Kim Sang Woo Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering Florence in the Footsteps of Dante Alighieri: “Must-Sees”

1 JUNE 2021 MICHELLE 324 DISCOVERING FLORENCE IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF DANTE ALIGHIERI: “MUST-SEES” In 1265, one of the greatest poets of all time was born in Florence, Italy. Dante Alighieri has an incomparable legacy… After Dante, no other poet has ever reached the same level of respect, recognition, and fame. Not only did he transform the Italian language, but he also forever altered European literature. Among his works, “Divine Comedy,” is the most famous epic poem, continuing to inspire readers and writers to this day. So, how did Dante Alighieri become the father of the Italian language? Well, Dante’s writing was different from other prose at the time. Dante used “common” vernacular in his poetry, making it more simple for common people to understand. Moreover, Dante was deeply in love. When he was only nine years old, Dante experienced love at first sight, when he saw a young woman named “Beatrice.” His passion, devotion, and search for Beatrice formed a language understood by all - love. For centuries, Dante’s romanticism has not only lasted, but also grown. For those interested in discovering more about the mysteries of Dante Alighieri and his life in Florence , there are a handful of places you can visit. As you walk through the same streets Dante once walked, imagine the emotion he felt in his everlasting search of Beatrice. Put yourself in his shoes, as you explore the life of Dante in Florence, Italy. Consider visiting the following places: Casa di Dante Where it all began… Dante’s childhood home. Located right in the center of Florence, you can find the location of Dante’s birth and where he spent many years growing up. -

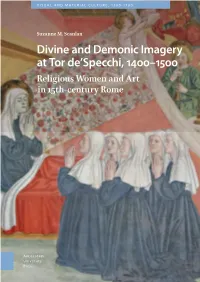

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Cellini Vs Michelangelo: a Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 22-30 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s).All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v6n2p4 Cellini vs Michelangelo: A Comparison of the Use of Furia, Forza, Difficultà, Terriblità, and Fantasia Maureen Maggio1 Abstract: Although a contemporary of the great Michelangelo, Benvenuto Cellini is not as well known to the general public today. Cellini, a master sculptor and goldsmith in his own right, made no secret of his admiration for Michelangelo’s work, and wrote treatises on artistic principles. In fact, Cellini’s artistic treatises can be argued to have exemplified the principles that Vasari and his contemporaries have attributed to Michelangelo. This paper provides an overview of the key Renaissance artistic principles of furia, forza, difficultà, terriblità, and fantasia, and uses them to examine and compare Cellini’s famous Perseus and Medusa in the Loggia deiLanzi to the work of Michelangelo, particularly his famous statue of David, displayed in the Galleria dell’ Accademia. Using these principles, this analysis shows that Cellini not only knew of the artistic principles of Michelangelo, but that his work also displays a mastery of these principles equal to Michelangelo’s masterpieces. Keywords: Cellini, Michelangelo, Renaissance aesthetics, Renaissance Sculptors, Italian Renaissance 1.0Introduction Benvenuto Cellini was a Florentine master sculptor and goldsmith who was a contemporary of the great Michelangelo (Fenton, 2010). Cellini had been educated at the Accademiade lDisegno where Michelangelo’s artistic principles were being taught (Jack, 1976). -

Leonardo Bruni, the Medici, and the Florentine Histories1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace /HRQDUGR%UXQLWKH0HGLFLDQGWKH)ORUHQWLQH+LVWRULHV *DU\,DQ]LWL Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 69, Number 1, January 2008, pp. 1-22 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\8QLYHUVLW\RI3HQQV\OYDQLD3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/jhi.2008.0009 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jhi/summary/v069/69.1ianziti.html Access provided by University of Queensland (30 Oct 2015 04:56 GMT) Leonardo Bruni, the Medici, and the Florentine Histories1 Gary Ianziti Leonardo Bruni’s relationship to the Medici regime raises some intriguing questions. Born in 1370, Bruni was Chancellor of Florence in 1434, when Cosimo de’ Medici and his adherents returned from exile, banished their opponents, and seized control of government.2 Bruni never made known his personal feelings about this sudden regime change. His memoirs and private correspondence are curiously silent on the issue.3 Yet it must have been a painful time for him. Among those banished by the Medici were many of his long-time friends and supporters: men like Palla di Nofri Strozzi, or Rinaldo degli Albizzi. Others, like the prominent humanist and anti-Medicean agita- tor Francesco Filelfo, would soon join the first wave of exiles.4 1 This study was completed in late 2006/early 2007, prior to the appearance of volume three of the Hankins edition and translation of Bruni’s History of the Florentine People (see footnote 19). References to books nine to twelve of the History are consequently based on the Santini edition, cited in footnote 52. -

Sources of Donatello's Pulpits in San Lorenzo Revival and Freedom of Choice in the Early Renaissance*

