The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Giovanni Della Robbia, 1920. (5) Benedetto and Santi Buglioni, 1921

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 (1) Della Robbias in America, 1912. (2) Luca Della Robbia, 1914. (3) Robbia Heraldry, 1919. (4) Giovanni Della Robbia, 1920. (5) Benedetto and Santi Buglioni, 1921. (6) Andrea Della Robbia and his Atelier, 1922. BY Allan Marquand Chandler R. Post To cite this article: Chandler R. Post (1922) (1) Della Robbias in America, 1912. (2) Luca Della Robbia, 1914. (3) Robbia Heraldry, 1919. (4) Giovanni Della Robbia, 1920. (5) Benedetto and Santi Buglioni, 1921. (6) Andrea Della Robbia and his Atelier, 1922. BY Allan Marquand, The Art Bulletin, 5:2, 41-48, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.1922.11409730 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1922.11409730 Published online: 22 Dec 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Download by: [137.189.171.235] Date: 16 March 2016, At: 07:24 REVIEWS (1) DELLA ROBBIAS IN AMERICA. 1912. (2) LUCA DELLA ROBBIA.1914. (3) ROBBIA HERALDRY, 1919. (4) GIO VANNI DELLA ROBBIA. 1920. (5) BENEDETTO AND SANTI BUGLIONI. 1921. (6) ANDREA DELLA ROBBIA AND HIS ATELIER, 1922. By ALLAN MARQUAND. 4°, ILLUSTRATED. PRINCETON. PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS. One of several reasons for the frequent and justifiable practice of describing our age as Alexandrian is that we have applied ourselves to the business of criticism. The com parison is often made in a somewhat derogatory sense, with the insinuation that critical interests imply lack of creative power and are the concern of less vigorous imaginations. -

Painting in Renaissance Siena

Figure r6 . Vecchietta. The Resurrection. Figure I7. Donatello. The Blood of the Redeemer. Spedale Maestri, Torrita The Frick Collection, New York the Redeemer (fig. I?), in the Spedale Maestri in Torrita, southeast of Siena, was, in fact, the common source for Vecchietta and Francesco di Giorgio. The work is generally dated to the 1430s and has been associated, conjecturally, with Donatello's tabernacle for Saint Peter's in Rome. 16 However, it was first mentioned in the nirieteenth century, when it adorned the fa<;ade of the church of the Madonna della Neve in Torrita, and it is difficult not to believe that the relief was deposited in that provincial outpost of Sienese territory following modifications in the cathedral of Siena in the seventeenth or eighteenth century. A date for the relief in the late I4 5os is not impossible. There is, in any event, a curious similarity between Donatello's inclusion of two youthful angels standing on the edge of the lunette to frame the composition and Vecchietta's introduction of two adoring angels on rocky mounds in his Resurrection. It may be said with little exaggeration that in Siena Donatello provided the seeds and Pius II the eli mate for the dominating style in the last four decades of the century. The altarpieces commissioned for Pienza Cathedral(see fig. IS, I8) are the first to utilize standard, Renaissance frames-obviously in con formity with the wishes of Pius and his Florentine architect-although only two of the "illustrious Si enese artists," 17 Vecchietta and Matteo di Giovanni, succeeded in rising to the occasion, while Sano di Pietro and Giovanni di Paolo attempted, unsuccessfully, to adapt their flat, Gothic figures to an uncon genial format. -

