Making and Unmaking Sculpture in Fifteenth- Century Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paintings and Sculpture Given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr

e. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE COLLECTIONS OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART \YASHINGTON The National Gallery will open to the public on March 18, 1941. For the first time, the Mellon Collection, deeded to the Nation in 1937, and the Kress Collection, given in 1939, will be shown. Both collections are devoted exclusively to painting and sculpture. The Mellon Collection covers the principal European schools from about the year 1200 to the early XIX Century, and includes also a number of early American portraits. The Kress Collection exhibits only Italian painting and sculpture and illustrates the complete development of the Italian schools from the early XIII Century in Florence, Siena, and Rome to the last creative moment in Venice at the end of the XVIII Century. V.'hile these two great collections will occupy a large number of galleries, ample space has been left for future development. Mr. Joseph E. Videner has recently announced that the Videner Collection is destined for the National Gallery and it is expected that other gifts will soon be added to the National Collection. Even at the present time, the collections in scope and quality will make the National Gallery one of the richest treasure houses of art in the wor 1 d. The paintings and sculpture given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr. Mellon have been acquired from some of -2- the most famous private collections abroad; the Dreyfus Collection in Paris, the Barberini Collection in Rome, the Benson Collection in London, the Giovanelli Collection in Venice, to mention only a few. -

The Master of the Unruly Children and His Artistic and Creative Identities

The Master of the Unruly Children and his Artistic and Creative Identities Hannah R. Higham A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham For The Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Art History, Film and Visual Studies School of Languages, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines a group of terracotta sculptures attributed to an artist known as the Master of the Unruly Children. The name of this artist was coined by Wilhelm von Bode, on the occasion of his first grouping seven works featuring animated infants in Berlin and London in 1890. Due to the distinctive characteristics of his work, this personality has become a mainstay of scholarship in Renaissance sculpture which has focused on identifying the anonymous artist, despite the physical evidence which suggests the involvement of several hands. Chapter One will examine the historiography in connoisseurship from the late nineteenth century to the present and will explore the idea of the scholarly “construction” of artistic identity and issues of value and innovation that are bound up with the attribution of these works. -

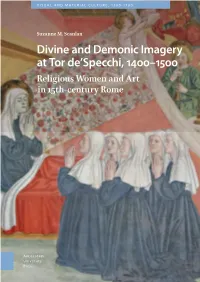

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Gian Cristoforo Romano in Rome: with Some Thoughts on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of Julius II

Gian Cristoforo Romano in Rome: With some thoughts on the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus and the Tomb of Julius II Sally Hickson University of Guelph En 1505, Michel-Ange est appelé à Rome pour travailler sur le tombeau monumental du pape Jules II. Six mois plus tard, alors que Michel-Ange se trouvait à Carrare, le sculpteur et antiquaire Gian Cristoforo Romano était également appelé à Rome par Jules II. En juin 1506, un agent de la cour de Mantoue rapportait que les « premiers sculpteurs de Rome », Michel-Ange et Gian Cristoforo Romano, avaient été appelés ensemble à Rome afin d’inspecter et d’authentifier le Laocoön, récemment découvert. Que faisait Gian Cristoforo à Rome, et que faisait-il avec Michel-Ange? Pourquoi a-t-il été appelé spécifi- quement pour authentifier une statue de Rhodes. Cet essai propose l’hypothèse que Gian Cristoforo a été appelé à Rome par le pape probablement pour contribuer aux plans de son tombeau, étant donné qu’il avait travaillé sur des tombeaux monumentaux à Pavie et Crémone, avait voyagé dans le Levant et vu les ruines du Mausolée d’Halicarnasse, et qu’il était un sculpteur et un expert en antiquités reconnu. De plus, cette hypothèse renforce l’appartenance du développement du tombeau de Jules II dans le contexte anti- quaire de la Rome papale de ce temps, et montre, comme Cammy Brothers l’a avancé dans son étude des dessins architecturaux de Michel-Ange (2008), que les idées de ce dernier étaient influencées par la tradition et par ses contacts avec ses collègues artistes. -

