ARTH206-Giorgio Vasari-Lives of the Most Emminent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

Stepping out of Brunelleschi's Shadow

STEPPING OUT OF BRUNELLESCHI’S SHADOW. THE CONSECRATION OF SANTA MARIA DEL FIORE AS INTERNATIONAL STATECRAFT IN MEDICEAN FLORENCE Roger J. Crum In his De pictura of 1435 (translated by the author into Italian as Della pittura in 1436) Leon Battista Alberti praised Brunelleschi’s dome of Florence cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore [Fig. 1], as ‘such a large struc- ture’ that it rose ‘above the skies, ample to cover with its shadow all the Tuscan people’.1 Alberti was writing metaphorically, but he might as easily have written literally in prediction of the shadowing effect that Brunelleschi’s dome, dedicated on 30 August 1436, would eventually cast over the Florentine cultural and historical landscape of the next several centuries.2 So ever-present has Brunelleschi’s structure been in the historical perspective of scholars – not to mention in the more popular conception of Florence – that its stately coming into being in the Quattrocento has almost fully overshadowed in memory and sense of importance another significant moment in the history of the cathedral and city of Florence that immediately preceded the dome’s dedication in 1436: the consecration of Santa Maria del Fiore itself on 25 March of that same year.3 The cathedral was consecrated by Pope Eugenius IV (r. 1431–1447), and the ceremony witnessed the unification in purpose of high eccle- siastical, foreign, and Florentine dignitaries. The event brought to a close a history that had begun 140 years earlier when the first stones of the church were laid in 1296; in 1436, the actual date of the con- secration was particularly auspicious, for not only is 25 March the feast of the Annunciation, but in the Renaissance that day was also the start of the Florentine calendar year. -

The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: a Historiographical Survey

chapter 11 The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: A Historiographical Survey Emanuela Ferretti* The Medici Palace has long been recognized as an architectural icon of the Florentine Quattrocento. This imposing building, commissioned by Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici (1389–1464), is a palimpsest that reveals complex layers rooted in the city’s architectural, urban, economic, and social history. A symbol – just like its patron – of a formidable era of Italian art, the palace on the Via Larga represents a key moment in the development of the palace type and and influenced every other Italian centre. Indeed, it is this building that scholars have identified as the prototype for the urban residence of the nobility.1 The aim of this chapter, based on a great wealth of secondary literature, including articles, essays, and monographs, is to touch upon several themes and problems of relevance to the Medici Palace, some of which remain unresolved or are still debated in the current scholarship. After delineating the basic construction chronology, this chapter will turn to questions such as the patron’s role in the building of his family palace, the architecture itself with regards to its spatial, morphological, and linguistic characteristics, and finally the issue of author- ship. We can try to draw the state of the literature: this preliminary historio- graphical survey comes more than twenty years after the monograph edited by Cherubini and Fanelli (1990)2 and follows an extensive period of innovative study of the Florentine early Quattrocento,3 as well as the fundamental works * I would like to thank Nadja Naksamija who checked the English translation, showing many kindnesses. -

Vol 3 Issue 2 Artistic Impression

Vol. 3, Issue 2 February, 2021 Burlington Artists League A Word from the President Dear BAL members, Welcome to the February edition of our newsletter. Our previous editor has resigned and until we can find another one, Angela Bostek is serving as our interim editor, taking on yet another responsibility. Our profound thanks, Angela. The month of February conjures up associations with the bleak mid-winter season. On the other hand, it anticipates the arrival of spring, especially if the ground-hog’s prognostications are correct. For us, it means the Small Art Contest. I am pleased that the contest this year has been a success. The entries were as fine as ever and my thanks to all participants and congratulations to the winners! Unfortunately, due to Covid restrictions, we could not have our usual reception to honor the winners. However, as usual, all entries will be on display for the month of February. Please take an hour or so during the month to drop by the gallery to admire all the art submitted for the contest. It’s quite impressive. Now we look forward to the next competition in April. Further information will be forthcoming, watch your email. We hope you will join us for our monthly business meeting by way of Zoom on Thursday, February 18, at 3 p.m. One of the main agenda items will be a discussion of possibly adding a competition at the end of the summer and your input is valuable. In the meantime, stay warm and safe. Jane ********* FEBRUARY CALENDAR OF EVENTS 1st – 28th 14th 18th Jan 22 – Feb 18 Feb. -

Observing Protest from a Place

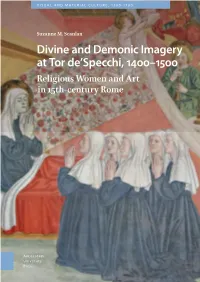

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Donatello's Terracotta Louvre Madonna

Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sandra E. Russell May 2015 © 2015 Sandra E. Russell. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning by SANDRA E. RUSSELL has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Professor of Art History Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract RUSSELL, SANDRA E., M.A., May 2015, Art History Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw A large relief at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (R.F. 353), is one of several examples of the Madonna and Child in terracotta now widely accepted as by Donatello (c. 1386-1466). A medium commonly used in antiquity, terracotta fell out of favor until the Quattrocento, when central Italian artists became reacquainted with it. Terracotta was cheap and versatile, and sculptors discovered that it was useful for a range of purposes, including modeling larger works, making life casts, and molding. Reliefs of the half- length image of the Madonna and Child became a particularly popular theme in terracotta, suitable for domestic use or installation in small chapels. Donatello’s Louvre Madonna presents this theme in a variation unusual in both its form and its approach. In order to better understand the structure and the meaning of this work, I undertook to make some clay works similar to or suggestive of it. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Street Culture Italia

1 Students and Faculty in Pompeii inside cover 2 3 Rome PHOTO // Tanesha Hobson image image 4 5 Venice PHOTO // Marco Sarno CONTENTSPreface 8 Flight Map 12 Art 14 Architecture 32 Religion 50 Culture 68 Program Faculty 86 Tour Guides 88 Itinerary 92 Acknowledgements 94 6 The Fourm, Rome 7 PHOTO // Jessica Demaio The Arts of Italy’s greatest success was in introducing William PREFACE Paterson’s art students to not By Professor Claudia Goldstein only the art and culture of Italy, but to the possibility and joy of international travel. THE ARTS OF ITALY, A TWO WEEK WINTER SESSION COURSE encounters with the towering Palazzo Vecchio and the view — at the top of We then traveled to Rome, the Eternal City, where we immersed WHICH TOOK TWELVE STUDENTS TO SIX CITIES IN ITALY OVER many, many steps — from the medieval church of San Miniato al Monte. ourselves in more than two thousand years of history. We got a fascinating WINTER BREAK 2016-17, WAS CONCEIVED AS AN IDEA — AND TO After we caught our breath, we also caught a beautiful Florentine sunset tour of the Roman Forum from an American architectural historian and SOME EXTENT A PIPE DREAM — ALMOST A DECADE AGO. which illuminated the Cathedral complex, the Palazzo Vecchio, and the architect who has lived in Rome for 25 years, and an expert on Jesuit The dream was to take a group of students on a journey across Italy to show surrounding city and countryside. architecture led us through the Baroque churches of Sant’Ignazio and Il them some of that country’s vast amount of art and architectural history, We spent three beautiful days in Florence — arguably the students’ Gesu’. -

Andrea Di Bonaiuto, Thomas Aquinas, and the Unity Of

http://www.amatterofmind.us/ PIERRE BEAUDRY’S GALACTIC PARKING LOT ANDREA DI BONAIUTO, THOMAS AQUINAS, AND THE UNITY OF OPPOSITES An epistemological experiment of axiomatic change in artistic composition. By Pierre Beaudry, 7/23/17 INTRODUCTION The difference between Raphael de Sanzio and Andrea di Bonaiuto in their artistic treatments of the fundamental differences between Plato and Aristotle is a matter of great importance for the epistemology of axiomatics, because it is timeless. Raphael explicitly represented the two philosophers in his painting, The School of Athens, as two opposite figures, one pointing upward to the domain of ideas and the other pointing downward to the domain of the senses. Almost a hundred and fifty years before, Andrea di Bonaiuto painted three frescos representing the same difference through a process of axiomatic transformation from one to the other in his masterful composition in the Spanish Chapel, in Florence. Imagine yourself entering the Spanish Chapel of Santa Maria Novella in Florence with one idea in mind: experiment the axiomatic change that Andrea di Bonaiuto has set the stage for you in three immense frescos. As you enter, your head will tend to start spinning slowly in a spiral motion around the room, from the floor level upward to the pinnacle of the four gothic arches, which meet into a single point at the summit of the room; and then, your mind will spiral back down, Page 1 of 19 http://www.amatterofmind.us/ PIERRE BEAUDRY’S GALACTIC PARKING LOT by inversion, only to start a similar motion, again, through the experiment of examining in detail each of the three frescos. -

