Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of Object: Apollo and Daphne Location: Rome, Italy Holding

Name of Object: Apollo and Daphne Location: Rome, Latium, Italy Holding Museum: Borghese Gallery Date of Object: 1622–1625 Artist(s) / Craftsperson(s): Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598, Naples-1680, Rome) Museum Inventory Number: CV Material(s) / Technique(s): Marble Dimensions: h: 243 cm Provenance: Borghese Collection Type of object: Sculpture Description: This sculpture is considered one of the masterpieces in the history of art. Bernini began sculpting it in 1622 after he finished The Rape of Proserpina. He stopped working on it from 1623 to 1624 to sculpt David, before completing it in 1625. With notable technical accuracy, the natural agility of this work shows the astonishing moment when the nymph turns into a laurel tree. The artist uses his exceptional technical skill to turn the marble into roots, leaves and windswept hair. Psychological research, combined with typically Baroque expressiveness, renders the emotion of Daphnes terror, caught by the god in her desperate journey, still ignorant of her ongoing transformation. Apollo, thinking he has achieved his objective, is caught in the moment he becomes aware of the metamorphosis, before he is able to react, watching astonished as his victim turns into a laurel tree. For Apollos head, Bernini looked to Apollo Belvedere, which was in the Vatican at the time. The base includes two scrolls, the first containing the lines of the distich by Maffeo Barberini, a friend of Cardinal Scipione Borghese and future Pope Urban VIII. It explores the theme of vanitas in beauty and pleasure, rendered as a Christian moralisation of a profane theme. The second scroll was added in the mid-1700s. -

Vittorio Sgarbi Racconta Parma E I Suoi Artisti

66 IL UOCO DELLA ELLEZZA 67 MARZO MARZO 2020 F B 2020 VITTORIO SGARBI RACCONTA PARMA E I SUOI ARTISTI È ENORME L’EREDITÀ LASCIATA DA CORREGGIO E PARMIGIANINO, I DUE GENI DEL RINASCIMENTO CUI È DEDICATA LA MOSTRA MULTIMEDIALE “L’ALCHIMIA DELLA GRAZIA” a cura di Patrizia Maglioni a Parma che si svela “l‘alchimia della grazia”. Se la grazia avesse un nome, sarebbe quello di Correggio, o quello del Parmigianino. I due grandi artisti parmigiani sono i protagonisti della mostra multimediale ospitata dal 20 marzo al 13 dicembre 2020 nella prestigiosa sede delle ÈScuderie della Pilotta, primo grande evento di Parma Capitale della Cultura 2020. Tra le tante iniziative, IL FUOCO DELLA BELLEZZA DELLA FUOCO IL Correggio, Camera della Badessa E PARMIGIANINO CORREGGIO vi sarà anche quella che farà tornare a nuova vita i Chiostri del Correggio, un THE LEGACY LEFT BY CORREGGIO AND PARMIGIANINO, THE TWO 68 progetto di rigenerazione urbana che interessa in particolare l’ex convento GENIUSES OF RENAISSANCE TO WHOM THE MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION 69 benedettino di San Paolo, dove si trova la celebre Camera della Badessa affrescata “THE ALCHEMY OF GRACE” IS DEDICATED, IS ENORMOUS dal Correggio nel 1518-19. In questo prezioso bene storico monumentale si pensa MARZO MARZO 2020 anche di inserire un museo nazionale innovativo di enogastronomia. 2020 PARMA AND ITS ARTISTS is the poet of harmony, Correggio is and the Lamentation over the Dead “Correggio è autore di opere meravigliose che hanno evocato It is in Parma that “the alchemy of the painter of harmony. He is a point Christ, works of great appeal and letteratura: Stendhal, Mengs, la Madonna della Scodella, la grace” is revealed. -

Architectural Perspectives in the Cathedral of Palermo: Image-Based Modeling for Cultural Heritage Understanding and Enhancement