The Della Robbia Frames in the Marche *

ZUZANNA SARNECKA University of Warsaw Institute of Art History ORCID: 0000-0002-7832-4350 Incorruptible Nature: The Della Robbia Frames in the Marche * Keywords: the Marche, Italian Renaissance, Sculpture, Della Robbia, Frames, Terracotta INTRODUCTION In the past the scholarly interest in the Italian Renaissance frames often focused on gilded wooden examples.1 Only more recently the analysis has expanded towards materials such as marble, cartapesta, stucco or glazed terracotta.2 In her recent and extensive monograph on Italian Renaissance frames, Alison Wright has argued that frames embellished and honoured the images they encompassed.3 Due to the markedly non-materialistic perspective, Wright has mentioned the Della Robbia work only in passim.4 Building on Wright’s theoretical framework, the present study discusses the Della Robbia frames in the Marche in terms of the artistic and cul- tural significance of tin-glazed fired clay for the practice of framing Renaissance images. In general, the renewed interest in the Della Robbia works is partially linked to the re-evaluation of terracotta as an independent sculptural medium, with import- ant contributions to the field made by Giancarlo Gentilini.5 Moreover, exhibitions such as La civiltà del cotto in Impruneta, Tuscany in 1980 or Earth and Fire. Italian Terracotta Sculpture from Donatello to Canova at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London in 2002 illustrated the significance of terracotta sculptures in the wider context of the early modern art and culture.6 Importantly for the present study, in 2014 Marchigian authorities and local historians organised an exhibition focused on the artworks of the Della Robbia family surviving in the territory. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

Nevola Siena Companion Volume Essay 201216

Pre-print text, not for circulation. Fabrizio Nevola (University of Exeter) ‘“per queste cose ognuno sta in santa pace et in concordia”: Understanding urban space in Renaissance Siena’, in Santa Casciani ed., A Companion to Late Medieval and Early Modern Siena (Leiden and Boston: Brill 2018). Abstract: This chapter offers a longue durée history of Siena’s urban development from the fourteenth century through to the early years of Medici domination (c. 1300-1600). As is well known, Siena offers a precocious example of urban design legislation around the piazza del Campo, which included paving, zoning rules, and rulings on the aesthetics of buildings facing onto the piazza. Such planning rules spread to encompass much of the city fabric through the fifteenth century, so that when the Medici took over the city, there is evidence of their surprise at the way urban improvement was enshrined as a core civic duty. While a focus of the chapter will look at urban planning legislation and its effects on the evolving built fabric over nearly three centuries, it will also consider how public urban space was used. Here too, there are continuities in the ritual practices that activated and inscribed meaning on the squares and streets as well as religious and secular buildings and monuments. It will be shown then that, as Bernardino da Siena’s commentary on Lorenzetti’s famous frescoes show, the built city is integral to the social interactions of its citizens. Illustrations: 1. Ambrogio Lorenzetti (1338-40), Sala della Pace, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena 2. Piazza del Campo with Palazzo Sansedoni and Fonte Gaia, showing market stalls in place in a photo by Paolo Lombardi, c. -

Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci: Beauty. Politics, Literature and Art in Early Renaissance Florence

! ! ! ! ! ! ! SIMONETTA CATTANEO VESPUCCI: BEAUTY, POLITICS, LITERATURE AND ART IN EARLY RENAISSANCE FLORENCE ! by ! JUDITH RACHEL ALLAN ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT ! My thesis offers the first full exploration of the literature and art associated with the Genoese noblewoman Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci (1453-1476). Simonetta has gone down in legend as a model of Sandro Botticelli, and most scholarly discussions of her significance are principally concerned with either proving or disproving this theory. My point of departure, rather, is the series of vernacular poems that were written about Simonetta just before and shortly after her early death. I use them to tell a new story, that of the transformation of the historical monna Simonetta into a cultural icon, a literary and visual construct who served the political, aesthetic and pecuniary agendas of her poets and artists. -

