Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Framing the Painting: the Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[S]: Leonée Ormond Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5300/framing-the-painting-the-victorian-picture-sonnet-author-s-leon%C3%A9e-ormond-source-moveabletype-vol-5300.webp)

Framing the Painting: the Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[S]: Leonée Ormond Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Framing the Painting: The Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Author[s]: Leonée Ormond Source: MoveableType, Vol. 2, ‘The Mind’s Eye’ (2006) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.012 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2006 Leonée Ormond. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Framing the Painting: The Victorian “Picture Sonnet” Leonée Ormond During the Victorian period, the short poem which celebrates a single work of art became increasingly popular. Many, but not all, were sonnets, poems whose rectangular shape bears a satisfying similarity to that of a picture frame. The Italian or Petrarchan (rather than the Shakespearean) sonnet was the chosen form and many of the poems make dramatic use of the turn between the octet and sestet. I have chosen to restrict myself to sonnets or short poems which treat old master paintings, although there are numerous examples referring to contemporary art works. Some of these short “painter poems” are largely descriptive, evoking colour, design and structure through language. Others attempt to capture a more emotional or philosophical effect, concentrating on the response of the looker-on, usually the poet him or herself, or describing the emotion or inspiration of the painter or sculptor. Some of the most famous nineteenth century poems on the world of art, like Browning’s “Fra Lippo Lippi” or “Andrea del Sarto,” run to greater length. -

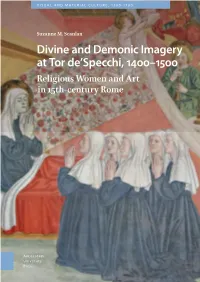

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Western Painting Renaissance I Eastern Europe / Western Europe

Introduction to Art Historical Research: Western Painting Renaissance I NTNU Graduate Institute of Art History September 23th 2009 ©2009 Dr Valentin Nussbaum, Associate Professor Eastern Europe / Western Europe •! Cult of images (icons) •! Culte of relics •! During the Middle Ages, images in Western Europe have a didactical purpose. They are pedagogical tools Conques, Abbatiale Sainte-Foy, Portail occidental, deuxième quart du 12ème s. 1 San Gimignano, view of the towers erected during the struggles between Ghelphs and Ghibellines factions (supporting respectively the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, ca. 1300 Bologne, The Asinelli and Garisenda Towers (height 98 metres) , 13th C. 2 Escorial. Codex T.I.1, fol. 50, Cantigas of Alfonso I, 13th C. Siena, Piazza del Campo with the Public Palace 3 Siena, (the Duomo (Cathedral and the Piazza del Campo with the Public Palace) Duccio di Buoninsegna, Polyptich No. 28, c. 1300-05, Tempera on wood 128 x 234 cm, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena 4 Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Altarpiece of St Proculus, 1332, 167 x 56 cm central panel and 145 x 43 cm each side panels, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child with Mary Magdalene and St Dorothea, c. 1325, (90 x 53 cm central panel 88 x 39 cm each side panels), Pinacoteca Nazionae, Siena 5 Duccio di Buoninsegna, Polyptich No. 28, c. 1300-05, Tempera on wood 128 x 234 cm, Pinacoteca Nazionae, Siena Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Madonna and Child with Mary Magdalene and St Dorothea, c. 1325, (90 x 53 cm central panel 88 x 39 cm each side panels), -

Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2002 Alberto Aringhieri and the Chapel of Saint John the Baptist: Patronage, Politics, and the Cult of Relics in Renaissance Siena Timothy B. Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE ALBERTO ARINGHIERI AND THE CHAPEL OF SAINT JOHN THE BAPTIST: PATRONAGE, POLITICS, AND THE CULT OF RELICS IN RENAISSANCE SIENA By TIMOTHY BRYAN SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2002 Copyright © 2002 Timothy Bryan Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Timothy Bryan Smith defended on November 1 2002. Jack Freiberg Professor Directing Dissertation Mark Pietralunga Outside Committee Member Nancy de Grummond Committee Member Robert Neuman Committee Member Approved: Paula Gerson, Chair, Department of Art History Sally McRorie, Dean, School of Visual Arts and Dance The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the abovenamed committee members. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I must thank the faculty and staff of the Department of Art History, Florida State University, for unfailing support from my first day in the doctoral program. In particular, two departmental chairs, Patricia Rose and Paula Gerson, always came to my aid when needed and helped facilitate the completion of the degree. I am especially indebted to those who have served on the dissertation committee: Nancy de Grummond, Robert Neuman, and Mark Pietralunga. -

Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00526-6 - The Italian Renaissance and Cultural Memory Patricia Emison Table of Contents More information CONTENTS List of Illustrations page viii Acknowledgments xi Note to the Reader xiii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 A HISTORIOGRAPHICAL OVERVIEW 9 3 NOT ONLY REBIRTH 27 4 TRUTH AND LIKENESS 62 5 VISUALIZING IDEAS 85 6 WHY DID THE HIGH RENAISSANCE HAPPEN? 133 7 REVOLUTIONARY NORMS OF BEAUTY 158 8 “GENIUS” 186 9 EPILOGUE 212 Bibliography 221 Index 225 vii © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00526-6 - The Italian Renaissance and Cultural Memory Patricia Emison Table of Contents More information LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS plates Color plates follow page xvi. I. Raphael, Entombment II. Giotto, Lamentation III. Raphael and Shop, Stufetta of Cardinal Bibbiena, Vatican Palace, Rome IV. Leonardo da Vinci, Mona Lisa V. Raphael, Baldassare Castiglione VI. Federico Barocci, Portrait of a Woman VII. Masaccio, left wall of the Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence, with Tribute Money above VIII. Raphael, Parnassus IX. Andrea Mantegna, ceiling of Camera degli Sposi, Ducal Palace, Mantua X. Pontormo, Deposition XI. Cima da Conegliano, St. John the Baptist with Sts. Peter, Mark, Jerome, and Paul XII. Michelangelo, Libyan Sibyl figures 1. Amico Aspertini, Meleager Being Carried page 12 2. Donatello, St. George (detail) 16 3. Ghiberti, St. Matthew 32 4. Nicola Pisano, Nativity 41 5. Giovanni Pisano, Hercules 42 6. Tempio Malatestiano, Rimini 48 7. Michelangelo, Tityus 53 8. Donatello, St. Mark 54 9. Donatello, Mary Magdalene 60 10. Donatello, David 60 11. -

THE BERNARD and MARY BERENSON COLLECTION of EUROPEAN PAINTINGS at I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls

THE BERNARD AND MARY BERENSON COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PAINTINGS AT I TATTI Carl Brandon Strehlke and Machtelt Brüggen Israëls GENERAL INDEX by Bonnie J. Blackburn Page numbers in italics indicate Albrighi, Luigi, 14, 34, 79, 143–44 Altichiero, 588 Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum catalogue entries. (Fig. 12.1) Alunno, Niccolò, 34, 59, 87–92, 618 Angelico (Fra), Virgin of Humility Alcanyiç, Miquel, and Starnina altarpiece for San Francesco, Cagli (no. SK-A-3011), 100 A Ascension (New York, (Milan, Brera, no. 504), 87, 91 Bellini, Giovanni, Virgin and Child Abbocatelli, Pentesilea di Guglielmo Metropolitan Museum altarpiece for San Nicolò, Foligno (nos. 3379 and A3287), 118 n. 4 degli, 574 of Art, no. 1876.10; New (Paris, Louvre, no. 53), 87 Bulgarini, Bartolomeo, Virgin of Abbott, Senda, 14, 43 nn. 17 and 41, 44 York, Hispanic Society of Annunciation for Confraternità Humility (no. A 4002), 193, 194 n. 60, 427, 674 n. 6 America, no. A2031), 527 dell’Annunziata, Perugia (Figs. 22.1, 22.2), 195–96 Abercorn, Duke of, 525 n. 3 Alessandro da Caravaggio, 203 (Perugia, Galleria Nazionale Cima da Conegliano (?), Virgin Aberdeen, Art Gallery Alesso di Benozzo and Gherardo dell’Umbria, no. 169), 92 and Child (no. SK–A 1219), Vecchietta, portable triptych del Fora Crucifixion (Claremont, Pomona 208 n. 14 (no. 4571), 607 Annunciation (App. 1), 536, 539 College Museum of Art, Giovanni di Paolo, Crucifixion Abraham, Bishop of Suzdal, 419 n. 2, 735 no. P 61.1.9), 92 n. 11 (no. SK-C-1596), 331 Accarigi family, 244 Alexander VI Borgia, Pope, 509, 576 Crucifixion (Foligno, Palazzo Gossaert, Jan, drawing of Hercules Acciaioli, Lorenzo, Bishop of Arezzo, Alexeivich, Alexei, Grand Duke of Arcivescovile), 90 Kills Eurythion (no. -

