Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Programs in Post-Conflict Environments: a Review from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Africa 1

Revista Electrónica Educare ISSN: 1409-4258 ISSN: 1409-4258 Universidad Nacional. CIDE Education Programs in Post-Conflict Environments: a Review from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Africa 1 Barrios-Tao, Hernando; Siciliani-Barraza, José María; Bonilla-Barrios, Bibiana 1 Education Programs in Post-Conflict Environments: a Review from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Africa Revista Electrónica Educare, vol. 21, no. 1, 2017 Universidad Nacional. CIDE Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=194150012011 DOI: 10.15359/ree.21-1.11 PDF generated from XML Redalyc JATS4R Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Artículo Original Education Programs in Post-Conflict Environments: a Review from Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Africa 1 Programas de Educación en escenarios de posconflicto: Una revisión de Liberia, Sierra Leona y Suráfrica Hernando Barrios-Tao 1 [email protected] Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, Colombia hp://orcid.org/000-0002-8999-0586 José María Siciliani-Barraza 2 [email protected] Universidad de la Salle, Colombia hp://orcid.org/0000-0002-9639-2277 Bibiana Bonilla-Barrios 3 [email protected] Universidad del Rosario, Colombia hp://orcid.org/0000-0003-0793-8758 Abstract: Education should be considered as one of the mechanisms for governments and nations to succeed in a post-conflict process. e purpose of this Review Article is twofold: to explain the importance of education in a post-conflict setting, and to describe a few strategies that post-conflict societies have implemented. In terms of research design, a multiple case study approach has been implemented. e paper reviews a unique topic with specific reference to education plans implemented in post-conflict Revista Electrónica Educare, vol. -

OARE Participating Academic Institutions

OARE Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Herat Rizeuldin Research Institute And Medical Hospital HERAT UNIVERSITY Health Clinic of Herat University Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Afghanistan Rehabilitation And Development Center Alfalah University 19-Dec-2017 3:14 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 194 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul Ministry of Higher Education Afghanistan Biodiversity Conservation Program Afghanistan Centre Cooperation Center For Afghanistan (cca) Ministry of Transport And Civil Aviation Ministry of Urban Development Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Emergency NGO - Afghanistan French Medical Institute for children, FMIC Kabul University. Central Library American University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Afghanistan National Public Health Institute, ANPHI Kabul Education University Allied Afghan Rural Development Organization (AARDO) Cheragh Medical Institute Kateb University Afghan Evaluation Society Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Information and Communication Technology Institute (ICTI) Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan Kabul Medical University Isteqlal Hospital 19-Dec-2017 3:14 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 194 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan -

Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia

‘Listen, Politics is not for Children:’ Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henryatta Louise Ballah Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Drs. Ousman Kobo, Advisor Antoinette Errante Ahmad Sikianga i Copyright by Henryatta Louise Ballah 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the historical causes of the Liberian civil war (1989- 2003), with a keen attention to the history of Liberian youth, since the beginning of the Republic in 1847. I carefully analyzed youth engagements in social and political change throughout the country’s history, including the ways by which the civil war impacted the youth and inspired them to create new social and economic spaces for themselves. As will be demonstrated in various chapters, despite their marginalization by the state, the youth have played a crucial role in the quest for democratization in the country, especially since the 1960s. I place my analysis of the youth in deep societal structures related to Liberia’s colonial past and neo-colonial status, as well as the impact of external factors, such as the financial and military support the regime of Samuel Doe received from the United States during the cold war and the influence of other African nations. I emphasize that the socio-economic and political policies implemented by the Americo- Liberians (freed slaves from the U.S.) who settled in the country beginning in 1822, helped lay the foundation for the civil war. -

Semi-Weekly Interafrican News Survey

SEMI-WEEKLY INTERAFRICAN NEWS SURVEY .. '"t'!'P'•-a.. ;_ac:zazaac-- .z ~-- .. I""'V!".~ · Crganization of African Unity · LID0/\£1Y j I ( 12 DEC1980 ] IOrg•nisation de /'UIIIIe ~/ne BIBLIOTHEQUE . MONTHLY SUBSCRIPTION FEE (fiiTHOUT REPRODUCTION RIGHTS) FRENCH FRAi.CS:225 (AIR MAIL POSTAG' CHARGES EXCLUDED) 11,13,15, PLACE DE LA BOURSE 71o02 PARIS TEL: 233.44.18 TELEX 210084 DATE December. 2; 1980 I I • Indlpe.ndmmre.n.t de 4an 4e~t.vke d' In0aiUIIa..tlan.b gbttutu, I.' AGCNCE FTWICE-PRE.S.Sc cUaoUAe, dan4 tou.te. lt:. F~tanc.e. e.t dan4 c.~ 'fXl.l/4 e.uMpl~, wt "Se~t.v.i.c.e d.' .i.n6a1UIIttUon.b Ec.arwmi.ou.u Po/L TUeACJLi.:ptewr.l' (S. E. f. I . L'A.F.P. pubtie, d.'~e. p~, tu but!etin4 4pleia U.4~ 4u.i.vant4 : BULLETIN Q.UOT!fJIEN 1)' INFORMATIONS T'EXT!LES BULLET!N QUOT!fJ!EN f)'AFRIQUE BULLET!N QUOTitJ!EN tJ' INFORMATIONS RELIGIEUSES AUTO- IUOUS7"'RIES . (qu.a.ti.d.i.en) A.F.P.-SCIE~CES (hebdom~e) CACAOS, CAFES, SUCRES ( he.bdomada.Ut.e.) AFRICA ( b.i..-he.bdcmada.Ut.e., en ang.ta.i4) SAHARA ( b.i.-m~u.dl CAH!ERS OE L' AFRI{!JE OCCIT]ENTALE ET OE L' AFRI®E EQ_UATOR.!:~LE ( b.i..-m~u.d.) 'POUif. toc:.4 JWt4 eigneme.n..Q ~ I !UVr.U4 e/t. a l'AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE 1 13, 1S, pla.c.e. de. I.a. 8outWe. -· ;sooz PARIS - Se~r.v..i.c.e. -

