Engaging Symbols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: a Historiographical Survey

chapter 11 The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: A Historiographical Survey Emanuela Ferretti* The Medici Palace has long been recognized as an architectural icon of the Florentine Quattrocento. This imposing building, commissioned by Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici (1389–1464), is a palimpsest that reveals complex layers rooted in the city’s architectural, urban, economic, and social history. A symbol – just like its patron – of a formidable era of Italian art, the palace on the Via Larga represents a key moment in the development of the palace type and and influenced every other Italian centre. Indeed, it is this building that scholars have identified as the prototype for the urban residence of the nobility.1 The aim of this chapter, based on a great wealth of secondary literature, including articles, essays, and monographs, is to touch upon several themes and problems of relevance to the Medici Palace, some of which remain unresolved or are still debated in the current scholarship. After delineating the basic construction chronology, this chapter will turn to questions such as the patron’s role in the building of his family palace, the architecture itself with regards to its spatial, morphological, and linguistic characteristics, and finally the issue of author- ship. We can try to draw the state of the literature: this preliminary historio- graphical survey comes more than twenty years after the monograph edited by Cherubini and Fanelli (1990)2 and follows an extensive period of innovative study of the Florentine early Quattrocento,3 as well as the fundamental works * I would like to thank Nadja Naksamija who checked the English translation, showing many kindnesses. -

Orsanmichele and the History and Preservation of the Civic Monument

Orsanmichele and the History and Preservation of the Civic Monument Edited by CARL BRANDON STREHLKE National Gallery of Art, Washington Distributed by Yale University Press New Haven and London Contents vii Preface ELIZABETH CROPPER ix Foreword CRISTINA ACI DI N I i Introduction CARL BRANDON STREHLKE 7 "Degno templo e tabernacol santo": Remembering and Renewing Orsanmichele DIANE FINIELLO ZERVAS 2i Orsanmichele before and after the Niche Sculptures: Making Decisions about Art in Renaissance Florence CARL BRANDON STREHLKE 3 5 Designing Orsanmichele: The Rediscovered Rule MARIA TERESA BARTOLI 53 Andrea Pisano's Saint Stephen and the Genesis of Monumental Sculpture at Orsanmichele ENRICA NERI LUSANNA 75 Giovanni di Balduccio at Orsanmichele: The Tabernacle of the Virgin before Andrea Orcagna FRANCESCO CAGLIOTI iii The Limestone Tracery in the Arches of the Original Grain Loggia of Orsanmichele in Florence GERT KREYTENBERG 125 The Trecento Sculptures in the Exterior Tabernacles at Orsanmichele ALESSANDRA GRIFFO 139 If Monuments Could Sing: Image, Song, and Civic Devotion inside Orsanmichele BLAKE WILSON 1 69 Orsanmichele: The Birthplace of Modern Sculpture ARTUR ROSENAUER 179 Restoration of the Statues in the Exterior Niches at Orsanmichele ANNAMARIA GIUSTI 187 The Fat Stonecarver MARY BERGSTEIN 197 Saint Peter of Orsanmichele LUCIANO BELLOSI 2 i 3 A More "Modern" Ghiberti: The Saint Matthew for Orsanmichele ELEONORA LUCIANO 243 Ghiberti's Saint Matthew and Roman Bronze Statuary: Technical Investigations during Restoration EDILBERTO FORMIGLI 257 Predella and Prontezza: On the Expression of Donatello's Saint George ARJAN R. DE KOOMEN 279 Scientific Investigations of the Bronze and Marble Statues of Orsanmichele MAURO MATTEINI 289 Words on an Image: Francesco da Sangallo's Sant'Anna Metterza for Orsanmichele COLIN EISLER WITH THE COLLABORATION OF ABBEY KORNFELD AND ALISON REBECCA W. -

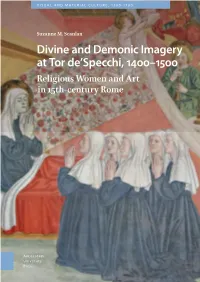

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Donatello's Terracotta Louvre Madonna

Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sandra E. Russell May 2015 © 2015 Sandra E. Russell. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning by SANDRA E. RUSSELL has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Professor of Art History Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract RUSSELL, SANDRA E., M.A., May 2015, Art History Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw A large relief at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (R.F. 353), is one of several examples of the Madonna and Child in terracotta now widely accepted as by Donatello (c. 1386-1466). A medium commonly used in antiquity, terracotta fell out of favor until the Quattrocento, when central Italian artists became reacquainted with it. Terracotta was cheap and versatile, and sculptors discovered that it was useful for a range of purposes, including modeling larger works, making life casts, and molding. Reliefs of the half- length image of the Madonna and Child became a particularly popular theme in terracotta, suitable for domestic use or installation in small chapels. Donatello’s Louvre Madonna presents this theme in a variation unusual in both its form and its approach. In order to better understand the structure and the meaning of this work, I undertook to make some clay works similar to or suggestive of it. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Tyler Farrell, Ph.D. Website: E-Mail: [email protected] Or [email protected]

Tyler Farrell, Ph.D. website: http://tylerfarrellpoetry.com/ e-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Educational Background 2002 Ph.D. in English (Creative Writing-Poetry, 20th C. American, British/Irish Poetry, Drama, Fiction) University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Dissertation: A Place Was Not Simply A Place – Poems Influenced by Ireland and the US 1997 M.A. in Literature, Creighton University, Omaha, Nebraska. Thesis: “From Miscommunication to Communion: Raymond Carver’s Progression from ‘The Bath’ to ‘A Small Good Thing.’ 1995 B.A. in English and Journalism (double major), Creighton University, Omaha, NE. Interests: Creative Writing (Poetry, Fiction, Non-Fiction, Drama, Screenwriting), Rhetoric & Composition, Drama and Poetry, 19th/20th Century British/Irish & American: Poetry, Fiction, Drama, Memoir. Film Studies. International Education. Professional Employment 2015-present Visiting Assistant Professor – Department of English– Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI 2010-2015 Lecturer – Department of English - Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI. 2009-2011 Lecturer – Department of English - Carroll University, Waukesha, WI. 2009 Instructor – Madison Area Technical College, Madison, WI. 2005-2008 Teaching Specialist/Asst. Prof.-Department of English-University of Dubuque, Dubuque, IA. 2003-2005 Visiting Assistant Professor-Department of English-Northland College, Ashland, WI 2002-2003 Lecturer, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Instructor, Madison Area Technical College 2000-2002 Teaching Assistant (Instructor), UW-Milwaukee -

Cellini Vs Michelangelo: a Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 22-30 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s).All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 Cellini vs Michelangelo: A Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia Maureen Maggio1 Abstract: Although a contemporary of the great Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini is not as well known to the general public today. Cellini, a master sculptor and goldsmith in his own right, made no secret of his admiration for Michelangelo’s work, and wrote treatises on artistic principles. In fact, Cellini’s artistic treatises can be argued to have exemplified the principles that Vasari and his contemporaries have attributed to Michelangelo. This paper provides an overview of the key Renaissance artistic principles of furia, forza, difficultà, terriblità, and fantasia, and uses them to examine and compare Cellini’s famous Perseus and Medusa in the Loggia deiLanzi to the work of Michelangelo, particularly his famous statue of David, displayed in the Galleria dell’ Accademia. Using these principles, this analysis shows that Cellini not only knew of the artistic principles of Michelangelo, but that his work also displays a mastery of these principles equal to Michelangelo’s masterpieces. Keywords: Cellini, Michelangelo, Renaissance aesthetics, Renaissance Sculptors, Italian Renaissance 1.0Introduction Benvenuto Cellini was a Florentine master sculptor and goldsmith who was a contemporary of the great Michelangelo (Fenton, 2010). Cellini had been educated at the Accademiade lDisegno where Michelangelo’s artistic principles were being taught (Jack, 1976). -

Lorenzo De Medici a Brief Biography Medici-A-Brief-Biography.Html by Robbi Erickson July 21, 2005

