A Comparative Study of Liberian and the Gambian Varieties of West African English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter No. 57 Spring Term 2006

The Mount Malt Hill Egham Surrey TW20 9PB Email [email protected] Website www.rrf.org.uk Newsletter no. 57 Spring term 2006 Contents Editorial Jennifer Chew 3 A Story from Japan Peter Warner 4 Australian Inquiry into the Teaching of Reading Jennifer Chew 4 Jolly Phonics in The Gambia, Part Two Marj Hitching 6 You Can t Fool All Mona McNee 8 Comments from the National Union of Teachers on Jim Rose s Interim Report 11 Sound Foundations: The Intensive Synthetic-Phonics Pro- gramme for the Slowest Readers Tom Burkard 12 The Brightest Kids Need Help Too Sally R 15 Letterland: A Response to the Article in Newsletter 56 Elizabeth Nonweiler 17 Phonics: The Holy Grail of Reading? Jennifer Chew 22 Marilyn Jager Adams on The Three-Cueing System Geraldine Carter 26 Any opinions expressed in this newsletter are those of individual contributors. Copyright remains with the contributors unless otherwise stated. The editor reserves the right to amend copy. Reading Reform Foundation Committee Members Geraldine Carter Debbie Hepplewhite Lesley Charlton David Hyams (Chairman) Jennifer Chew OBE Sue Lloyd Jim Curran Prof. Diane McGuinness Maggie Downie Ruth Miskin Lesley Drake Fiona Nevola Susan Godsland Elizabeth Nonweiler Advisers: Dr Bonnie Macmillan Daphne Vivian-Neal RRF Governing Statement The Reading Reform Foundation is a non-profit-making organisation. It was founded by educators and researchers who were concerned about the high functional illiteracy rates among children and adults in the United Kingdom and in the English-speaking world. On the basis of a wealth of scientific evidence, members of the Reading Reform Foundation are convinced that most reading failure is caused by faulty instructional methods. -

17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 World Englishes and their dialect roots Schreier, Daniel Abstract: This chapter investigates the persistence and development of so-called dialect roots, that is, features of local forms of British English that are transplanted to overseas territories. It discusses dialect input and the survival of features, independent developments within overseas communities, including realignments of features in the dialect inputs, as well as contact phenomena when English speakers interact with those of other dialects and languages. The diagnostic value of these roots is exemplified with selected cases from around the world (Newfoundland English, Liberian English, Caribbean Englishes), which are assessed with reference to the archaic/dynamic character of individual features in new-dialect formation and language-contact scenarios. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-198161 Book Section Published Version The following work is licensed under a Publisher License. Originally published at: Schreier, Daniel (2020). World Englishes and their dialect roots. In: Schreier, Daniel; Hundt, Marianne; Schneider, Edgar W. The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 384-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots Daniel Schreier World Englishes developed out of English dialects spoken throughout the British Isles. These were transported all over the globe by speakers from different regions, social classes, and educational backgrounds, who migrated with distinct trajectories, for various periods of time and in distinct chronolo- gical phases (Hickey, Chapter 2, this volume; Britain, Chapter 7,thisvolume). -

Attitudes Towards English in Ghana Kari Dako

Dako & Quarcoo / Legon Journal of the Humanities (2017) 20-30 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ljh.v28i1.3 Attitudes towards English in Ghana Kari Dako Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Ghana, Legon, Ghana [email protected]; [email protected] Millicent Akosua Quarcoo Senior Lecturer, Department of English Education, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana [email protected]; [email protected] Submitted: May 16, 2014 /Accepted: September 4, 2014 / Published: May 31, 2017 Abstract The paper considers official and individual attitudes towards bilingualism in English and a Ghanaian language. We ask whether bilingualism in English and Ghanaian languages is a social handicap, without merit, or an important indicator of ethnic identity. Ghana has about 50 non-mutually intelligible languages, yet there are no statistics on who speaks what language(s) where in the country. We consider attitudes to English against the current Ghanaian language policy in education as practised in the school system. Our data reveal that parents believe early exposure to English enhances academic performance; English is therefore becoming the language of the home. Keywords: attitudes, English, ethnicity, Ghanaian languages, language policy Introduction Asanturofie anomaa, wofa no a, woafa mmusuo, wogyae no a, wagyae siadeé. (If you catch the beautiful nightjar, you inflict on yourself a curse, but if you let it go, you have lost something of great value). The attitude of Ghanaians to English is echoed in the paradox of this well-known Akan proverb. English might be a curse but it is at the same time a valuable necessity. Attitudes are learned, and Garret (2010) reminds us that associated with attitudes are ‘habits, values, beliefs, opinions as well as social stereotypes and ideologies’ (p.31). -

