Picturing Mary: Woman, Mother, Idea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Worship Plan for Tuesday, December 24, 2019

SOLOMON'S EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH 4856 WAYNE ROAD CHAMBERSBURG, PA 17202 (717) 267-2266 EMAIL: [email protected] WEB SITE: www.solomonslutheran.org FACEBOOK SEARCH: Solomon’s Lutheran Facebook "Solomon's Evangelical Lutheran Church, following the example of Jesus Christ, seeks to live in the confidence and fullness of God's grace; to preach the Good News boldly and truthfully; to support and serve others in faith; to work in harmony with all creation." NATIVITY OF OUR LORD / CHRISTMAS EVE DECEMBER 24, 2020 DECEMBER 24, 2020 NATIVITY OF OUR LORD I: CHRISTMAS EVE In winter’s deepest night, we welcome the light of the Christ child. Isaiah declares that the light of the long-promised king will illumine the world and bring endless peace and justice. Paul reminds us that the grace of God through Jesus Christ brings salvation to all people. The angels declare that Jesus’ birth is good and joyful news for everyone, including lowly shepherds. Filled with the light that shines in our lives, we go forth to share the light of Christ with the whole world. PRELUDE GREETINGS AND ANNOUNCEMENTS CONFESSION AND FORGIVENESS Blessed be the holy Trinity, ☩ one God, Love from the beginning, Word made flesh, Breath of heaven. Amen. Let us confess our sinfulness before God and one another, trusting in God’s endless mercy and love. Merciful God, we confess that we are not perfect. We have said and done things we regret. We have tried to earn your redeeming grace, while denying it to others. We have resisted your call to be your voice in the world. -

SELF-FLAGELLATION in the EARLY MODERN ERA Patrick

SELF-FLAGELLATION IN THE EARLY MODERN ERA Patrick Vandermeersch Self-fl agellation is often understood as self-punishment. History teaches us, however, that the same physical act has taken various psychologi- cal meanings. As a mass movement in the fourteenth century, it was primarily seen as an act of protest whereby the fl agellants rejected the spiritual authority and sacramental power of the clergy. In the sixteenth century, fl agellation came to be associated with self-control, and a new term was coined in order to designate it: ‘discipline’. Curiously, in some religious orders this shift was accompanied by a change in focus: rather than the shoulders or back, the buttocks were to be whipped instead. A great controversy immediately arose but was silenced when the possible sexual meaning of fl agellation was realized – or should we say, constructed? My hypothesis is that the change in both the name and the way fl agellation was performed indicates the emergence of a new type of modern subjectivity. I will suggest, furthermore, that this requires a further elaboration of Norbert Elias’s theory of the ‘civiliz- ing process’. A Brief Overview of the History of Flagellation1 Let us start with the origins of religious self-fl agellation. Although there were many ascetic practices in the monasteries at the time of the desert fathers, self-fl agellation does not seem to have been among them. With- out doubt many extraordinary rituals were performed. Extreme degrees 1 The following historical account summarizes the more detailed historical research presented in my La chair de la passion. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-72855-3 - The Cambridge Companion to Giovanni Bellini Edited by Peter Humfrey Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to giovanni bellini Giovanni Bellini was the dominant painter of Early Renaissance Venice and is today recognized as one of the greatest of all Italian Renaissance artists. Although he has been the subject of numerous scholarly studies, his art continues to pose intriguing problems. This volume brings together com- missioned essays that focus on important topics and themes in Bellini’s ca- reer. They include a consideration of Bellini’s position in the social and professional life of early modern Venice; reassessments of his artistic rela- tionships with his brother-in-law Mantegna, with Flemish painting, and with the “modern style’’ that emerged in Italy around 1500; and explorations of Bellini’s approaches to sculpture and architecture, and to landscape and color, elements that have always been recognized as central to his pictorial genius. The volume concludes with analyses of Bellini’s constantly evolving pictorial technique and the procedures of his busy workshop. Peter Humfrey is Professor of Art History at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of several books on painting in Renaissance Venice and the Veneto, including Cima da Conegliano, The Altarpiece in Renaissance Venice, and Lorenzo Lotto; and is coauthor of the catalogues for two major loan exhibitions, Lorenzo Lotto: Rediscovered Master of the Renaissance and Dosso Dossi: Court Painter of Renaissance -