Street Culture Italia

1 Students and Faculty in Pompeii inside cover 2 3 Rome PHOTO // Tanesha Hobson image image 4 5 Venice PHOTO // Marco Sarno CONTENTSPreface 8 Flight Map 12 Art 14 Architecture 32 Religion 50 Culture 68 Program Faculty 86 Tour Guides 88 Itinerary 92 Acknowledgements 94 6 The Fourm, Rome 7 PHOTO // Jessica Demaio The Arts of Italy’s greatest success was in introducing William PREFACE Paterson’s art students to not By Professor Claudia Goldstein only the art and culture of Italy, but to the possibility and joy of international travel. THE ARTS OF ITALY, A TWO WEEK WINTER SESSION COURSE encounters with the towering Palazzo Vecchio and the view — at the top of We then traveled to Rome, the Eternal City, where we immersed WHICH TOOK TWELVE STUDENTS TO SIX CITIES IN ITALY OVER many, many steps — from the medieval church of San Miniato al Monte. ourselves in more than two thousand years of history. We got a fascinating WINTER BREAK 2016-17, WAS CONCEIVED AS AN IDEA — AND TO After we caught our breath, we also caught a beautiful Florentine sunset tour of the Roman Forum from an American architectural historian and SOME EXTENT A PIPE DREAM — ALMOST A DECADE AGO. which illuminated the Cathedral complex, the Palazzo Vecchio, and the architect who has lived in Rome for 25 years, and an expert on Jesuit The dream was to take a group of students on a journey across Italy to show surrounding city and countryside. architecture led us through the Baroque churches of Sant’Ignazio and Il them some of that country’s vast amount of art and architectural history, We spent three beautiful days in Florence — arguably the students’ Gesu’. -

The Della Robbia Frames in the Marche *

ZUZANNA SARNECKA University of Warsaw Institute of Art History ORCID: 0000-0002-7832-4350 Incorruptible Nature: The Della Robbia Frames in the Marche * Keywords: the Marche, Italian Renaissance, Sculpture, Della Robbia, Frames, Terracotta INTRODUCTION In the past the scholarly interest in the Italian Renaissance frames often focused on gilded wooden examples.1 Only more recently the analysis has expanded towards materials such as marble, cartapesta, stucco or glazed terracotta.2 In her recent and extensive monograph on Italian Renaissance frames, Alison Wright has argued that frames embellished and honoured the images they encompassed.3 Due to the markedly non-materialistic perspective, Wright has mentioned the Della Robbia work only in passim.4 Building on Wright’s theoretical framework, the present study discusses the Della Robbia frames in the Marche in terms of the artistic and cul- tural significance of tin-glazed fired clay for the practice of framing Renaissance images. In general, the renewed interest in the Della Robbia works is partially linked to the re-evaluation of terracotta as an independent sculptural medium, with import- ant contributions to the field made by Giancarlo Gentilini.5 Moreover, exhibitions such as La civiltà del cotto in Impruneta, Tuscany in 1980 or Earth and Fire. Italian Terracotta Sculpture from Donatello to Canova at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London in 2002 illustrated the significance of terracotta sculptures in the wider context of the early modern art and culture.6 Importantly for the present study, in 2014 Marchigian authorities and local historians organised an exhibition focused on the artworks of the Della Robbia family surviving in the territory. -

The Early Presence of the Christian Church in Faenza Is Proved by the Participation of Its Bishop Costanzo in the Ro- Man Synod

The early presence of the Christian Church in Faenza is chapel are an example proved by the participation of its bishop Costanzo in the Ro- of the eclectic style of man Synod of AD 313, but the information concerning the the 19th century. The Episcopal Residence and the Cathedral is more obscure. Oc- two paintings on the casional findings convinced the scholars that the sacred place walls, by T. Dal Pozzo, depict scenes of the discovered in a nearby area was the site of the first cathedral. saint’s life. The oldest cathedral on which we have definite information th 4. S. Emiliano was built there during the late 9 century. It was dedicated to 6 7 8 St. Peter Apostle and was located on the podium (a small hill) This Scottish bishop already occupied by a pagan temple. died in Faenza on his way back from Rome 5 9 and has been vener- The idea to rebuild the Cathedral in the same area and, partial- ated here since 1139. ly, on the very foundations of the ancient one, was conceived The saint’s remains by the bishop Federico Manfredi, brother of the princes Car- were placed inside the 4 15 10 lo and Galeotto. Federico saw the new cathedral as the pivot small monument over of Faenza’s urban renovation. The first foundation stone was the altar which is made laid on 26th May 1474 and Federico monitored the works un- of three marble panels: til he fled from Faenza in 1477. His brotherGaleotto took his in the centre is the Vir- place and when the Manfredi family died out, the construc- 3 gin and Child and on the sides the saints Emiliano and Luke, ascribed to the Master of S. -

