Sussex Liberia Evaluation 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 World Englishes and their dialect roots Schreier, Daniel Abstract: This chapter investigates the persistence and development of so-called dialect roots, that is, features of local forms of British English that are transplanted to overseas territories. It discusses dialect input and the survival of features, independent developments within overseas communities, including realignments of features in the dialect inputs, as well as contact phenomena when English speakers interact with those of other dialects and languages. The diagnostic value of these roots is exemplified with selected cases from around the world (Newfoundland English, Liberian English, Caribbean Englishes), which are assessed with reference to the archaic/dynamic character of individual features in new-dialect formation and language-contact scenarios. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-198161 Book Section Published Version The following work is licensed under a Publisher License. Originally published at: Schreier, Daniel (2020). World Englishes and their dialect roots. In: Schreier, Daniel; Hundt, Marianne; Schneider, Edgar W. The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 384-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots Daniel Schreier World Englishes developed out of English dialects spoken throughout the British Isles. These were transported all over the globe by speakers from different regions, social classes, and educational backgrounds, who migrated with distinct trajectories, for various periods of time and in distinct chronolo- gical phases (Hickey, Chapter 2, this volume; Britain, Chapter 7,thisvolume). -

Attitudes Towards English in Ghana Kari Dako

Dako & Quarcoo / Legon Journal of the Humanities (2017) 20-30 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v28i1.3 Attitudes towards English in Ghana Kari Dako Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana [email protected]; [email protected] Millicent Akosua Quarcoo Senior Lecturer, Department of English Education, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana [email protected]; [email protected] Submitted: May 16, 2014 /Accepted: September 4, 2014 / Published: May 31, 2017 Abstract The paper considers official and individual attitudes towards bilingualism in English and a Ghanaian language. We ask whether bilingualism in English and Ghanaian languages is a social handicap, without merit, or an important indicator of ethnic identity. Ghana has about 50 non-mutually intelligible languages, yet there are no statistics on who speaks what language(s) where in the country. We consider attitudes to English against the current Ghanaian language policy in education as practised in the school system. Our data reveal that parents believe early exposure to English enhances academic performance; English is therefore becoming the language of the home. Keywords: attitudes, English, ethnicity, Ghanaian languages, language policy Introduction Asanturofie anomaa, wofa no a, woafa mmusuo, wogyae no a, wagyae siadeé. (If you catch the beautiful nightjar, you inflict on yourself a curse, but if you let it go, you have lost something of great value). The attitude of Ghanaians to English is echoed in the paradox of this well-known Akan proverb. English might be a curse but it is at the same time a valuable necessity. Attitudes are learned, and Garret (2010) reminds us that associated with attitudes are ‘habits, values, beliefs, opinions as well as social stereotypes and ideologies’ (p.31). -

From the Sidelines to the Forefront Ensuring a Gender-Responsive Foundation for Liberia’S National Decentralization Process

From the Sidelines to the Forefront Ensuring a Gender-Responsive Foundation for Liberia’s National Decentralization Process: A Review and Analysis of Barriers, Opportunities and Entry Points A Study by the Governance Commission and Ministry of Gender and Development and UN Women February 2014 DEDICATION This study is dedicated to Sheelagh Kathy Mangones, UN Women Representative to Liberia, who sadly passed away on 4th February 2014 while attending an Africa regional meeting in Addis Ababa. Ms. Mangones was a humanitarian, dedicated to promoting the cause of women’s empowerment world-wide. Passionate about women’s participation at all levels, Kathy was committed to ensuring that Liberia’s decentralization opens new opportunities for Liberia’s rural women. This tribute is in recognition of her relentless efforts in promoting women’s empowerment and participation during her time in Liberia. She will be missed. Page 2 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................................ 5 FOREWORDS ............................................................................................................................... 7 PREFACE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 9 DEFINITION OF KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS ................................................................................ 10 SECTION I: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ -

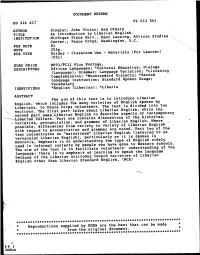

An Introduction to Liberian English

DOCUMENT RESUME FL 013 561 ED 226 617 AUTHOR Singler, John Victor; AndOthers An Introduction toLiberian English. TITLE Lansing. African Studies INSTITUTION Michigan State Univ.', East Center.; Peace Corps,Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 81 , NOTE 253p. 1 PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use -Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. Education; Dialogs DESCRIPTORS African Languages; *Cultural (Language); Grammar; LanguageVariation; *Listening Comprehension; *NonstandardDialects; *Second Language,Instruction; Standard SpokenUsage; Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *English (Liberian); *Liberia ABSTRACT The aim of this text is tointroduce Liberian English, which includes the manyvarieties of English spoken by Liberians, to Peace Corps volunteers.The text is dividedinto two sections. The first part talksabout Liberian English,while the sedond part uses LiberianEnglish to describe aspectsof contemporary --------Li-berfairdiature. Part one containsdiscussions of the histories, varieties, pronunciation, and grammarof Liberian English. Where possible, differences fromvariety to variety of LiberianEnglish and grammar are noted.1Parttwo of the with regard to pronunciation i(referred to as text concentrates on"mainstream" Liberian English vernacular Liberian English),particularly as it is spokenin Monrovia. Emphasis is onunderstanding the type of Englishwidely by people who have gone toWestern schools. used in informal contexts understanding of the The aim of the text is tofacilitate volunteers' language; there is no emphasison learning to speak the language because of the Liberianattitudes toward varieties ofLiberian English other than LiberianStandard English. (NCR) **********************************************************.************* the best that can be made * * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are * * from the original document. *********************************************************************** is Jr) VC) C\I CD 1.1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO LIBERIAN ENGLISH BY JOHN VICTOR S I NGLER wi th J. -

Lntroduction

BerndKortmann and Kerstin Lunkenheimer lntroduction 1 Backgroundand history of this atlas This atlas offers a large-scaletypological survey of morphoslmtactic variation in the Anglophone world, basedon the analysisof 3OLl and 18indigenized L2varieties of English as well 25 English-basedpidgins and creolesfrom eight different world regions (Africa, Australia, the British Isles, the Caribbean,North America, the Pacific, South and SoutheastAsia and, as the borderline caseof an Anglophone world region, the South Atlantic). It is the outgrowth of a major electronic databaseand open accessresearch tool edited by the present editors in 2Oll (The electronicWord Atlas of Varietiesof English,short: eWAVEThttp://www.ewave- atlas.org/) and is a direct, but far more comprehensivefollow-up of the interactive CD-ROMaccompanying the Mouton de GruyterHandbook of Varietiesof English(Kortmann et al. 2oo4), Whereasthe grammar part of the latter survey was based on 75 morphoslmtacticfeatures in 46 varieties of English and English-based pidgins and creoles worldwide, its successor,the WAVEdatabase (WAVE short for: World Atlas of Vaiation in English),holds information on 235morphosyntactic features in74 datasets, i.e. about five times as much de- tail and information. The idea underlying the design of WAVEwas to createa considerablylarger and more @ fine-graineddatabase and researchtool than back in 20O4,especially one that is less Ll-centred. As a proper atlas should, WAVEis intended to survey and map the morphosyntacticvariation spacein the Anglophone world and to help us explore how much of this variation spaceis made use of in different (clustersof) varieties of English, and to what extent it is possibleto correlatethe structural profiles for indi- vidual and goups of varietieswith, for example, geography,socio-history or generalprocesses of language change,language acquisition and languagecontact. -

Storytelling Traditions of Philadelphia's Liberian Elders

From West Africa to West Philadelphia Storytelling Traditions of Philadelphia’s Liberian Elders A Collaborative Project of The Center for Folklore and Ethnography University of Pennsylvania and The Agape African Senior Citizens Center 229 North 63rd Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Table of Contents Preface ....................................................................................................2 Liberia and the Philadelphia Community ........................................................5 Liberian Languages and Community Storytelling .............................................8 The Stories ...............................................................................................10 How Monkey Tricked Alligator by Edith Hill ....................................................10 Three Truths that Deer Told Leopard by John K. Jallah ..................................... 11 How the Animals Became Different Colors by Benjamin Kpangbah .......................12 Why Elephant is Afraid of Goat by Deddeh Passawee ........................................14 Greedy Spider by Ansumana Passawee .........................................................15 Which Brother Should Marry the King’s Daughter? by Ansumana Passawee ............16 Hawk and Hen by Edith Hill ........................................................................18 Which Wife Should Die? by Peter Sirleaf ........................................................19 Why Rabbit Sleeps When Leopard Chases Him by Deddeh Passawee .....................20 Leopard and -

