View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rome: a Pilgrim’S Guide to the Eternal City James L

Rome: A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Eternal City James L. Papandrea, Ph.D. Checklist of Things to See at the Sites Capitoline Museums Building 1 Pieces of the Colossal Statue of Constantine Statue of Mars Bronze She-wolf with Twins Romulus and Remus Bernini’s Head of Medusa Statue of the Emperor Commodus dressed as Hercules Marcus Aurelius Equestrian Statue Statue of Hercules Foundation of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus In the Tunnel Grave Markers, Some with Christian Symbols Tabularium Balconies with View of the Forum Building 2 Hall of the Philosophers Hall of the Emperors National Museum @ Baths of Diocletian (Therme) Early Roman Empire Wall Paintings Roman Mosaic Floors Statue of Augustus as Pontifex Maximus (main floor atrium) Ancient Coins and Jewelry (in the basement) Vatican Museums Christian Sarcophagi (Early Christian Room) Painting of the Battle at the Milvian Bridge (Constantine Room) Painting of Pope Leo meeting Attila the Hun (Raphael Rooms) Raphael’s School of Athens (Raphael Rooms) The painting Fire in the Borgo, showing old St. Peter’s (Fire Room) Sistine Chapel San Clemente In the Current Church Seams in the schola cantorum Where it was Cut to Fit the Smaller Basilica The Bishop’s Chair is Made from the Tomb Marker of a Martyr Apse Mosaic with “Tree of Life” Cross In the Scavi Fourth Century Basilica with Ninth/Tenth Century Frescos Mithraeum Alleyway between Warehouse and Public Building/Roman House Santa Croce in Gerusalemme Find the Original Fourth Century Columns (look for the seams in the bases) Altar Tomb: St. Caesarius of Arles, Presider at the Council of Orange, 529 Titulus Crucis Brick, Found in 1492 In the St. -

Spolia's Implications in the Early Christian Church

BEYOND REUSE: SPOLIA’S IMPLICATIONS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCH by Larissa Grzesiak M.A., The University of British Columba, 2009 B.A. Hons., McMaster University, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate Studies (Art History) THE UNVERSIT Y OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) April 2011 © Larissa Grzesiak, 2011 Abstract When Vasari used the term spoglie to denote marbles taken from pagan monuments for Rome’s Christian churches, he related the Christians to barbarians, but noted their good taste in exotic, foreign marbles.1 Interest in spolia and colourful heterogeneity reflects a new aesthetic interest in variation that emerged in Late Antiquity, but a lack of contemporary sources make it difficult to discuss the motives behind spolia. Some scholars have attributed its use to practicality, stating that it was more expedient and economical, but this study aims to demonstrate that just as Scripture became more powerful through multiple layers of meaning, so too could spolia be understood as having many connotations for the viewer. I will focus on two major areas in which spolia could communicate meaning within the context of the Church: power dynamics, and teachings. I will first explore the clear ecumenical hierarchy and discourses of power that spolia delineated through its careful arrangement within the church, before turning to ideological implications for the Christian viewer. Focusing on the Lateran and St. Peter’s, this study examines the religious messages that can be found within the spoliated columns of early Christian churches. By examining biblical literature and patristic works, I will argue that these vast coloured columns communicated ideas surrounding Christian doctrine. -

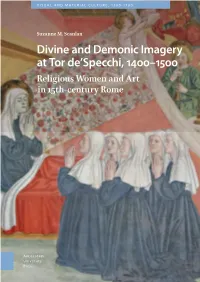

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Liturgy, Space, and Community in the Basilica Julii (Santa Maria in Trastevere)

DALE KINNEY Liturgy, Space, and Community in the Basilica Julii (Santa Maria in Trastevere) Abstract The Basilica Julii (also known as titulus Callisti and later as Santa Maria in Trastevere) provides a case study of the physical and social conditions in which early Christian liturgies ‘rewired’ their participants. This paper demon- strates that liturgical transformation was a two-way process, in which liturgy was the object as well as the agent of change. Three essential factors – the liturgy of the Eucharist, the space of the early Christian basilica, and the local Christian community – are described as they existed in Rome from the fourth through the ninth centuries. The essay then takes up the specific case of the Basilica Julii, showing how these three factors interacted in the con- crete conditions of a particular titular church. The basilica’s early Christian liturgical layout endured until the ninth century, when it was reconfigured by Pope Gregory IV (827-844) to bring the liturgical sub-spaces up-to- date. In Pope Gregory’s remodeling the original non-hierarchical layout was replaced by one in which celebrants were elevated above the congregation, women were segregated from men, and higher-ranking lay people were accorded places of honor distinct from those of lesser stature. These alterations brought the Basilica Julii in line with the requirements of the ninth-century papal stational liturgy. The stational liturgy was hierarchically orga- nized from the beginning, but distinctions became sharper in the course of the early Middle Ages in accordance with the expansion of papal authority and changes in lay society. -

