Long-Term Professional Bonds in Quattrocento Florence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: a Historiographical Survey

chapter 11 The Medici Palace, Cosimo the Elder, and Michelozzo: A Historiographical Survey Emanuela Ferretti* The Medici Palace has long been recognized as an architectural icon of the Florentine Quattrocento. This imposing building, commissioned by Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici (1389–1464), is a palimpsest that reveals complex layers rooted in the city’s architectural, urban, economic, and social history. A symbol – just like its patron – of a formidable era of Italian art, the palace on the Via Larga represents a key moment in the development of the palace type and and influenced every other Italian centre. Indeed, it is this building that scholars have identified as the prototype for the urban residence of the nobility.1 The aim of this chapter, based on a great wealth of secondary literature, including articles, essays, and monographs, is to touch upon several themes and problems of relevance to the Medici Palace, some of which remain unresolved or are still debated in the current scholarship. After delineating the basic construction chronology, this chapter will turn to questions such as the patron’s role in the building of his family palace, the architecture itself with regards to its spatial, morphological, and linguistic characteristics, and finally the issue of author- ship. We can try to draw the state of the literature: this preliminary historio- graphical survey comes more than twenty years after the monograph edited by Cherubini and Fanelli (1990)2 and follows an extensive period of innovative study of the Florentine early Quattrocento,3 as well as the fundamental works * I would like to thank Nadja Naksamija who checked the English translation, showing many kindnesses. -

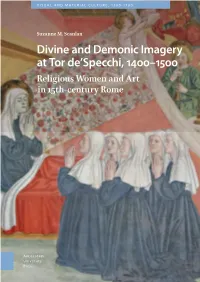

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

The Importance of Cosimo De Medici in Library History

THE IMPORTANCE OF COSIMO DE MEDICI IN LIBRARY HISTORY by William F Meehan III osimo de Medici, the aristocratic banker in Gern1any are 'epoch-making" (Holmes, 1969 p. and statesman who enlivened philan 119). thropy in Renaissance Florence might When it came to his personal book collection, have made his greatest contribution to [Q Cosin10 preferred quality over quantity, and he added the arts through his patronage of human to his library wisely. After growing up in a home with ist libraries. Cosima hin1self accumulated a superb only three books, Cosima by the age of 30 had as personal collection, but his three major library initia sembled a library of about 70 exquisite volumes. The tives were charitable activities and included Italy's first collection reflected his literary taste and consisted of public library, which made its way to the magnificent classical texts as well as a mix of secular and sacred library founded generations later by one of his descen works typical of collections at the time. Sening his dants. library, as well as other Florentine humanist libraries, Cosima's patronage of libraries flourished when a apart from others in Italy in the first half of the four small group of Florentine intellectuals leading a revival teenth century was the accession of Greek texts, which of the classical world and litterae humaniores sought were exceedingly scarce at th time but central to the his support. They fostered a milieu that engendered an unifying theme of Cosima's excell nt collection as well appreciation for books and learning in the benefactor as a principal scholarly interest of the humanists. -

Donatello's Terracotta Louvre Madonna

Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sandra E. Russell May 2015 © 2015 Sandra E. Russell. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning by SANDRA E. RUSSELL has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Professor of Art History Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract RUSSELL, SANDRA E., M.A., May 2015, Art History Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw A large relief at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (R.F. 353), is one of several examples of the Madonna and Child in terracotta now widely accepted as by Donatello (c. 1386-1466). A medium commonly used in antiquity, terracotta fell out of favor until the Quattrocento, when central Italian artists became reacquainted with it. Terracotta was cheap and versatile, and sculptors discovered that it was useful for a range of purposes, including modeling larger works, making life casts, and molding. Reliefs of the half- length image of the Madonna and Child became a particularly popular theme in terracotta, suitable for domestic use or installation in small chapels. Donatello’s Louvre Madonna presents this theme in a variation unusual in both its form and its approach. In order to better understand the structure and the meaning of this work, I undertook to make some clay works similar to or suggestive of it. -

The Magic of Donatello Andrew Butterfield

The Magic of Donatello Andrew Butterfield Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: smith Lorenzo Ghiberti, and another Renaissance Masterpieces from young Florentine goldsmith, Filippo Florence Cathedral Brunelleschi—the future architect— an exhibition at the Museum of came in second. A new era in the his- Biblical Art, New York City, tory of art had begun. February 20–June 14, 2015. Like all revolutions, the transfor- Catalog of the exhibition edited by mation of the arts in early-fifteenth- Timothy Verdon and Daniel M. Zolli. century Florence can never be fully Museum of Biblical Art/Giles, explained; at best we can only identify 200 pp., $49.95 some contributing causes. Stimulated in part by the city’s soaring prosperity The Museum of Biblical Art, lodged and growing hegemony, around 1400 in a relatively small space on Broad- the wealthy merchants who ran Flor- way near Lincoln Center, is now show- ence began to pour unprecedented ing nine sculptures by Donatello, one amounts of cash into new buildings, of the greatest of all Renaissance art- paintings, and sculptures. They were ists. Never before have so many of his proud of the architectural splendor best works been shown together in the of Florence and saw it as a sign of the United States. Antonio Quattrone/Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence city’s manifest destiny. This attitude Among the works on view is Don- was given voice by Leonardo Bruni, atello’s large sculpture of the Old Tes- who wrote around 1403–1404 in his tament prophet Habakkuk. “Speak, Panegyric to the City of Florence: damn you, speak!” Donatello, we are told, repeatedly shouted at the statue As soon as [visitors] have seen . -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Nanni Di Banco and Donatello: a Comparison Paolo Vaccarino