! " #$ % ! &'()*+',)+"- )'+./.#')+.012 3 3 %! ! 34http://www.jstor.org/stable/3047811 ! +565.67552+*+5 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE SOURCES OF DONATELLO'S PULPITS IN SAN LORENZO REVIVAL AND FREEDOM OF CHOICE IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE* IRVING LAVIN HE bronze pulpits executed by Donatello for the church of San Lorenzo in Florence T confront the investigator with something of a paradox.1 They stand today on either side of Brunelleschi's nave in the last bay toward the crossing.• The one on the left side (facing the altar, see text fig.) contains six scenes of Christ's earthly Passion, from the Agony in the Garden through the Entombment (Fig. -

Sponsor-A-Michelangelo Works Are Reserved in the Order That Gifts Are Received

Sponsor-A-Michelangelo Works are reserved in the order that gifts are received. Please call 615.744.3341 to make your selection. Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane, Masterpiece Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti October 30, 2015–January 6, 2016 Michelangelo Buonarroti. Man with Crested Helmet, ca. 1504. Pen and ink, 75 Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for a x 56 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. Draped Figure, ca. 1506. Pen and ink over 59F black chalk, 297 x 197 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 39F Sponsored by: Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the Leg of the Christ Child in the “Doni Sponsored by: Tondo,” ca. 1506. Pen and ink, 163 x 92 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 23F Sponsored by: Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the Apostles in the Transfiguration (Three Nudes), ca. 1532. Black chalk, pen and Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the ink. 178 x 209 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for Christ Head of the Madonna in the “Doni Florence, inv. 38F Tondo,” ca. 1506. Red chalk, 200 x 172 in Limbo, ca. 1532–33. Red chalk over black chalk. 163 x 149 mm. Casa mm. Casa Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 1F Sponsored by: Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 35F Reserved Sponsored by: Sponsored by: Patricia and Rodes Hart Michelangelo Buonarroti. The Sacrifice of Isaac, ca. 1535. Black chalk, red chalk, pen and ink. 482 x 298 mm. Casa Michelangelo Buonarroti. Studies of a Horse, ca. 1540. Black chalk, traces of red Michelangelo Buonarroti. Study for the Buonarroti, Florence, inv. 70F chalk. 403 x 257 mm. Casa Buonarroti, Risen Christ, ca. 1532. Black chalk. 331 x 198 mm. -

Allestimenti Di Ritratti E Narrative Storico Genealogiche Nei Palazzi Fiorentini, Ca

COLLANA ALTI STUDI SULL’ETÀ E LA CULTURA DEL BAROCCO PASQUALE FOCARILE Allestimenti di ritratti e narrative storico genealogiche nei palazzi fiorentini, ca. 1650-1750 COLLANA ALTI STUDI SULL’ETÀ E LA CULTURA DEL BAROCCO V - IL RITRATTO Fondazione 1563 per l’Arte e la Cultura della Compagnia di San Paolo Sede legale: Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 75 – 10128 Torino Sede operativa: Piazza Bernini, 5 – 10138 Torino Tel. 011 4401401 – Fax 011 4401450 – [email protected] Codice fiscale: 97520600012 Consiglio di Amministrazione 2018-2020: Piero Gastaldo (Presidente), Walter Barberis (Vicepresidente) Consiglieri: Allegra Alacevich, Laura Barile, Blythe Alice Raviola Direttore scientifico del Programma Barocco: Michela di Macco Direttore: Anna Cantaluppi Vicedirettore: Elisabetta Ballaira Consiglio di Amministrazione 2015-2017: Rosaria Cigliano (Presidente), Michela di Macco (Vicepresidente) Consiglieri: Allegra Alacevich, Walter Barberis, Stefano Pannier Suffait Direttore: Anna Cantaluppi Responsabile culturale: Elisabetta Ballaira Programma di Studi sull’Età e la Cultura del Barocco Borse di Alti Studi 2017 Tema del Bando 2017: Il Ritratto (1680-1750) Assegnatari: Chiara Carpentieri, Pasquale Focarile, Ludovic Jouvet, Fleur Marcais, Pietro Riga, Augusto Russo Tutor dei progetti di ricerca: Cristiano Giometti, Cinzia M. Sicca, Lucia Simonato, Alain Schnapp, Beatrice Alfonzetti, Francesco Caglioti Cura editoriale: Alice Agrillo È vietata la riproduzione, anche parziale e con qualsiasi mezzo effettuata, non autorizzata. L’Editore si scusa per -

Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D

Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal Vol. 11, No. 1 • Fall 2016 The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence Mary D. Garrard eminist scholars have effectively unmasked the misogynist messages of the Fstatues that occupy and patrol the main public square of Florence — most conspicuously, Benvenuto Cellini’s Perseus Slaying Medusa and Giovanni da Bologna’s Rape of a Sabine Woman (Figs. 1, 20). In groundbreaking essays on those statues, Yael Even and Margaret Carroll brought to light the absolutist patriarchal control that was expressed through images of sexual violence.1 The purpose of art, in this way of thinking, was to bolster power by demonstrating its effect. Discussing Cellini’s brutal representation of the decapitated Medusa, Even connected the artist’s gratuitous inclusion of the dismembered body with his psychosexual concerns, and the display of Medusa’s gory head with a terrifying female archetype that is now seen to be under masculine control. Indeed, Cellini’s need to restage the patriarchal execution might be said to express a subconscious response to threat from the female, which he met through psychological reversal, by converting the dangerous female chimera into a feminine victim.2 1 Yael Even, “The Loggia dei Lanzi: A Showcase of Female Subjugation,” and Margaret D. Carroll, “The Erotics of Absolutism: Rubens and the Mystification of Sexual Violence,” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, ed. Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 127–37, 139–59; and Geraldine A. Johnson, “Idol or Ideal? The Power and Potency of Female Public Sculpture,” Picturing Women in Renaissance and Baroque Italy, ed. -

