A History of Western

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observing Protest from a Place

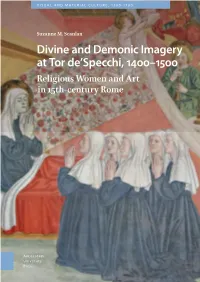

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Nanni Di Banco and Donatello: a Comparison Paolo Vaccarino

New Mexico Quarterly Volume 22 | Issue 4 Article 7 1952 Nanni di Banco and Donatello: A Comparison Paolo Vaccarino Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq Recommended Citation Vaccarino, Paolo. "Nanni di Banco and Donatello: A Comparison." New Mexico Quarterly 22, 4 (1952). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmq/vol22/iss4/7 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Mexico Press at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Quarterly by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r ," ~' Vaccarino: Nanni di Banco and Donatello: A Comparison II l. Paolo VaccaTino NANNI DI BANCO AND I DONATELLO: A COMPARISON 1 <. From the Foreword THE REI S a gap in our knowledge which no scholar has ever tried to fill. It is a gap which owes to the lack ofreal attention paid to the work of Nanni di Banco. To fill it is important not only be came of the fact of his amazing artistry, but because the lack of true familiarity with Nanni and his accomplishments has left a hole where a key should be in our knowledge of Renaissan~e art. The art history of the period has inevitably been somewhat in comprehensible, somewhere lacking in logical development. Without the key figure of Nanni, one is at a loss to explain the development of Donatello on one side and Luca della Robbia on the other; or to fill the gap between Giotto and Masaccio, and trace the history of later painters. -

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

Resurrecting Della Robbia's Resurrection

Article: Resurrecting della Robbia’s Resurrection: Challenges in the Conservation of a Monumental Renaissance Relief Author(s): Sara Levin, Nick Pedemonti, and Lisa Bruno Source: Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twenty-Four, 2017 Pages: 388–412 Editors: Emily Hamilton and Kari Dodson, with Tony Sigel Program Chair ISSN (print version) 2169-379X ISSN (online version) 2169-1290 © 2019 by American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 727 15th Street NW, Suite 500, Washington, DC 20005 (202) 452-9545 www.culturalheritage.org Objects Specialty Group Postprints is published annually by the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC). It is a conference proceedings volume consisting of papers presented in the OSG sessions at AIC Annual Meetings. Under a licensing agreement, individual authors retain copyright to their work and extend publications rights to the American Institute for Conservation. Unless otherwise noted, images are provided courtesy of the author, who has obtained permission to publish them here. This article is published in the Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twenty-Four, 2017. It has been edited for clarity and content. The article was peer-reviewed by content area specialists and was revised based on this anonymous review. Responsibility for the methods and materials described herein, however, rests solely with the author(s), whose article should not be considered an official statement of the OSG or the AIC. OSG2017-Levin.indd 1 12/4/19 6:45 PM RESURRECTING DELLA ROBBIA’S RESURRECTION: CHALLENGES IN THE CONSERVATION OF A MONUMENTAL RENAISSANCE RELIEF SARA LEVIN, NICK PEDEMONTI, AND LISA BRUNO The Resurrection (ca. -

The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2Nd Ed

Abraham Bloemaert (Gorinchem 1566 – 1651 Utrecht) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Abraham Bloemaert” (2017). Revised by Piet Bakker (2019). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 2nd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. New York, 2017–20. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/abraham-bloemaert/ (archived June 2020). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. Abraham Bloemaert was born in Gorinchem on Christmas Eve, 1566. His parents were Cornelis Bloemaert (ca. 1540–93), a Catholic sculptor who had fled nearby Dordrecht, and Aeltgen Willems.[1] In 1567, the family moved to ’s-Hertogenbosch, where Cornelis worked on the restoration of the interior of the St. Janskerk, which had been badly damaged during the Iconoclastic Fury of 1566. Cornelis returned to Gorinchem around 1571, but not for long; in 1576, he was appointed city architect and engineer of Utrecht. Abraham’s mother had died some time earlier, and his father had taken a second wife, Marigen Goortsdr, innkeeper of het Schilt van Bourgongen. Bloemaert probably attended the Latin school in Utrecht. He received his initial art education from his father, drawing copies of the work of the Antwerp master Frans Floris (1519/20–70). According to Karel van Mander, who describes Bloemaert’s work at length in his Schilder-boek, his subsequent training was fairly erratic.[2] His first teacher was Gerrit Splinter, a “cladder,” or dauber, and a drunk. The young Bloemaert lasted barely two weeks with him.[3] His father then sent him to Joos de Beer (active 1575–91), a former pupil of Floris. -