The Chair of the African Union

Th e Chair of the African Union What prospect for institutionalisation? THE EVOLVING PHENOMENA of the Pan-African organisation to react timeously to OF THE CHAIR continental and international events. Th e Moroccan delegation asserted that when an event occurred on the Th e chair of the Pan-African organisation is one position international scene, member states could fail to react as that can be scrutinised and defi ned with diffi culty. Its they would give priority to their national concerns, or real political and institutional signifi cance can only be would make a diff erent assessment of such continental appraised through a historical analysis because it is an and international events, the reason being that, con- institution that has evolved and acquired its current trary to the United Nations, the OAU did not have any shape and weight through practical engagements. Th e permanent representatives that could be convened at any expansion of the powers of the chairperson is the result time to make a timely decision on a given situation.2 of a process dating back to the era of the Organisation of Th e delegation from Sierra Leone, a former member African Unity (OAU) and continuing under the African of the Monrovia group, considered the hypothesis of Union (AU). the loss of powers of the chairperson3 by alluding to the Indeed, the desirability or otherwise of creating eff ect of the possible political fragility of the continent on a chair position had been debated among members the so-called chair function. since the creation of the Pan-African organisation. -

Administration International Studies

InternationalAdministration Studies in Educational Administration Journal of the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration & Management CCEAM Volume 48 Number 1 2020 International Studies in Educational Administration by the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration and Management (CCEAM). Details of the CCEAM and its affiliated national societies throughout the Commonwealth are given at the end of this issue. Enquiries about subscriptions and submissions of papers should be addressed to the editor, Associate Professor David Gurr via email at: [email protected]; website: www.cceam.org. Commonwealth Members of CCEAM receive the journal as part of their membership. Other subscribers in Commonwealth countries receive a discount, and pay the Commonwealth rates as stated below. Payment should be made to the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration and Management (CCEAM). The rest of the world Subscribers in the rest of the world should send their orders and payment to the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration and Management (CCEAM). Account details for all payments are as follows Account name: Canadian Association for the Study of Educational Administration c/o Dr. Patricia Briscoe Bank: Royal Bank of Canada, 2855 Pembina Hwy – Unit 26, Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2H5 Institution number: 003 Transit number: 08067 Account number: 1009232 Swift code: ROYCCAT2 Subscription rates for 2020 Institutions, Commonwealth £150 Institutions, rest of world £170 Individuals, Commonwealth £30 Individuals, rest of world £35 © CCEAM, 2020 International Studies in Educational Administration Journal of the Commonwealth Council for Educational Administration & Management Volume 48 ● Number 1 ● 2020 International Studies in Educational Administration Professor Alma Harris, Director of the Institute (ISEA) for Educational Leadership, University of Malaya An official publication of the Commonwealth Council MALAYSIA for Educational Administration and Management Dr A.A.M. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Shadow Colony: Refugees and the Pursuit of the Liberian

© COPYRIGHT by Micah M. Trapp 2011 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SHADOW COLONY: REFUGEES AND THE PURSUIT OF THE LIBERIAN- AMERICAN DREAM BY Micah M. Trapp ABSTRACT This dissertation is about the people living at the Buduburam Liberian refugee camp in Ghana and how they navigate their position within a social hierarchy that is negotiated on a global terrain. The lives of refugees living in Ghana are constituted through vast and complex social relations that span across the camp, Ghana, West Africa and nations further afield such as the United States, Canada and Australia. The conditions under which these relations have developed and continue to unfold are mediated by structural forces of nation-state policies, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the international governing body for refugees, and the global political economy. Situated within the broader politics of protracted refugee situations and the question of why people stay in long-term camps, this research is a case study of one refugee camp and how its people access resources, build livelihoods and struggle with power. In particular, this dissertation uses concepts of the Liberian-American dream and the shadow colony to explore the historic and contemporary terms and circumstances ii through which Liberian refugees experience and evaluate migratory prospects and restrictions. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The production of this dissertation has been an outcome of many places and people. In Washington, DC my committee members, Dolores Koenig, Geoffry Burkhart, and David Vine have provided patient support and provocative feedback throughout the entire process. Thank you for asking the right questions and reading so many pages. -