Leonardo Bruni, the Medici, and the Florentine Histories1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace /HRQDUGR%UXQLWKH0HGLFLDQGWKH)ORUHQWLQH+LVWRULHV *DU\,DQ]LWL Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 69, Number 1, January 2008, pp. 1-22 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI3HQQV\OYDQLD3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/jhi.2008.0009 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jhi/summary/v069/69.1ianziti.html Access provided by University of Queensland (30 Oct 2015 04:56 GMT) Leonardo Bruni, the Medici, and the Florentine Histories1 Gary Ianziti Leonardo Bruni’s relationship to the Medici regime raises some intriguing questions. Born in 1370, Bruni was Chancellor of Florence in 1434, when Cosimo de’ Medici and his adherents returned from exile, banished their opponents, and seized control of government.2 Bruni never made known his personal feelings about this sudden regime change. His memoirs and private correspondence are curiously silent on the issue.3 Yet it must have been a painful time for him. Among those banished by the Medici were many of his long-time friends and supporters: men like Palla di Nofri Strozzi, or Rinaldo degli Albizzi. Others, like the prominent humanist and anti-Medicean agita- tor Francesco Filelfo, would soon join the first wave of exiles.4 1 This study was completed in late 2006/early 2007, prior to the appearance of volume three of the Hankins edition and translation of Bruni’s History of the Florentine People (see footnote 19). References to books nine to twelve of the History are consequently based on the Santini edition, cited in footnote 52. -

Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: Rinascita

Niccolo’ Machiavelli (1469‐1527) • Political career (1498‐1512) • Official in Florentine Republic – Diplomat: observes Cesare Borgia – Organizes Florentine militia and military campaign against Pisa – Deposed when Medici return in 1512 – Suspected of treason he is tortured; retired to his estate Major Works: The Prince (1513): advice to Prince, how to obtain and maintain power Discourses on Livy (1517): Admiration of Roman republic and comparisons with his own time – Ability to channel civil strife into effective government – Admiration of religion of the Romans and its political consequences – Criticism of Papacy in Italy – Revisionism of Augustinian Christian paradigm Renaissance Art in Rome Giorgio Vasari: rinascita • Early Renaissance: 1420‐1500c • ‐‐1420: return of papacy (Martin V) to Rome from Avignon • High Renaissance: 1500‐1520/1527 • ‐‐ 1503: Ascension of Julius II as Pope; arrival of Bramante, Raphael and Michelangelo; 1513: Leo X • ‐‐1520: Death of Raphael; 1527 Sack of Rome • Late Renaissance (Mannerism): 1520/27‐1600 • ‐‐1563: Last session of Council of Trent on sacred images Artistic Renaissance in Rome • Patronage of popes and cardinals of humanists and artists from Florence and central/northern Italy • Focus in painting shifts from a theocentric symbolism to a humanistic realism • The recuperation of classical forms (going “ad fontes”) ‐‐Study of classical architecture and statuary; recovery of texts Vitruvius’ De architectura (1414—Poggio Bracciolini) • The application of mathematics to art/architecture and the elaboration of single point perspective –Filippo Brunellschi 1414 (develops rules of mathematical perspective) –L. B. Alberti‐‐ Della pittura (1432); De re aedificatoria (1452) • Changing status of the artist from an artisan (mechanical arts) to intellectual (liberal arts; math and theory); sense of individual genius –Paragon of the arts: painting vs. -

Sight and Touch in the Noli Me Tangere

Chapter 1 Sight and Touch in the Noli me tangere Andrea del Sarto painted his Noli me tangere (Fig. 1) at the age of twenty-four.1 He was young, ambitious, and grappling for the first time with the demands of producing an altarpiece. He had his reputation to consider. He had the spiri- tual function of his picture to think about. And he had his patron’s wishes to address. I begin this chapter by discussing this last category of concern, the complex realities of artistic patronage, as a means of emphasizing the broad- er arguments of my book: the altarpiece commissions that Andrea received were learning opportunities, and his artistic decisions serve as indices of the religious knowledge he acquired in the course of completing his professional endeavors. Throughout this particular endeavor—from his first client consultation to the moment he delivered the Noli me tangere to the Augustinian convent lo- cated just outside the San Gallo gate of Florence—Andrea worked closely with other members of his community. We are able to identify those individuals only in a general sense. Andrea received his commission from the Morelli fam- ily, silk merchants who lived in the Santa Croce quarter of the city and who frequently served in the civic government. They owned the rights to one of the most prestigious chapels in the San Gallo church. It was located close to the chancel, second to the left of the apse.2 This was prime real estate. Renaissance churches were communal structures—always visible, frequently visited. They had a natural hierarchy, dominated by the high altar.