From the Sidelines to the Forefront Ensuring a Gender-Responsive Foundation for Liberia’S National Decentralization Process

From the Sidelines to the Forefront Ensuring a Gender-Responsive Foundation for Liberia’s National Decentralization Process: A Review and Analysis of Barriers, Opportunities and Entry Points A Study by the Governance Commission and Ministry of Gender and Development and UN Women February 2014 DEDICATION This study is dedicated to Sheelagh Kathy Mangones, UN Women Representative to Liberia, who sadly passed away on 4th February 2014 while attending an Africa regional meeting in Addis Ababa. Ms. Mangones was a humanitarian, dedicated to promoting the cause of women’s empowerment world-wide. Passionate about women’s participation at all levels, Kathy was committed to ensuring that Liberia’s decentralization opens new opportunities for Liberia’s rural women. This tribute is in recognition of her relentless efforts in promoting women’s empowerment and participation during her time in Liberia. She will be missed. Page 2 Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................................................................ 5 FOREWORDS ............................................................................................................................... 7 PREFACE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..8 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................ 9 DEFINITION OF KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS ................................................................................ 10 SECTION I: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ -

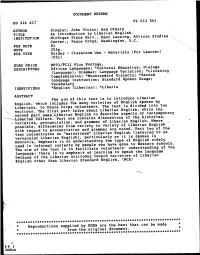

An Introduction to Liberian English

DOCUMENT RESUME FL 013 561 ED 226 617 AUTHOR Singler, John Victor; AndOthers An Introduction toLiberian English. TITLE Lansing. African Studies INSTITUTION Michigan State Univ.', East Center.; Peace Corps,Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 81 , NOTE 253p. 1 PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use -Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC11 Plus Postage. Education; Dialogs DESCRIPTORS African Languages; *Cultural (Language); Grammar; LanguageVariation; *Listening Comprehension; *NonstandardDialects; *Second Language,Instruction; Standard SpokenUsage; Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS *English (Liberian); *Liberia ABSTRACT The aim of this text is tointroduce Liberian English, which includes the manyvarieties of English spoken by Liberians, to Peace Corps volunteers.The text is dividedinto two sections. The first part talksabout Liberian English,while the sedond part uses LiberianEnglish to describe aspectsof contemporary --------Li-berfairdiature. Part one containsdiscussions of the histories, varieties, pronunciation, and grammarof Liberian English. Where possible, differences fromvariety to variety of LiberianEnglish and grammar are noted.1Parttwo of the with regard to pronunciation i(referred to as text concentrates on"mainstream" Liberian English vernacular Liberian English),particularly as it is spokenin Monrovia. Emphasis is onunderstanding the type of Englishwidely by people who have gone toWestern schools. used in informal contexts understanding of the The aim of the text is tofacilitate volunteers' language; there is no emphasison learning to speak the language because of the Liberianattitudes toward varieties ofLiberian English other than LiberianStandard English. (NCR) **********************************************************.************* the best that can be made * * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are * * from the original document. *********************************************************************** is Jr) VC) C\I CD 1.1.1 AN INTRODUCTION TO LIBERIAN ENGLISH BY JOHN VICTOR S I NGLER wi th J. -

Lntroduction

BerndKortmann and Kerstin Lunkenheimer lntroduction 1 Backgroundand history of this atlas This atlas offers a large-scaletypological survey of morphoslmtactic variation in the Anglophone world, basedon the analysisof 3OLl and 18indigenized L2varieties of English as well 25 English-basedpidgins and creolesfrom eight different world regions (Africa, Australia, the British Isles, the Caribbean,North America, the Pacific, South and SoutheastAsia and, as the borderline caseof an Anglophone world region, the South Atlantic). It is the outgrowth of a major electronic databaseand open accessresearch tool edited by the present editors in 2Oll (The electronicWord Atlas of Varietiesof English,short: eWAVEThttp://www.ewave- atlas.org/) and is a direct, but far more comprehensivefollow-up of the interactive CD-ROMaccompanying the Mouton de GruyterHandbook of Varietiesof English(Kortmann et al. 2oo4), Whereasthe grammar part of the latter survey was based on 75 morphoslmtacticfeatures in 46 varieties of English and English-based pidgins and creoles worldwide, its successor,the WAVEdatabase (WAVE short for: World Atlas of Vaiation in English),holds information on 235morphosyntactic features in74 datasets, i.e. about five times as much de- tail and information. The idea underlying the design of WAVEwas to createa considerablylarger and more @ fine-graineddatabase and researchtool than back in 20O4,especially one that is less Ll-centred. As a proper atlas should, WAVEis intended to survey and map the morphosyntacticvariation spacein the Anglophone world and to help us explore how much of this variation spaceis made use of in different (clustersof) varieties of English, and to what extent it is possibleto correlatethe structural profiles for indi- vidual and goups of varietieswith, for example, geography,socio-history or generalprocesses of language change,language acquisition and languagecontact. -

