Americo-Liberians and the Transformative Geographies of Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A General Model of Illicit Market Suppression A

ALL THE SHIPS THAT NEVER SAILED: A GENERAL MODEL OF ILLICIT MARKET SUPPRESSION A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government. By David Joseph Blair, M.P.P. Washington, DC September 15, 2014 Copyright 2014 by David Joseph Blair. All Rights Reserved. The views expressed in this dissertation do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. ii ALL THE SHIPS THAT NEVER SAILED: A GENERAL MODEL OF TRANSNATIONAL ILLICIT MARKET SUPPRESSION David Joseph Blair, M.P.P. Thesis Advisor: Daniel L. Byman, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This model predicts progress in transnational illicit market suppression campaigns by comparing the relative efficiency and support of the suppression regime vis-à-vis the targeted illicit market. Focusing on competitive adaptive processes, this ‘Boxer’ model theorizes that these campaigns proceed cyclically, with the illicit market expressing itself through a clandestine business model, and the suppression regime attempting to identify and disrupt this model. Success in disruption causes the illicit network to ‘reboot’ and repeat the cycle. If the suppression network is quick enough to continually impose these ‘rebooting’ costs on the illicit network, and robust enough to endure long enough to reshape the path dependencies that underwrite the illicit market, it will prevail. Two scripts put this model into practice. The organizational script uses two variables, efficiency and support, to predict organizational evolution in response to competitive pressures. -

Remembering Alexander Crummell's Appeal to Postbellum

“WE NEED CHARACTER!”: Remembering Alexander Crummell’s Appeal to Postbellum African Americans LAURA GIMENO PAHISSA Institution address: Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona. Departament de Filologia Anglesa i de Germanística. Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres. Campus UAB. 08193 Bellaterra. Barcelona, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0002-3750-4769 Received: 31/01/2018. Accepted: 02/05/2018. How to cite this article: Gimeno Pahissa, Laura. “‘WE NEED CHARACTER!’: Remembering Alexander Crummell’s Appeal to Postbellum African Americans.” ES Review. Spanish Journal of English Studies, vol. 39, 2018, pp. 117‒33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.24197/ersjes.39.2018.117-133 Abstract: The following article offers a study and reassessment of the controversial figure of Alexander Crummell, an African American leader whose influence has been neglected by most scholars. His postbellum ideas on the advancement of black people influenced some of his contemporaries like Booker T. Washington and even later leaders such as W. E. B. DuBois. The article also offers an interpretation of two of Crummell’s most famous speeches on the future of his race, which suggest possible solutions to the tensions and problems experienced by his people after the end of the Civil War. Keywords: African American history; memory; slavery; American Civil War; Crummell; negro problem. Summary: Postbellum African American memory. Alexander Crummell: Advancement through character and morality. Conclusions. Resumen: Este artículo estudia y reexamina la figura del controvertido líder afroamericano Alexander Crummell, cuya influencia ha sido ignorada por muchos estudiosos. Sus ideas, escritas en la posguerra, sobre el progreso de los ciudadanos afroamericanos influyeron en algunos de sus contemporáneos como Booker T. -

Blacks on the Border: the Black Refugees in British North America, 1815-1900'

H-Canada Frost on Whitfield, 'Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815-1900' Review published on Tuesday, July 1, 2008 Harvey Amani Whitfield. Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815-1900. Burlington: University of Vermont Press, 2006. 200 pp. $24.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-58465-606-7; $65.00 (library), ISBN 978-1-58465-605-0. Reviewed by Karolyn Smardz Frost (Atkinson College School of Arts and Letters, York University) Published on H-Canada (July, 2008) Recreating the Black Refugees Blacks on the Border: The Black Refugees in British North America, 1815-1860 is a wonderful book. Far more than the sum of its parts, this slim volume focuses on several critical themes while expertly detailing the history of an important segment of the African Diaspora. Harvey Amani Whitfield, an assistant professor at the University of Vermont, demonstrates how African Americans from different parts of the United States, slave and free, who fought in the British forces in the War of 1812 came to found families, cultural institutions, and communities on Nova Scotia's inhospitable soil. He further details their subsequent development as a community and as a new, hybrid culture. This, Whitfield maintains, came about largely because of the hardships the so-called Black Refugees faced, not the least of which was the unrelenting and pervasively discriminatory treatment these brave and hardworking people encountered in their adopted Maritime home. The story of Nova Scotia's Black Refugees is generally less well known than that of the earlier migrants from the United States, the Black Loyalists. -