Insider's Florence

Insider’s Florence Explore the birthplace of the Renaissance November 8 - 15, 2014 Book Today! SmithsonianJourneys.org • 1.877.338.8687 Insider’s Florence Overview Florence is a wealth of Renaissance treasures, yet many of its riches elude all but the most experienced travelers. During this exclusive tour, Smithsonian Journey’s Resident Expert and popular art historian Elaine Ruffolo takes you behind the scenes to discover the city’s hidden gems. You’ll enjoy special access at some of Florence’s most celebrated sites during private after-hours visits and gain insight from local experts, curators, and museum directors. Learn about restoration issues with a conservator in the Uffizi’s lab, take tea with a principessa after a private viewing of her art collection, and meet with artisans practicing their ages-old art forms. During a special day in the countryside, you’ll also go behind the scenes to explore lovely villas and gardens once owned by members of the Medici family. Plus, enjoy time on your own to explore the city’s remarkable piazzas, restaurants, and other museums. This distinctive journey offers first time and returning visitors a chance to delve deeper into the arts and treasures of Florence. Smithsonian Expert Elaine Ruffolo November 8 - 15, 2014 For popular leader Elaine Ruffolo, Florence offers boundless opportunities to study and share the finest artistic achievements of the Renaissance. Having made her home in this splendid city, she serves as Resident Director for the Smithsonian’s popular Florence programs. She holds a Master’s degree in art history from Syracuse University and serves as a lecturer and field trip coordinator for the Syracuse University’s program in Italy. -

View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

PRESENT IN THE PERFORMANCE: STEFANO MADERNO’S SANTA CECILIA AND THE FRAME OF THE JUBILEE OF 1600 by KELLY ANNE WHITFORD A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kelly Anne Whitford Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Dr. James Harper Chairperson Dr. Nicola Camerlenghi Member Dr. Jessica Maier Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2011 ii © 2011 Kelly Anne Whitford iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kelly Anne Whitford Master of Arts Department of Art History December 2011 Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 In 1599, in commemoration of the remarkable discovery of the incorrupt remains of the early Christian martyr St. Cecilia, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrato commissioned Stefano Maderno to create a memorial sculpture which dramatically departed from earlier and contemporary monuments. While previous scholars have considered the influence of the historical setting on the conception of Maderno’s Santa Cecilia, none have studied how this historical moment affected the beholder of the work. In 1600, the Church’s Holy Year of Jubilee drew hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to Rome to take part in Church rites and rituals. -

The Press Release

Williamsburg, Muscarelle Museum of Art, February 6 –April 14, 2013 Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, April 21--June 30, 2013 For Immediate Release 21 September 2012 To download images, please go to: http://www.wm.edu/muscarelle/michelangelopress.html MEDIA CONTACT: Betsy Moss for Muscarelle Museum of Art Phone: 804.355.1557 E-mail: [email protected] MICHELANGELO SCHOLAR AT MUSCARELLE MUSEUM TO ANNOUNCE MAJOR DRAWINGS SHOW PINA RAGIONIERI, DIRECTOR OF CASA BUONAROTTI, WILL GIVE ILLUSTRATED LECTURE OF MASTERPIECE DRAWINGS BY MICHELANGELO Twenty-six drawings in all media make Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane the most important Michelangelo show seen in the USA in decades. The Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William & Mary announced today that renowned Michelangelo scholar, Pina Ragionieri, will speak at the museum at 6:00 PM on September 25, 2012, to describe and illustrate the twenty-six original drawings by Michelangelo that will be in the major international exhibition, Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane Masterpiece Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti, opening February 9, 2013. The landmark exhibition is being organized in honor of the thirtieth anniversary of the foundation of the Muscarelle Museum of Art in 1983. Dr Pina Ragionieri, director of the Casa Buonarroti museum in Florence, will also attend the opening ceremonies and will be honored for her contributions to the studies of the great master. “I greatly look forward to this opportunity to display the treasures of the Casa Buonarroti at the Muscarelle Museum at the College of William & Mary,” she said. “International exhibitions introduce our museum not only to the specialists, but also to a broader public overseas.” Michelangelo: Sacred and Profane Masterpiece Drawings from the Casa Buonarroti, follows on the success of the 2010 exhibition at the Muscarelle, Michelangelo: Anatomy as Architecture, Drawings by the Master.