Eastern Polynesian: the Linguistic Evidence Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polynesian Case

Lexicostatistics Compared with Shared Innovations: the Polynesian Case jK=dÉääJj~ååI=fK=mÉáêçëI=pK=pí~êçëíáå Santa Fe Institute The Polynesian languages, together with Fijian and Rotuman, consti- tute the Central Oceanic branch, which is usually included in a bigger Oceanic family, part of Austronesian. The Polynesian language family consists of 28 languages ([BIGGS 98]) most of which are fairly well known. The history of the family is also well investigated: we have the phonological reconstruction of its protolan- guage ([BIGGS 98], [MARCK 2000]), suggestions about morphology and syntax ([WILSON 982]; [CLARK 96]), and a detailed comparative diction- ary of the family — probably one of the best etymological dictionaries for languages outside Eurasia ([BIGGS n.d.]) The Proto-Polynesian consonantal system is reconstructed as ([BIGGS 98: 08–09]): *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l *r *k *ŋ (*h) `*ʔ Using the principle of «irreversible changes», one can see that the systems of daughter languages could be derived from Proto-Polynesian through a sequence of simple innovations (mostly mergers): . Proto-Tongan: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *r > *k *ŋ *h *ʔ .. Tongan p m f w t n h l k ŋ ʔ 2. Proto-Nuclear Polynesian: *p *m *f *w *t *n *s *l = *r *k *ŋ *h > * GÉää-M~åå, PÉáêçë, S. Sí~êçëíáå. Lexicostatistics & Shared Innovations . 2. Samoa p m f w t n s l *k > ʔ ŋ 2.2. East Polynesian *p *m *f *w *t *n *s > *h *l *k *ŋ * 2..3. Tahitian p m f v t n h r *k > ʔ *ŋ > ʔ 2. -

Tuhinga Pdf for TPP:Layout 1

Tuhinga 21: 99–123 Copyright © Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2010) Rediscovering the collection: Cook Islands material culture in the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Grace Hutton*, Safua Akeli** and Sean Mallon*** * Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ** Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) *** Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, PO Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: Artefacts from the Cook Islands have been collected since the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) opened in 1865 as the Colonial Museum. In this article we provide a historical overview of the Cook Islands collection at Te Papa. We discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the collection, review some of the factors influencing its growth, and consider the possibilities for future collection development. This article is an output of a survey of the Cook Islands collection carried out between 2007 and 2009. KEYWORDS: Te Papa, Cook Islands collection, Pacific Cultures collection, Pacific Islanders, New Zealand, museums. Introduction to New Zealand in recent decades. What began in the It is only since 1993 that the Museum of New Zealand Te nineteenth century as a comparative collection of ethno - Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa) has managed its Pacific treasures graphic ‘specimens’ – objects collected during the scientific as a separate collection. For most of the institution’s history study of peoples and cultures – has broadened to include (as the Colonial Museum from 1865 to 1907, the Dominion contemporary works by known artists. -

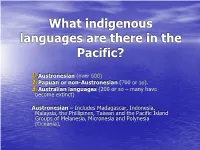

What Languages Are There in the Pacific?

What indigenous languages are there in the Pacific? 1.Austronesian (over 600) 2.Papuan or non-Austronesian (700 or so). 3.Australian languages (200 or so – many have become extinct) Austronesian – Includes Madagascar, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Phillipines, Taiwan and the Pacific Island Groups of Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia (Oceania). Austronesia’s four branches: 1. Western (Non-Oceanic) (about 388 languages, including Malagasy (Madagascar), most of the languages of Indonesia and Malaysia, all Phillipines, the Chamic languages of Vietnam, Palauan (spoken in the western Carolines) and Chamorro (spoken in the Mariana Islands) in Western Micronesia. About 178 million speakers. 2. & 3. Also two smaller branches in Eastern Indonesia and the aboriginal languages of Taiwan. Place of Polynesia 4. Oceanic or Eastern Branch - Includes Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. 2.1 million speakers, 382 languages. Divided into 20+ local groups. Central Pacific Group consists of Polynesian, Fijian, Rotuman. Remaining groups include the languages of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, the Solomons, many languages of coastal New Guinea and its offshore islands, and most of Micronesia. Brief history of the Polynesian languages • Round about 6,000 years ago, the ancestors of the Polynesians - a people we now call Austronesians - moved from South-East Asia, through Melanesia - Papua New Guinea, Solomons, Vanuatu (New Hebrides), to Fiji. • We don't know what these ancestors looked like at that time - probably like Asians with straight black hair, fair skin and oriental eyes. Western Polynesia Once in Fiji, about 3,500 years ago, these people stepped off to the first Polynesian islands - Tonga, Samoa, Niue, and surrounding islands like `Uvea, Futuna, Tokelau, and Tuvalu. -