Leonardo Da Vinci Tour

In the footsteps of Leonardo Departure: 04 May 2019 Leonardo Tour Florence Venice Milan Italy Italy Italy 3 3 3 5 7 DESTINATIONS HOTELS TICKETS TRANSFERS NIGHTS Florence From day 1 to day 4 (04/May/2019 > 07/May/2019) Italy About the city Florence is as vital and beautiful today as when its wool and silk merchants and bankers revolutionized the 3 economy of 13th century Tuscany, and the art of Dante and Michelangelo stunned the world. Florence was the centre of the Italian Renaissance. The fruits of the city’s rebirth are still evident in its seemingly endless array of museums, churches and palazzi. With its historic centre classified as a UNESCO World Heritage site, the Duomo, the elegant and beautiful cathedral, dominates the city and is an unmistakable reference point in your wanderings. The River Arno, which cuts through the oldest part of the city, is crowned with the Ponte Vecchio bridge lined with shops and held up by stilts. Dating back to the 14th century, it is the only bridge that survived attacks during WWII. Standing by the river at night, when the city is illuminated with a myriad twinkling lights, is unforgettable. But more remains of Florence’s incomparable heritage than stones and paint, the city’s indomitable spirit has also survived the centuries, ensuring Florentine life today its liveliness and sophistication. Points of interest Boboli Gardens,Florence Cathedral,Fountain of Neptune,Cathedral of Santa María de la Flor,Florence City Center,Piazza della Signoria,Hippodrome of the Visarno,Basilica of Santa Maria Novella,Meyer -

The Choir Books of Santa Maria in Aracoeli and Patronage Strategies of Pope Alexander VI

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School January 2013 The hoirC Books of Santa Maria in Aracoeli and Patronage Strategies of Pope Alexander VI Maureen Elizabeth Cox University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Scholar Commons Citation Cox, Maureen Elizabeth, "The hoC ir Books of Santa Maria in Aracoeli and Patronage Strategies of Pope Alexander VI" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/4657 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Choir Books of Santa Maria in Aracoeli and Patronage Strategies of Pope Alexander VI by Maureen Cox-Brown A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts School of Art and Art History College of The Arts University of South Florida Major Professor: Helena K. Szépe Ph.D. Elisabeth Fraser Ph.D. Mary Fournier Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 28, 2013 Keywords: Humanism, Antonio da Monza, illuminated manuscripts, numismatics, Aesculapius, Pinturicchio, Borgia Copyright © 2013, Maureen Cox-Brown DEDICATION This is lovingly dedicated to the memory of my mother and her parents. Et benedictio Dei omnipotentis, Patris et Filii et Spiritus Sancti descendat super vos et maneat semper ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. -

Measuring and Making the World: Self-Promotion, Cosmology and Elite Appeal in Filarete's Libro Architettonico

MEASURING AND MAKING THE WORLD: SELF-PROMOTION, COSMOLOGY AND ELITE APPEAL IN FILARETE’S LIBRO ARCHITETTONICO HELENA GUZIK UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD UNITED KINGDOM Date of receipt: 21st of February, 2020 Date of acceptance: 23rd of July, 2020 ABSTRACT Antonio Averlino (Filarete) (c. 1400-c. 1469) is best remembered for his architectural treatise, the Libro architettonico. Despite a longstanding tradition, beginning with Vasari, of dismissing Filarete as a mediocre artist with ridiculous ideas, his treatise ended up in some of the most prestigious courts within and beyond Italy. This article, in a corrective to that narrative, argues that Filarete was an incredibly ambitious artist and that the Libro was his attempt to channel intellectual trends of interest to the fifteenth-century ruling elite whose patronage he courted. It begins by situating the Libro within the broader context of Filarete’s consistent self-promotion and shrewd networking throughout his career. It then examines, through analysis of the text and illustrations, how the Libro was designed both to promote Filarete to his patrons and appeal to contemporary patronage tastes through its use of specific themes: ideal urban design, cosmology, and universal sovereignty. KEYWORDS Architectural Treatise, Cosmology, Intellectual Networks, Italian Court Culture, Fifteenth-century Art. CAPITALIA VERBA Tractatus architecturae, Cosmologia, Reta sapientium, Cultura iudiciaria Italica, Ars saeculi quindecimi. IMAGO TEMPORIS. MEDIUM AEVUM, XV (2021): 387-412 / ISSN 1888-3931 / DOI 10.21001/itma.2021.15.13 387 388 HELENA GUZIK Like many of his humanist contemporaries, Antonio Averlino (c. 1400-c. 1469) had a predilection for wordplay. Adopting the nickname “Filarete” later in life, he 2 cultivated his identity as a “lover of virtue”, the name’s Greek1 meaning.