden 1820 Ripiro Coast 53 John Kent 1820 South Hokianga 56 Jack John Marmon 1820 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 58 Parore Te Awha 1821 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 64 John Martin 1827 South Hokianga 75 Moetara 1830 South Hokianga - Waipoua 115 Joel Polack -

DECLINED APPLICATIONS 1St April 2014 to 28Th February 2015 Action

DECLINED APPLICATIONS 1st April 2014 to 28th February 2015 Action Education Incorporated Accelerating Aotearoa Inc Acting Up Addington Harness Hall of Fame Charitable Trust Adult Literacy Trust Age Concern New Zealand Inc Age Concern Wanganui Inc Age Concern Wellington Inc Age Concern Whangarei Inc Ahipara School Board of Trustees Alhambra-Union Rugby Football Club Inc Alzheimers New Zealand Inc Antara Association Inc Argo Trust Aspire Incorporated Aspiring Gymsports Incorporated Assistance Dogs New Zealand Asthma New Zealand - Asthma South Canterbury Athletics Canterbury Cross Country & Road Committee Auckland Archery Club Inc Auckland Basketball Services Ltd Auckland Coastguard Incorporated Auckland Deaf Society Inc Auckland District Kidney Society Inc Auckland Down Syndrome Assn Auckland Festival Trust Auckland Grammar School Auckland Hockey Assn Auckland Netball Centre Inc Auckland Regional Rescue Helicopter Trust Auckland Rugby League Referees Assn Inc Auckland Tuhoe Society Incorporated T/A Te Tira Hou Marae Auckland University Engineering Sports Club Auckland Youth Orchestra Inc Autism New Zealand Inc Avonside Early Childhood Centre Awatere Playcentre Basketball New Zealand Inc Bayfield High School Beaconsfield School PTA Beat Bowel Cancer Aotearoa Incorporated Bhartiya Samaj Charitable Trust Big Brothers Big Sisters of Taranaki Blockhouse Bay Bowls Inc Blockhouse Bay Primary School Body Positive Incorporated - Wellington Brass Band Association of New Zealand Inc Broken River Ski Club Inc Bruce McLaren Intermediate School Buller -

Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage

束 9mm Proceedings ISBN : 978-4-9909775-1-1 of the International Researchers Forum: Perspectives Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage IRCI Proceedings of International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society 17-18 December 2019 Tokyo Japan Organised by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Agency for Cultural Affairs, Japan Co-organised by Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, National Institutes for Cultural Heritage Published by International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI), National Institutes for Cultural Heritage 2 cho, Mozusekiun-cho, Sakai-ku, Sakai City, Osaka 590-0802, Japan Tel: +81 – 72 – 275 – 8050 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.irci.jp © International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) Published on 10 March 2020 Preface The International Researchers Forum: Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage towards a Sustainable Society was organised by the International Research Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region (IRCI) in cooperation with the Agency for Cultural Affairs of Japan and the Tokyo National Research Institute for Cultural Properties on 17–18 December 2019. -

And Did She Cry in Māori?”

“ ... AND DID SHE CRY IN MĀORI?” RECOVERING, REASSEMBLING AND RESTORYING TAINUI ANCESTRESSES IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND Diane Gordon-Burns Tainui Waka—Waikato Iwi A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History The University of Canterbury 2014 Preface Waikato taniwha rau, he piko he taniwha he piko he taniwha Waikato River, the ancestral river of Waikato iwi, imbued with its own mauri and life force through its sheer length and breadth, signifies the strength and power of Tainui people. The above proverb establishes the rights and authority of Tainui iwi to its history and future. Translated as “Waikato of a hundred chiefs, at every bend a chief, at every bend a chief”, it tells of the magnitude of the significant peoples on every bend of its great banks.1 Many of those peoples include Tainui women whose stories of leadership, strength, status and connection with the Waikato River have been diminished or written out of the histories that we currently hold of Tainui. Instead, Tainui men have often been valorised and their roles inflated at the expense of Tainui women, who have been politically, socially, sexually, and economically downplayed. In this study therefore I honour the traditional oral knowledges of a small selection of our tīpuna whaea. I make connections with Tainui born women and those women who married into Tainui. The recognition of traditional oral knowledges is important because without those histories, remembrances and reconnections of our pasts, the strengths and identities which are Tainui women will be lost. Stereotypical male narrative has enforced a female passivity where women’s strengths and importance have become lesser known. -