Design of Autonomous Coupling Mechanism for Modular Reconfigurable Lunar Rovers

Dartmouth College Dartmouth Digital Commons ENGS 88 Honors Thesis (AB Students) Other Engineering Materials Spring 6-6-2021 Design of Autonomous Coupling Mechanism for Modular Reconfigurable Lunar Rovers Christopher Lyke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/engs88 Part of the Engineering Commons Dartmouth Digital Commons Citation Lyke, Christopher, "Design of Autonomous Coupling Mechanism for Modular Reconfigurable Lunar Rovers" (2021). ENGS 88 Honors Thesis (AB Students). 30. https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/engs88/30 This Thesis (Senior Honors) is brought to you for free and open access by the Other Engineering Materials at Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in ENGS 88 Honors Thesis (AB Students) by an authorized administrator of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DESIGN OF AUTONOMOUS COUPLING MECHANISM FOR MODULAR RECONFIGURABLE LUNAR ROVERS by CHRIS LYKE Bachelor of Arts Honors Thesis Thayer School of Engineering Dartmouth College Hanover, New Hampshire Date: __________________________ Approved:______________________ Advisor’s Signature ______________________________ Author’s Signature Abstract Modular reconfigurable robotics consist of modules that can join together to form larger entities capable of changing their morphologies for improved versatility, robustness, and cost. Coupling mechanisms play a key role in these systems, as they are the component connecting the modules and enabling the robot to change shape. Coupling mechanisms also define the structure, rigidity, and function of modular systems. This paper details the development of the autonomous coupling mechanism for SHREWs, a modular reconfigurable system of rovers designed to explore the permanently shadowed regions of the Moon. -

Technical Memorandum

NASA Technical Memorandum NASA TM-82563 3EVELOPMEYT OF AN IMPROVED PROTECTIVE COVERILIGHT BLOCK FOR MULTlLAYEFi INSULATION By L. M. Thompson, Dr. J. M. S;uikey, Don Wilkes? 2nd Dr. Randy Humphries Materials arid Processes Laboratory October 1983 (YASA-TM-02503) DEYELOPHiiL? OF AN IYPBCVEI) B84- 15269 PROTECTIVE CQVEh/LIGHI BLCCK EGP MULTILAYEfi i&SiJLAl!IUAl (bASA) LO p HC A02/nP A01 CSCL 11E Unc~as Gr)/L7 1803b National keronauflcs and .Space Admr i;!rat $?r8 George C. Marshall Space Flight Center AISFC - Form 3190 (Rev. Msv 1983) TECdNICAL REPORT STANDARD TITLE PAGE 1. REPORT NO. 12. GOVERNmNT ACCESSION NO. 13. RECIPIENT'S CATALOG NO. NASA TM-825b3 I 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. REPORT DATE Development of an Inlproved hatective Cover/Llght October 1983 Block for Multdayer Insulation 6. PERFORMING 0RGANIZATIZ)N ClOE 7. AUTHm(S) L. M. Thompson, Dr. J. M. Stuckey, Don Wilkcs and 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT U Dr,dv Hunlphries -- 9. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME AND ADDRESS 10. WORK UNIT NO. I George C. Marshall Space Flight Center 1 1. CONTRACT OR GRANT NO. Marshall Space Flight Center, Alabama 358 12 13. TYPE OF REPOR; % PERIOD COVERED 12 SPONSORING AGENCY NAME AND ADORESS I Technical Memorandum National Aeronautics and Space Administration I Washington, D.C. 20546 1.1. SPONSORING AGENCY CODE I -l 15. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 1I 1 Prepared by Materials and Processes Laboratory. Science md Engineering This task was directed toward demonstrating the feasibilit~.of using a scrim-reinforced. single metallized. 4mil Tedlar film as a replacement for the Teflon coated Beta-c!oth/single metallized 3-mil Kapton film prexntly used as the protective coverllight block for multilayer insulation (MLI) on the Orbiter, Spacelab, and other space applications. -