Reenvisioning Postconflict Reconstruction and Education in Rural Liberia

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2019 Empowering children's social ecology: Reenvisioning postconflict reconstruction and education in rural Liberia Kristen N. McNutt University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2019 Kristen N. McNutt Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Elementary Education Commons Recommended Citation McNutt, Kristen N., "Empowering children's social ecology: Reenvisioning postconflict econstructionr and education in rural Liberia" (2019). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 952. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/952 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by KRISTEN N. MCNUTT 2019 All Rights Reserved EMPOWERING CHILDREN’S SOCIAL ECOLOGY: REENVISIONING POSTCONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION AND EDUCATION IN RURAL LIBERIA An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Kristen N. McNutt University of Northern Iowa May 2019 ABSTRACT Despite the Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement calling the end to Liberia’s back-to-back civil wars in 2003, Liberia’s peace remains fragile with a high number of out of school children, especially in rural communities. As an indicator of state fragility, rural education needs to be a priority in post-conflict reconstruction. This thesis emerged to support the nongovernmental organization, Supporting Programs in Community Empowerment (SPICE), an emerging Liberian-based nongovernmental organization. -

UMU INFO BROCHURE -2018.Cdr

The United Methodist University of Liberia 508-C-17 Centennial Area, Ashmun Street 1000 Monrovia 10, Liberia, West Africa ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- LAC-UMC LIBERIA “A LIGHT TO THE WORLD” ESTABLISHED 1998 2019 United Methodist University Liberia Project ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- ----- LAC-UMC LIBERIA “A LIGHT TO THE WORLD” ESTABLISHED 1998 Front view of the Multipurpose Classrooms & Office Complex Building Courtyard MAJOR FEATURES OF THE MULTIPURPOSE CLASSROOMS AND OFFICE COMPLEX BUILDING Descriptions Space/ Rooms 10. Conference Rooms 3 1. Instructional Classrooms 80 (With 6 Bathrooms) 2. Information Technology Labs 2 11. Bathrooms (Staff) 48 3. Computer Labs (General) 3 12. Bathrooms (Students) 54 4. Science Laboratories 4 13. Auditorium 1 (Biology/ Chemistry/ Physics) 14. Cafeteria 1 5. Library 1 15. Student Center 1 6. Clinic 1 16. Kitchen 1 7. Reading/ Study Rooms 2 17. Courtyards 2 8. Offices 33 18. Elevators 2 9. Teacher Lounges 3 Message From The Ofce of Institutional Development and Advancement Dear Students, Families, Friends, and Partners: It is our pleasure to share the 2018 brochure with you students, families, friends, and partners. We want to ensure that our stakeholders have pertinent information about the United Methodist University in Liberia. The United Methodist University is a co-education Christian institution of higher learning serving a diverse student population. The United Methodist University offers diploma, associate, bachelor, and master degree programs in several disciplines within seven (7) colleges: (College of Education, College of Health Sciences, College of Theology, College of Management and Administration, College of Liberal and Fine Arts, College of Science and Technology, the College of Agriculture), and the Rev. Dr. -

Liberian Studies Journal

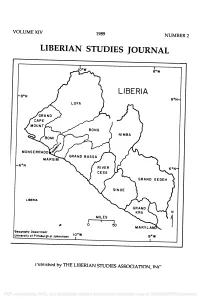

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L. -

17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2020 World Englishes and their dialect roots Schreier, Daniel Abstract: This chapter investigates the persistence and development of so-called dialect roots, that is, features of local forms of British English that are transplanted to overseas territories. It discusses dialect input and the survival of features, independent developments within overseas communities, including realignments of features in the dialect inputs, as well as contact phenomena when English speakers interact with those of other dialects and languages. The diagnostic value of these roots is exemplified with selected cases from around the world (Newfoundland English, Liberian English, Caribbean Englishes), which are assessed with reference to the archaic/dynamic character of individual features in new-dialect formation and language-contact scenarios. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-198161 Book Section Published Version The following work is licensed under a Publisher License. Originally published at: Schreier, Daniel (2020). World Englishes and their dialect roots. In: Schreier, Daniel; Hundt, Marianne; Schneider, Edgar W. The Cambridge Handbook of World Englishes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 384-407. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108349406.017 17 World Englishes and Their Dialect Roots Daniel Schreier World Englishes developed out of English dialects spoken throughout the British Isles. These were transported all over the globe by speakers from different regions, social classes, and educational backgrounds, who migrated with distinct trajectories, for various periods of time and in distinct chronolo- gical phases (Hickey, Chapter 2, this volume; Britain, Chapter 7,thisvolume).