Lorenzo de Medici a Brief Biography http://www.googobits.com/articles/p0-1594-lorenzo-de- medici-a-brief-biography.html by Robbi Erickson July 21, 2005 Lorenzo de Medici was the grandson of Cosimo de Medici, and he took the reigns of control over Florence from Cosimo in 1469. (Rabb and Marshall, 1993, p. 28). While Cosimo had taken a low profile approach to governing Florence, Lorenzo was not afraid of confrontation, and he took a more prominent position in Florence society. Shortly after his inheritance of his grandfather’s position, his father also passed and left him with a sizable fortune. Newly married to Clarice Orsini, Lorenzo had the support of two powerful families behind him. (Durant, 1953, pp. 110-111). Young and inexperienced in bureaucracy, this transition in power could have been the perfect time for another power source to take over the city. However this was not the case, as his family, friends, debtors, and associates of the Medici were so numerous, that the young man had plenty of support and guidance in his rule. He was still highly criticized for being young, so Lorenzo hired the best minds in the area to act as 1 political and financial councilors to him. (Durant, 1953, p. 111). While Lorenzo maintained this council throughout his career, he soon developed his own good judgement that their input was not needed very often. In 1471 Lorenzo renewed the Medici’s connection to the Papacy, and was granted management rights over the Papacy finances once again. However, upon his return to Florence Lorenzo’s success in Rome was met with his first major crisis of his rule. -

Ascanio Condivi (1525-1574) Discepolo E Biografo Di Michelangelo Buonarroti

DIPARTIMENTO DI STORIA DELL’ARTE E SPETTACOLO DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN Strumenti e Metodi per la Storia dell’Arte Coordinatore: Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Silvia DANESI SQUARZINA Ascanio Condivi (1525-1574) discepolo e biografo di Michelangelo Buonarroti Tomo I TUTOR: DOTTORANDA: Chiar.ma Prof.ssa Dott.ssa Beniamina MAZZUCA Silvia DANESI SQUARZINA XXIV Ciclo (aa.aa. 2008-2011) A mio padre Un ringraziamento sentito rivolgo alla prof.ssa Silvia Danesi Squarzina, insostituibile guida nel lavoro di questi anni, segnati dai suoi preziosi insegnamenti. Un vivo grazie anche alla prof.ssa Costanza Barbieri per il sostegno, la disponibilità e la grande cortesia riservatemi. Con affetto e simpatia ringrazio Luca Calenne e Tiziana Checchi, che mi hanno aiutata nella trascrizione dei documenti, e tutti gli amici e colleghi, in particolare Laura, Francesca e Carlo. Alla mia famiglia, a Valentino e ai miei amici di sempre: grazie di tutto. Indice TOMO I Introduzione VIII 1. Ascanio Condivi (1525-1574) 1.1. Lo stato degli studi 1 1.2. Origini della famiglia Condivi 8 1.3. Nascita e formazione 9 1.4. Primo viaggio a Roma 10 1.5. Un caso di omonimia 12 1.6. Il soggiorno romano 14 1.7. Ritorno a Ripatransone: le nozze e il turbolento rapporto con Annibal Caro 17 1.8. L’elezione tra i membri dell’Accademia Fiorentina 22 1.9. Gli ultimi anni a Ripatransone e la morte 24 1.10. Le opere di Ascanio Condivi nei documenti dell’archivio storico di Ripatransone 27 1.11. La discendenza 31 1.12. I ritratti di Ascanio Condivi e dei suoi discendenti 33 2. -

Lecture 20 Italian Renaissance WC 373-383 PP 405-9: Machiavelli, Prince Chronology 1434 1440 1498 1504 1511 1512 1513 Medici