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 22 | Issue 4 Article 7 1952 Nanni di Banco and Donatello: A Comparison Paolo Vaccarino Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Vaccarino, Paolo. "Nanni di Banco and Donatello: A Comparison." New Mexico Quarterly 22, 4 (1952). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq/vol22/iss4/7 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r ," ~' Vaccarino: Nanni di Banco and Donatello: A Comparison II l. Paolo VaccaTino NANNI DI BANCO AND I DONATELLO: A COMPARISON 1 <. From the Foreword THE REI S a gap in our knowledge which no scholar has ever tried to fill. It is a gap which owes to the lack ofreal attention paid to the work of Nanni di Banco. To fill it is important not only be came of the fact of his amazing artistry, but because the lack of true familiarity with Nanni and his accomplishments has left a hole where a key should be in our knowledge of Renaissan~e art. The art history of the period has inevitably been somewhat in comprehensible, somewhere lacking in logical development. Without the key figure of Nanni, one is at a loss to explain the development of Donatello on one side and Luca della Robbia on the other; or to fill the gap between Giotto and Masaccio, and trace the history of later painters. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

Tuscany's World Heritage Sites

15 MARCH 2013 CATERINA POMINI 4171 TUSCANY'S WORLD HERITAGE SITES As of 2011, Italy has 47 sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, making it the country with the greatest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Tuscany alone boasts six UNESCO sites, almost equalling the numbers of countries like Croatia, Finland and Norway. Tuscany enshrines 6 Unesco World Heritage Sites you should definitely consider when planning your Tuscany tour. Here is the list: 1) Florence. Everything that could be said about the historic centre of Florence has already been said. Art, history, territory, atmosphere, traditions, everybody loves this city depicted by many as the Cradle of the Renaissance. Florence attracts millions of tourists every year and has been declared a World Heritage Site due to the fact that it represents a masterpiece of human creative genius + other 4 selection criteria. 2) Piazza dei Miracoli, Pisa. It was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1987 and is basically a wide walled area, partially paved and partially covered by grass, dominated by 4 great religious buildings: the Duomo, the Leaning Tower, the Baptistry and the Camposanto. 3) San Gimignano has been a World Heritage Site since 1990 and is considered the emblem of medieval Tuscany. Its historic centre represents a masterpiece of human creative genius, it bears a unique testimony to Tuscan civilization and surely is an outstanding example of architectural ensemble, which illustrates significant stages in human history. 4) 40 kilometers away from San Gimignano stands Siena, the historical enemy of Florence. Throughout the centuries, the city's medieval appearance has been preserved and expansion took place outside the walls. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge

Libraries: Architecture and the Ordering of Knowledge English text of March 29, 2009, by J. Connors for “Biblioteche: l’architettura e l’ordinamento del sapere,” with Angela Dressen, in Il Rinascimento Italiano e l’Europa, vol. 6, Luoghi, spazi, architetture, ed. Donatella Calabi and Elena Svalduz, Treviso-Costabissara, 2010, pp. 199-228. All the texts describing ancient libraries had been rediscovered by the mid-Quattrocento. Humanists knew Greek and Roman libraries from the accounts in Strabo, Varro, Seneca, and especially Suetonius, himself a former prefect of the imperial libraries. From Pliny everyone knew that Asinius Pollio founded the first public library in Rome, fulfilling the unrealized wish of Juliuys Caesar ("Ingenia hominum rem publicam fecit," "He made men's talents public property"). From Suetonius it was known that Augustus founded two libraries, one in the Porticus Octaviae, and another, for Greek and Latin books, in the temple of Apollo on the Palatine, where the sculptural decoration included not only a colossal statue of Apollo but also portraits of celebrated writers. The texts spoke frequently of author portraits, and also of the wealth and splendor of ancient libraries. The presses for the papyrus rolls were made of ebony and cedar; the architectural order and the revetments of the rooms were of marble; the sculpture was of gilt bronze. Boethius added that libraries were adorned with ivory and glass, while Isidore mentioned gilt ceilings and restful green cipollino floors. Senecan disapproval of ostentatious libraries, of "studiosa luxuria," of piling up more books than one could ever read, gave way to admiration for magnificent libraries. -

Illustrations Ij

Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiii Illustrations ij Fig. 1. Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1015, Doors of St. Michael’s, Hildesheim, Germany. Fig. 2. Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1425, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Flo- rence. Fig. 3. Bernardo Rossellino, Facade of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 4. Bernardo Rossellino, Interior of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 5. Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495–98, Refectory of the Monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Fig. 6. Anonymous Pisan artist, Pisa Cross #15, late twelfth century, Museo Civico, Pisa. Fig. 7. Anonymous artist, Cross of San Damiano, late twelfth century, Basilica of Santa Chiara, Assisi. Fig. 8. Giotto di Bondone, Cruci‹xion, ca. 1305, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua. Fig. 9. Masaccio, Trinity Fresco, ca. 1427, Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Fig. 10. Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Altarpiece of St. Francis, 1235, Church of San Francesco, Pescia. Fig. 11. St. Francis Master, St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, early four- teenth century, Upper Church of San Francesco, Assisi. Fig. 12. Anonymous Florentine artist, Detail of the Misericordia Fresco from the Loggia del Bigallo, 1352, Council Chamber, Misericor- dia Palace, Florence. Fig. 13. Florentine artist (Francesco Rosselli?), “Della Catena” View of Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiv ILLUSTRATIONS Florence, 1470s, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Fig. 14. Present-day view of Florence from the Costa San Giorgio. Fig. 15. Nicola Pisano, Nativity Panel, 1260, Baptistery Pulpit, Baptis- tery, Pisa. Fig.