Inzerillo, L. and Santagati, C. (2015).Xjenza Online, 3:69{75. Xjenza Online - Journal of The Malta Chamber of Scientists www.xjenza.org DOI: 10.7423/XJENZA.2015.1.10 Research Article Architectural Perspectives in the Cathedral of Palermo: Image-Based Modeling for Cultural Heritage Understanding and Enhancement L. Inzerillo1;3, C. Santagati2;3 1University of Palermo, Department of Architecture, viale delle Scienze, Edificio 8, 90128, Palermo 2University of Catania, Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture, viale Andrea Doria n. 6, 95125, Catania 3Euro Mediterranean Institute of Science and Technology (IEMEST), Via Emerico Amari, 123 - 90139 Palermo Abstract. Palermo offers a repertoire of both artistic matic space is transformed into an aberrated pyramidal and architectural solid perspective of great beauty and prism where narratives are represented, subjects charac- in large quantity. This paper addresses the problem of terizing the context (D'Alessandro, Inzerillo & Pizzurro, the 3D survey of these works and their related study 1983; D'Alessandro & Pizzurro, 1989; Inzerillo, 2004, through the use of image-based modelling (IBM) tech- 2012). niques. We propose, as case studies, the use of IBM techniques inside the Cathedral of Palermo. Indeed, the church houses a huge and rich sculptural repertoire, dat- ing back to 16th century, which constitutes a valid field of IBM techniques application. The aim of this study is to demonstrate the effective- ness and potentiality of these techniques for geometric analysis of sculptured works. Indeed, usually the survey of these artworks is very difficult due the geometric com- plexity, typical of sculptured elements. In this study, we analysed cylindrical and planar geometries as well as carrying out an application of perspective return. -

Gian Cristoforo Romano in Rome: with Some Thoughts on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of Julius II

Gian Cristoforo Romano in Rome: With some thoughts on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of Julius II Sally Hickson University of Guelph En 1505, Michel-Ange est appelé à Rome pour travailler sur le tombeau monumental du pape Jules II. Six mois plus tard, alors que Michel-Ange se trouvait à Carrare, le sculpteur et antiquaire Gian Cristoforo Romano était également appelé à Rome par Jules II. En juin 1506, un agent de la cour de Mantoue rapportait que les « premiers sculpteurs de Rome », Michel-Ange et Gian Cristoforo Romano, avaient été appelés ensemble à Rome afin d’inspecter et d’authentifier le Laocoön, récemment découvert. Que faisait Gian Cristoforo à Rome, et que faisait-il avec Michel-Ange? Pourquoi a-t-il été appelé spécifi- quement pour authentifier une statue de Rhodes. Cet essai propose l’hypothèse que Gian Cristoforo a été appelé à Rome par le pape probablement pour contribuer aux plans de son tombeau, étant donné qu’il avait travaillé sur des tombeaux monumentaux à Pavie et Crémone, avait voyagé dans le Levant et vu les ruines du Mausolée d’Halicarnasse, et qu’il était un sculpteur et un expert en antiquités reconnu. De plus, cette hypothèse renforce l’appartenance du développement du tombeau de Jules II dans le contexte anti- quaire de la Rome papale de ce temps, et montre, comme Cammy Brothers l’a avancé dans son étude des dessins architecturaux de Michel-Ange (2008), que les idées de ce dernier étaient influencées par la tradition et par ses contacts avec ses collègues artistes. -