Lecture 20 Italian Renaissance WC 373-383 PP 405-9: Machiavelli, Prince Chronology 1434 Medici Family runs Florence 1440 Lorenzo Medici debunks “Donation of Constantine” 1498 da Vinci, The Last Supper created 1504 Michelangelo completes statue of David 1511 Rafael, The School of Athens created 1512 Michelangelo completes Sistine Chapel 1513 Machiavelli writes The Prince Star Terms Geog. Terms Renaissance Republic of Florence Medici Republic of Siena florin Papal States perspective Bolonia realism Milan A. Botticelli, Birth of Venus (1486) currently in the Uffizi, Florence The Birth of Venus is probably Botticelli's most famous painting and was commissioned by the Medici family. Venus rises from the sea, looking like a classical statue and floating on a seashell. On Venus' right is Zephyrus, God of Winds, he carries with him the gentle breeze Aura and together they blow the Goddess of Love ashore. The Horae, Goddess of the Seasons, waits to receive Venus and spreads out a flower covered robe in readiness for the Love Goddess' arrival. In what is surely one of the most recognizable images in art history, this image is significant because it attests to the revival of Greco-Roman forms to European art and gives form to the idea behind the Renaissance: a rebirth by using Classical knowledge. Lecture 20 Italian Renaissance B. Florence Cathedral (the Duomo) Florence Italy (1436) The Duomo, the main church of Florence, Italy had begun in 1296 in the Gothic style to the design of Arnolfo di Cambio and completed structurally in 1436 with the dome engineered by Filippo Brunelleschi, who won the competition for its commission in 1418. -

Download February 2021

ALWAYS Mendocino Coast's FREE Lighthouse February 2021 Peddler The Best Original Writing, plus the Guide to Art, Music, Events, Theater, Film, Books, Poetry and Life on the Coast ValentinesValentines DayDay ArtArt toto Enjoy,Enjoy, 22 GalleriesGalleries toto VisitVisit We’re blessed here on the coast with a world of art that surrounds us. We can take a look at the art, spend a li!le time gazing upon it, read something into it or just enjoy the moment. "is month two of our local galleries will have new exhibits and both are worth a look. So we’ve planned a day for you. Start your day in Gualala at the Dolphin Gallery for their new opening “Hearts for the Arts. "en take an easy 15 minute drive north to Point Arena for a stop at the Coast Highway art Collective where members of the collective will present Valentines Art. And don’t forget to look at the ocean as you drive between the two galleries. Both galleries will welcome you, and you will be assured a delightful day. At the Dolphin Gallery the new exhibit, “Hearts for the Arts”, brings together three artists: Jane Head’s focus on clay, Walt Rush’s on jewels, and Leslie Moody Cresswell’s glass. Cont'd on Page 12 Coast Highway Art Collective in February • Valentines Art and Poetry Meet February 6 By Rozann Grunig !e members of the Coast Highway Art mechanically adept artist mother” and her Council to deliver creative arts instruction Collective are hosting their "rst opening “gregarious, disordered, audacious poet fa- in K-12 classrooms around the Northern reception of 2021 on Saturday, February 6 ther,” she says. -

Tuscany's World Heritage Sites

15 MARCH 2013 CATERINA POMINI 4171 TUSCANY'S WORLD HERITAGE SITES As of 2011, Italy has 47 sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, making it the country with the greatest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Tuscany alone boasts six UNESCO sites, almost equalling the numbers of countries like Croatia, Finland and Norway. Tuscany enshrines 6 Unesco World Heritage Sites you should definitely consider when planning your Tuscany tour. Here is the list: 1) Florence. Everything that could be said about the historic centre of Florence has already been said. Art, history, territory, atmosphere, traditions, everybody loves this city depicted by many as the Cradle of the Renaissance. Florence attracts millions of tourists every year and has been declared a World Heritage Site due to the fact that it represents a masterpiece of human creative genius + other 4 selection criteria. 2) Piazza dei Miracoli, Pisa. It was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1987 and is basically a wide walled area, partially paved and partially covered by grass, dominated by 4 great religious buildings: the Duomo, the Leaning Tower, the Baptistry and the Camposanto. 3) San Gimignano has been a World Heritage Site since 1990 and is considered the emblem of medieval Tuscany. Its historic centre represents a masterpiece of human creative genius, it bears a unique testimony to Tuscan civilization and surely is an outstanding example of architectural ensemble, which illustrates significant stages in human history. 4) 40 kilometers away from San Gimignano stands Siena, the historical enemy of Florence. Throughout the centuries, the city's medieval appearance has been preserved and expansion took place outside the walls.