Present State of Christianity, and of the Missionary Establishments For

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com PresentstateofChristianity,andthemissionaryestablishmentsforitspropagationinallpartsworld JohannHeinrichD.Zschokke,FredericShoberl,Zschokke ^SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSt Harvard College Library FROM THE BEQUEST OF Evert Jansen Wendell CLASS OF 1882 1918 c 3. & J. TTARPER, PRINTERS, 82 FfHF ffllilBMfHr! ITT PRESS, FOR THE TRADE, PELHAM; OR THE ADVENTURES OF A GEN TLEMAN. A Novel. In 2 vols. 12mo. 14 If the most brilliant wit, a narrative whose interest never flags, and some pictures of the most rivetting interest, can make a work popular, " Pelham" will he as first rate in celebrity as it is in excellence. The scenes are laid at the present day, and in fashionable life." — London Literary Gazette. THE SUBALTERN'S LOG-BOOK ; containing anecdotes of well-known Military Characters. In two vols. 12mo. In Press, for the Trade. DOMESTIC DUTIES ; or, Instructions to young Married Ladies, on the Management of their Households and the Regulation of their Conduct in the various relations and duties of Married Life. By Mrs. William Parkes. PRESENT STATE OF CHRISTIANITY, and of the Mis sionary Establishment for its propagation in all parts of the World. Edited by Frederic Shoberl. 12ano. HISTORY OF THE CAMPAIGNS OF THE BRITISH ARMIES in Spain, Portugal, and the South op France, from 1 308 to 1 8 14. By the Author of " Cyri! Thornton." GIBBON'S ROME, with Maps, Portrait, and Vignette Ti tles. 4 vols. 8vo. CROCKFORD'S LIFE IN THE WEST ; or, THE CUR TAIN DRAWN. -

A Case Study from Myanmar How to Inform, Empower, and Impact Communities

INFORMATION ECOSYSTEMS in transition: A case stUDY from myanmar HOW to inform, emPOWer, anD imPact commUnities Mon State, Myanmar Pilot Study PART ONE: RESEARCH FINDINGS ABOUT THE AUTHORS ABOUT THE RESEARCH TEAM EXecUtiVE SUmmary Andrew Wasuwongse is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins Established in 1995, Myanmar Survey Research (MSR) University’s School of Advanced International Studies in is a market and social research company based in Washington, DC. He holds a master’s degree in International Yangon, Myanmar. MSR has produced over 650 Relations and International Economics, with a concentration research reports in the fields of social, market, and in Southeast Asia Studies. While a research assistant for environmental research over the past 16 years for UN the SAIS Burma Study Group, he supported visits by three agencies, INGOs, and business organizations. Burmese government delegations to Washington, DC, including officials from Myanmar’s Union Parliament, ABOUT INTERNEWS in MYANMAR Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Industry. He has worked as a consultant for World Vision Myanmar, where he led an Internews is an international nonprofit organization whose assessment of education programs in six regions across mission is to empower local media worldwide to give people Myanmar, and has served as an English teacher in Kachin the news and information they need, the ability to connect State, Myanmar, and in Thailand on the Thai-Myanmar border. and the means to make their voices heard. Internews He speaks Thai and Burmese. provides communities with the resources to produce local news and information with integrity and independence. Alison Campbell is currently Internews’ Senior Director With global expertise and reach, Internews trains both media for Global Initiatives based in Washington, DC, overseeing professionals and citizen journalists, introduces innovative Internews’ environmental, health and humanitarian media solutions, increases coverage of vital issues and helps programs. -

C a L L a L O O

C A L L A L O O WHAT WE MEAN WHEN WE SAY ‘CREOLE’ An Interview with Salikoko S. Mufwene by Michael Collins Salikoko S. Mufwene is an internationally renowned theorist of language evolution, language contact, and sociolinguistics, among other subjects. He sat for the following interview on April 7 and April 8, 2003, during a visit he paid to Texas A & M University in College Station to lecture on controversies surrounding Ebonics. Mufwene’s ability to dazzle audiences was just as evident in Texas as it had been in the city-state of Singapore, where I first heard him lecture. His ability was indeed already apparent early in his life in Congo: Robert Chaudenson of the Université d’Aix-en-Provence reports that in 1973 “Mufwene received a License en Philosophie et Lettres (with a major in English Philology) from the National University of Zaire at Lubumbashi (with Highest Honors). The same year he also obtained his Agrégation d’enseignement moyen du degré supérieur (with Honors). Let me comment a bit on the significance of these diplomas, especially for readers who are not familiar with (post)colonial Africa. That the young Salikoko, born in Mbaya-Lareme, would find himself twenty years later in Lubumbashi at the University, with not one but two diplomas, should in itself count as an obvious sign of intellectual excellence for anyone who is in any way familiar with the Congo of that era. Salikoko must have seriously distinguished himself among his peers: at that time, overly limited opportunities and a brutally elitist educational system did entail fierce competition.” For the rest of Chaudenson’s remarks, and for further information on Mufwene, see http://humanities.uchicago.edu/faculty/mufwene/index.html. -

African American Elitism: a Liberal and Quantitative Perspective by Chieke Ihejirika, Ph.D

