Perspectives of Research for Intangible Cultural Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

978-1-4964-4748-7.Pdf

The Tyndale nonfiction imprint Visit Tyndale online at tyndale.com. Visit Tyndale Momentum online at tyndalemomentum.com. TYNDALE, Tyndale’s quill logo, Tyndale Momentum, and the Tyndale Momentum logo are registered trademarks of Tyndale House Ministries. Tyndale Momentum is the nonfiction imprint of Tyndale House Publishers, Carol Stream, Illinois. The Lord of the Rings is a trademark of the Saul Zaentz Company dba Tolkien Enterprises. Finding God in The Lord of the Rings Copyright © 2001 by Kurt Bruner; copyright © 2021 by Kurt Bruner and Jim Ware. All rights reserved. Cover illustration by Lindsey Bergsma. Copyright © Tyndale House Ministries. All rights reserved. Designed by Lindsey Bergsma Edited by Lisa A. Jackson All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version,® NIV.® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scripture quotations marked KJV are taken from the Holy Bible, King James Version. Scripture quotations marked NASB are taken from the New American Standard Bible,® copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. Scripture quotations marked NLT are taken from the Holy Bible, New Living Translation, copyright © 1996. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers, Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked NKJV are taken from the New King James Version,® copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All -

Exploring the Arts of Japan from Antiquity to the Present

124TH year | no. 43,036 IssN 0289-1956 © THe JaPaN TIMes, LTd., 2020 saTurday, MARCH 14, 2020 Japan Cultural Expo Exploring the Arts of Japan from Antiquity to the Present NORIO KIDERA Bando Kamezo performs a scene from “Sugawara Denju Tenarai Kagami.” Kagami.” Bando performs “Sugawara Kamezo scene a Denju from Tenarai COLLECTION OF SHIRIAGARI KOTOBUKI SHIRIAGARI OF COLLECTION Head Office: 14F Kioicho Bldg., 3-12 Kioicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo Advertising (Crossmedia) Tel: 050-3646-8421 Email: [email protected] Web: www.japantimes.co.jp B2 | The Japan Times | Saturday, March 14, 2020 MAJOR PROGRAMS (Sponsored content) Late March to June 1, 2020 EXPLORE 10,000 YEARS Timeless Conversations 2020: OF CULTURAL PRACTICES Voices from Japanese Art of the Past and Present ttracted to Japanese paintings like we would like to create and offer more and those of artist Katsushika Hokusai? more experience-based programs,’’ said Yumi ACurious about ancient techniques for Ennyu, director general of the Japan Cultural This unique exhibition will shed an entirely wooden architecture or the works of famous Expo. new light on Japanese art through a com- modern architects such as Kenzo Tange and Co-sponsored by the Agency for Cultural parison of classic and contemporary art- Kengo Kuma? Affairs and the Japan Arts Council, the expo works. Pre-20th century pieces including The Japan Cultural Expo, a series of art and features art works across different genres, paintings, Buddhist statues, pottery and cultural programs across Japan, will go into full including pottery, ukiyo-e paintings, kimono, swords will be paired with artworks by eight gear this year. -

Jawa Tengah Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta

110?0'0"E 110?12'0"E 110?24'0"E 110?36'0"E 110?48'0"E 111?0'0"E WINDUSARI SECANG SIMO KARANGMALANG Mt. Merbabu BabadanNOGOSARI Tempuredj KALIWUNGU PLUPUH KALIWIRO KALIANGKRIK Magelang JAWA TENGAH AMPEL SAMBI KALIJAMBE SAPURAN BANDONGAN TEGALREJO MASARAN SRAGEN PAKIS GONDANGREJO KEDAWUNG WONOSOBO MAGELANG SELATAN Banjumari SELO Ranousari CEPOGO NGEMPLAK Djambangan CANDIMULYO SAWANGAN BOYOLALIBojolali KEBAKKRAMAT KEPIL KAJORAN Gatakan Mt. Merapi COLOMADUBANJARSARI WADASLINTANG BANYUDONO KERJO MARTOYUDAN DUKUN TERAS JEBRES TEMPURAN BOYOLALI Kartosuro MOJOGEDANG MAGELANGMUNTILAN KARTASURA MUSUK MOJOSONGO LAWEYAN Surakarta TASIKMADU BRUNO Broena SRUMBUNG SAWIT JATEN PASAR KLIWON KARANGANYAR GATAK SALAMAN Balaboedoer Srumbung TULUNG SERENGAN PITURUH MOJOLABAN BENER MUNGKID KARANGANYAR Bener KEMALANG POLANHARJO KARANGPANDAN 7?36'0"S 7?36'0"S SALAM WONOSARI BAKI GROGOL GEBANG BOROBUDUR TURI CANGKRINGAN Bandjarsari DELANGGU Pablengan JATINOM MATESIH KEMIRI Bedojo Pangkalan POLOKARTO NGLUWAR KARANGANOM PAKEM SUKOHARJO JUMANTONO TEMPEL KARANGNONGKONGAWEN JUWIRING Kemiri LOANO Kaliredjo Bangsri Koeangsan MANISRENGGO CEPER BENDOSARI KALIBAWANGSAMIGALUH SLEMAN KLATEN SLEMAN PEDAN SUKOHARJO Purworedjo Purworejo NGAGLIK NGEMPLAK KEBONARUM Klaten KARANGDOWO JUMAPOLO PURWOREJOBAYAN Sleman PURWOREJO JOGONALAN KALIKOTES KUTOARJO KALIGESING SEYEGAN TAWANGSARI Belang MINGGIR PRAMBANANKLATEN SELATAN TRUCUK BUTUH MLATI NGUTER NANGGULAN KALASAN KLATEN TENGAH Cawas Karangasem JATIPURO Purworejo Kutu Kalasan BANYU URIP Naggulan CAWAS GODEAN DEPOK WEDI MOYUDAN JETIS -

