Antonello Da Messina's Dead Christ Supported by Angels in the Prado

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-72855-3 - The Cambridge Companion to Giovanni Bellini Edited by Peter Humfrey Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to giovanni bellini Giovanni Bellini was the dominant painter of Early Renaissance Venice and is today recognized as one of the greatest of all Italian Renaissance artists. Although he has been the subject of numerous scholarly studies, his art continues to pose intriguing problems. This volume brings together com- missioned essays that focus on important topics and themes in Bellini’s ca- reer. They include a consideration of Bellini’s position in the social and professional life of early modern Venice; reassessments of his artistic rela- tionships with his brother-in-law Mantegna, with Flemish painting, and with the “modern style’’ that emerged in Italy around 1500; and explorations of Bellini’s approaches to sculpture and architecture, and to landscape and color, elements that have always been recognized as central to his pictorial genius. The volume concludes with analyses of Bellini’s constantly evolving pictorial technique and the procedures of his busy workshop. Peter Humfrey is Professor of Art History at the University of St Andrews. He is the author of several books on painting in Renaissance Venice and the Veneto, including Cima da Conegliano, The Altarpiece in Renaissance Venice, and Lorenzo Lotto; and is coauthor of the catalogues for two major loan exhibitions, Lorenzo Lotto: Rediscovered Master of the Renaissance and Dosso Dossi: Court Painter of Renaissance -

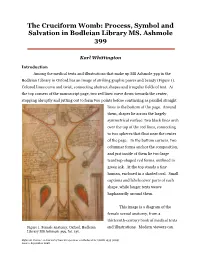

The Cruciform Womb: Process, Symbol and Salvation in Bodleian Library MS

The Cruciform Womb: Process, Symbol and Salvation in Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 399 Karl Whittington Introduction Among the medical texts and illustrations that make up MS Ashmole 399 in the Bodleian Library in Oxford lies an image of striking graphic power and beauty (Figure 1). Colored lines curve and twist, connecting abstract shapes and irregular fields of text. At the top corners of the manuscript page, two red lines curve down towards the center, stopping abruptly and jutting out to form two points before continuing as parallel straight lines to the bottom of the page. Around them, shapes lie across the largely symmetrical surface: two black lines arch over the top of the red lines, connecting to two spheres that float near the center of the page. In the bottom corners, two columnar forms anchor the composition, and just inside of them lie two large teardrop-shaped red forms, outlined in green ink. At the top stands a tiny human, enclosed in a shaded oval. Small captions and labels cover parts of each shape, while longer texts weave haphazardly around them. This image is a diagram of the female sexual anatomy, from a thirteenth-century book of medical texts Figure 1. Female anatomy, Oxford, Bodleian and illustrations. Modern viewers can Library MS Ashmole 399, fol. 13v. Different Visions: A Journal of New Perspectives on Medieval Art (ISSN 1935-5009) Issue 1, September 2008 Whittington– The Cruciform Womb: Process, Symbol and Salvation in Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 399 decipher easily only a few of these forms: to us, the drawing resembles some kind of map or abstract diagram more than a representation of actual anatomy, or anything else recognizable, for that matter. -

Rdna Fingerprinting As a Tool in Epidemiological Analysis of Salmonella Typhi Infections

Epidemiol. Infect. (1991), 107, 565-576 565 Printed in Great Britain rDNA fingerprinting as a tool in epidemiological analysis of Salmonella typhi infections A. NASTAS1, C. MAMMINA AND M. R. VILLAFRATE Department of Hygiene & Microbiology 'G. D'Alessandro', Center for Enterobacteriaceae of Southern Italy, University of Palermo, via del Vespro 133, 90127 Palermo, Italy (Accepted 11 July 1991) SUMMARY Characterization of 169 strains of Salmonella typhi of phage types C1; C4, D1 and D9 isolated in 1975-88 was carried out by rDNA gene restriction pattern analysis. Twenty-four isolates had been recovered during four large waterbone outbreaks in the last 20 years in Sicily; 145 strains, isolated from apparently sporadic cases of infection in Southern Italy in the same period of time, were also examined. Application of rRNA-DNA hybridization technique after digestion of chromo- somal DNA with Cla I showed the identity of patterns of the epidemic strains of phage types C1 and D1; confirming attribution of the outbreaks to single bacterial clones. Patterns of the two available strains of lysotype D9 were slightly different, whilst the 12 epidemic strains of phage type C4 could be assigned to two distinct patterns scarcely related to each other and, consequently, to two different clones. A considerable heterogeneity was detected among all apparently sporadic isolates of the four phage types under study. This fingerprinting method appears a reliable tool to complement phage typing in characterizing isolates of S. typhi. In particular, epidemiological features of spread of this salmonella serovar in areas, where simultaneous circulation of indigenous and imported strains occurs, can be elucidated. -

