Vasari. Preface to Part Three of the Lives of the Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observing Protest from a Place

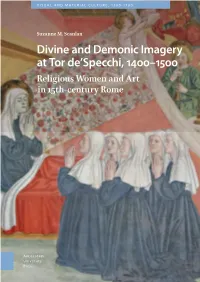

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

PRESENT IN THE PERFORMANCE: STEFANO MADERNO’S SANTA CECILIA AND THE FRAME OF THE JUBILEE OF 1600 by KELLY ANNE WHITFORD A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kelly Anne Whitford Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Dr. James Harper Chairperson Dr. Nicola Camerlenghi Member Dr. Jessica Maier Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2011 ii © 2011 Kelly Anne Whitford iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kelly Anne Whitford Master of Arts Department of Art History December 2011 Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 In 1599, in commemoration of the remarkable discovery of the incorrupt remains of the early Christian martyr St. Cecilia, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrato commissioned Stefano Maderno to create a memorial sculpture which dramatically departed from earlier and contemporary monuments. While previous scholars have considered the influence of the historical setting on the conception of Maderno’s Santa Cecilia, none have studied how this historical moment affected the beholder of the work. In 1600, the Church’s Holy Year of Jubilee drew hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to Rome to take part in Church rites and rituals. -

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Giorgio Vasari Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Table of Contents Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects.......................................................................1 Giorgio Vasari..........................................................................................................................................2 LIFE OF FILIPPO LIPPI, CALLED FILIPPINO...................................................................................9 BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO........................................................................................................13 LIFE OF BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO.........................................................................................14 FRANCESCO FRANCIA.....................................................................................................................17 LIFE OF FRANCESCO FRANCIA......................................................................................................18 PIETRO PERUGINO............................................................................................................................22 LIFE OF PIETRO PERUGINO.............................................................................................................23 VITTORE SCARPACCIA (CARPACCIO), AND OTHER VENETIAN AND LOMBARD PAINTERS...........................................................................................................................................31 -

Hercules: Flawed and Fixed

Hercules: Flawed and Fixed An Aristotelian Problem with a Kinesic Solution In Medici Florence Honors Thesis in the Department of Art History University of Oregon Cassidy Shaffer Spring 2019 The Medici family of Florence used Hercules as a dynastic symbol to project ideas of courage and strength onto the family. However, because Hercules is a deeply flawed character throughout the entirety of his story, the Medici needed to manipulate how people perceived the hero by commissioning sculpture that would reflect the desired moral values and courageous virtue. Florence was ruled by the Medici family for three centuries beginning with the return of Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici from exile in 1434.1 During these three centuries, the Medici family used the artistic innovation of the Florentine renaissance to profit politically. Beginning with Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici, large-scale Medici patronage of the arts continued steadily throughout the remainder of the 15th and 16th centuries within the family. Their commissions were often used to demonstrate the family’s wealth, status, religious beliefs, interests, and culture. They largely conveyed themes such as fortitude, piety, leadership, righteousness, and courage. Two of the most prominent figures used to present these concepts were the biblical David and the mythical Hercules. Adopted to the city’s seal in 12812, Hercules became a symbol of Florence and connected the city with these same virtues later indexed in Medici commissions. The Medici adopted the iconography of the hero Hercules as not only an expression of their family’s values, but also an articulation of what life in Florence would be like under Medici influence; through Hercules they projected themselves as quintessentially Florentine. -

ARTH206-Giorgio Vasari-Lives of the Most Emminent

Selections from Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors & Architects Giorgio Vasari, Translated by Gaston Du C. De Vere (1912-14) Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 1 of 199 LIVES OF THE MOST EMINENT PAINTERS SCULPTORS & ARCHITECTS 1912 BY GIORGIO VASARI: NEWLY TRANSLATED BY GASTON Du C. DE VERE. WITH FIVE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS: IN TEN VOLUMES LONDON: MACMILLAN AND CO. LD. & THE MEDICI SOCIETY, LD. 1912-14 CONTENTS Volume 1 3 Dedications to the Cosimo Medici 4 The Author’s Preface to the Whole Work 7 Giovanni Cimabue 19 Niccola and Giovanni of Pisa 31 Giotto 50 Ambrogio Lorenzetti 78 Volume 2 83 Duccio 84 Paolo Ucello 90 Lorenzo Ghiberti 100 Masolino Da Panicale 121 Masaccio 126 Filippo Brunelleschi 136 Donato [Donatello] 178 Volume 1 Footnotes 198 Volume 2 Footnotes 199 Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 2 of 199 VOLUME I Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 3 of 199 DEDICATIONS TO COSIMO DE' MEDICI TO THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND MOST EXCELLENT SIGNOR COSIMO DE' MEDICI, DUKE OF FLORENCE AND SIENA MY MOST HONOURED LORD, Behold, seventeen years since I first presented to your most Illustrious Excellency the Lives, sketched so to speak, of the most famous painters, sculptors and architects, they come before you again, not indeed wholly finished, but so much changed from what they were and in such wise adorned and enriched with innumerable works, whereof up to that time I had been able to gain no further knowledge, that from my endeavour and in so far as in me lies nothing more can be looked for in them. -