![Oceania Is Us:” an Intimate Portrait of Chamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from Unincorporated Territory: [Lukao]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6169/oceania-is-us-an-intimate-portrait-of-chamoru-identity-and-transpacific-solidarity-in-from-unincorporated-territory-lukao-296169.webp)

Oceania Is Us:” an Intimate Portrait of Chamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from Unincorporated Territory: [Lukao]

The Criterion Volume 2020 Article 8 6-18-2020 “Oceania is Us:” An Intimate Portrait of CHamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from unincorporated territory: [lukao] Maressa Park College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/criterion Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, Pacific Islands Languages and Societies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Park, Maressa (2020) "“Oceania is Us:” An Intimate Portrait of CHamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from unincorporated territory: [lukao]," The Criterion: Vol. 2020 , Article 8. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/criterion/vol2020/iss1/8 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Criterion by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. 1 Park The Criterion 2019–2020 “Oceania is Us:” An Intimate Portrait of CHamoru Identity and Transpacific Solidarity in from unincorporated territory: [lukao] Maressa Park College of the Holy Cross Class of 2022 uam, or Guåhan in the CHamoru language, holds a history of traumatic and unresolved militarization imposed by several countries including G the United States. From 1521 to 1898, Spain colonized Guåhan and inflicted near-total genocide (Taimanglo). From 1898 to 1941, the occupier became the United States, which inflicted its own trauma — until 1941, when Japanese forces attacked and occupied the island (Taimanglo). In 1944, the United States attacked the island once more, gaining control over the island and eventually deeming it an “unincorporated territory” — which poet and author Dr. -

Shiraoi, Hokkaido New Chitose Airport Uaynukor Kotan Upopoy National Ainu Museum and Park

Services ◆ Multilingual support (up to 8 languages: Ainu, Japanese, English, Chinese ◆Barrier-free access [Traditional and Simplified], Korean, Russian and Thai) ◆ Free Wi-Fi Shops and restaurants (cashless payment accepted) Entrance Center Entrance Center Shop National Ainu Museum Shop Restaurant and Food Court The restaurant has a view The shop has original Upopoy The shop carries Ainu crafts, 出ア 会 う イ 場 ヌ 所 の 。 世 界 と overlooking Lake Poroto, and goods, Ainu crafts, Hokkaido original museum merchandise, the food court is a casual space souvenirs, snacks, and various and books. Visitors can purchase where visitors can choose from a everyday items. drinks and relax to enjoy the variety of dishes. view overlooking Lake Poroto. ◆Hours: 9:00am to Upopoy closing time ◆Hours: 9:00am to Upopoy closing time Discover Ainu Culture Dates and Hours (April 2021 to March 2022) Period Hours April 1 to July 16 Weekdays: 9:00am to 6:00pm August 30 to October 31 Weekends/national holidays: 9:00am to 8:00pm July 17 to August 29 9:00am to 8:00pm November 1 to March 31 9:00am to 5:00pm * Closed on Mondays (If Monday is a holiday, closed on the next business day) and from December 29 to January 3 Admission (tax included) General visitors Group visitors (20 or more) Adult 1,200 yen 960 yen High school student (16 to 18) 600 yen 480 yen Junior high school student and younger (15 and under) Free Free * Admission tickets to museum and park (excluding special exhibitions at museum and hands-on activities) * In Japan, most students attend high school from age 16 to 18. -