Roger Curtis Green March 15, 1932–October 4, 2009

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ROGE R C U R T I S Gr EEN 1 9 3 2 — 2 0 0 9 A Biographical Memoir by PAT R I C K V . K I R CH Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 2010 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON, D.C. ROGER CURTIS GrEEN March 15, 1932–October 4, 2009 BY P ATRICK V . KIRCH OGER CURTIS GREEN, A TOWERING FIGURE in Pacific anthro- Rpology, passed away in his beloved home in Titirangi nestled in the hills overlooking Auckland on October 4, 2009, at the age of 77 years. Roger was one of the most influential archaeologists and historical anthropologists of Oceania in the second half of the 20th century. He revolutionized the field of Polynesian archaeology through his application of the settlement pattern approach. He conducted significant field research in New Zealand, French Polynesia, Samoa, Hawai‘i, the Solomon Islands, and the Bismarck Archipelago, advancing our knowledge of prehistory across the Pacific. His collaborations with historical linguists provided a firm foundation for the use of language reconstructions in prehis- tory, and he helped to advance a phylogenetic approach to historical anthropology. The Lapita Cultural Complex, now widely appreciated as representing the initial human settle- ment of Remote Oceania, was first largely defined through his efforts. And, he leaves an enduring legacy in the many students he mentored. EARLY YEARS Roger’s parents, Eleanor Richards (b. 1908) and Robert Jefferson Green (b. -

Bird-Man Amulets and Tridacna Shell Discs from Taumako, Solomon Islands

478 Susan Bulmer JONES, K.L., 1981. New Zealand Mataa from Marlborough, Nelson, and the Chatham Islands.New Zealand Journal of Archaeology, 3:89-107. KLEIN, J., J.C. LERMAN, D.E. DAMON, and E.K. RALPH, 1982. Calibration of Radiocarbon Dates.Radiocarbon, 24(2): 193-50. LEACH, H.M., 1981. Technological Changes in the Development of Polynesian Adzes, in F. Leach and J. Davidson (eds), Archaeological Studies of Pacific Stone Resources. B.A.R. International Series 104. Oxford, B.A.R. pp.167-82. MAJNEP, I.S., and R. BULMER, 1977. Birds of My Kalam Country. Auckland, Auckland University Press. McCOY, P.C., 1979. Easter Island, in J.D. Jennings (ed.), The Prehistory of Polynesia, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, pp. 135-66. MOUNTAIN, Mary-Jane, 1983. Preliminary Report of Excavations at Nombe Rockshelter, Simbu Province.Indo- Paciftc Prehistory Association Newsletter, 4:84-99. NASH, J., and D.D. MITCHELL, 1973. A Note on Some Chipped Stone Objects from South Bougainville.Journal of the Polynesian Society, 82(2):209-12. PAWLEY, A., and R.C. GREEN, 1984. The Proto-Oceanic Language Community.Journal of Pacific History, 19:123- 46. STUIVER, M., and B. BECKER, 1986. High Precision Decadel Calibration of the Radiocarbon Time Scale, AD 1950- 2500 BC. Radiocarbon, 23(28):863-910. SWADLING, P., 1984. Sepik Prehistory. Paper presented to Wenner Gren Symposium, Sepik Research Today: The Study of Sepik Cultures in and for Modem Papua New Guinea, Basel, Switzerland. SWADLING, P., J. CHAPPELL, G. FRANCIS, N. ARAHO, and B. IVUYO, 1989. A Late Quaternary Inland Sea and Early Pottery in Papua New Guinea.Archaeology in Oceania, 24(3): 106-9. -