Engaging Symbols

Engaging Symbols GENDER, POLITICS, AND PUBLIC ART IN FIFTEENTH-CENTURY FLORENCE Adrian W.B. Randolph Yale University Press New Haven and London Copyright © 2002 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Leslie Fitch Set in Fournier and Futura type by Leslie Fitch Printed in Italy at Conti Tipocolor Libiury of Congress Cataloging-in- PuBLiCATiON Data Randolph, Adrian W. B., 1965- Engaging symbols: gender, politics, and public art in fifteenth-century Florence/ Adrian W. B. Randolph, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-300-09212-1 I. Art, Italian—Italy—Florence— 15th century. 2. Gender identity in art. 1. Title. N6921.F7 R32 2002 709'.45*51090 24—dc2i 2001008174 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 987654321 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Florence, Inc. i 1 Common Wealth: Donatello’s Ninfa Fiorentina 19 2 Florentia Figurata 76 3 Engaging Symbols: Legitimacy, Consent, and the Medici Diamond Ring 108 4 Homosocial Desire and Donatello’s Bronze David 139 5 Spectacular Allegory: Botticelli’s Pallas Medicea and the Joust of 1475 193 6 O Puella Furax: Donatello’s Judith and Holofernes and the Politics of Misprision 242 Notes 287 Bibliography 339 Index 375 Photography Credits 381 4 Homosocial Desire and Donatello’s Bronze David El Davit della cone e una figura et non e perfecta, perche la gamba sua di drieto e schiocha. -

Early Masters of Italian Renaissance Painting Fall 2018 Syllabus

Semester: Fall 2018 Full Title of Course: Early Masters of Italian Renaissance Painting Alpha-Numeric Class Code: ARTH-UA9306001 Meeting Days and Times: Tuesdays, h13:00-16:00 PM Classroom Location: Villa Sassetti,Aula Caminetto Class Description: Prerequisite: ARTH-UA 2, History of Western Art II, ARTH-UA 5, Renaissance and Baroque Art, or equivalent introductory art history course or a score of 5 on the AP Art History exam. This course is conceived as a series of selected studies on early Renaissance painting, offering in- depth analysis of the historical, political and cultural evolution of Italy and Europe between the 14th and the 15th centuries. This overview will be not confined to works of painting but will include social and patronage issues - i.e. the role of the guilds, the differences in private, civic and church patronage - that affected the style, form and content of the Italian rich artistic output, which reached a peak often nostalgically referred to by later generations as the “dawn of the Golden Age”. Themes such as patronage, humanism, interpretations of antiquity, and Italian civic ideals form a framework for understanding the works of art beyond style, iconography, technique, and preservation. Special attention will be given to the phenomenon of collecting as an active force in shaping the development of artistic forms and genres. By the end of this course, students gain a thorough knowledge of the Italian and European early Renaissance age, developing practical perception and a confident grasp of the material, understanding the relationship between both historical and artistic events and valuing the importance of patronage. -

AH II Slide List

ARTS 1304! 1 Slide List Fall 2012 Fourteenth Century Art in Europe 1. Frescoes of the Sala Dei Nove, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 14th Century 2. Life of John the Baptist, Andrea Pisano, 14th Century 3. Virgin and Child Enthroned, Giotto, 14th Century 4. Scrovengi (Arena) Chapel, Giotto, 14th Century 5. Lamentation and Resurrection, Giotto, 14th Century 6. Virgin and Child Enthroned (Rucellai Madonna), Duccio, 14th Century 7. Raising of Lazarus, Duccio, 14th Century 8. The Effects of Good Government in the City and in the Country, Ambrogio Lorenzetti, 14th Century 9. Exeter Cathedral, 14th Century 10. Pietà (Vesperbild), 14th Century 11. St Luke, Master Theodoric, 14th Century Renaissance Art in Fifteenth Century Italy 12. Dome of Florence, Fillipo Brunelleschi, Renaissance 13. David, Donatello, Renaissance 14. “Gates of Paradise”, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Renaissance 15. The Battle of the Nudes, Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Renaissance 16. The Delivery of the Keys to St. Peter, Perugino, Renaissance 17. The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, Masaccio, Renaissance 18. The Battle of San Romano, Paolo Uccello, Renaissance 19. The Last Supper, Andrea del Castagno, Renaissance 20. The Baptism of Christ, Piero della Francesca, Renaissance 21. Scenes from the Life of St. Francis, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Renaissance 22. Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli, Renaissance 23. Primavera, Sandro Botticelli, Renaissance 24. St. Francis in Ecstasy, Giovanni Bellini, Renaissance Fifteenth Century Art in Northern Europe 25. Double Portrait of a Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife (aka The Arnolfini Portriat), Jan Van Eyck, Northern Renaissance 26. February, Life in the Country, Très Riches Heures, Paul, Herman, and Jean Limbourg, Northern Renaissance 27. -