Perlindungan Hak Cipta Atas Motif Batik Sebagai Warisan Budaya Bangsa (Studi Terhadap Karya Seni Batik Tradisional Kraton Surakarta)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diponegoro University Institutional Repository PERLINDUNGAN HAK CIPTA ATAS MOTIF BATIK SEBAGAI WARISAN BUDAYA BANGSA (STUDI TERHADAP KARYA SENI BATIK TRADISIONAL KRATON SURAKARTA) TESIS Disusun Dalam Rangka Memenuhi Persyaratan Program Magister Ilmu Hukum Oleh : Rindia Fanny Kusumaningtyas, SH B4A 007 100 Pembimbing : Dr. BUDI SANTOSO, S.H., MS PROGRAM MAGISTER ILMU HUKUM PROGRAM PASCASARJANA UNIVERSITAS DIPONEGORO SEMARANG 2009 HALAMAN PENGESAHAN PERLINDUNGAN HAK CIPTA ATAS MOTIF BATIK SEBAGAI WARISAN BUDAYA BANGSA (STUDI TERHADAP KARYA SENI BATIK TRADISIONAL KRATON SURAKARTA) TESIS Diajukan untuk memenuhi syarat-syarat guna memperoleh gelar Magister Ilmu Hukum pada Program Pasca Sarjana Universitas Diponegoro Oleh : Rindia Fanny Kusumaningtyas, SH NIM. B4A 007 100 Tesis dengan judul di atas telah disahkan dan disetujui untuk diperbanyak Mengetahui, Pembimbing Ketua Program Magister Ilmu Hukum Dr. Budi Santoso, S.H., MS Prof. Dr. Paulus Hadisuprapto, S.H., MH NIP. 131 631 876 NIP. 130 531 702 HALAMAN PENGUJIAN PERLINDUNGAN HAK CIPTA ATAS MOTIF BATIK SEBAGAI WARISAN BUDAYA BANGSA (STUDI TERHADAP KARYA SENI BATIK TRADISIONAL KRATON SURAKARTA) Disusun Oleh : RINDIA FANNY KUSUMANINGTYAS, SH NIM. B4A 007 100 Dipertahankan di depan Dewan Penguji Pada tanggal 25 Maret 2009 Tesis ini telah diterima sebagai persyaratan untuk memperoleh gelar Magister Ilmu Hukum Mengetahui, Pembimbing Ketua Program Magister Ilmu Hukum Dr. Budi Santoso, S.H., MS Prof. Dr. Paulus Hadisuprapto, S.H., MH NIP. 131 631 876 NIP. 130 531 702 KATA PENGANTAR Puji Syukur Kehadiratan Tuhan Yang Maha Kuasa atas rahmat dan karunia-Nya penulis bisa menyelesaikan tesis yang sederhana ini dengan judul ”Perlindungan Hak Cipta Atas Motif Batik Sebagai Warisan Budaya Bangsa (Studi Terhadap Karya Seni Batik Tradisional Kraton Surakarta)”. -

(Attachment 2)“Yama, Hoko, Yatai Float Festivals”: List of 33 Important

( ) Attachment 2 “Yama, Hoko, Yatai float festivals”: List of 33 Important Intangible Folk Cultural Properties designated by the Government of Japan Name of Festival Preservation Group Prefecture City/Town The Association for the Preservation Aomori The Grand Hachinohe Sansha Festival(designated in 2004) of the Float Ceremony at the Grand Hachinohe City Prefecture Hachinohe Sansha Festival The Association for the Preservation of the Kakunodate Festival The Float Festival of Kakunodate(designated in 1991) Senboku City The Association for Tsuchizaki Akita The Tsuchizaki Shimmei Shrine Festival(designated in 1997) Akita City Shimmei Shrine Prefecture The Hanawa Festival(designated in 2014) Kazuno City Committee for the Hanawa-bayashi Festival The Association for the Preservation Yamagata The Shinjo Festival (designated in 2009) of the Float Ceremony at the Shinjo Shinjo City Prefecture Festival The Association for the Preservation Ibaraki Hitachi Furyumono(designated in 1977) Hitachi City of Hitachi Hometown Performing Arts Prefecture The Association for the Preservation Karasuyama Yamaage(designated in 1979) Nasu Karasuyama of the Karasuyama Yamaage Tochigi City The Association for the Preservation Prefecture The Kanuma Imamiya Shrine Festival(designated in 2003) Kanuma City of the Kanuma Imamiya Float Festival The Committee for the Preservation of the Chichibu Festival The Chichibu Festival(designated in 1979) Saitama Chichibu City The Association for the Preservation The Kawagoe Hikawa Festival(designated in 2005) Prefecture Kawagoe City -

