Linguistics Reconstruction: Case of Polynesian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Dimensions of Language Change

Social dimensions of language change Lev Michael 1 Introduction Language change results from the differential propagation of linguistic vari- ants distributed among the linguistic repertoires of communicatively inter- acting individuals in a given community. From this it follows that language change is socially-mediated in two important ways. First, since language change is a social-epidemiological process that takes place by propagating some aspect of communicative practice across a socially-structured network, the organization of the social group in question can affect how a variant propagates. It is known, for example, that densely connected social net- works tend to be resistant to innovations, where as more sparsely connected ones are more open to them. Second, social and cultural factors, such as lan- guage ideologies, can encourage the propagation of particular variants at the expense of others in particular contexts, likewise contributing to language change. The purpose of this chapter is to survey our current understanding of the social factors that affect the emergence and propagation of linguistic variants, and thus language change, by bringing together insights from vari- ationist sociolinguistics, sociohistorical linguistics, linguistic anthropology, social psychology, and evolutionary approaches to language change. It is im- portant to note that there are, as discussed in Chapter 1, important factors beyond the social ones discussed in this chapter that affect variant propaga- 1 tion and language change, including factors related to linguistic production and perception, and cognitive factors attributable to the human language faculty (see Chapter 1). 1.1 Theorizing variation and language change As Weinreich, Labov, and Herzog (1968) originally observed, theories of lan- guage that assume linguistic variation to be noise or meaningless divergence from some ideal synchronically homogeneous linguistic state { to be elim- inated by `averaging' or `abstraction' { encounter profound difficulties in accounting for language change. -

The Origin of Language and Communication

Athena and Eve — Johnson Papers lution, editors Jones, Martin and Pilbeam conceded that The origin of ‘there are no non-human languages’, and then went on to observe that ‘language is an adaptation unique to humans, and yet the nature of its uniqueness and its biological basis language and are notoriously difficult to define’ [emphasis added].3 In his book, The Symbolic Species: The Co-Evolution of Language communication and the Brain, Terrance Deacon noted: ‘In this context, then, consider the case of Brad Harrub, Bert Thompson and human language. It is one of the most distinctive Dave Miller behavioral adaptations on the planet. Languages evolved in only one species, in only one way, with- By age four, most humans have developed an ability out precedent, except in the most general sense. to communicate through oral language. By age six And the differences between languages and all other 4 or seven, most humans can comprehend, as well as natural modes of communicating are vast.’ express, written thoughts. These unique abilities of What events transpired that have allowed humans to communicating through a native language clearly speak, while animals remain silent? If we are to believe the separate humans from all animals. The obvious evolutionary teaching currently taking place in colleges and question then arises, where did we obtain this dis- universities around the world, speech evolved as a natural tinctive trait? Organic evolution has proven unable to process over time. Yet no-one is quite sure how, and there elucidate the origin of language and communication. are no known animals that are in a transition phase from Knowing how beneficial this ability is to humans, non-speaking to speaking. -

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

Sociolinguistics: Language Change Wardhaugh Chapter 8

Sociolinguistics: Language Change Wardhaugh chapter 8 (Labov’s homepage: http://www.ling.upenn.edu/~wlabov/home.html) Non-prestige dialects of English and Language Dispersion A common preconception about non-prestige dialects or colloquial forms of English is that they are unsystematic and 'lazy' forms of language, and that they either reflect or even encourage illogical thought. Over the past 4 decades many linguists have studied non-prestige and colloquial forms of English (and other languages) and arrived at the conclusion that these varieties are just as systematic as prestige varieties of English, that their 'non-standard' features are typically features found in prestige varieties of other languages, and that there is no basis for claiming that their phonology, morphology or syntax reflects 'illogical' or lazy thinking. We focus here on the dialect of English that has received the most attention: it is known variously as "Black English Vernacular" (BEV), "African American Vernacular English" (AAVE) or "Ebonics". The first two terms are the most commonly used terms used in sociolinguistic research; the third term has achieved wide recognition in the wake of a highly controversial resolution of the Oakland (CA) Board of Education involving the role of Ebonics in K-12 education. In what follows I will use the term AAVE, which is the most widespread term in current linguistic research. Some excellent readily accessible articles on AAVE are available on-line. Note1: the colloquial English spoken by African American communities spans a wide varieties of styles, often identical to or barely distinguishable from the English spoken by other ethnic groups, including the prestige white variety. -

