Hercules: Flawed and Fixed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livy's View of the Roman National Character

James Luce, December 5th, 1993 Livy's View of the Roman National Character As early as 1663, Francis Pope named his plantation, in what would later become Washington, DC, "Rome" and renamed Goose Creek "Tiber", a local hill "Capitolium", an example of the way in which the colonists would draw upon ancient Rome for names, architecture and ideas. The founding fathers often called America "the New Rome", a place where, as Charles Lee said to Patrick Henry, Roman republican ideals were being realized. The Roman historian Livy (Titus Livius, 59 BC-AD 17) lived at the juncture of the breakdown of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire. His 142 book History of Rome from 753 to 9 BC (35 books now extant, the rest epitomes) was one of the most read Latin authors by early American colonists, partly because he wrote about the Roman national character and his unique view of how that character was formed. "National character" is no longer considered a valid term, nations may not really have specific national characters, but many think they do. The ancients believed states or peoples had a national character and that it arose one of 3 ways: 1) innate/racial: Aristotle believed that all non-Greeks were barbarous and suited to be slaves; Romans believed that Carthaginians were perfidious. 2) influence of geography/climate: e.g., that Northern tribes were vigorous but dumb 3) influence of institutions and national norms based on political and family life. The Greek historian Polybios believed that Roman institutions (e.g., division of government into senate, assemblies and magistrates, each with its own powers) made the Romans great, and the architects of the American constitution read this with especial care and interest. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

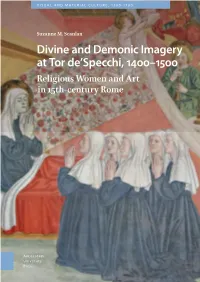

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 112 438 CS 202 298 AUTHOR Smith, Ron TITLE A Guide to Post-Classical Works of Art, Literature, and Music Based on Myths of the Greeks and Romans. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 40p.; Prepared at Utah State University; Not available in hard copy due to marginal legibility of original document !DRS PRICE MF-$0.76 Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Art; *Bibliographies; Greek Literature; Higher Education; Latin Literature; *Literature; Literature Guides; *Music; *Mythology ABSTRACT The approximately 650 works listed in this guide have as their focus the myths cf the Greeks and Romans. Titles were chosen as being (1)interesting treatments of the subject matter, (2) representative of a variety of types, styles, and time periods, and (3) available in some way. Entries are listed in one of four categories - -art, literature, music, and bibliography of secondary sources--and an introduction to the guide provides information on the use and organization of the guide.(JM) *********************************************************************** Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * * of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). EDRS is not * responsible for the quality of the original document. Reproductions * * supplied -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

THE HERO and HIS MOTHERS in SENECA's Hercules Furens

SYMBOLAE PHILOLOGORUM POSNANIENSIUM GRAECAE ET LATINAE XXIII/1 • 2013 pp. 103–128. ISBN 978-83-7654-209-6. ISSN 0302-7384 Mateusz Stróżyński Instytut Filologii Klasycznej Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza ul. Fredry 10, 61-701 Poznań Polska – Poland The Hero and His Mothers in Seneca’S Hercules FUreNs abstraCt. Stróżyński Mateusz, The hero and his mothers in Seneca’s Hercules Furens. The article deals with an image of the heroic self in Seneca’s Hercules as well as with maternal images (Alcmena, Juno and Megara), using psychoanalytic methodology involving identification of complementary self-object relationships. Hercules’ self seems to be construed mainly in an omnipotent, narcissistic fashion, whereas the three images of mothers reflect show the interaction between love and aggression in the play. Keywords: Seneca, Hercules, mother, psychoanalysis. Introduction Recently, Thalia Papadopoulou have observed that the critics writing about Seneca’s Hercules Furens are divided into two groups and that the division is quite similar to what can be seen in the scholarly reactions to Euripides’ Her- akles.1 However, the reader of Hercules Furens probably will not find much 1 See: T. Papadopoulou, Herakles and Hercules: The Hero’s ambivalence in euripides and seneca, “Mnemosyne” 57:3, 2004, pp. 257–283. The author reviews shortly the literature about the play and in the first group of critics, of those who are convinced that Hercules is “mad” from the beginning, but his madness gradually develops, she enumerates Galinsky (G.K. Galinsky, The Herakles Theme: The adaptations of the Hero in literature from Homer to the Twentieth Century, Oxford 1972), Zintzen (C. -

The Hercules Story Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE HERCULES STORY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin W. Bowman | 128 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752450810 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom The Hercules Story PDF Book More From the Los Angeles Times. The god Apollo. Then she tried to kill the baby by sending snakes into his crib. Hercules was incredibly strong, even as a baby! When the tasks were completed, Apollo said, Hercules would become immortal. Deianira had a magic balm which a centaur had given to her. July 23, Hercules was able to drive the fearful boar into snow where he captured the boar in a net and brought the boar to Eurystheus. Greek Nyx: The Goddess of the Night. Eurystheus ordered Hercules to bring him the wild boar from the mountain of Erymanthos. Like many Greek gods, Poseidon was worshiped under many names that give insight into his importance Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. Athena observed Heracles shrewdness and bravery and thus became an ally for life. The name Herakles means "glorious gift of Hera" in Greek, and that got Hera angrier still. Feb 14, Alexandra Dantzer. History at Home. Hercules was born a demi-god. On Wednesday afternoon, Sorbo retweeted a photo of some of the people who swarmed the U. Hercules could barely hear her, her whisper was that soft, yet somehow, and just as the Oracle had predicted to herself, Hera's spies discovered what the Oracle had told him. As he grew and his strength increased, Hera was evermore furious. -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry. -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