The Handbook of World Englishes

The Handbook of World Englishes THOA01 1 19/07/2006, 11:33 AM Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics This outstanding multi-volume series covers all the major subdisciplines within lin- guistics today and, when complete, will offer a comprehensive survey of linguistics as a whole. Already published: The Handbook of Child Language The Handbook of Language and Gender Edited by Paul Fletcher and Brian Edited by Janet Holmes and MacWhinney Miriam Meyerhoff The Handbook of Phonological Theory The Handbook of Second Language Edited by John A. Goldsmith Acquisition Edited by Catherine J. Doughty and The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Michael H. Long Theory Edited by Shalom Lappin The Handbook of Bilingualism Edited by Tej K. Bhatia and The Handbook of Sociolinguistics William C. Ritchie Edited by Florian Coulmas The Handbook of Pragmatics The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences Edited by Laurence R. Horn and Edited by William J. Hardcastle and Gregory Ward John Laver The Handbook of Applied Linguistics The Handbook of Morphology Edited by Alan Davies and Edited by Andrew Spencer and Catherine Elder Arnold Zwicky The Handbook of Speech Perception The Handbook of Japanese Linguistics Edited by David B. Pisoni and Edited by Natsuko Tsujimura Robert E. Remez The Handbook of Linguistics The Blackwell Companion to Syntax, Edited by Mark Aronoff and Janie Volumes I–V Rees-Miller Edited by Martin Everaert and The Handbook of Contemporary Syntactic Henk van Riemsdijk Theory The Handbook of the History of English Edited by Mark Baltin and Chris Collins Edited by Ans van Kemenade and The Handbook of Discourse Analysis Bettelou Los Edited by Deborah Schiffrin, Deborah The Handbook of English Linguistics Tannen, and Heidi E. -

Storytelling Traditions of Philadelphia's Liberian Elders

From West Africa to West Philadelphia Storytelling Traditions of Philadelphia’s Liberian Elders A Collaborative Project of The Center for Folklore and Ethnography University of Pennsylvania and The Agape African Senior Citizens Center 229 North 63rd Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Table of Contents Preface ....................................................................................................2 Liberia and the Philadelphia Community ........................................................5 Liberian Languages and Community Storytelling .............................................8 The Stories ...............................................................................................10 How Monkey Tricked Alligator by Edith Hill ....................................................10 Three Truths that Deer Told Leopard by John K. Jallah ..................................... 11 How the Animals Became Different Colors by Benjamin Kpangbah .......................12 Why Elephant is Afraid of Goat by Deddeh Passawee ........................................14 Greedy Spider by Ansumana Passawee .........................................................15 Which Brother Should Marry the King’s Daughter? by Ansumana Passawee ............16 Hawk and Hen by Edith Hill ........................................................................18 Which Wife Should Die? by Peter Sirleaf ........................................................19 Why Rabbit Sleeps When Leopard Chases Him by Deddeh Passawee .....................20 Leopard and -

The Myth of Reference Varieties in English Pronunciation Across the Subcontinent, Egypt and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

International Journal of English Linguistics; Vol. 5, No. 3; 2015 ISSN 1923-869X E-ISSN 1923-8703 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education The Myth of Reference Varieties in English Pronunciation across the Subcontinent, Egypt and Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Muhammad Khan1 1 Jazan University, Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Muhammad Khan, Jazan University, Jazan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 28, 2015 Accepted: April 21, 2015 Online Published: May 30, 2015 doi:10.5539/ijel.v5n3p19 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijel.v5n3p19 Abstract The present study aims at exploring the differences in pronunciation more or less prevailing in the Indian Subcontinent and Arab world with a special focus on Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt. The study identifies the most common factors that affect English pronunciation in general: (i) some phonemic differences that exist in L1 and English as a target language, (ii) Improper teaching and learning of English pronunciation. When non-native speakers of English exchange their ideas among themselves, their comprehension is to the maximum. But their pronunciation seems problematic in case the speaker or interlocutor is a native speaker. A test for the nationals of the lands included in the study was developed and administered to identify and specify the exact area(s) of pronunciation difficulties either consonants or vowels at segmental level of phonology. The analysis and conclusion of the test fully proved that English pronunciation is deeply influenced by the sound system of indigenous languages. As a matter of fact, English pronunciation of some non-native speakers, through their best possible efforts, may be closer to native speakers but not exactly like that of natives. -

Which English Dominates the World Wide Web, British Or American?