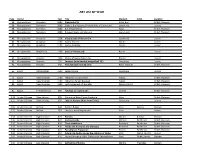

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

California State University, Northridge

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Palazzo del Te: Art, Power, and Giulio Romano’s Gigantic, yet Subtle, Game in the Age of Charles V and Federico Gonzaga A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies with emphases in Art History and Political Science By Diana L. Michiulis December 2016 The thesis of Diana L. Michiulis is approved: ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. Jean-Luc Bordeaux Date ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. David Leitch Date ___________________________________ _____________________ Dr. Margaret Shiffrar, Chair Date California State University, Northridge ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to convey my deepest, sincere gratitude to my Thesis Committee Chair, Dr. Margaret Shiffrar, for all of her guidance, insights, patience, and encourage- ments. A massive "merci beaucoup" to Dr. Jean-Luc Bordeaux, without whom completion of my Master’s degree thesis would never have been fulfilled. It was through Dr. Bordeaux’s leadership, patience, as well as his tremendous knowledge of Renaissance art, Mannerist art, and museum art collections that I was able to achieve this ultimate goal in spite of numerous obstacles. My most heart-felt, gigantic appreciation to Dr. David Leitch, for his leadership, patience, innovative ideas, vast knowledge of political-theory, as well as political science at the intersection of aesthetic theory. Thank you also to Dr. Owen Doonan, for his amazing assistance with aesthetic theory and classical mythology. I am very grateful as well to Dr. Mario Ontiveros, for his advice, passion, and incredible knowledge of political art and art theory. And many thanks to Dr. Peri Klemm, for her counsel and spectacular help with the role of "spectacle" in art history. -

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New York | November 17, 2020 Impressionist & Modern Art New York | Tuesday November 17, 2020 at 5pm EST BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS COVID-19 SAFETY STANDARDS 580 Madison Avenue New York Register to bid online by visiting Bonhams’ galleries are currently New York, New York 10022 Molly Ott Ambler www.bonhams.com/26154 subject to government restrictions bonhams.com +1 (917) 206 1636 and arrangements may be subject Bonded pursuant to California [email protected] Alternatively, contact our Client to change. Civil Code Sec. 1812.600; Services department at: Bond No. 57BSBGL0808 Preeya Franklin [email protected] Preview: Lots will be made +1 (917) 206 1617 +1 (212) 644 9001 available for in-person viewing by appointment only. Please [email protected] SALE NUMBER: contact the specialist department IMPORTANT NOTICES 26154 Emily Wilson on impressionist.us@bonhams. Please note that all customers, Lots 1 - 48 +1 (917) 683 9699 com +1 917-206-1696 to arrange irrespective of any previous activity an appointment before visiting [email protected] with Bonhams, are required to have AUCTIONEER our galleries. proof of identity when submitting Ralph Taylor - 2063659-DCA Olivia Grabowsky In accordance with Covid-19 bids. Failure to do this may result in +1 (917) 717 2752 guidelines, it is mandatory that Bonhams & Butterfields your bid not being processed. you wear a face mask and Auctioneers Corp. [email protected] For absentee and telephone bids observe social distancing at all 2077070-DCA times. Additional lot information Los Angeles we require a completed Bidder Registration Form in advance of the and photographs are available Kathy Wong CATALOG: $35 sale. -

'Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain' Review: A

ART REVIEW ‘Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain’ Review: A Taste of Spain Embodying the ideas that flourished in Renaissance Italy, Alonso Berruguete became a sort of Iberian Michelangelo. Alonso Berruguete’s ‘Calvary Group: Crucified Christ Flanked by the Virgin Mary and St. John the retablo mayor of San Benito el Real, top PHOTO: MUSEO NACIONAL DE ESCULTURA, VALLADOLID, SPAIN the Evangelist’ (1526/33) from the retablo mayor of San Benito el Real, Eric Gibson 14 de enero de 2020 Washington We generally associate the word “Renaissance” with art produced in Italy from roughly the 15th through 16th centuries. But the ideas that flowered there spread far and wide —including to Spain, where their greatest exponent was Alonso Berruguete, an electrifying sculptor now the subject of a small show at the National Gallery of Art. Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain National Gallery of Art Through Feb. 17 Organized by C.D. Dickerson III of the National Gallery, Mark McDonald of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Wendy Sepponen of the Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University, where it travels after closing in Washington, “Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain” brings together about three dozen works in all media, along with about a dozen more works by other artists for context, including his painter father, Pedro. This is the first National Gallery show exclusively devoted to so-called Golden Age Spanish sculpture, and one’s reaction after taking in its rich polychromy, emotional intensity and ability to engage with the viewer in a way that makes all other European sculpture of the period seem diffident or aloof is to say: More, please. -