African American Elitism: A Liberal and Quantitative Perspective by Chieke Ihejirika, Ph.D. Abstract According to Edmund Burke the British philosopher generally regarded as the father of conservatism, this principle is all about preserving the status quo or, at least, the avoidance of radical or unstructured changes. This agrees with the saying that “if it aint broke don’t fix it,” implying that an unnecessary change must be avoided. Yet very few can question the universal veracity of the assertion that the more satiated members of any society tend to be more conservative than other members of that society. In fact, the most comfortable members would prefer no changes at all because of the fear that uncontrolled changes might have an adverse affect on them. Members of the Black community are very familiar with the censure that successful Blacks in America simply move to the mainline, start acting like the haves and forget the folks they left behind in the inner city. The need to establish or reject the efficacy of this denunciation provides the impetus for this study. This article attempts to validate or nullify the truth of this criticism, by investigating the hypothesis that high income always leads to greater conservatism among African-Americans, just as in White Americans. The study discovers that although middle class Blacks tend to move out of the inner city areas, they remain very sympathetic to many liberal values or issues they believe would be uplifting to their less privileged people, quite unlike their White counterparts. This study curiously exposes the fact that upper class Blacks are more liberal than upper class Whites and lower class Blacks. -

From Twitter

H-Slavery From Twitter Discussion published by Amanda McGee on Sunday, September 8, 2019 This week in the twittersphere, the Dalhousie University offered an apology to Black Nova Scotians for its role in the Atlantic Slave trade and its historical ties to slavery. Learn more here. A piece by the Liberty Africa Writers highlights an enslaved Ghanaian woman named Breffu who led a revolt against the Danish army stationed in the West Indies in 1733. Read more about Breffu’s revolt here. A new podcast episode by Teaching Tolerance explores the relationship between the institution of slavery and indigenous populations in North America. The episode, "Indigenous Enslavement," is hosted by Hasan Kwame Jeffries and Meredith McCoy and features an interview with Christina Snyder who discusses how European invasion changed indigenous ideas about bondage. Find the episode here. In her article, “A Downtown Jackson Alley Was Renamed After a Woman Who Escaped Slavery," Sarah Clinkscales details the renaming and transformation of a street in Jackson City, Michigan, to honor Emma Nichols, an enslaved woman who came to the city on the Underground Railroad. Learn more here. Also this week, The 1619 Project published its second podcast episode, “The Economy that Slavery Built." In it, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Jesmyn Ward, and Matthew Desmond investigate the relationshjp between American Capitalism and the brutality of slavery on the plantation. Listen to the episode or read the transcript here. Citation: Amanda McGee. From Twitter. H-Slavery. 09-08-2019. https://networks.h-net.org/node/11465/discussions/4654441/twitter Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. -

Download Download

VOLUME I OCTOBER 1968 NUMBER 1 JSHED BY THE AFRICAN STUDIES CENTER, REPAUW UNIVERSITY, GREENCASTLE, INDIANA - VOLUME I Fall 1968 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Edited by: Svend E. Holsoe , DePauw University David M. Foley, University of Georgia Published at the African Studies Center, DePauw University CONTENTS THE KPELLE TRADITIONAL POLITICAL SYSTEM, by Richard M. Fulton CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE 19 FIELD NOTES ON TRIBAL MEDICAL PRACTICES IN CENTRAL LIBERIA, by Kenneth G. Orr TWO HISTORICAL MANUSCRIPTS FROM THE KRU COAST, by Ronald W. Davis A. A. ADEE'S JOURNAL OF A VISIT TO LIBERIA IN 182 7, by George E . Brooks, Jr . THE TUBMAN CENTER OF AFRICAN CULTURE, by Kjell Zetterstrom Emphasizing the social sciences and humanities, the Liberian Studies Journal is a biannual publication devoted to studies of Africa's oldest republic. Copyright 1968 by The Liberian Studies Association in America. Manuscripts, correspondence and subscriptions should be sent to: Liberian Studies Journal, African Studies Center, DePauw University, Greencastle, Indiana 4 6135 . THE KPELLE TRADITIONAL POLITICAL SYSTEM Richard M. Fulton The Kpelle are the largest tribal group in Liberia, numbering around 150,000. Residing in the central interior of the country, rcughly between the St. Paul and St. John Rivers, they were amongst the last tribal units to be pacified by the central-modernizing government. Since thls paciii- cation program was only completed in the early 19201s, the Kpelle offer a good opportunity to investigate the primitive system that perservered, on the whole, until that time. Remarkably little has been written on the Kpelle as such and almost nothing on their traditional political system.' This effort is part of a larger attempt on the part of the author to trace the development of the political change amongst the Kpelle researched while in Liberia teaching at Cuttington College (October, 1966- July, 1967). -

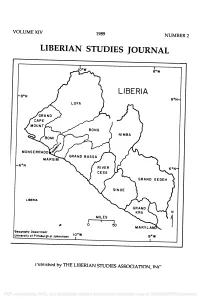

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L.