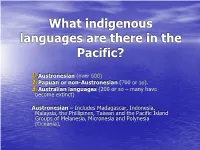

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

Language Change in Apparent and Real Time: the Community and the Individual

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 10 Issue 2 Selected Papers from NWAVE 32 Article 17 2005 Language Change in Apparent and Real Time: The Community and the Individual Natalie Schilling-Estes Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Schilling-Estes, Natalie (2005) "Language Change in Apparent and Real Time: The Community and the Individual," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 10 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol10/iss2/17 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol10/iss2/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Language Change in Apparent and Real Time: The Community and the Individual This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol10/iss2/17 Language Change in Apparent and Real Time: The Community and the Individual1 Natalie Schilling-Estes 1 Introduction Since William Labov's ( 1963) pioneering work on language variation and change in Martha's Vineyard and New York City in the 1960s, most varia tionist investigations of language change in progress have investigated change in apparent time---that is, in the speech of individuals of different generations at a given moment in time---rather than real time. This approach is based on the APPARENT TIME CONSTRUCT, which holds that, for the most part, the core features of an individual's vernacular language variety are so lidified for life by the time they reach their late teens. The robustness of the apparent time construct has been borne out in a number of studies over the past four decades (e.g. -

Language Change: Progress Or Decay?

Language change: progress or decay? Third edition JEAN AITCHISON Professor of Language and Communication, University of Oxford published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 1991, 2001 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published by Fontana Press in 1981 Second edition published by Cambridge University Press in 1991 Reprinted 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1998 Third edition 2001 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeface 10/12 pt Photina [gc] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 521 79155 3 hardback ISBN 0 521 79535 4 paperback Contents Preface page ix Part 1 Preliminaries 1 The ever-whirling wheel 3 The inevitability of change 2 Collecting up clues 19 Piecing together the evidence 3 Charting the changes 37 Studying changes in progress Part 2 Transition 4 Spreading the word 55 From person to person 5 Conflicting loyalties 68 Opposing social pressures 6 Catching on and taking off 84 How sound changes spread through a language -

The Origins and the Evolution of Language Salikoko S. Mufwene

To appear in a shortened version in The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics, ed. by Keith Allan. I’ll appreciate your comments on this one, because this project is going to grow into a bigger one. Please write to [email protected]. 6/10/2011. The Origins and the Evolution of Language Salikoko S. Mufwene University of Chicago Collegium de Lyon (2010-2011) 1. Introduction Although language evolution is perhaps more commonly used in linguistics than evolution of language, I stick in this essay to the latter term, which focuses more specifically on the phylogenetic emergence of language. The former, which has prompted some linguists such as Croft (2008) to speak of evolutionary linguistics,1 applies also to changes undergone by individual languages over the past 6,000 years of documentary history, including structural changes, language speciation, and language birth and death. There are certainly advantages, especially for uniformitarians, in using the broader term. For instance, one can argue that some of the same evolutionary mechanisms are involved in both the phylogenetic and the historical periods of evolution. These would include the assumption that natural selection driven by particular ecological pressures applies in both periods, and social norms emerge by the same 1 Interestingly, Hombert & Lenclud (in press) use the related French term linguistes évolutionnistes ‘evolutionary linguists’ with just the other rather specialized meaning, focusing on phylogenesis. French too makes a distinction between the more specific évolution du langage ‘evolution of language’ and the less specific évolution linguistique ‘linguistic/language evolution’. So, Croft’s term is just as non-specific as language evolution and évolution linguistique (used even by Saussure 1916). -