Falda's Map As a Work Of

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art Sarah McPhee To cite this article: Sarah McPhee (2019) Falda’s Map as a Work of Art, The Art Bulletin, 101:2, 7-28, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2019.1527632 Published online: 20 May 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 79 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Falda’s Map as a Work of Art sarah mcphee In The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in the 1620s, the Oxford don Robert Burton remarks on the pleasure of maps: Methinks it would please any man to look upon a geographical map, . to behold, as it were, all the remote provinces, towns, cities of the world, and never to go forth of the limits of his study, to measure by the scale and compass their extent, distance, examine their site. .1 In the seventeenth century large and elaborate ornamental maps adorned the walls of country houses, princely galleries, and scholars’ studies. Burton’s words invoke the gallery of maps Pope Alexander VII assembled in Castel Gandolfo outside Rome in 1665 and animate Sutton Nicholls’s ink-and-wash drawing of Samuel Pepys’s library in London in 1693 (Fig. 1).2 There, in a room lined with bookcases and portraits, a map stands out, mounted on canvas and sus- pended from two cords; it is Giovanni Battista Falda’s view of Rome, published in 1676. -

The Well-Trained Theologian

THE WELL-TRAINED THEOLOGIAN essential texts for retrieving classical Christian theology part 1, patristic and medieval Matthew Barrett Credo 2020 Over the last several decades, evangelicalism’s lack of roots has become conspicuous. Many years ago, I experienced this firsthand as a university student and eventually as a seminary student. Books from the past were segregated to classes in church history, while classes on hermeneutics and biblical exegesis carried on as if no one had exegeted scripture prior to the Enlightenment. Sometimes systematics suffered from the same literary amnesia. When I first entered the PhD system, eager to continue my theological quest, I was given a long list of books to read just like every other student. Looking back, I now see what I could not see at the time: out of eight pages of bibliography, you could count on one hand the books that predated the modern era. I have taught at Christian colleges and seminaries on both sides of the Atlantic for a decade now and I can say, in all honesty, not much has changed. As students begin courses and prepare for seminars, as pastors are trained for the pulpit, they are not required to engage the wisdom of the ancient past firsthand or what many have labelled classical Christianity. Such chronological snobbery, as C. S. Lewis called it, is pervasive. The consequences of such a lopsided diet are now starting to unveil themselves. Recent controversy over the Trinity, for example, has manifested our ignorance of doctrines like eternal generation, a doctrine not only basic to biblical interpretation and Christian orthodoxy for almost two centuries, but a doctrine fundamental to the church’s Christian identity. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Seeds of the Reformation

Seeds of the Reformation Dr Nick Needham Church History | The Sword & Trowel 2017, issue 1 Seeds that blossomed into the Protestant Reformation of the 16th century – the various factors in the late medieval world that made the Reformation possible and pointed the way towards it – movements of thought and outstanding personalities. Some people like to see the Protestant Reformation as a celestial ‘bolt from the blue’, a miraculous restoration of apostolic Christianity which God (so to speak) dropped into history straight down from Heaven. That view once held sway in the English- speaking Protestant world. It was, however, strongly challenged in the middle of the 19th century by two reformed giants of historical-theological thinking, John Williamson Nevin and Philip Schaff of Mercersburg Seminary in Pennsylvania. Nevin was himself American, trained under Charles Hodge at Princeton, while Schaff was an English-speaker from Switzerland. I must admit my personal bias, and acknowledge that I have always been an admirer of the lives and work of Nevin and Schaff. (By the way, Schaff’s eight- volume History of the Christian Church is still a masterpiece worthy of our affection and attention. It combines depth of scholarship, flowing style, rich biographical colour, and spirituality of tone.) However, personal bias aside, the arguments of Nevin and Schaff won the day. The Reformation was no heavenly bolt from the blue. It grew organically out of the history that went before it. There were many historical roots that sprouted forth in the 16th century into the fruits of Reformation Protestantism. The historian can perceive and analyse those roots. -

“Allo Illustre, E Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De' Medici (...)”, Firenze