The Phonemic Reality of Polynesian Vowel Length

The Phonetic Nature of Niuean * Vowel Length Nicholas Rolle University of Toronto In this paper, I argue that in Niuean, long vowels are underlying sequences of two qualitatively identical vowels, extending an analysis laid out in Taumoefolau (2002) on the related Tongic language Tongan. She argues that a long vowel will result predictably when stress falls on the first element of a double monophthong vowel sequence. Thus vowel length in these languages is a phonetic, not phonological, phenomenon. This account for vowel length is worked into an Optimality Theory (OT) framework, which crucially constrains RH- CONTOUR and ALL-FT-RIGHT above a constraint against double articulation, DIST(INCT). In addition, I provide a review of the literature concerning vowel length across Polynesian languages, and conclude that this analysis cannot be extended to all members of the Polynesian language family. 1. Introduction Across Polynesian languages, the presence of long vowels is uncontroversial, though whether these are only surface long vowels (i.e. phonetic) or underlying long vowels (i.e. phonemic) remains a contentious topic. In this paper, I outline an analysis of Tongan long vowels laid out in Taumoefolau (2002), and later supported by Anderson & Otsuka (2006), and extend this analysis to the related Tongic language Niuean. It is argued in Taumoefolau (2002) that Tongan long vowels are underlying identical vowel-vowel sequences (/ViVi/), whose surface manifestation is predictably a long vowel if stress falls on the first vowel of this sequence, and a double articulated vowel if stress falls on the second. This analysis is laid out in detail in section 3, preceded by a section describing some basic facts of Tongan phonology, and a review of the previous analyses of Tongan vowel length. -

Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori O Te Pae Tonga O Te Kuki Airani Also Known As Southern Cook Islands Māori

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. Editors: Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori SALLY AKEVAI NICHOLAS Cite this article: Sally Akevai Nicholas (2018). Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori. In Peter K. Austin & Lauren Gawne (eds) Language Documentation and Description, vol 15. London: EL Publishing. pp. 36-64 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/160 This electronic version first published: July 2018 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language Contexts: Te Reo Māori o te Pae Tonga o te Kuki Airani also known as Southern Cook Islands Māori Sally Akevai Nicholas School of Language & Culture, Auckland University of Technology Language Name: Southern Cook Islands Māori Language Family: East Polynesian, Polynesian, Oceanic, Austronesian ISO 639-3 Code: rar Glottolog Code: raro1241 Number of speakers: ~15,000 - 20,2001 Location: 8-23S, 156-167W Vitality rating: EGIDS between 7 (shifting) and 8a (moribund) 1. -

Stone Tools from the Ancient Tongan State Reveal Prehistoric Interaction Centers in the Central Pacific

Stone tools from the ancient Tongan state reveal prehistoric interaction centers in the Central Pacific Geoffrey R. Clarka,1, Christian Reepmeyera, Nivaleti Melekiolab, Jon Woodheadc, William R. Dickinsond, and Helene Martinsson-Walline aArchaeology and Natural History, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia; bLapaha Town Council, Lapaha Village, Tongatapu, Kingdom of Tonga; cSchool of Earth Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Australia; dDepartment of Geoscience, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721; and eDepartment of Archaeology and Ancient History, Gotland Campus, Uppsala University, 75105 Uppsala, Sweden Edited by Patrick V. Kirch, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved June 10, 2014 (received for review April 2, 2014) Tonga was unique in the prehistoric Pacific for developing a mari- involved control and distribution of prestige exotic goods by elites time state that integrated the archipelago under a centralized and whether the polity’s interaction sphere was only one of several authority and for undertaking long-distance economic and political prehistoric networks responsible for the movement of people, exchanges in the second millennium A.D. To establish the extent goods, and ideas in the Central Pacific. of Tonga’s maritime polity, we geochemically analyzed stone tools This article reports the analysis of a significant lithic artifact excavated from the central places of the ruling paramounts, par- assemblage recovered during recent excavations of sites of the ticularly lithic artifacts associated with stone-faced chiefly tombs. Tongan polity, which was manifested by the construction of The lithic networks of the Tongan state focused on Samoa and Fiji, religo-political centers containing monumental architecture on with one adze sourced to the Society Islands 2,500 km from Ton- the island of Tongatapu (297 km2), where the political hier- gatapu. -

