National Gallery of Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Astronomical Garden of Venus and Mars-NG915: the Pivotal Role Of

The astronomical garden of Venus and Mars - NG915 : the pivotal role of Astronomy in dating and deciphering Botticelli’s masterpiece Mariateresa Crosta Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF- OATo), Via Osservatorio 20, Pino Torinese -10025, TO, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This essay demonstrates the key role of Astronomy in the Botticelli Venus and Mars-NG915 painting, to date only very partially understood. Worthwhile coin- cidences among the principles of the Ficinian philosophy, the historical characters involved and the compositional elements of the painting, show how the astronomi- cal knowledge of that time strongly influenced this masterpiece. First, Astronomy provides its precise dating since the artist used the astronomical ephemerides of his time, albeit preserving a mythological meaning, and a clue for Botticelli’s signature. Second, it allows the correlation among Botticelli’s creative intention, the historical facts and the astronomical phenomena such as the heliacal rising of the planet Venus in conjunction with the Aquarius constellation dating back to the earliest represen- tations of Venus in Mesopotamian culture. This work not only bears a significant value for the history of science and art, but, in the current era of three-dimensional mapping of billion stars about to be delivered by Gaia, states the role of astro- nomical heritage in Western culture. Finally, following the same method, a precise astronomical dating for the famous Primavera painting is suggested. Keywords: History of Astronomy, Science and Philosophy, Renaissance Art, Educa- tion. Introduction Since its acquisition by London’s National Gallery on June 1874, the painting Venus and Mars by Botticelli, cataloged as NG915, has remained a mystery to be interpreted [1]1. -

The Paintings and Sculpture Given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr

e. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE COLLECTIONS OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART \YASHINGTON The National Gallery will open to the public on March 18, 1941. For the first time, the Mellon Collection, deeded to the Nation in 1937, and the Kress Collection, given in 1939, will be shown. Both collections are devoted exclusively to painting and sculpture. The Mellon Collection covers the principal European schools from about the year 1200 to the early XIX Century, and includes also a number of early American portraits. The Kress Collection exhibits only Italian painting and sculpture and illustrates the complete development of the Italian schools from the early XIII Century in Florence, Siena, and Rome to the last creative moment in Venice at the end of the XVIII Century. V.'hile these two great collections will occupy a large number of galleries, ample space has been left for future development. Mr. Joseph E. Videner has recently announced that the Videner Collection is destined for the National Gallery and it is expected that other gifts will soon be added to the National Collection. Even at the present time, the collections in scope and quality will make the National Gallery one of the richest treasure houses of art in the wor 1 d. The paintings and sculpture given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr. Mellon have been acquired from some of -2- the most famous private collections abroad; the Dreyfus Collection in Paris, the Barberini Collection in Rome, the Benson Collection in London, the Giovanelli Collection in Venice, to mention only a few. -

Staff Working Paper No. 845 Eight Centuries of Global Real Interest Rates, R-G, and the ‘Suprasecular’ Decline, 1311–2018 Paul Schmelzing

CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 CODE OF PRACTICE 2007 -

Papers of the British School at Rome Some Drawings from the Antique

Papers of the British School at Rome http://journals.cambridge.org/ROM Additional services for Papers of the British School at Rome: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Some Drawings from the Antique attributed to Pisanello G. F. Hill Papers of the British School at Rome / Volume 3 / January 1906, pp 296 - 303 DOI: 10.1017/S0068246200005043, Published online: 09 August 2013 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0068246200005043 How to cite this article: G. F. Hill (1906). Some Drawings from the Antique attributed to Pisanello. Papers of the British School at Rome, 3, pp 296-303 doi:10.1017/S0068246200005043 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ROM, IP address: 128.233.210.97 on 12 Mar 2015 PAPERS OF THE BRITISH SCHOOL AT ROME VOL. III. No. 4 SOME DRAWINGS FROM THE ANTIQUE ATTRIBUTED TO PISANELLO BY G. F. HILL, M.A. LONDON: 1905 SOME DRAWINGS FROM THE ANTIQUE ATTRIBUTED TO PISANELLO. A CERTAIN number of the drawings ascribed to Pisanello, both in the Recueil Vallardi in the Louvre and elsewhere, are copies, more or less free, of antique originals.1 The doubts which have been expressed, by Courajod among others, as to the authenticity of some of these drawings are fully justified in the case of those which reproduce ancient coins. Thus we have, on fol. 12. no. 2266 v° of the Recueil Vallardi, a coin with the head of Augustus wearing a radiate crown, inscribed DIVVS AVGVSTVS PATER, and a head of young Heracles in a lion's skin, doubtless taken from a tetradrachm of Alexander the Great. -