The Triumph of Flora

Myths of Rome 01 repaged 23/9/04 1:53 PM Page 1 1 THE TRIUMPH OF FLORA 1.1 TIEPOLO IN CALIFORNIA Let’s begin in San Francisco, at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor in Lincoln Park. Through the great colonnaded court, past the Corinthian columns of the porch, we enter the gallery and go straight ahead to the huge Rodin group in the central apse that dominates the visitor’s view. Now look left. Along a sight line passing through two minor rooms, a patch of colour glows on the far wall. We walk through the Sichel Glass and the Louis Quinze furniture to investigate. The scene is some grand neo-classical park, where an avenue flanked at the Colour plate 1 entrance by heraldic sphinxes leads to a distant fountain. To the right is a marble balustrade adorned by three statues, conspicuous against the cypresses behind: a muscular young faun or satyr, carrying a lamb on his shoulder; a mature goddess with a heavy figure, who looks across at him; and an upright water-nymph in a belted tunic, carrying two urns from which no water flows. They form the static background to a riotous scene of flesh and drapery, colour and movement. Two Amorini wrestle with a dove in mid-air; four others, airborne at a lower level, are pulling a golden chariot or wheeled throne, decorated on the back with a grinning mask of Pan. On it sits a young woman wearing nothing but her sandals; she has flowers in her hair, and a ribboned garland of flowers across her thighs. -

Illustrations Ij

Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiii Illustrations ij Fig. 1. Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1015, Doors of St. Michael’s, Hildesheim, Germany. Fig. 2. Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1425, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Flo- rence. Fig. 3. Bernardo Rossellino, Facade of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 4. Bernardo Rossellino, Interior of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 5. Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495–98, Refectory of the Monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Fig. 6. Anonymous Pisan artist, Pisa Cross #15, late twelfth century, Museo Civico, Pisa. Fig. 7. Anonymous artist, Cross of San Damiano, late twelfth century, Basilica of Santa Chiara, Assisi. Fig. 8. Giotto di Bondone, Cruci‹xion, ca. 1305, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua. Fig. 9. Masaccio, Trinity Fresco, ca. 1427, Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Fig. 10. Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Altarpiece of St. Francis, 1235, Church of San Francesco, Pescia. Fig. 11. St. Francis Master, St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, early four- teenth century, Upper Church of San Francesco, Assisi. Fig. 12. Anonymous Florentine artist, Detail of the Misericordia Fresco from the Loggia del Bigallo, 1352, Council Chamber, Misericor- dia Palace, Florence. Fig. 13. Florentine artist (Francesco Rosselli?), “Della Catena” View of Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiv ILLUSTRATIONS Florence, 1470s, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Fig. 14. Present-day view of Florence from the Costa San Giorgio. Fig. 15. Nicola Pisano, Nativity Panel, 1260, Baptistery Pulpit, Baptis- tery, Pisa. Fig. -

View / Open Whitford Kelly Anne Ma2011fa.Pdf

PRESENT IN THE PERFORMANCE: STEFANO MADERNO’S SANTA CECILIA AND THE FRAME OF THE JUBILEE OF 1600 by KELLY ANNE WHITFORD A THESIS Presented to the Department of Art History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2011 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kelly Anne Whitford Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of Art History by: Dr. James Harper Chairperson Dr. Nicola Camerlenghi Member Dr. Jessica Maier Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research & Innovation/Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2011 ii © 2011 Kelly Anne Whitford iii THESIS ABSTRACT Kelly Anne Whitford Master of Arts Department of Art History December 2011 Title: Present in the Performance: Stefano Maderno’s Santa Cecilia and the Frame of the Jubilee of 1600 In 1599, in commemoration of the remarkable discovery of the incorrupt remains of the early Christian martyr St. Cecilia, Cardinal Paolo Emilio Sfondrato commissioned Stefano Maderno to create a memorial sculpture which dramatically departed from earlier and contemporary monuments. While previous scholars have considered the influence of the historical setting on the conception of Maderno’s Santa Cecilia, none have studied how this historical moment affected the beholder of the work. In 1600, the Church’s Holy Year of Jubilee drew hundreds of thousands of pilgrims to Rome to take part in Church rites and rituals. -

A.P. Art History Simplified Timeline Through 1900 Note: These Are Approximate Dates