The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 46

University of Dayton eCommons The Marian Philatelist Marian Library Special Collections 1-1-1970 The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 46 A. S. Horn W. J. Hoffman Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist Recommended Citation Horn, A. S. and Hoffman, W. J., "The Marian Philatelist, Whole No. 46" (1970). The Marian Philatelist. 46. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/imri_marian_philatelist/46 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Special Collections at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Marian Philatelist by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. &fie Marian Philatelist PUBLISHED BY THE MARIAN PHILATELIC STUDY GROUP Business Address: Rev. A. S. Horn Chairman 424 West Crystal View Avenue W^J. Hoffman Editor Orange, California 92667, U.S.A. Vol. 8 No. 1 Whole No. 46 JANUARY 1, 1970 New Year's Greetings to all our members. Thanks to the assistance of one of our members we are able, at least temporarily, to continue the publication of THE MARIAN PHILATELIST. In the name of all our members I wish to thank Mr. Hoffman for his con stant devotion to the study of the Blessed Virgin on stamps. His unselfish contribu tion in time and effort has made the continuation of our paper possible. May God bless you. Father Horn NEW ISSUES ANGUILLA: The philatelic press indicated that a 4-stamp Christmas set would be issu ed, and gave designs and values as listed on page 65 of the November 1969 issue. -

Michelangelo's Pieta in Bronze

Michelangelo’s Pieta in Bronze by Michael Riddick Fig. 1: A bronze Pieta pax, attributed here to Jacopo and/or Ludovico del Duca, ca. 1580 (private collection) MICHELANGELO’S PIETA IN BRONZE The small bronze Pieta relief cast integrally with its frame for use as a pax (Fig. 1) follows after a prototype by Michelangelo (1475-1564) made during the early Fig. 2: A sketch (graphite and watercolor) of the Pieta, 1540s. Michelangelo created the Pieta for Vittoria attributed to Marcello Venusti, after Michelangelo Colonna (1492-1547),1 an esteemed noblewoman with (© Teylers Museum; Inv. A90) whom he shared corresponding spiritual beliefs inspired by progressive Christian reformists. Michelangelo’s Pieta relates to Colonna’s Lamentation on the Passion of Pieta was likely inspired by Colonna’s writing, evidenced Christ,2 written in the early 1540s and later published in through the synchronicity of his design in relationship 3 1556. In her Lamentation Colonna vividly adopts the role with Colonna’s prose. of Mary in grieving the death of her son. Michelangelo’s Michelangelo’s Pieta in Bronze 2 Michael Riddick Fig. 3: An incomplete marble relief of the Pieta, after Michelangelo (left; Vatican); a marble relief of the Pieta, after Michelangelo, ca. 1551 (right, Santo Spirito in Sassia) Michelangelo’s original Pieta for Colonna is a debated Agostino Carracci (1557-1602) in 1579.5 By the mid-16th subject. Traditional scholarship suggests a sketch at century Michelangelo’s Pieta for Colonna was widely the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is the original celebrated and diffused through prints as well as painted he made for her while others propose a panel painting and sketched copies. -

Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti Devozionali E “Quadretti Da Letto” Di Una Virtuosa Del Pennello