View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

PRESENT IN THE PERFORMANCE: STEFANO MADERNO’S SANTA CECILIA AND THE FRAME OF THE JUBILEE OF 1600 by KELLY ANNE WHITFORD A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kelly Anne Whitford Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Dr. James Harper Chairperson Dr. Nicola Camerlenghi Member Dr. Jessica Maier Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2011 ii © 2011 Kelly Anne Whitford iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kelly Anne Whitford Master of Arts Department of Art History December 2011 Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 In 1599, in commemoration of the remarkable discovery of the incorrupt remains of the early Christian martyr St. Cecilia, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrato commissioned Stefano Maderno to create a memorial sculpture which dramatically departed from earlier and contemporary monuments. While previous scholars have considered the influence of the historical setting on the conception of Maderno’s Santa Cecilia, none have studied how this historical moment affected the beholder of the work. In 1600, the Church’s Holy Year of Jubilee drew hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to Rome to take part in Church rites and rituals. -

AP Art History Chapter 21Questions: the Renaissance in Quattrocento Italy

AP Art History Chapter 21Questions: The Renaissance in Quattrocento Italy 1. _______ became a great patron of art and spent the equivalent of _____ dollars to establish the first public library since the ancient world. His grandson, _____ called the _______ spent lavishly on _______, ______, and sculptures. (559) 2. Of all the Florentine masters the Medici family employed, the most famous today is ______ ________. (559) 3. Botticelli painted _______ for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici. What is the narrative of this painting?(559) 4. What was humanism? What is meant by the “Renaissance man”? List at least three qualities of the Italian humanists.(560) 5. In 1401, there was a competition to make bronze doors for the Baptistery of San Giovanni. What was the subject matter for the panel and why was this chosen? Who were the two finalists? Who won and why? (560‐ 562) 6. In the Four Crowned Saints, how did the artist liberate the statuary from its architectural setting? (563) 7. Who is the artist of Saint Mark (figure 21‐5)? List at least three ways that he gives movement and frees it from its architectural setting. (564) 8. In Donatello’s, Saint George and the Dragon, how did he create atmospheric effect? 9. In Donatello’s, Feast of Herod, how does he create rationalized perspective space? 10. Read the grey insert on page 567. What is the definition of linear and atmospheric perspective? (565) 11. Why the east doors of the Baptistery of San Giovanni were called the “Gates of Paradise?” (566) 12. On the panels, the figures stand according to a ________‐_________ perspective and the figures almost appear fully in the _______. -

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects

Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Giorgio Vasari Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects Table of Contents Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors and Architects.......................................................................1 Giorgio Vasari..........................................................................................................................................2 LIFE OF FILIPPO LIPPI, CALLED FILIPPINO...................................................................................9 BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO........................................................................................................13 LIFE OF BERNARDINO PINTURICCHIO.........................................................................................14 FRANCESCO FRANCIA.....................................................................................................................17 LIFE OF FRANCESCO FRANCIA......................................................................................................18 PIETRO PERUGINO............................................................................................................................22 LIFE OF PIETRO PERUGINO.............................................................................................................23 VITTORE SCARPACCIA (CARPACCIO), AND OTHER VENETIAN AND LOMBARD PAINTERS...........................................................................................................................................31 -