Angelo Caroselli (Roma, 1585 – 1652) the Penitent Magdalene Oil on Canvas Ca

Angelo Caroselli (Roma, 1585 – 1652) The penitent Magdalene Oil on canvas Ca. 1610-15 59 x 75 cm. Angelo Caroselli was born in Rome, the son of Achilles, a dealer in second-hand goods who bought broken silver and gold objects and was a minor but dedicated collector of paintings by renowned painters of the past1. Caroselli was a self-taught, experimental and intellectually curious painter. By 1604 he appears as one of the artists registered at the Accademia di San Luca in Rome, an institution with which he maintained some relationship, at least in the years 1608 and 1636. Caroselli broadened his knowledge of art outside the frontiers of his native region with early trips to Florence in 1605 and Naples in 1613. He was primarily based in Rome from approximately 1615, the year of his first marriage to Maria Zurca from Sicily, and it was there that he must have had a large studio although little is known on this subject. Passeri states that among the regulars in the “bottega” were the Tuscan Pietro Paolini and the painters Francesco Lauri and possibly Tommaso Donnini. Caroselli always kept abreast of the latest developments in art, particularly since Paolini, who arrived in his studio around 1619, initiated him into the first phase of Caravaggesque naturalism. Caroselli’s use of this language essentially relates to form and composition rather than representing a profound adherence to the new pictorial philosophy. Nonetheless, around 1630 it is difficult to distinguish between his works and those of his follower Paolini, given that both artists were fully engaged in the new artistic trend. -

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus

Core Knowledge Art History Syllabus This syllabus runs 13 weeks, with 2 sessions per week. The midterm is scheduled for the end of the seventh week. The final exam is slated for last class meeting but might be shifted to an exam period to give the instructor one more class period. Goals: • understanding of the basic terms, facts, and concepts in art history • comprehension of the progress of art as fluid development of a series of styles and trends that overlap and react to each other as well as to historical events • recognition of the basic concepts inherent in each style, and the outstanding exemplars of each Lecture Notes: For each lecture a number of exemplary works of art are listed. In some cases instructors may wish to discuss all of these works; in other cases they may wish to focus on only some of them. Textbooks: It should be possible to teach this course using any one of the five texts listed below as a primary textbook. Cole et al., Art of the Western World Gardner, Art Through the Ages Janson, History of Art, 2 vols. Schneider Adams, Laurie, A History of Western Art Stokstad, Art History, 2 vols. Writing Assignments: A short, descriptive paper on a single work of art or topic would be in order. Syllabus created by the Core Knowledge Foundation 1 https://www.coreknowledge.org/ Use of this Syllabus: This syllabus was created by Bruce Cole, Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts, Indiana University, as part of What Elementary Teachers Need to Know, a teacher education initiative developed by the Core Knowledge Foundation. -

Illustrations Ij

Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiii Illustrations ij Fig. 1. Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1015, Doors of St. Michael’s, Hildesheim, Germany. Fig. 2. Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1425, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Flo- rence. Fig. 3. Bernardo Rossellino, Facade of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 4. Bernardo Rossellino, Interior of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 5. Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495–98, Refectory of the Monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Fig. 6. Anonymous Pisan artist, Pisa Cross #15, late twelfth century, Museo Civico, Pisa. Fig. 7. Anonymous artist, Cross of San Damiano, late twelfth century, Basilica of Santa Chiara, Assisi. Fig. 8. Giotto di Bondone, Cruci‹xion, ca. 1305, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua. Fig. 9. Masaccio, Trinity Fresco, ca. 1427, Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Fig. 10. Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Altarpiece of St. Francis, 1235, Church of San Francesco, Pescia. Fig. 11. St. Francis Master, St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, early four- teenth century, Upper Church of San Francesco, Assisi. Fig. 12. Anonymous Florentine artist, Detail of the Misericordia Fresco from the Loggia del Bigallo, 1352, Council Chamber, Misericor- dia Palace, Florence. Fig. 13. Florentine artist (Francesco Rosselli?), “Della Catena” View of Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiv ILLUSTRATIONS Florence, 1470s, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Fig. 14. Present-day view of Florence from the Costa San Giorgio. Fig. 15. Nicola Pisano, Nativity Panel, 1260, Baptistery Pulpit, Baptis- tery, Pisa. Fig.