The Phonology and Morphology of Kisi

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title The Phonology and Morphology of Kisi Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7b3788dp Author Childs, George Publication Date 1988 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Phonology and Morphology of Kisi By George Tucker Childs A.B. (Stanford University) 1970 M.Ed. (University of Virginia) 1979 M.A. (University of California) 1982 C.Phil. (University of California) 1987 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LINGUISTICS in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Chairman Date r, DOCTORAL DEGREE CONFERRED MAT 20,1980 , Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE PHONOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGY OF KISI Copyright (£) 1988 All rights reserved. George Tucker Childs Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE PHONOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGY OF KISI George Tucker Childs ABSTRACT This dissertation describes the phonology and morphology of the Kisi language, a member of the Southern Branch of (West) Atlantic. The language is spoken in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia. After the introduction in Chapter 1 and an overview of the language in Chapter 2, I discuss the phonology of the language. The phonemic inventory has implosives, a full series of nasal compound stops, and a set of labialvelars. The vowels form a symmetrical seven- vowel pattern, and length is contrastive. Syllable structure is , C(G)V(V)(C), where the only consonants allowed to close syllables are the liquid and two nasals. Kisi is a tonal language with the following tones: Low, High, Extra-High (limited distribution), Rise, and Fall. -

'She Bes Delighted with Herself' – Habitual Marking in Irish English

0 Södertörns högskola | Institutionen för kultur och lärande Kandidatuppsats 15 hp | Engelska | vårterminen 2014 ’she bes delighted with herself’ – Habitual marking in Irish English Av: Hugh Curtis Handledare: Harriet Sharp Hugh Curti 2014-06-17 1 Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND AIMS.......................................................................................................3 2.0 BACKGROUND........................................................................................................................................4 2.1 Aspect and Tense...................................................................................................................................4 2.2 Difference between continuous and progressive aspects and the simple form ...................8 2.3 Habitual aspect in Standard English ................................................................................................9 2.4 Habitual aspect in Irish English .....................................................................................................11 2.5 Historical background of the habitual markers in IrE..............................................................12 3.0 MATERIAL AND METHODS..........................................................................................................17 3.1 The Electronic World Atlas for Varieties of English...............................................................18 3.2 WebCorp Linguist's Search Engine ..............................................................................................18 -

Main Languages Other Than English Spoken in the Home (Excluding Indigenous Languages)

Main languages other than English spoken in the home (excluding Indigenous languages) In order of most common to least commonly spoken language 1. Arabic 42. Telugu 2. Vietnamese 43. Dutch 3. Mandarin 44. Polish 4. Hindi 45. Nepali 5. Greek 46. Malay 6. Cantonese 47. Bosnian 7. Spanish 48. Burmese 8. Tagalog 49. Hebrew 9. Italian 50. Albanian 10. Korean 51. Swahili 11. Samoan 52. Fijian 12. Japanese 53. Karen 13. Urdu 54. Romanian 14. Turkish 55. Pashto 15. Indonesian 56. Marathi 16. French 57. Swedish 17. Punjabi 58. Shona 18. Tamil 59. Chaldean Neo-Aramaic 19. Dari 60. Amharic 20. Sinhalese 61. Unknown 21. Bengali 62. Maori (Cook Island) 22. Malayalam 63. Hungarian 23. German 64. Kurdish 24. Russian 65. Lao 25. Serbian 66. Kannada 26. Chinese, nec 67. Hakka 27. Macedonian 68. Maltese 28. Filipino 69. Tigrinya 29. Khmer 70. Other Southeast Asian Languages 30. Afrikaans 71. Armenian 31. Thai 72. Czech 32. Tongan 73. Nuer 33. Somali 74. Hmong 34. Assyrian Neo-Aramaic 75. Danish 35. African Languages 76. Finnish 36. Gujarati 77. Slovak 37. Dinka 78. Papua New Guinea Languages 38. Croatian 79. Auslan 39. Persian (excluding Dari) 80. Kirundi (Rundi) 40. Portuguese 81. Other Eastern Asian Languages 41. Maori (New Zealand) 82. Pacific Austronesian Languages AEDI National Report 2012 1 83. Norwegian 125. Rohingya 84. Krio 126. Liberian (Liberian English) 85. Other Southern Asian Languages 127. Igbo 86. Hazaraghi 128. Estonian 87. Tai 129. Fijian Hindustani 88. Oceanian Pidgins and Creoles 130. Irish 89. Iranic 131. Invented Languages 90. Oromo 132. Lithuanian 91. Chin Haka 133. -