The Phonemic Reality of Polynesian Vowel Length

The Phonetic Nature of Niuean * Vowel Length Nicholas Rolle University of Toronto In this paper, I argue that in Niuean, long vowels are underlying sequences of two qualitatively identical vowels, extending an analysis laid out in Taumoefolau (2002) on the related Tongic language Tongan. She argues that a long vowel will result predictably when stress falls on the first element of a double monophthong vowel sequence. Thus vowel length in these languages is a phonetic, not phonological, phenomenon. This account for vowel length is worked into an Optimality Theory (OT) framework, which crucially constrains RH- CONTOUR and ALL-FT-RIGHT above a constraint against double articulation, DIST(INCT). In addition, I provide a review of the literature concerning vowel length across Polynesian languages, and conclude that this analysis cannot be extended to all members of the Polynesian language family. 1. Introduction Across Polynesian languages, the presence of long vowels is uncontroversial, though whether these are only surface long vowels (i.e. phonetic) or underlying long vowels (i.e. phonemic) remains a contentious topic. In this paper, I outline an analysis of Tongan long vowels laid out in Taumoefolau (2002), and later supported by Anderson & Otsuka (2006), and extend this analysis to the related Tongic language Niuean. It is argued in Taumoefolau (2002) that Tongan long vowels are underlying identical vowel-vowel sequences (/ViVi/), whose surface manifestation is predictably a long vowel if stress falls on the first vowel of this sequence, and a double articulated vowel if stress falls on the second. This analysis is laid out in detail in section 3, preceded by a section describing some basic facts of Tongan phonology, and a review of the previous analyses of Tongan vowel length. -

Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori O Te Pae Tonga O Te Kuki Airani Also Known As Southern Cook Islands Māori

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. Editors: Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori SALLY AKEVAI NICHOLAS Cite this article: Sally Akevai Nicholas (2018). Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori. In Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. London: EL Publishing. pp. 36-64 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/160 This electronic version first published: July 2018 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori Sally Akevai Nicholas School of Language & Culture, Auckland University of Technology Language Name: Southern Cook Islands Māori Language Family: East Polynesian, Polynesian, Oceanic, Austronesian ISO 639-3 Code: rar Glottolog Code: raro1241 Number of speakers: ~15,000 - 20,2001 Location: 8-23S, 156-167W Vitality rating: EGIDS between 7 (shifting) and 8a (moribund) 1. -

Syntactic and Semantic Features for Code-Switching Factored Language Models Heike Adel, Ngoc Thang Vu, Katrin Kirchhoff, Dominic Telaar, and Tanja Schultz

This is the author’s version of an article that has been published in this journal. Changes were made to this version by the publisher prior to publication. The final version of record is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TASLP.2015.2389622 IEEE/ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUDIO, SPEECH AND LANGUAGE PROCESSING 1 Syntactic and Semantic Features For Code-Switching Factored Language Models Heike Adel, Ngoc Thang Vu, Katrin Kirchhoff, Dominic Telaar, and Tanja Schultz Abstract This paper presents our latest investigations on different features for factored language models for Code-Switching speech and their effect on automatic speech recognition (ASR) performance. We focus on syntactic and semantic features which can be extracted from Code-Switching text data and integrate them into factored language models. Different possible factors, such as words, part-of-speech tags, Brown word clusters, open class words and clusters of open class word embeddings are explored. The experimental results reveal that Brown word clusters, part-of-speech tags and open-class words are the most effective at reducing the perplexity of factored language models on the Mandarin-English Code-Switching corpus SEAME. In ASR experiments, the model containing Brown word clusters and part-of-speech tags and the model also including clusters of open class word embeddings yield the best mixed error rate results. In summary, the best language model can significantly reduce the perplexity on the SEAME evaluation set by up to 10.8% relative and the mixed error rate by up to 3.4% relative. I. INTRODUCTION The term Code-Switching (CS) denotes speech with more than one language. -

Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change Grammaticalization, Refunctionalization and Beyond

Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change Grammaticalization, Refunctionalization and Beyond Edited by Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen and Mar Garachana Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Languages www.mdpi.com/journal/languages Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change Studies in Historical Linguistics and Language Change. Grammaticalization, Refunctionalization and Beyond Special Issue Editors Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen Mar Garachana MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editors Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen Mar Garachana Utrecht University Barcelona University The Netherlands Spain Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Languages (ISSN 2226-471X) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/languages/ special issues/Lingustics LanguageChange) For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-576-8 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-577-5 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Bob de Jonge. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editors ....................................