Resurrecting Della Robbia's Resurrection

Article: Resurrecting della Robbia’s Resurrection: Challenges in the Conservation of a Monumental Renaissance Relief Author(s): Sara Levin, Nick Pedemonti, and Lisa Bruno Source: Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twenty-Four, 2017 Pages: 388–412 Editors: Emily Hamilton and Kari Dodson, with Tony Sigel Program Chair ISSN (print version) 2169-379X ISSN (online version) 2169-1290 © 2019 by American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 727 15th Street NW, Suite 500, Washington, DC 20005 (202) 452-9545 www.culturalheritage.org Objects Specialty Group Postprints is published annually by the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC). It is a conference proceedings volume consisting of papers presented in the OSG sessions at AIC Annual Meetings. Under a licensing agreement, individual authors retain copyright to their work and extend publications rights to the American Institute for Conservation. Unless otherwise noted, images are provided courtesy of the author, who has obtained permission to publish them here. This article is published in the Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twenty-Four, 2017. It has been edited for clarity and content. The article was peer-reviewed by content area specialists and was revised based on this anonymous review. Responsibility for the methods and materials described herein, however, rests solely with the author(s), whose article should not be considered an official statement of the OSG or the AIC. OSG2017-Levin.indd 1 12/4/19 6:45 PM RESURRECTING DELLA ROBBIA’S RESURRECTION: CHALLENGES IN THE CONSERVATION OF A MONUMENTAL RENAISSANCE RELIEF SARA LEVIN, NICK PEDEMONTI, AND LISA BRUNO The Resurrection (ca. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

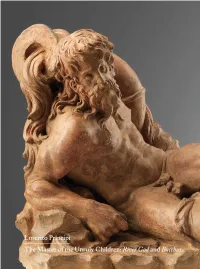

The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus TRINITY

TRINITY FINE ART Lorenzo Principi The Master of the Unruly Children: River God and Bacchus London February 2020 Contents Acknowledgements: Giorgio Bacovich, Monica Bassanello, Jens Burk, Sara Cavatorti, Alessandro Cesati, Antonella Ciacci, 1. Florence 1523 Maichol Clemente, Francesco Colaucci, Lavinia Costanzo , p. 12 Claudia Cremonini, Alan Phipps Darr, Douglas DeFors , 2. Sandro di Lorenzo Luizetta Falyushina, Davide Gambino, Giancarlo Gentilini, and The Master of the Unruly Children Francesca Girelli, Cathryn Goodwin, Simone Guerriero, p. 20 Volker Krahn, Pavla Langer, Guido Linke, Stuart Lochhead, Mauro Magliani, Philippe Malgouyres, 3. Ligefiguren . From the Antique Judith Mann, Peta Motture, Stefano Musso, to the Master of the Unruly Children Omero Nardini, Maureen O’Brien, Chiara Padelletti, p. 41 Barbara Piovan, Cornelia Posch, Davide Ravaioli, 4. “ Bene formato et bene colorito ad imitatione di vero bronzo ”. Betsy J. Rosasco, Valentina Rossi, Oliva Rucellai, The function and the position of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Katharina Siefert, Miriam Sz ó´cs, Ruth Taylor, Nicolas Tini Brunozzi, Alexandra Toscano, Riccardo Todesco, in the history of Italian Renaissance Kleinplastik Zsófia Vargyas, Laëtitia Villaume p. 48 5. The River God and the Bacchus in the history and criticism of 16 th century Italian Renaissance sculpture Catalogue edited by: p. 53 Dimitrios Zikos The Master of the Unruly Children: A list of the statuettes of River God and Bacchus Editorial coordination: p. 68 Ferdinando Corberi The Master of the Unruly Children: A Catalogue raisonné p. 76 Bibliography Carlo Orsi p. 84 THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. 1554) River God terracotta, 26 x 33 x 21 cm PROVENANCE : heirs of the Zalum family, Florence (probably Villa Gamberaia) THE MASTER OF THE UNRULY CHILDREN probably Sandro di Lorenzo di Smeraldo (Florence 1483 – c. -