Marsha K. Russell 1 St. Andrew's Episcopal School, Austin, TX A.P. Art History Simplified Timeline through 1900 Note: These are approximate dates. Remember periods and styles overlap. Prehistory Paleolithic: up to about 10,000 BCE • Venus/Goddess of Willendorf • Lascaux Cave Paintings • Altamira Cave Paintings Neolithic in England: about 2,000 BCE • Stonehenge Mesopotamia/Near East (ignore time lapses) Sumerian: ~3500 - 2300 BCE • Standard of Ur • Ram offering stand • Bull-headed lyre • Bull holding a Vase • Ziggurats Akkadian: ~2300 - 2200 BCE • Victory Stele of Naram-Sin Neo Sumerian: ~2200 - 2000 BCE • Gudea statues Babylonian: ~1900 - 1600 BCE • Stele of Hammurabi Assyrian: ~900 - 600 BCE • Lamassu (Winged Human-Headed Bull) • Lion Hunt Bas Reliefs Egypt Predynastic: 3500 - 3000 BCE • Palette of Narmer Old Kingdom: ~3000 - 2200 BCE • Khafre • Menkaure and Khamerernebty • Seated Scribe • Ti Watching a Hippo Hunt • Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret • Pyramid of King Djoser by Imhotep Middle Kingdom: ~2100 - 1600 BCE • Rock-cut tomb New Kingdom: ~1500 - 40 BCE (includes the Amarna Period 1355 – 1325 BCE) • Funerary Temple of Hatshepsut • Temple of Ramses II • Temple of Amen-Re at Karnak • Akhenaton • Akhenaton and His Family Marsha K. Russell 2 St. Andrew's Episcopal School, Austin, TX Aegean & Greece Minoan: ~2000 - 1500 BCE • Snake Goddess • Palace at Knossos • Dolphin Fresco • Toreador Fresco • Octopus Vase Mycenean: ~1500 - 1100 BCE • "Treasury of Atreus" with its corbelled vault • Repoussé masks • Lion Gate at Mycenae • Inlaid dagger -

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: VENETIAN RENAISSANCE and MANNERISM (Titian and Pontormo) VENETIAN RENAISSANCE

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: VENETIAN RENAISSANCE and MANNERISM (Titian and Pontormo) VENETIAN RENAISSANCE Online Links: Giovanni Bellini - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Feast of the Gods – Smarthistory The Tempest - Smarthistory Titian - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bacchus and Ariadne – Smarthistory Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne- National Gallery Podcast Venus of Urbino - Smarthistory Giorgione - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Venus of Urbino - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia MANNERISM Online Links: Introduction to Mannerism - Smarthistory Correggio's Assumption of the Virgin - Smarthistory (no video) Parmigianino's Madonna of the Long Neck – Smarthistory Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus Beheading Medusa Benvenuto Cellini - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Pontormo's Entombment - Smarthistory Giovanni Bellini and Titian. The Feast of the Gods, 1529, oil on canvas Above: Map of 16th century Venice Left: Giovanni Bellini. Self-Portrait The High Renaissance in Venice coincided with the decline of the empire and the threat that the city would lose the independent status it had enjoyed for eight hundred years. Formidable foreign powers such as the French and Spanish kings, the pope, the Holy Roman emperor, and the rulers of Milan united against Venice and formed the League of Cambrai in 1509. They took most of the Venetian territory, including the important city of Verona, but not Venice itself. By 1529, peace was restored along with most of the territory, and Venice propagated the myth of its uniqueness in having survived so great a threat. In this illustration of a scene from Ovid’s, Fasti the gods, Jupiter, Neptune, and Apollo among them, revel in a wooded pastoral setting, eating and drinking, attended by nymphs and satyrs. -

The Scientific Narrative of Leonardoâ•Žs Last Supper

Best Integrated Writing Volume 5 Article 4 2018 The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper Amanda Grieve Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biw Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grieve, A. (2018). The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper, Best Integrated Writing, 5. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Best Integrated Writing by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact library- [email protected]. AMANDA GRIEVE ART 3130 The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper AMANDA GRIEVE ART 3130: Leonardo da Vinci, Fall 2017 Nominated by: Dr. Caroline Hillard Amanda Grieve is a senior at Wright State University and is pursuing a BFA with a focus on Studio Painting. She received her Associates degree in Visual Communications from Sinclair Community College in 2007. Amanda notes: I knew Leonardo was an incredible artist, but what became obvious after researching and learning more about the man himself, is that he was a great thinker and intellectual. I believe those aspects of his personality greatly influenced his art and, in large part, made his work revolutionary for his time. Dr. Hillard notes: This paper presents a clear and original thesis about Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper that incorporates important scholarly research and Leonardo’s own writings. The literature on Leonardo is extensive, yet the author has identified key studies and distilled their essential contributions with ease.