Tüi Tüi Tuituiä Race Relations in 2010 Contact the Human Rights Commission

Tüi Tüi Tuituiä Race Relations in 2010 Contact the Human Rights Commission Human Rights Commission InfoLine If you have a human rights enquiry or discrimination complaint, call: 0800 496 877 (toll free) TXT 0210 236 4253 Fax 09 377 3593 (attn: InfoLine) Email [email protected] Language Line and New Zealand Sign Language interpreter available http://www.hrc.co.nz Tämaki Makaurau – Auckland Level 4 Tower Centre, 45 Queen Street (Cnr Queen and Customs Streets) PO Box 6751, Wellesley Street, Tämaki Makaurau/Auckland 1141 Waea/telephone 09 309 0874 Waea whakähua/fax 09 377 3593 Te Whanganui ä Tara – Wellington Level 1 Vector Building, 44-52 The Terrace PO Box 12411, Thorndon, Te Whanganui ä Tara/Wellington 6144 Waea/telephone 04 473 9981 Waea whakähua/fax 04 471 6759 Ötautahi – Christchurch Level 3 Guardian Assurance Building, 79-83 Hereford Street PO Box 1578, Christchurch/Ötautahi 8140 Waea/telephone 03 379 2015 Waea whakähua/fax 03 353 0959 Office of Human Rights Proceedings Te Tari Whakatau Take Tika Tangata Email [email protected] PO Box 6751, Wellesley Street, Auckland 1141 ISSN: 1178-7724 (PDF) ISSN: 1178-7716 (print) Published March 2011 Aotearoa New Zealand Cover art work: Race Relations Day poster 2011, People in harmony by blackrobindesign This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 New Zealand License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/nz/. This document has been printed on FSC Certified Mixed Source paper stock, manufactured using Elemental Chlorine Free pulp from Well Managed forests. -

First Years at Hokianga 1827 – 1836

First Years at Hokianga 1827-1836 by Rev.C.H.Laws FIRST YEARS AT HOKIANGA 1827 – 1836 In a previous brochure, entitled "Toil and Adversity at Whangaroa," the story of the Methodist Mission to New Zealand is told from its initiation in 1823 to its disruption and the enforced flight of the missionaries in 1827. After a brief stay with members of the Anglican Mission at the Bay of Islands the Methodist party sailed for Sydney in the whaler "Sisters" on January 28th, 1827, arriving at their destination on February 9th. It consisted of Nathaniel Turner and Mrs. Turner, with their three children, John Hobbs, James Stack and Mr. and Mrs. Luke Wade, and they took with them a Maori girl and two native lads. William White had left Whangaroa for England on September 19th, 1825, and at the time of the flight had not returned. The catastrophe to the Mission was complete. The buildings had been burned to the ground, the live stock killed; books and records destroyed, and the property of the Mission now consisted only of a few articles in store in Sydney which had not been forwarded to New Zealand. Wesley Historical Society (NZ) Publication #4(2) 1943 Page 1 First Years at Hokianga 1827-1836 by Rev.C.H.Laws Chapter I The departure of the Mission party for Sydney is seen, as we look back upon it, to have been the right course. Sydney was their headquarters, they were a large party and could not expect to stay indefinitely with their Anglican friends, and it could not be foreseen when they would be able to re-establish the work. -

A Languages Strategy for Auckland: Why and What Are the Issues?