Making a Case for Tongan As an Endangered Language

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Making a Case for Tongan as an provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa Endangered Language Yuko Otsuka At fi rst glance, Tongan appears far from being endangered. It has nearly 100,000 speakers—remarkably sizable compared to other languages of Oceania—and is spoken in a predominantly monolingual and monocul- tural society.1 Furthermore, Tonga is an independent nation-state, in fact, the last kingdom in Polynesia. Why should one be talking at all about Tongan being endangered? This paper examines the linguistic situation in Tonga and argues that there are reasons to be concerned about the future of the Tongan language in the long run. The position put forward in this paper is as follows: In the postcolonial context, many instances of language endangerment should be defi ned in terms of a unit larger than a nation-state. Globalization has put small island nations like Tonga in a position such that, in order to survive, they are compelled to conform to the Western development model that is asso- ciated with English as a socioeconomically privileged language. Here, the term “globalization” refers to a particular aspect of the phenomenon, that is, interconnectedness facilitated by the expansion of Euro-American values. Interconnectedness certainly has benefi cial consequences, such as bringing new opportunities. Epeli Hau‘ofa, for example, has argued that it has empowered the peoples of Oceania, liberating them from the artifi cial boundaries imposed by nineteenth-century imperialism (1993, 10). The following discussion, however, focuses on the adverse effects of intercon- nectedness, especially as it affects language maintenance. -

A Prehistoric, Noncultural Vertebrate Assemblage from Tutuila, American Samoa1

A Prehistoric, Noncultural Vertebrate Assemblage from Tutuila, American Samoa1 David W Steadman2,3 and Gregory K. Pregill4 Abstract: Ana Pe'ape'a is a small cave on the southern shore ofTutuila, Amer ican Samoa. Excavations at Ana Pe'ape'a yielded 13,600+ bones of small verte brates, dominated (>95%) by the nonnative Pacific Rat, Rattus exulans. Represented in the owl-derived bone deposit are two species that no longer oc cur on Tutuila, the Pacific Boa (Candoia bibroni) and the Sooty Crake (Porzana tabuensis). Based on bone counts, C. bibroni was the second most common species at the site. The third most common, the Sheath-tailed Bat (Emballonura semi caudata), is extremely rare on Tutuila today. Compared with bone records in nearby Tonga, we believe that the deposit at Ana Pe'ape'a, with a radiocarbon date of A.D. 445 to 640, is at least 1,000 yr too young to be dominated by extinct species. THE WEST POLYNESIAN faunal region com and Turner 1985]). Independent (formerly prises Fiji, Tonga, Samoa, and the outlying Western) Samoa comprises the very large is islands of Rotuma, 'Uvea, Futuna, 'Alofi, and lands of Upolu and Savai'i and their small Niue (Steadman 1993a, Steadman et al. offshore islands. American Samoa comprises 2000). Raised limestone islands in Fiji, Ton Tutuila, its offshore island of Aunu'u, the ga, and Niue have yielded rich deposits of Manu'a group (Ta'u, Ofu, Olosega), and the prehistoric bones in caves and rockshelters outlying atolls of Swains and Rose. that represent many extinct species or pop The wet volcanic soils of Samoa are well ulations of lizards, birds, and bats (Pregill suited for sustaining forests (Whistler 1980, 1993, Koopman and Steadman 1995, Pregill 1992, Elmqvist et al. -

Terra Australis 26

terra australis 26 Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and island Melanesia — lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: Coastal Sites in Southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: Ol Tumbuna: Archaeological Excavations in the Eastern Central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: The Geography and Ecology of Traffic in the Interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. B. Egloff (1979) Volume 5: The Great Kartan Mystery. R. Lampert (1981) Volume 6: Early Man in North Queensland: Art and Archaeology in the Laura Area. A. Rosenfeld, D. Horton and J. Winter (1981) Volume 7: The Alligator Rivers: Prehistory and Ecology in Western Arnhem Land. -

The Language of Rapa Iti: Description of a Language in Change

THE LANGUAGE OF RAPA ITI: DESCRIPTION OF A LANGUAGE IN CHANGE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2015 By Mary E. Walworth Dissertation Committee: Yuko Otsuka, Chairperson Robert Blust Katie Drager Ken Rehg Terry Hunt Keywords: Rapa Iti, Polynesia, language change, language contact Dedicated to my god-daughter, Pākora, and to all of the other young people of Rapa Iti. You all are the reason I have done this project and I hope it serves you well. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS What an adventure this dissertation has been - linguistically, professionally, and personally. This path began for me five years ago, when, somewhat randomly, I chose to study a language spoken in the most faraway place I could find in French Polynesia. I now know that this choice was not random at all, but a critical decision for my life. My friend Tākura once told me as we were looking out over Ahurei Bay one afternoon in Rapa, “there are many secrets here for you, I can't tell them to you, but I hope you will tell me when you find them out.” She was right - the secrets of language and of life that were revealed to me in Rapa are invaluable. They have changed me and my perceptions of the world. I am not the same researcher nor am I the same person that I was when I first arrived there. I met friends for life on that island, and my partner for life there.