Michael Angelo Buonarroti by Charles Holroyd

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Michael Angelo Buonarroti by Charles Holroyd This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.guten- berg.org/license Title: Michael Angelo Buonarroti Author: Charles Holroyd Release Date: September 19, 2006 [Ebook 19332] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MICHAEL ANGELO BUONARROTI*** Michael Angelo Buonarroti By Charles Holroyd, Keeper of the National Gallery of British Art, with Transla- tions of the Life of the Master by His Scholar, Ascanio Condivi, and Three Dialogues from the Portuguese by Francisco d'Ollanda London Duckworth and Company New York Charles Scribner's Sons 1903 MICHAEL ANGELO From an early proof of the engraving by GIULIO BONASONI (In the Print Room of the British Museum) Contents Preface . ix Illustrations . xii PART I . 1 CHAPTER I . 3 CHAPTER II . 19 CHAPTER III . 25 CHAPTER IV . 29 CHAPTER V . 37 CHAPTER VI . 39 CHAPTER VII . 47 CHAPTER VIII . 51 CHAPTER IX . 61 CHAPTER X . 67 CHAPTER XI . 71 PART II . 85 CHAPTER I . 87 CHAPTER II . 99 CHAPTER III . 107 CHAPTER IV . 125 CHAPTER V . 131 CHAPTER VI . 141 CHAPTER VII . 189 CHAPTER VIII . 203 CHAPTER IX . 233 CHAPTER X . 249 CHAPTER XI . 277 APPENDIX . 285 FIRST DIALOGUE . 287 SECOND DIALOGUE . 305 viii Michael Angelo Buonarroti THIRD DIALOGUE . 320 THE WORKS OF MICHAEL ANGELO . 343 A LIST OF THE PRINCIPAL BOOKS CONSULTED BY THE AUTHOR . -

FINE ARTS 344 - EARLY ITALIAN RENAISSANCE ART COURSE SYLLABUS – FALL SEMESTER 2017 INSTRUCTOR: John Nicholson Meeting: Tuesday – Thursday, 2:20 – 3:35 Pm

FINE ARTS 344 - EARLY ITALIAN RENAISSANCE ART COURSE SYLLABUS – FALL SEMESTER 2017 INSTRUCTOR: John Nicholson Meeting: Tuesday – Thursday, 2:20 – 3:35 pm. Instructor: John Nicholson Course Description The term Renaissance (literally “rebirth”) as used in art history designates the movement of renewal in the visual arts (painting, sculpture, and architecture) that originated in fourteenth century Florence and continued into the sixteenth century. This course deals with the first phase of the movement, the “early Renaissance” of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The study begins with the Italo-Byzantine and Gothic styles of the late Middle Ages and the new naturalistic style exemplified in the painting of Giotto and his followers in the fourteenth century. Florence held the dominant position in the fifteenth century (the quattrocento) with the innovations of Brunelleschi (architecture), Donatello (sculpture) and Masaccio (painting) followed by figures such as Fra Angelico, Leonbbattista Alberti, Piero della Francesca, Andrea del Pollaiuolo, Sandro Botticelli and others. The influence of Florentine art spread to northern Italy where artists such as Andrea Mantegna and Giovanni Bellini created their distinctive styles. The final section will deal with the transition to the High Renaissance in the art of Leonardo da Vinci and the early works of Michelangelo and Raphael. This study will be implemented through assigned readings, slide lectures, classroom discussion and a visit to Florence. Students will be advised and encouraged to visit churches, museums, and galleries during their travels in Italy and other European countries. Course Objectives The primary objective is to impart a knowledge and understanding of this very important period in the history of Italian and European art. -

Crean 1 from the Perfect Painting to the Late Quattrocento the Quattrocento in Italy Saw Many Various Artistic Styles. The

Crean 1 From the Perfect Painting to the Late Quattrocento The Quattrocento in Italy saw many various artistic styles. The fading of the Gothic style in the early Renaissance, to a more common approach first seen in the work of Masaccio, to the development of the perfect painting, and finally to the final artists of the Quattrocento, where naturalism dominated the stylistic choices of artists. Each new phase of style built upon the last as artists took old ideas and developed them in a constant effort of artistic innovation. The production of knowledge and questioning of reality drove the creation of new ideas and theories. By the later period of the Renaissance, art became the essence of Italy and its influence spread throughout Europe. The development of the perfect painting, also known as the second Renaissance style, came about in the early Quattrocento with artists such as Paolo Uccello, Domenico Veneziano, Andrea del Castagno and Leonbattista Alberti. The period of the perfect painter began as a result of the rapidly increasing writing and publication of artistic treatises. One of the first pieces of writing was by Alberti in 1435 titled Della Pittura and provided a general audience with surveys and advice regarding painting. The book expressed his opinions about the importance of geometry. Alberti’s writings also looked to “express the doctrine that ‘virtus’ was the most important quality to be sought in human life; [...] a combination of ideal human traits: intelligence, reason, knowledge, control, balance, perception, harmony, and dignity.” (H&W 239) As art historians we should also look at mid 16th century artist Giorgio Vasari and his latter literary work, The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (Lives for short) as a major artistic treatise.