Michelangelo Buonarotti

PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN PEOPLE MENTIONED IN WALDEN: MICHELANGELO BUONAROTTI 1475 March 6: The second of five brothers, Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born at Caprese, in Tuscany, to Francesca Neri and Ludovico di Leonardo di Buonarotto Simoni, who wrote: “Today March 6, 1475, a child of the male sex has been born to me and I have named him Michelangelo. He was born on Monday between 4 and 5 in the morning, at Caprese, where I am the Podestà.” His father’s family had for several generations been small-scale bankers in Firenzi but had in his father’s case failed to maintain its status. The father had only occasional government jobs and at the time of Michelangelo’s birth was administrator of this small dependent town. A few months later, however, the family would return to its permanent residence in Firenzi. Like his father Michelangelo would always consider himself to be a “son of Firenzi.” 1488 Michelangelo’s father, at this point a minor Florentine official with connections to the ruling Medici family, placed his son in the workshop of the painter Domenico Ghirlandaio. It was a step downward, to become a mere artist, a sort of artisan, and Michelangelo had been apprenticed only relatively late, the age of at 13. He was, however, being apprenticed to the city’s most prominent painter, for a three-year term. 1489 Allegedly with nothing more to learn from the painter to which he had been apprenticed in the previous year, Michelangelo went to study at the sculpture school in the Medici gardens and shortly thereafter was invited into the household of Lorenzo de’ Medici, the Magnificent. -

Observing Protest from a Place

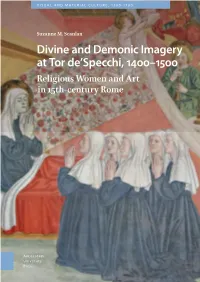

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Western Painting Renaissance I Eastern Europe / Western Europe

Introduction to Art Historical Research: Western Painting Renaissance I NTNU Graduate Institute of Art History September 23th 2009 ©2009 Dr Valentin Nussbaum, Associate Professor Eastern Europe / Western Europe •! Cult of images (icons) •! Culte of relics •! During the Middle Ages, images in Western Europe have a didactical purpose. They are pedagogical tools Conques, Abbatiale Sainte-Foy, Portail occidental, deuxième quart du 12ème s. 1 San Gimignano, view of the towers erected during the struggles between Ghelphs and Ghibellines factions (supporting respectively the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, ca. 1300 Bologne, The Asinelli and Garisenda Towers (height 98 metres) , 13th C. 2 Escorial. Codex T.I.1, fol. 50, Cantigas of Alfonso I, 13th C. Siena, Piazza del Campo with the Public Palace 3 Siena, (the Duomo (Cathedral and the Piazza del Campo with the Public Palace) Duccio di Buoninsegna, Polyptich No. 28, c. 1300-05, Tempera on wood 128 x 234 cm, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena 4 Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Altarpiece of St Proculus, 1332, 167 x 56 cm central panel and 145 x 43 cm each side panels, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child with Mary Magdalene and St Dorothea, c. 1325, (90 x 53 cm central panel 88 x 39 cm each side panels), Pinacoteca Nazionae, Siena 5 Duccio di Buoninsegna, Polyptich No. 28, c. 1300-05, Tempera on wood 128 x 234 cm, Pinacoteca Nazionae, Siena Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child with Mary Magdalene and St Dorothea, c. 1325, (90 x 53 cm central panel 88 x 39 cm each side panels), -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Old Master Paintings Master Old