Summary of the Periodic Report on the State of Conservation, 2006

State of Conservation of World Heritage Properties in Europe SECTION II - Criterion (I). Artistically unique because of its spatial design, the Campo dei Miracoli contains four ITALY absolute architectural masterpieces: the Cathedral, the baptistery, the campanile and the Campo Piazza del Duomo, Pisa Santo. Within these monuments are such world- renowned art treasures as the bronze and mosaic doors of the cathedral, the pulpits in the baptistery Brief description and cathedral, the frescoes of the Campo Santo, Standing in a large green expanse, Piazza del and many others. Duomo houses a group of monuments known the - Criterion (II). The monuments of the Campo del world over. These four masterpieces of medieval Miracoli considerably influenced the development of architecture – the cathedral, the baptistery, the architecture and monumental arts at two different campanile (the 'Leaning Tower') and the cemetery times in history. – had a great influence on monumental art in Italy from the 11th to the 14th century. 1) First, from the 11th century up to 1284, during the epitome of Pisa's prosperity, a new type of church characterized by the refinement of 1. Introduction polychrome architecture and the use of loggias was established. The Pisan style that first appeared with Year(s) of Inscription 1987 the Cathedral can be found elsewhere in Tuscany Agency responsible for site management (notably at Lucques and Pistoia), but also within the Pisan maritime territory, as shown in more humble • Opera Primaziale Pisana form by the "pieve" in Sardegna and Corsica. Piazza Duomo 17 56100 Piza 2) Later, during the 14th century, architecture In Tuscany, Italy Tuscany was dominated by the monumental style E-mail: [email protected] of Giovanni Pisano (who sculpted the pulpit of the Website: www.opapiza.it Cathedral between 1302 and 1311), a new era of pictorial art -the Trecento- was ushered in after the epidemic of the black death (Triumph of Death, a 2. -

New Mexico State Record, 12-20-1918 State Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository New Mexico State Record, 1916-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 12-20-1918 New Mexico State Record, 12-20-1918 State Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_state_record_news Recommended Citation State Publishing Company. "New Mexico State Record, 12-20-1918." (1918). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ nm_state_record_news/128 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico State Record, 1916-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MEW MEXICO STATE 'RECORD SUBSCRIPTION $1.50 SANTA FE, NEW MEXICO, FRIDAY, DECEMBER 20, 1918 NUMBER 223 war, served no military advantage, FLORIDA IS 1STH STATE TO interest of O. H. Ray in the feed to record a single case of the "flu." 1 IIV I 11111 1 OUR IMPORTS NEW MEXICO what?-Glen- and were crimes quite as much as RATIFY DRY AMENDMENT and fuel business, heretofore con Healthy place; hey, rio! frlAft J LAWOillP WILL if they had been committed in times ducted under the firm name of Ful- of peace. The perpetrators should The Florida Legislature in special ler & Ray. The firm will henceforth FROM FAR EAST be apprehended, tried and punish- session has ratified the National Pro- NEWS REVIEW be known as Fuller & Company, and The county school board has de- BE CONSIDERED ed exactly as though no war had hibition Amendment. The score do business at the same old loca- cided to have no Christmas week occurred. -