Some Terms from Liberian Speech

Cornell University ILR School DigitalCommons@ILR Faculty Publications - Labor Relations, Law, and History Labor Relations, Law, and History 1-1-1979 Some Terms From Liberian Speech Michael Evan Gold Cornell University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cbpubs Part of the Linguistic Anthropology Commons Thank you for downloading an article from DigitalCommons@ILR. Support this valuable resource today! This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Labor Relations, Law, and History at DigitalCommons@ILR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Labor Relations, Law, and History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@ILR. For more information, please contact catherwood- [email protected]. If you have a disability and are having trouble accessing information on this website or need materials in an alternate format, contact [email protected] for assistance. Some Terms From Liberian Speech Abstract Written by Warren L. d’Azevedo as revised and enlarged by Michael Evan Gold. Disciplines Linguistic Anthropology Comments http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cbpubs/10/ This article is available at DigitalCommons@ILR: https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cbpubs/10 . '? / / v. ' / ~. ,_:)t/1<.t C Ct~ G,A';Z. .'-L l,~O;;:70/S:'-- , ,i ~.~~~~iJ fJ£ 0 3 c./'I Z- Some Terms From Liberian Speech Lr 0&'7 by /q7i Warren L. d'Azevedo As Revised and Englarged by Michael Evan Gold 1979 Professor d'Azevedo's Introduction Like many rapidly changing countries in the world, Liberia's unique history and complex society has created a culture of great variety and richness. -

Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2013 Whiteness in Africa: Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race Robert P. Murray University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Murray, Robert P., "Whiteness in Africa: Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--History. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/23 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work. -

Language Group Specific Informational Report: Bassa

Rhode Island College M.Ed. In TESL Program Language Group Specific Informational Reports Produced by Graduate Students in the M.Ed. In TESL Program In the Feinstein School of Education and Human Development Language Group: Bassa Author: Sara Shaffer Program Contact Person: Nancy Cloud ([email protected]) Language Group Specific Informational Report: Bassa Sarah Shaffer TESL 539 Spring 2011 Language History Bassa is an Anglophone language belonging to the Niger-Congo family that has existed since around 500B.C. (Swan, 2001). It is spoken in Liberia by over 350,000 and Sierra Leone by about 7,000 people. Bassa is the second largest indigenous language spoken in Liberia. There are three regional dialects of this language. If not careful, one can confuse Bassa with other languages found in other parts of Africa, such as Basa (Nigeria) and Basaa (Cameroon) (Horace, 2010). (no author, www.worldatlas.com, 2011) Bassa- Vah Script The Bassa Vah script was originally created by a Bassa man, Dee Wahdayn. Legend says that he would write words on leaves with his teeth, instead of his hand. The words were thrown from his mouth to the leaf, hence the word “Vah”, which means “to throw a word” (Early, 2011). The script was brought to the Western world in an attempt to revive the language around 1920 by Dr. Thomas Narvan Lewis, a Bassa physician (Horace, 2010). Currently, Bassa is considered to be a dying language due to the fact that most people can speak it, but the only ones who can write in it are elder men. The Bassa language is a tonal language, meaning words with the same pronunciation but spoken in different pitches are considered to be different words altogether.