Wednesday 29 April 2015 Wednesday Knightsbridge, London OLD MASTER PAINTINGS OLD MASTER PAINTINGS | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 29 April 2015 22274 OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 29 April 2015 at 13.00 Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS BIDS ENQUIRIES PRESS ENQUIRIES Montpelier Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 [email protected] [email protected] Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 8307 London SW7 1HH To bid via the internet please visit CUSTOMER SERVICES www.bonhams.com www.bonhams.com SPECIALISTS Monday to Friday 08.30 – 18.00 Andrew McKenzie +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 VIEWING TELEPHONE BIDDING +44 (0) 20 7468 8261 Sunday 26 April Bidding by telephone will only [email protected] Please see back of catalogue 11.00 – 15.00 be accepted on lots with a low for important notice to bidders Monday 27 April estimate in excess of £500. Caroline Oliphant 09.00 – 16.30 +44 (0) 20 7468 8271 ILLUSTRATIONS Tuesday 28 April Please note that bids should be [email protected] Front cover: Lot 84 (detail) 09.00 – 16.30 submitted no later than 4pm on Back cover: Lot 1 Wednesday 29 April the day prior to the sale. New Lisa Greaves 09.00 – 11.00 bidders must also provide proof +44 (0) 20 7468 8325 IMPORTANT INFORMATION of identity when submitting bids. [email protected] The United States Government SALE NUMBER Failure to do this may result in has banned the import of ivory 22274 your bid not being processed. Archie Parker into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 5877 ivory are indicated by the symbol CATALOGUE LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS [email protected] Ф printed beside the lot number £18 AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE in this catalogue. -

4 September Books

book reviews A sense of place The Mapping of North America by Philip D. Burden Raleigh Publications, 46 Talbot Road, Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire WD3 1HE, UK (US office: PO Box 16910, Stamford, Connecticut 06905): 1996. Pp. 568. $195, £120 Jared M. Diamond Today, no prudent motorist, sailor, pilot or hiker sets out into unfamiliar terrain without a printed map. We of the twentieth century take this dependence of travel on maps so completely for granted that we forget how recent it is. The first printed maps date only from the 1470s, a mere two decades after Gutenberg’s perfection of printing with movable type around 1455. Techniques of mapmaking evolved rapidly thereafter. So the most revolutionary change in the history of cartography coincides with the most revolutionary change in Europeans’ Abraham Ortelius’s classic map of the American continents published in Antwerp in 1570. knowledge of world geography, following Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the beliefs that California is an island, that north- no longer existed, having been destroyed by Americas in 1492. west America has a land connection to Siberia, European-born epidemic diseases spread The earliest sketch map of any part of the that a strait separates Central America from from contacts with de Soto and from Euro- Americas dates from 1492 or 1493; the earli- South America, and that the Amazon River pean visitors to the coast — diseases to which est preserved printed map of the Americas flows northwards rather than eastwards. Ini- Europeans had acquired genetic and from 1506. The succession of printed New tially less obvious, but even more important, immune resistance through a long history of World maps that followed is triply interest- is the book’s relevance to the fields of anthro- exposure, but to which Native Americans ing: it illustrates the development of carto- pology, biology, epidemiology and linguistics. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Domenico Ghirlandaio an Old Man and His Grandson (Ca 1480-1490)

COVER ART Domenico Ghirlandaio An Old Man and His Grandson (ca 1480-1490) HE IDENTITIES of the 2 figures in this paint- ing the existence of entire extended families. Married ing by Domenico Ghirlandaio are un- women were under pressure to repopulate the family and known, but the picture conveys such a community by being almost continuously pregnant, ex- close relationship between them that it has posing themselves repeatedly to the pain and serious risks long been assumed that they are grandfa- of childbirth. Mortality rates among infants and chil- Tther and grandson. Ghirlandaio was among the busiest dren were very high; historians estimate that about half and best-known painters in Florence in the late 15th cen- of all children died before they were ten years old. Un- tury—Michelangelo trained in his workshop—and this der these harsh conditions, families were especially pleased work was almost certainly commissioned by a wealthy to have a healthy boy who could continue the family name Florentine family of that era. and help sustain the family economically on reaching Art of the time was moving beyond strictly religious adulthood and for whom no dowry would be needed. But subject matter. This painting can be considered an early a healthy girl could also help with domestic chores and psychological portrait, with a bit of landscape included in raised the prospect of creating advantageous new links the window at the upper right. Its main theme seems to between families through marriage. be bonding across the generations. Ghirlandaio pro- So, what about the grandfather’s nose? Evidently, vides visual clues suggesting a comfortable intimacy he had a rhinophyma, a cosmetically disfiguring but oth- between the older man and the boy: their chests touch, erwise benign condition thought to be the end stage of the man’s embracing left arm is reciprocated by the rosacea, a common facial dermatosis.