GIORGIO VASARI : “Allo Illustre, e Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De’ Medici (...)”, Firenze, 6 February 1568, fol. [2] r, in: VITA DEL GRAN MICHELAGNOLO BUONARROTI. Scritta da M. Giorgio Vasari, Scrttore & Architetto Aretino . Con le sue Magnifiche Essequie stategli fatte in Fiorenza. DALL ’ ACHADEMIA DEL DISEGNO (Florenz 1568). herausgegeben und kommentiert von CHARLES DAVIS FONTES 20 [19. Oktober 2008] Zitierfähige URL: http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/artdok/volltexte/2008/639 QUELLEN UND DOKUMENTE ZU MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI – E -TEXTE , NR. 2 SOURCES AND DOCUMENTS FOR MICHELANGELO BUONARROTI – E -TEXTS , NO. 2 GIORGIO VASARI , “Allo Illustre, e Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De’ Medici (...)”, Firenze, 6 February 1568 (Dedication), fol. [2] r, in: V I T A D E L GRAN MICHELAGNOLO BUONARROTI. Scritta da M. Giorgio Vasari, Pittore & Architetto Aretino . Con le sue Magnifiche Essequie stategli fatte in Fiorenza. DALL ’ ACHADEMIA DEL DISEGNO . Con Licenza, & Privilegio . I N F I O R E N Z A Nella Stamperia de’ Giunti 1568. FONTES 20 1 CONTENTS 3 THE TEXT 5 INTRODUCTION: VASARI , IL GRAN MICHELAGNOLO , AND ALESSANDRO DI OTTAVIANO DE ’ MEDICI 11 BIBLIOGRAPHY 12 THREE COMMENTARIES 14 OTTAVIANO DE ’ MEDICI 15 ALESSANDRO DI OTTAVIANO DE ’ MEDICI (L EONE XI) 16 “MICHELANGELO-BIBLIOGRAPHIE” 18 THE TEXT: English version 2 THE TEXT VITA DEL GRAN MICHELAGNOLO BUONARROTI. Scritta da M. Giorgio Vasari, Pittore & Architetto Aretino . Con le sue Magnifiche Essequie stategli fatte in Fiorenza. DALL ’ ACHADEMIA DEL DISEGNO . Con Licenza, & Privilegio . IN FIORENZA Nella Stamperia de’ Giunti 1568. fol. [2] r GIORGIO VASARI , “Allo Illustre, e Molto Magnifico M. Alessandro De’ Medici (...)”, Firenze, 6 February 1568 (Dedication), fol. -

A Revolution in Information?

A Revolution in Information? The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Blair, Ann, and Devin Fitzgerald. 2014. "A Revolution in Information?" In The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern European History, 1350-1750, edited by Hamish Scott, 244-65. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Published Version doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199597253.013.8 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:34334604 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Manuscript of Ann Blair and Devin Fitzgerald, "A Revolution in Information?" in the Oxford Handbook of Early Modern European History, ed. Hamish Scott (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), pp. 244-65. Chapter 10 A revolution in information?1 Ann Blair and Devin Fitzgerald The notion of a revolution in information in early modern Europe is a recent historiographical construct, inspired by the current use of the term to designate the transformations of the late 20th century. The notion, first propounded in the 1960s, that we live in an "information age" crucially defined by digital technologies for creating, storing, commoditizing, and disseminating information has motivated historians, especially since the late 1990s, to reflect on parallels with the past.2 Given the many definitions for "information" and related concepts, we will use the term in a nontechnical way, as distinct from data (which requires further processing before it can be meaningful) and from knowledge (which implies an individual knower). -

Rome of the Pilgrims and Pilgrimage to Rome

58 CHAPTER 2 Rome of the pilgrims and pilgrimage to Rome 2.1 Introduction As noted, the sacred topography of early Christian Rome focused on different sites: the official Constantinian foundations and the more private intra-mural churches, the tituli, often developed and enlarged under the patronage of wealthy Roman families or popes. A third, essential category is that of the extra- mural places of worship, almost always associated with catacombs or sites of martyrdom. It is these that will be examined here, with a particular attention paid to the documented interaction with Anglo-Saxon pilgrims, providing insight to their visual experience of Rome. The phenomenon of pilgrims and pilgrimage to Rome was caused and constantly influenced by the attitude of the early-Christian faithful and the Church hierarchies towards the cult of saints and martyrs. Rome became the focal point of this tendency for a number of reasons, not least of which was the actual presence of so many shrines of the Apostles and martyrs of the early Church. Also important was the architectural manipulation of these tombs, sepulchres and relics by the early popes: obviously and in the first place this was a direct consequence of the increasing number of pilgrims interested in visiting the sites, but it seems also to have been an act of intentional propaganda to focus attention on certain shrines, at least from the time of Pope Damasus (366-84).1 The topographic and architectonic centre of the mass of early Christian Rome kept shifting and moving, shaped by the needs of visitors and ‒ at the same time ‒ directing these same needs towards specific monuments; the monuments themselves were often built or renovated following a programme rich in liturgical and political sub-text. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1.