Hercules: Flawed and Fixed

Hercules: Flawed and Fixed An Aristotelian Problem with a Kinesic Solution In Medici Florence Honors Thesis in the Department of Art History University of Oregon Cassidy Shaffer Spring 2019 The Medici family of Florence used Hercules as a dynastic symbol to project ideas of courage and strength onto the family. However, because Hercules is a deeply flawed character throughout the entirety of his story, the Medici needed to manipulate how people perceived the hero by commissioning sculpture that would reflect the desired moral values and courageous virtue. Florence was ruled by the Medici family for three centuries beginning with the return of Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici from exile in 1434.1 During these three centuries, the Medici family used the artistic innovation of the Florentine renaissance to profit politically. Beginning with Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici, large-scale Medici patronage of the arts continued steadily throughout the remainder of the 15th and 16th centuries within the family. Their commissions were often used to demonstrate the family’s wealth, status, religious beliefs, interests, and culture. They largely conveyed themes such as fortitude, piety, leadership, righteousness, and courage. Two of the most prominent figures used to present these concepts were the biblical David and the mythical Hercules. Adopted to the city’s seal in 12812, Hercules became a symbol of Florence and connected the city with these same virtues later indexed in Medici commissions. The Medici adopted the iconography of the hero Hercules as not only an expression of their family’s values, but also an articulation of what life in Florence would be like under Medici influence; through Hercules they projected themselves as quintessentially Florentine. -

ARTH206-Giorgio Vasari-Lives of the Most Emminent

Selections from Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors & Architects Giorgio Vasari, Translated by Gaston Du C. De Vere (1912-14) Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 1 of 199 LIVES OF THE MOST EMINENT PAINTERS SCULPTORS & ARCHITECTS 1912 BY GIORGIO VASARI: NEWLY TRANSLATED BY GASTON Du C. DE VERE. WITH FIVE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS: IN TEN VOLUMES LONDON: MACMILLAN AND CO. LD. & THE MEDICI SOCIETY, LD. 1912-14 CONTENTS Volume 1 3 Dedications to the Cosimo Medici 4 The Author’s Preface to the Whole Work 7 Giovanni Cimabue 19 Niccola and Giovanni of Pisa 31 Giotto 50 Ambrogio Lorenzetti 78 Volume 2 83 Duccio 84 Paolo Ucello 90 Lorenzo Ghiberti 100 Masolino Da Panicale 121 Masaccio 126 Filippo Brunelleschi 136 Donato [Donatello] 178 Volume 1 Footnotes 198 Volume 2 Footnotes 199 Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 2 of 199 VOLUME I Source URL: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25326/25326-h/25326-h.htm#Page_153 Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth206/ Saylor.org This work is in the public domain. Page 3 of 199 DEDICATIONS TO COSIMO DE' MEDICI TO THE MOST ILLUSTRIOUS AND MOST EXCELLENT SIGNOR COSIMO DE' MEDICI, DUKE OF FLORENCE AND SIENA MY MOST HONOURED LORD, Behold, seventeen years since I first presented to your most Illustrious Excellency the Lives, sketched so to speak, of the most famous painters, sculptors and architects, they come before you again, not indeed wholly finished, but so much changed from what they were and in such wise adorned and enriched with innumerable works, whereof up to that time I had been able to gain no further knowledge, that from my endeavour and in so far as in me lies nothing more can be looked for in them. -

METADATA and PHOTOGRAPHIC DOCUMENTATION Santa Maria Dell'assunzione – Ariccia, ITALY – by Bernini

TM ARCHIVISION www.archivision.com an image source for visual resource professionals Renseignements généraux en français disponibles sur demande. No part of this publication may be reproduced or printed, in whole or in part, without the written consent of Archivision. All terms and fees subject to change without notice. Archivision Inc. © 2009 Archivision Inc. All rights reserved. version April 2009 THE ARCHIVISION DIGITAL RESEARCH LIBRARY This catalogue is a partially illustrated content list of architectural sites, gardens, parks and works of art which comprise the Archivision Digital Research Library. The Archivision Library is currently 46,000 18 MB files and is composed of: 1) Base Collection (16,000 images) 2) Addition Module One (6,000 images) 3) Addition Module Two (6,000 images) 4) Addition Module Three (6,000 images) 4) Addition Module Four (6,000 images) 4) Addition Module Five (6,000 images) The content coverage within each Library module is: .: 60% architecture (most periods) .: 20% gardens & landscapes .: 15% public art .: 5% other design related topics The Archivision Library makes an ideal complement to any core art digital collection, such as the Saskia Archive or ARTstor. Only the Archivision Digital Research Library meets the needs of students and faculty – for both research and teaching – in the disciplines of architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning. We do not offer a subscription service – you must sign a site license agreement and pay a one-time license fee for the Library – then you may keep the images and related metadata in perpetuity with no additional annual fees. The exception is where you choose one of our hosted server options – the annual fee you pay is only for the access service.