I Speak As One in Doubt

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses August 2019 I Speak as One in Doubt Margaret Hazel Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons, and the Sculpture Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Margaret Hazel, "I Speak as One in Doubt" (2019). Masters Theses. 807. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/807 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I Speak as One in Doubt. A Thesis Presented by Margaret Hazel Wilson Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS May 2019 Department of Art I Speak as One in Doubt. A Thesis Presented by MARGARET HAZEL WILSON Approved as to style and content by: _____________________________ Alexis Kuhr, Chair _____________________________ Jenny Vogel, Member _____________________________ Robin Mandel, Member _____________________________ Sonja Drimmer, Member ______________________________ Young Min Moon, Graduate Program Director Department of Art ________________________________ Shona MacDonald, Department Chair Department of Art DEDICATION To my mom, who taught me to tell meandering stories, and that learning, and changing, is something to love. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to offer my heartfelt thanks to my committee members for their generous dialogue in the course of this thesis, especially my chair, Alexis Kuhr, for her excellent listening ear. -

Rethinking Savoldo's Magdalenes

Rethinking Savoldo’s Magdalenes: A “Muddle of the Maries”?1 Charlotte Nichols The luminously veiled women in Giovanni Gerolamo Savoldo’s four Magdalene paintings—one of which resides at the Getty Museum—have consistently been identified by scholars as Mary Magdalene near Christ’s tomb on Easter morning. Yet these physically and emotionally self- contained figures are atypical representations of her in the early Cinquecento, when she is most often seen either as an exuberant observer of the Resurrection in scenes of the Noli me tangere or as a worldly penitent in half-length. A reconsideration of the pictures in connection with myriad early Christian, Byzantine, and Italian accounts of the Passion and devotional imagery suggests that Savoldo responded in an inventive way to a millennium-old discussion about the roles of the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene as the first witnesses of the risen Christ. The design, color, and positioning of the veil, which dominates the painted surface of the respective Magdalenes, encode layers of meaning explicated by textual and visual comparison; taken together they allow an alternate Marian interpretation of the presumed Magdalene figure’s biblical identity. At the expense of iconic clarity, the painter whom Giorgio Vasari described as “capriccioso e sofistico” appears to have created a multivalent image precisely in order to communicate the conflicting accounts in sacred and hagiographic texts, as well as the intellectual appeal of deliberately ambiguous, at times aporetic subject matter to northern Italian patrons in the sixteenth century.2 The Magdalenes: description, provenance, and subject The format of Savoldo’s Magdalenes is arresting, dominated by a silken waterfall of fabric that communicates both protective enclosure and luxuriant tactility (Figs. -

Adriatic Odyssey

confluence of historic cultures. Under the billowing sails of this luxurious classical archaeologist who is a curator of Greek and Roman art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Starting in the lustrous canals of Venice, journey to Ravenna, former capital of the Western Roman Empire, to admire the 5th- and 6th-century mosaics of its early Christian churches and the elegant Mausoleum of Galla Placidia. Across the Adriatic in the former Roman province of Dalmatia, call at Split, Croatia, to explore the ruined 4th-century palace of the emperor Diocletian. Sail to the stunning walled city of Dubrovnik, where a highlight will be an exclusive concert in a 16th-century palace. Spartan town of Taranto, home to the exceptional National Archaeological Museum. Nearby, in the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Alberobello, discover hundreds of dome-shaped limestone dwellings called Spend a delightful day at sea and call in Reggio Calabria, where you will behold the 5th-century-B.C. , heroic nude statues of Greek warriors found in the sea nearly 50 years ago. After cruising the Strait of Messina, conclude in Palermo, Sicily, where you can stroll amid its UNESCO-listed Arab-Norman architecture on an optional postlude. On previous Adriatic tours aboard , cabins filled beautiful, richly historic coastlines. At the time of publication, the world Scott Gerloff for real-time information on how we’re working to keep you safe and healthy. You’re invited to savor the pleasures of Sicily by extending your exciting Adriatic Odyssey you can also join the following voyage, “ ” from September 24 to October 2, 2021, and receive $2,500 Venice to Palermo Aboard Sea Cloud II per person off the combined fare for the two trips. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels Between English Poetry and the Visual Arts Roberta Aronson

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 1-1-2003 Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels between English Poetry and the Visual Arts Roberta Aronson Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Aronson, R. (2003). Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels between English Poetry and the Visual Arts (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/11 This Worldwide Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interart Studies from the Middle Ages to the Early Modern Era: Stylistic Parallels between English Poetry and the Visual Arts A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Roberta Chivers Aronson October 1, 2003 @Copyright by Roberta Chivers Aronson, 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to extend my appreciation to my many colleagues and family members whose collective support and inspiration underlie all that I do: • To my Provost, Dr. Ralph Pearson, for his kind professional encouragement, • To my Dean, Dr. Connie Ramirez, who creates a truly collegial and supportive academic environment, • To my Director, Dr. Albert C. Labriola, for his intellectual generosity and guidance; to Dr. Bernard Beranek for his enthusiasm and thoughtful conversation; and to Dr. -