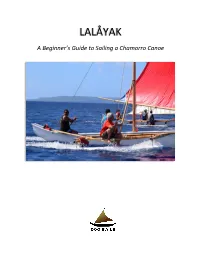

Lalåyak – a Beginner's Guide to Sailing a Chamorro Canoe

LALÅYAK A Beginner’s Guide to Sailing a Chamorro Canoe © 2019 500 Sails. All rights reserved. This project was made possible by support from the Northern Marianas Humanities Council, a non-profit, private corporation funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities. The Northern Marianas Humanities Council will have non-exclusive, nontransferable, irrevocable, royalty-free license to exercise all the exclusive rights provided by copyright. Cover photo: Jack Doyle Pictured left to right: Cecilio Raiukiulipiy, Ivan Ilmova, Pete Perez (close canoe); Sophia Perez, Arthur De Oro, Vickson Yalisman (far canoe) Sail between Saipan and Tinian in Tinian Channel. Aguiguan Island in background. Table of Contents Preface .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 2 Historic Context ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Sakman Design .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Sailing Vocabulary ........................................................................................................................................ -

Flood Loss Model Model

GIROJ FloodGIROJ Loss Flood Loss Model Model General Insurance Rating Organization of Japan 2 Overview of Our Flood Loss Model GIROJ flood loss model includes three sub-models. Floods Modelling Estimate the loss using a flood simulation for calculating Riverine flooding*1 flooded areas and flood levels Less frequent (River Flood Engineering Model) and large- scale disasters Estimate the loss using a storm surge flood simulation for Storm surge*2 calculating flooded areas and flood levels (Storm Surge Flood Engineering Model) Estimate the loss using a statistical method for estimating the Ordinarily Other precipitation probability distribution of the number of affected buildings and occurring disasters related events loss ratio (Statistical Flood Model) *1 Floods that occur when water overflows a river bank or a river bank is breached. *2 Floods that occur when water overflows a bank or a bank is breached due to an approaching typhoon or large low-pressure system and a resulting rise in sea level in coastal region. 3 Overview of River Flood Engineering Model 1. Estimate Flooded Areas and Flood Levels Set rainfall data Flood simulation Calculate flooded areas and flood levels 2. Estimate Losses Calculate the loss ratio for each district per town Estimate losses 4 River Flood Engineering Model: Estimate targets Estimate targets are 109 Class A rivers. 【Hokkaido region】 Teshio River, Shokotsu River, Yubetsu River, Tokoro River, 【Hokuriku region】 Abashiri River, Rumoi River, Arakawa River, Agano River, Ishikari River, Shiribetsu River, Shinano -

Alternative 11(1)Online 01.Indd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato USING TWITTER IN AN INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE An analysis of te reo Mäori tweets Te Taka Keegan* Paora Mato† Stacey Ruru‡ Abstract Language revitalization theory suggests that one way to improve the health of a language is to increase the number of domains where the language is used. Social network platforms provide a variety of domains where indigenous-language communities are able to communicate in their own languages. Although the capability exists, is social networking being used by indigenous-language communities? This paper reports on one particular social networking platform, Twitter, by using two separate methodologies. First, Twitter statistics collated from the Indigenous Tweets website are analysed. The data show that languages such as Basque, Haitian Creole, Welsh, Irish Gaelic, Frisian and Kapampangan do have a presence in the “Twittersphere”. Further analysis for te reo Mäori (the Mäori language) shows that tweets in te reo Mäori are rising and peak when certain events occur. The second methodology involved gathering empirical data by tweeting in te reo Mäori. This served two purposes: it allowed an ancillary check on the validity of the Indigenous Tweets data and it allowed the opportunity to determine if the number of indigenous- language tweets could be infl uenced by the actions of one tweeter. * Senior Lecturer, Computer Science Department, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand. Email: [email protected] † PhD candidate, Computer Science Department, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand. ‡ Summer Internship, Computer Science Department, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Page Auē Le Oti: Samoan Death Rituals in a New Zealand Context. Abstract

Auē le oti: Samoan death rituals in a New Zealand context. Byron Malaela Sotiata Seiuli1 University of Waikato Abstract Given that dialogue relating to death and grief for many Samoans still remains in the realm of tapu (sacred) or sā (protected), few attempts have been made by researchers of Samoan heritage to understand whether the cultural contexts for enacting associated rituals might also provide avenues for healing. Psychological scholarship on recovery following death, particularly among men, is largely based on dominant western perspectives that continue to privilege both clinical and ethnocentric perspectives as the norm. This case presentation, which forms part of a larger doctoral research by the author, demonstrates that some Samoan end-of-life rituals opens space for greater consideration of recovery from death as a culturally-defined process. In many instances, instead of severing ties with the deceased person as is popular in clinical approaches to grief work, Samoan grief resolution strongly endorses continued connections through its mourning patterns. Their end-of-life enactment helps to transition the deceased from this life to the next, while drawing the living together. Critically, the performance and maintenance of such important tasks create space for heaving emotions to be calmed, where meaning is made, and where the lives of those impacted are slowly restored. Some of these familiar rituals offer therapeutic value, enabling Samoans involved in this study to walk hand-in-hand with their emotional distress, while