Temporary exhibition from the storage. LISABETTA E IRANI DipintiS devozionali e “quadretti da letto” di una virtuosa del pennello Palazzo Pepoli Campogrande 18 september - 25 november 2018 Elisabetta Sirani Dipinti devozionali e “quadretti da letto” di una virtuosa del pennello The concept of the exhibition is linked to an important recovery realized by the Nucleo Carabinieri Tutela Patrimonio Culturale of Bologna: the finding on the antique market, thanks to the advisory of the Pinacoteca, of a small painting with a Virgin praying attributed to the well-known Bolognese painter Elisabetta Sirani (Bologna 1638-1665), whose disappearance has been denounced by Enrico Mauceri in 1930. The restitution of the work to the Pinacoteca and its presentation to the public is accompanied by an exposition of some paintings of Elisabetta, usually kept into the museum storage, with the others normally showed in the gallery (Saint Anthony of Padua adoring Christ Child) and in Palazzo Pepoli Elisabetta Sirani, Virgin praying, Campogrande (Saint Mary Magdalene and Saint Jerome). canvas, cm 46x36, Inv. 625 The aim of this intimate exhibition is to ce- lebrate Elisabetta Sirani as one of the most representative personalities of the Bolognese School in the XVII century, who followed the artistic lesson of the divine Guido Reni. Actually, Elisabetta was not directly a student of Reni, who died when she was four years old. First of four kids, she learnt from her father Giovanni Andrea Sirani, who was direct student of Guido. We can imagine how much the collection of Reni’s drawings kept by Giovanni inspired our young painter, who started to practise in a short while. -

Wish You Happy Feast of Epiphany

WISH YOU HAPPY FEAST OF EPIPHANY Receiving than Giving: The most foundational truth of the Christian life can be located in today’s gospel of the Epiphany. when we focus on the wise men, the theme of the gospel is about searching, finding, and the giving of gifts. These themes, however, are not the deepest truth of today’s feast. To find that truth we must not look at what the wise men do, but at what Jesus does. And what does Jesus do? He receives the gifts that the wise men offer. This action is arguably the first action of Jesus ever recorded in the gospels: to accept the gifts that are given. Our faith is not primarily about what we do, but rather about what God does. God has made us and saved us. God’s actions are the actions that are at the heart of the gospel. Being a Christian is not about what we do, but what we accept; it is not about giving but about receiving. So what is it that we are called to receive? The three gifts help here—gold, frankincense, myrrh—value, mystery, pain. The first gift is the gift of gold, a gift of great value and worth. It points to the value and worth of our own lives. We are persons of great worth. God has made us so. God has instilled in us a dignity that is a part of who we are. That dignity is nothing we can earn and nothing that we can lose by failure or sin. -

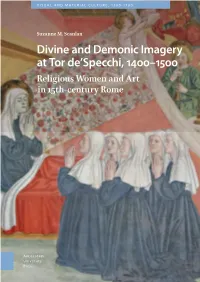

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

ELISABETTA SIRANI's JUDITH with the HEAD of HOLOFERNES By

ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI (Under the Direction of Shelley Zuraw) ABSTRACT This thesis examines the life and artistic career of the female artist, Elisabetta Sirani. The paper focuses on her unparalleled depictions of heroines, especially her Judith with the Head of Holofernes. By tracing the iconography of Judith from masters of the Renaissance into the mid- seventeenth century, it is evident that Elisabetta’s painting from 1658 is unique as it portrays Judith in her ultimate triumph. Furthermore, an emphasis is placed on the relationship between Elisabetta’s Judith and three of Guido Reni’s Judith images in terms of their visual resemblances, as well as their symbolic similarities through the incorporation of a starry sky and crescent moon. INDEX WORDS: Elisabetta Sirani, Judith, Holofernes, heroines, Timoclea, Giovanni Andrea Sirani, Guido Reni, female artists, Italian Baroque, Bologna ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI B.A., Florida State University, 2003 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2008 © 2008 Jessica Cole Rubinski All Rights Reserved ELISABETTA SIRANI’S JUDITH WITH THE HEAD OF HOLOFERNES by JESSICA COLE RUBINSKI Major Professor: Dr. Shelley Zuraw Committee: Dr. Isabelle Wallace Dr. Asen Kirin Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2008 iv To my Family especially To my Mother, Pamela v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank Robert Henson of Carolina Day School for introducing me to the study of Art History, and the professors at Florida State University for continuing to spark my interest and curiosity for the subject. -

Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

STATE STATUTES Current Through March 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE Defining child abuse or Definitions of Child neglect in State law Abuse and Neglect Standards for reporting Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal Persons responsible for the child and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal Exceptions statutes. This publication presents civil definitions that determine the grounds for intervention by Summaries of State laws State child protective agencies.1 At the Federal level, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment To find statute information for a Act (CAPTA) has defined child abuse and neglect particular State, as "any recent act or failure to act on the part go to of a parent or caregiver that results in death, https://www.childwelfare. serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, gov/topics/systemwide/ or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that laws-policies/state/. presents an imminent risk of serious harm."2 1 States also may define child abuse and neglect in criminal statutes. These definitions provide the grounds for the arrest and prosecution of the offenders. 2 CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320), 42 U.S.C. § 5101, Note (§ 3). Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov CAPTA defines sexual abuse as follows: and neglect in statute.5 States recognize the different types of abuse in their definitions, including physical abuse, The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. -

The Pietà in Historical Perspective

The Pietà in historical perspective The Pietà is not a scene that can be found in the Gospels. The Gospels describe Crucifixion (El Greco), Deposition or descent from the Cross (Rubens), Laying on the ground (Epitaphios), Lamentation (Giotto), Entombment (Rogier Van de Weyden) So How did this image emerge? Background one-devotional images • Narrative images from the Gospel, e.g Icon of Mary at foot of cross • Devotional images, where scene is taken out of its historical context to be used for prayer. e.g. Man of Sorrows from Constantinople and print of it by Israhel van Meckenhem. The Pietà is one of a number of devotional images that developed from the 13th century, which went with intense forms of prayer in which the person was asked to imagine themselves before the image speaking with Jesus. It emerged first in the Thuringia area of Germany, where there was a tradition of fine wood carving and which was also open to mysticism. Background two-the position of the Virgin Mary • During the middle ages the position of Mary grew in importance, as reflected in the doctrine of the Assumption (Titian), the image of the coronation of the Virgin (El Greco) • So too did the emphasis on Mary sharing in the suffering of Jesus as in this Mater Dolorosa (Titian) • Further background is provided by the Orthodox image of the threnos which was taken up by Western mystics, and the image of The Virgin of Humility A devotional gap? • So the Pietà, which is not a Gospel scene, started to appear as a natural stage, between the Gospel scenes of the crucifixion smf the deposition or descent from the cross on the one hand, and the stone of annointing, the lamentation, and the burial on the other. -

Donatello's Terracotta Louvre Madonna

Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sandra E. Russell May 2015 © 2015 Sandra E. Russell. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning by SANDRA E. RUSSELL has been approved for the School of Art + Design and the College of Fine Arts by Marilyn Bradshaw Professor of Art History Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract RUSSELL, SANDRA E., M.A., May 2015, Art History Donatello’s Terracotta Louvre Madonna: A Consideration of Structure and Meaning Director of Thesis: Marilyn Bradshaw A large relief at the Musée du Louvre, Paris (R.F. 353), is one of several examples of the Madonna and Child in terracotta now widely accepted as by Donatello (c. 1386-1466). A medium commonly used in antiquity, terracotta fell out of favor until the Quattrocento, when central Italian artists became reacquainted with it. Terracotta was cheap and versatile, and sculptors discovered that it was useful for a range of purposes, including modeling larger works, making life casts, and molding. Reliefs of the half- length image of the Madonna and Child became a particularly popular theme in terracotta, suitable for domestic use or installation in small chapels. Donatello’s Louvre Madonna presents this theme in a variation unusual in both its form and its approach. In order to better understand the structure and the meaning of this work, I undertook to make some clay works similar to or suggestive of it.