Which English Dominates the World Wide Web, British or American? Eric Atwell,1 Junaid Arshad,1 Chien-Ming Lai,1 Lan Nim,1 Noushin Rezapour Asheghi,1 Josiah Wang1 and Justin Washtell1 1. Introduction This paper reports the results of an experiment to combine research and teaching in Corpus Linguistics, using an AI-inspired intelligent agent architecture, but casting students as the intelligent agents (Atwell 2007). Computing students studying Computational Modelling and Technologies for Knowledge Management were given the data-mining coursework task of harvesting and analysing a Data Warehouse from WWW, using WWW-BootCat web-as-corpus technology (Baroni et al 2006). Each student/agent collected English-language web-pages from a specific national top-level domain, and the analysis task involved comparing their national web-as-corpus with given “gold standard” samples from UK and US domains, to assess whether national WWW English terminology/ontology was closer to UK or US English. Results from 93 countries worldwide were collated to give an overview answer to the question: Which English dominates the World Wide Web, British or American? 2. Methods The detailed coursework specification is given in Appendix A. The task was cast as an exercise in applying the CRISP-DM methodology for computational modelling: the Cross-Industry Standard Process for Data Mining projects. The CRISP-DM methodology specifies a series of phases or sub-tasks in a data-mining project; it is a “recipe” to follow, allowing novices and non-experts to carry out data mining experiments successfully. The students’ success in carrying out the exercise is a testament to the practical value of the CRISP-DM methodology. -

International English Usage Loreto Todd & Ian Hancock

INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH USAGE LORETO TODD & IAN HANCOCK London First published 1986 by Croom Helm This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge's collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” First published in paperback 1990 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE © 1986 Loreto Todd and Ian Hancock All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Todd, Loreto International English usage. 1. English language—Usage I. Title II. Hancock, Ian 428 PE1460 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Todd, Loreto. International English usage. Includes index. 1. English language—Usage—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Hancock, Ian F. II. Title. PE1460.T64 1987 428 86–28426 ISBN 0-203-97763-7 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-415-05102-9 (Print Edition) ISBN 0-709-94314-8 hb. Contents Introduction iv Contributors vi List of Symbols viii Pronunciation Guide ix INTERNATIONAL ENGLISH USAGE 1–587 Index 588–610 Introduction In the four centuries since the time of Shakespeare, English has changed from a relatively unimportant European language with perhaps four million speakers into an international language used in every continent by approximately eight hundred million people. It is spoken natively by large sections of the population in Australia, Canada, the Caribbean, Ireland, New Zealand, the Philippines, Southern Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States of America; it is widely spoken as a second language throughout Africa and Asia; and it is the most frequently used language of international affairs. -

The Taxonomy of Nigerian Varieties of Spoken English

Vol.5(9), pp. 232-240, November 2014 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2014.0623 Article Number: B500D5F47763 International Journal of English and Literature ISSN 2141-2626 Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Full Length Research Paper The taxonomy of Nigerian varieties of spoken English Oladimeji Kaseem Olaniyi Kwara State University, Malete, Nigeria. Received 05 June, 2014; Accepted 3 September, 2014 The dream of a Nigerian English dictionary has recently been actualized. The academic body of teachers and researchers known as NESA recently published a dictionary of the Nigerian English. The corpus of words and expressions in the dictionary represents the meaning and pronunciation of words as used by Nigerians.As a headlamp into the major and minor languages spoken by a vast population of Nigerians, this article seeks to stratify the varieties of Nigerian English on the basis of the popularity of the various ethnic groups which culminate in the variations that subsist in the accents of English available in Nigeria. As a result, in the first instance, a pyramid which classifies the over three hundred languages into three levels (in a pyramidal structure) is proposed. Secondly, coalesced phonemic inventories from all the varieties of Nigerian English are linguistically reconciled. From the methodology of the study to the findings, formal and informal interviews, perceptual and acoustic experiments carried out textually and inter-textually form the background of results which have been corroborated in the literatures of Nigerian English. This study is basically an appraisal of Nigerian English without any bias for the educated, uneducated, standard, or sub-standard varieties.