Fra Tardogotico E Rinascimento: Messina Tra Sicilia E Il Continente

Artigrama, núm. 23, 2008, 301-326 — I.S.S.N.: 0213-1498 Fra Tardogotico e Rinascimento: Messina tra Sicilia e il continente FULVIA SCADUTO* Resumen L’architettura prodotta in ambito messinese fra Quattro e Cinquecento si è spesso prestata ad una valutazione di estraneità rispetto al contesto isolano. L’idea che Messina sia la città più toscana e rinascimentale del sud va probabilmente mitigata: i terremoti che hanno col- pito in modo devastante Messina e la Sicilia orientale hanno probabilmente sottratto numerose prove di una prolungata permanenza del gotico in quest’area condizionando inevitabilmente la lettura degli storici. Bisogna aggiungere che i palazzi di Taormina risultano erroneamente retrodatati e legati al primo Quattrocento. In realtà in questi episodi (ed altri, come quelli di palazzi di Cosenza) il linguaggio tardogotico si manifesta tra Sicilia e Calabria come un feno- meno vitale che si protrae almeno fino ai primi decenni del XVI secolo ed è riscontrabile in mol- teplici fabbriche che la storia ci ha consegnato in resti o frammenti di resti. Il rinascimento si affaccia nel nord est della Sicilia con l’opera di scultori che usano il marmo bianco di Carrara (attivi soprattutto a Messina e Catania) e che sono impegnati nella realizzazione di monumenti, altari, cappelle, portali ecc. Da questo punto di vista Messina segue una parabola analoga a quella di Palermo dove l’architettura tardogotica convive con la scultura rinascimentale. L’influenza del classicismo del marmo, della tradizione tardogotica e il dibattito che si innesca nel duomo di Messina, un cantiere che si andava completando ancora nel corso del primo Cinquecento, sembrano generare nei centri della provincia una serie di sin- golari episodi in cui viene sperimentata la possibilità di contaminazione e ibridazione (portali di Tortorici, Mirto, Mistretta ecc.). -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

Presentazione Di Powerpoint

2nd International Conference of Evidence-Based Health Care Teachers & Developers Sign posting the future in EBHC Utveggio Castle, Palermo (Italy) - September 10-14, 2003 Benvenuti in Sicilia © 1996-2003 - GIMBE The power of Internet Evidence-Based Health Discussion List Subject: conference on teaching ebm/ websites/ sources of materials/ collaboration/ & CATs (or Pearls) From: Martin Dawes ([email protected]) Date: 22 May 2000 - 11:28 BST © 1996-2003 - GIMBE • Some time ago I invited comments about such a meeting. • I received 21 replies all of whom were positive - with some helpful suggestions. • How long was agreed at 2-3 days. • Some interesting ideas: - developing methods to evaluate teaching performance - developing criteria to evaluate effectiveness of workshops • I suggest March 2001 is about practical • I have the e-mails of the people who responded initially and I will approach them to make up an organising committee - anyone else who wants to help Please take one step forward Martin Dawes © 1996-2003 - GIMBE Where ? The question of where was determined by the origin of the sender © 1996-2003 - GIMBE At the time my proposal was… Possibly in Europe, ideally in Italy, it would be fantastic in Sicily! © 1996-2003 - GIMBE What is Evidence-based Medicine? • Paradigm • Reference • Dogma • Neologism • Philosophy • New orthodoxy •… © 1996-2003 - GIMBE Guyatt GH Evidence-based Medicine ACP Journal Club 1991;Mar-Apr:A-16 © 1996-2003 - GIMBE September 2001.Ten years later EBM was the occasion for the irresistible wish -

The Crucifixion C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Italian Thirteenth and Fourteenth Century Paintings Paolo Veneziano Venetian, active 1333 - 1358 The Crucifixion c. 1340/1345 tempera on panel painted surface: 31 x 38 cm (12 3/16 x 14 15/16 in.) overall: 33.85 x 41.1 cm (13 5/16 x 16 3/16 in.) framed: 37.2 x 45.4 x 5.7 cm (14 5/8 x 17 7/8 x 2 1/4 in.) Inscription: upper center: I.N.R.I. (Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews) Samuel H. Kress Collection 1939.1.143 ENTRY The Crucifixion is enacted in front of the crenellated wall of the city of Jerusalem. The cross is flanked above by four fluttering angels, three of whom collect the blood that flows from the wounds in Christ’s hands and side. To the left of the Cross, the Holy Women, a compact group, support the swooning Mary, mother of Jesus. Mary Magdalene kneels at the foot of the Cross, caressing Christ’s feet with her hands. To the right of the Cross stand Saint John the Evangelist, in profile, and a group of soldiers with the centurion in the middle, distinguished by a halo, who recognizes the Son of God in Jesus.[1] The painting’s small size, arched shape, and composition suggest that it originally belonged to a portable altarpiece, of which it formed the central panel’s upper tier [fig. 1].[2] The hypothesis was first advanced by Evelyn Sandberg-Vavalà (originally drafted 1939, published 1969), who based it on stylistic, compositional, and iconographic affinities between a small triptych now in the Galleria Nazionale of Parma [fig.