Echi Classici Nell'opera Di Seamus Heaney

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI PARMA Dottorato di ricerca in Filologia Greca e Latina (e fortuna dei classici) Ciclo XXVIII L’Orfeo d’Irlanda: echi classici nell’opera di Seamus Heaney Coordinatore: Chiar.mo Prof. Giuseppe Gilberto Biondi Tutor: Chiar.ma Prof. ssa Mariella Bonvicini Dottoranda: Lidia Sessi Indice Introduzione p. 2 Capitolo I: La tradizione classica in Irlanda p. 7 Capitolo II: In difesa della poesia p. 56 Capitolo III: L'Orestea d'Irlanda p. 97 Capitolo IV: Il rito della sepoltura tra Grecia classica e Irlanda moderna p. 146 Capitolo V: Vergilius redivivus p. 190 Appendice p. 253 1 Introduzione In considerazione del notevole numero di studi sull'opera di Heaney, pare opportuno che ogni nuovo lavoro dichiari la propria raison d'être. In altre parole, sembra necessario precisare quale contributo si presuma di offrire alla comprensione del percorso poetico di Heaney, anche in rapporto alle monografie e ai saggi esistenti. È il poeta stesso a indicare la chiave di lettura che meglio consente di cogliere il senso profondo della sua ricerca estetica ed etica. Nel componimento “Out of the Bag” il narratore richiama l'attenzione su “the cure / By poetry that cannot be coerced”1. Riassumendo in questo verso le qualità fondamentali dell'arte poetica, Heaney mette in luce i tratti distintivi della sua produzione, sempre alla ricerca, fin dalle prime prestazioni, di una mediazione fra le pressioni socio-politiche del mondo esterno e la volontà di mantenere intatto il potere terapeutico del medium poetico. Lo scopo di questa ricerca è quello di affrontare la lettura, o rilettura, delle poesie di Heaney, come egli stesso suggerisce in “Squarings XXXVII”: “Talking about it isn't good enough / But quoting from it at least demonstrates / The virtue of an art that knows its mind”2. -

View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

PRESENT IN THE PERFORMANCE: STEFANO MADERNO’S SANTA CECILIA AND THE FRAME OF THE JUBILEE OF 1600 by KELLY ANNE WHITFORD A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kelly Anne Whitford Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Dr. James Harper Chairperson Dr. Nicola Camerlenghi Member Dr. Jessica Maier Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2011 ii © 2011 Kelly Anne Whitford iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kelly Anne Whitford Master of Arts Department of Art History December 2011 Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 In 1599, in commemoration of the remarkable discovery of the incorrupt remains of the early Christian martyr St. Cecilia, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrato commissioned Stefano Maderno to create a memorial sculpture which dramatically departed from earlier and contemporary monuments. While previous scholars have considered the influence of the historical setting on the conception of Maderno’s Santa Cecilia, none have studied how this historical moment affected the beholder of the work. In 1600, the Church’s Holy Year of Jubilee drew hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to Rome to take part in Church rites and rituals. -

THE HERCULES-CACUS MYTH As Buchheit Notes, It Would Be a Mistake to Take So Carefully Elaborated an Episode As the Hercules-Cacu

CHAPTER THREE THE HERCULES-CACUS MYTH As Buchheit notes, it would be a mistake to take so carefully elaborated an episode as the Hercules-Cacus battle as simply an aetiology. That author goes on to make an appealing case for consideration of the episode as symbolic of the coming struggle between Aeneas and Turnus,l and doing so he shares the approach of Schnepf, whose main conclusion is that Hercules is a symbol, but of Augustus. 2 I t is not our principal purpose here to consider whether or not the symbolic interpretations of Buchheit and others are valid. We are basically investigating the likenesses and contrasts of form between Vergil and Callimachus, and hoping to demonstrate that such an investigation, differing widely as it does from those of Schnepf and Buchheit, still yields significant information concerning the art of Vergil. Before beginning we should note that the aitia of Aen. 8, bearing clearly as they do upon institutions, etc., of Vergil's day, betray a contemporary urgency undiscovered in the A itia of Callimachus. In this respect they justify the effort expended to elucidate the Augustan significance of the Hercules-Cacus myth. Attempts to find symbolic or allegorical dimensions of the myth which relate it to Augustus, even if carried too far at times,3 are neverthe less reasonable in principle. At any rate, this study shares with others a search for contemporary Augustan meaning in the Her cules-aition, as this chapter will show. Earlier literature on the passage disclosed much a bout the material at Vergil's disposal and its use by various writers; 4 1 Virgil uber die Sendung Roms, Gymnasium Beiheft 3 (Heidelberg, 1963) pp.