A languages strategy for Auckland: Why and what are the issues? 4th International Conference on Language, Education and Diversity (LED 2015) Symposium: “A languages strategy for Auckland” 25 November 2015 Sharon Harvey (AUT) Susan Warren (COMET, Auckland) Hau Rawiri (COMET, Auckland) Jeff Johnstone (Asia New Zealand Foundation) Presentations • Developing an Auckland languages strategy • Sharon Harvey and Susan Warren • Te reo Māori as the pillar in an Auckland languages strategy • Hau Rawiri • The subject languages strand of the strategy • Jeff Johnstone Presentation 1: Developing an Auckland Languages Strategy 4th International Conference on Language, Education and Diversity (LED 2015) Symposium: “A languages strategy for Auckland” 25 November 2015 Sharon Harvey, AUT Susan Warren, COMET, Auckland History of national language policy in NZ • Maybe 45 years???? (Kaplan 1993/1994) • Aoteareo: Speaking for ourselves 1992 • Human Rights Commission - throughout 2000s • Royal Society of New Zealand - 2013 Discursively different move here was to link superdiversity with the need to have national level planning around language and culture across policy spectrum – not just in education field 1992 – Language Policy Framework Never adopted The Australian National Languages Policy 1987 (Lo Bianco 1987, 2002) • The overarching justifications of the NPL were expressed as four Es: • Enrichment: representing intellectual and cultural enrichment, for individuals and for the wider society; • Economics: facilitating trade and commercial relations, with a special emphasis on the Asian region, but not neglecting Europe and other parts of the world; • Equality: representing enhanced social and educational participation and opportunity for immigrant and indigenous communities and for speakers of non-standard varieties of English as well as for users of Australian Sign Language and for those students with language disabilities; • External: facilitating strategic responses to diplomatic, commercial and security interests. -

Page Auē Le Oti: Samoan Death Rituals in a New Zealand Context. Abstract

Auē le oti: Samoan death rituals in a New Zealand context. Byron Malaela Sotiata Seiuli1 University of Waikato Abstract Given that dialogue relating to death and grief for many Samoans still remains in the realm of tapu (sacred) or sā (protected), few attempts have been made by researchers of Samoan heritage to understand whether the cultural contexts for enacting associated rituals might also provide avenues for healing. Psychological scholarship on recovery following death, particularly among men, is largely based on dominant western perspectives that continue to privilege both clinical and ethnocentric perspectives as the norm. This case presentation, which forms part of a larger doctoral research by the author, demonstrates that some Samoan end-of-life rituals opens space for greater consideration of recovery from death as a culturally-defined process. In many instances, instead of severing ties with the deceased person as is popular in clinical approaches to grief work, Samoan grief resolution strongly endorses continued connections through its mourning patterns. Their end-of-life enactment helps to transition the deceased from this life to the next, while drawing the living together. Critically, the performance and maintenance of such important tasks create space for heaving emotions to be calmed, where meaning is made, and where the lives of those impacted are slowly restored. Some of these familiar rituals offer therapeutic value, enabling Samoans involved in this study to walk hand-in-hand with their emotional distress, while -

The Parikino Block Claim

Wai 903, #A22 OFFICIAL RESEARCH REPORT ON THE PARI KINO BLOCK CLAIM WAI 214 Tom Bennion 18 February 1994 Parikino research report 2 Scope of the Research Thi s report is the resul t of one week I s research of the documentary material available and several days writing Up.l The research included a one day visit to the offices of the Maori Land Court and Maori Trustee in Wanganui. I have viewed many of the original land court minutes and files relating to this block and its subdivisions (I was greatly aSSisted by the claimants who provided many papers from the block files and a Maori Trustee file). I have concentrated in particular on subdivision number 7, where, as the evidence shows, urupa are located. I have, in the time available, been able to view many, but by no means all of the relevant papers, and I note below areas which might reward further research. I believe however that the material viewed so far does allow some preliminary conclusions to be drawn about events in this block and the movement of the land out of the hands of the original Maori owners. Research Credentials My name is Thomas Hugh Bennion. In 1987 I graduated from the Victoria University of Wellington with a Bachelor of Laws with honours and a Bachelor of Arts, majoring in history. In 1986-88 I worked part-time as a researcher for the Law Commission on the production of the Commission report The Treaty of Waitangi and Maori Fisheries. Mataitai: Nga Tikanga Maori Me Te Tiriti 0 Waitangi.