Sta Te Ne Ws Symphonic Conductor Papers Quote Secret U.S. Prestige

M t //. V TUESDAY, NOVEMBER !, IWO AySlagh Badly Not Preoo Ktui ^turlinfstfr ^oEttittg l|fraU> ' For tin W«Oh Ended ' PeqeoMl e t U / i . ' Oct 29,1986 ^ • : itor.v.M ii/uite Rhnngn Umig k i 'em TWO Women’s Bodetjr C l r ^ of Annual Gi^d Fair GiubHeirsTalk^: t At 13,263 Law tetofhl mOo 40 the Community Baptist Chura Membw Of the Audit will meet -tomorrow at 8 p.m. The FU l day 86-00. Alto Set at St. MaiyV V (M Satelli^^ Ecko Aotdikatfo Hnreoa eC Clhiiglntlea. Reed-Bathn Circle win meeU at Manchester--—4 hf VUlage Charm . y . the home of Mrs. L T . w o o l , jitofliaito’ ! » ' wUI be ipon- dell, ISO Oak Bt,.and the WlUlng The annual fair of St. Mary’s I.TIie aatellltb Echo wlU be dls- FbesM m 2-tltf ^ rr*\ Ort BomU Episcopal OuUd' win take place eussed' tiy KeEineth' Sklimer of the Ones Circle will iheet at the home MANCHESTER, CONN., WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 2, 1M6 (CMssHted no Face 82) PRICE riVECKNTK m S toJB P.m. toi the of Mrs: Jtoes Bldef,_ 85 Wads on Thursday, Nov. 10, at 2 p.m. SduUiam New Engtend Telephone: VOL. LXXli; NO. 28 " (TWENTT-FOUIt PAGES—TWO SECTIONS—PLUS TABLOID) lihgilttMl b in e ( Methodist worth 8 t ' .. in.the hall of the old pfYblb house. B. P. Itury Is «en- Cheese will be aokfhesn* the.pn-, Oo. at a meeting of the 60-60 club •faf'dntnnan. an— Eva Holmea M Church St, trance by Mrs. -

Catalogue Entry

CALLISTO FINE ARTS 17 Georgian House 10 Bury Street London SW1Y 6AA +44 (0)207 8397037 [email protected] www.callistoart.com Jacopo della Quercia (Quercegrossa, c.1372 – Siena, 1438) Warrior Saint c.1426-1430 Marble 53x23x14 cm Bibliography: Casciaro, Raffaele, “Celsis Florentia nota tropheis”, in Raffaele Casciaro e Paola Di Girolami, a cura di, Jacopo della Quercia ospite a Ripatransone, Tracce di scultura toscana tra Emilia e Marche. Ripatransone, Firenze, 2008, pp. 21-39 Custoza, Gian Camillo, con prefazione di Giancarlo Gentilini, “Jacopo della Quercia. San Paolo”, Venezia, 2011 Gentilini, Giancarlo, introduzione di, David Lucidi, con la collaborazione di, “Scultura italiana del Rinascimento”, Firenze, 2013, pp. 13-15 CALLISTO FINE ARTS 17 Georgian House 10 Bury Street London SW1Y 6AA +44 (0)207 8397037 [email protected] www.callistoart.com Gentilini, Giancarlo, scheda, in Massimo Pulini, a cura di, “Lo Studiolo di Baratti”, Cesena, 2010, cat. 1, pp. 30-33 Ortenzi, Francesco, in “Lo Studiolo di Baratti”, catalogo della mostra (Cesena 2010), a cura di M. Pulini, Cesena 2010, pp. 30-33 n. 1; Ortenzi, Francesco, scheda, in Raffaele Casciaro e Paola Di Girolami, a cura di, “Jacopo Della Quercia ospite a Ripatransone. Tracce di scultura toscana tra Emilia e Marche”. Ripatransone, Firenze, 2008, cat. 5, pp. 64-68 Exhibitions: “Scultura italiana del Rinascimento”, a cura di Giancarlo Gentilini e David Lucidi, Firenze, The Westin Excelsior, 5-9 ottobre 2013 “Lo Studiolo di Baratti”, a cura di Massimo Pulini, Cesena, Galleria Comunale d’Arte, 6 febbraio – 11 aprile 2010 “Jacopo della Quercia ospite a Ripatransone. Tracce di scultura toscana tra Emilia e Marche”, a cura di Raffaele Casciaro e Paola Di Girolami, Ripatransone, Chiesa di Sant’Agostino, 28 giugno – 14 settembre 2008 This marvellous work has been attributed to Jacopo della Quercia by Francesco Ortenzi in 2008 and by Giancarlo Gentilini in 2011.