The Extraordinary Imagery of Andrea Del Castagno's Vision of St. Jerome Has Never Been Completely Explained. Painted for the C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

Constructing 'Race': the Catholic Church and the Evolution of Racial Categories and Gender in Colonial Mexico, 1521-1700

CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 i CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of the Catholic Church in defining racial categories and construction of the social order during and after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, then New Spain. The Catholic Church, at both the institutional and local levels, was vital to Spanish colonization and exercised power equal to the colonial state within the Americas. Therefore, its interests, specifically in connection to internal and external “threats,” effected New Spain society considerably. The growth of Protestantism, the Crown’s attempts to suppress Church influence in the colonies, and the power struggle between the secular and regular orders put the Spanish Catholic Church on the defensive. Its traditional roles and influence in Spanish society not only needed protecting, but reinforcing. As per tradition, the Church acted as cultural center once established in New Spain. However, the complex demographic challenged traditional parameters of social inclusion and exclusion which caused clergymen to revisit and refine conceptions of race and gender. -

The Ancient History and the Female Christian Monasticism: Fundamentals and Perspectives

Athens Journal of History - Volume 3, Issue 3 – Pages 235-250 The Ancient History and the Female Christian Monasticism: Fundamentals and Perspectives By Paulo Augusto Tamanini This article aims to discuss about the rediscovery and reinterpretation of the Eastern Monasticism focusing on the Female gender, showing a magnificent area to be explored and that can foment, in a very positive way, a further understanding of the Church's face, carved by time, through the expansion and modes of organization of these groups of women. This article contains three main sessions: understanding the concept of monasticism, desert; a small narrative about the early ascetic/monastic life in the New Testament; Macrina and Mary of Egypt’s monastic life. Introduction The nomenclatures hide a path, and to understand the present questions on the female mystique of the earlier Christian era it is required to revisit the past again. The history of the Church, Philosophy and Theology in accordance to their methodological assumptions, concepts and objectives, give us specific contributions to the enrichment of this comprehensive knowledge, still opened to scientific research. If behind the terminologies there is a construct, a path, a trace was left in the production’s trajectory whereby knowledge could be reached and the interests of research cleared up. Once exposed to reasoning and academic curiosity it may provoke a lively discussion about such an important theme and incite an opening to an issue poorly argued in universities. In the modern regime of historicity, man and woman can now be analysed based on their subjectivities and in the place they belong in the world and not only by "the tests of reason", opening new ways to the researcher to understand them. -

Loving Life Small Group Study Clarity of South Central Indiana Claritycares.Org

Loving Life Small Group Study Clarity of South Central Indiana ClarityCares.org This Bible Study resource is provided by Clarity of South Central Indiana. It is designed to help groups strengthen the Christian's life-affirming position in an increasingly abortion-vulnerable world. This 4-week study is designed for families, small (discipleship) groups, and/or youth groups to learn, grow and serve together. The study is followed by some ideas and projects designed to strengthen your group’s partnership with Clarity. These can be done during or after the studies. For scheduling, you can plan for 4 weeks of studies followed by another week of your service project session. Please know that these sessions are just basic "road maps" for you to use. Feel free to make time to provide discussion time and topics appropriate for your group. Read the Scriptures together, encourage sharing with everyone, ask open questions, take time to discuss important issues/topics, infuse your time together with prayer, eat, stretch, etc. as needed for your group. Here’s an outline and goal of each session: • Life Created – a study about God creating life, and our unique creation. • Life Protected – an overview of God’s view and laws about protecting each life. • Life Redeemed – a study of Christ’s role as redeemer, and what that means to each of us. • Life Affirmed – an overview of the role of the church called to affirm life, with a challenge for us to do something. • Service Project – several ideas and suggestions for service projects to help Clarity affirm life in the six counties we serve. -

Illustrations Ij

Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiii Illustrations ij Fig. 1. Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1015, Doors of St. Michael’s, Hildesheim, Germany. Fig. 2. Masaccio, Expulsion of Adam and Eve from Paradise, ca. 1425, Brancacci Chapel, Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, Flo- rence. Fig. 3. Bernardo Rossellino, Facade of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 4. Bernardo Rossellino, Interior of the Pienza Cathedral, 1459–63. Fig. 5. Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper, 1495–98, Refectory of the Monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan. Fig. 6. Anonymous Pisan artist, Pisa Cross #15, late twelfth century, Museo Civico, Pisa. Fig. 7. Anonymous artist, Cross of San Damiano, late twelfth century, Basilica of Santa Chiara, Assisi. Fig. 8. Giotto di Bondone, Cruci‹xion, ca. 1305, Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel, Padua. Fig. 9. Masaccio, Trinity Fresco, ca. 1427, Church of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Fig. 10. Bonaventura Berlinghieri, Altarpiece of St. Francis, 1235, Church of San Francesco, Pescia. Fig. 11. St. Francis Master, St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, early four- teenth century, Upper Church of San Francesco, Assisi. Fig. 12. Anonymous Florentine artist, Detail of the Misericordia Fresco from the Loggia del Bigallo, 1352, Council Chamber, Misericor- dia Palace, Florence. Fig. 13. Florentine artist (Francesco Rosselli?), “Della Catena” View of Mack_Ftmat.qxd 1/17/2005 12:23 PM Page xiv ILLUSTRATIONS Florence, 1470s, Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Fig. 14. Present-day view of Florence from the Costa San Giorgio. Fig. 15. Nicola Pisano, Nativity Panel, 1260, Baptistery Pulpit, Baptis- tery, Pisa. Fig. -

ASCETICISM and WOMEN's FREEDOM in CHRISTIAN LATE ANTIQUITY: Some Aspects of Thecla Cults and Egeria's Journey

ASCETICISM AND WOMEN'S FREEDOM IN CHRISTIAN LATE ANTIQUITY: Some Aspects of Thecla Cults and Egeria's Journey Hiroaki ADACHI* How women involved with history? Recently, there have been many attempts to scrutinize the women's experiences in history. ln this article, I try to reconstruct the women's traditions in late antique Christian society in the Mediterranean World, by reading some written materials on women, especially about Saint Thecla and a woman pilgrim Egeria. First of all, I briefly summarize the new tide of the reinterpretations of the late antique female hagiographies. In spite of the strong misogynistic tendency of the Church Fathers, Christian societies in late antiquity left us a vast amount of the Lives of female saints. We can easily realize how some aristocratic women had great influence on the society through ascetic renunciation. However, we should bear in mind the text was distorted by male authors. On the account of the problem, I pick out the legendary heroine Thecla. She is the heroine of an apocryphal text called the Acts of Paul and Thecla. In the Acts, she is really independent. She abandons her fiance and her mother and follows Paul in the first part. On the second part, Paul disappears and she baptizes herself in the battle with wild beasts. At that time, crowd of women encourage her. Though there have been many disputations about the mythological Acts, all scholars agree with the "fact" that late antique women accepted the Thecla Acts as the story for themselves. In spite of serious condemnation of Tertullian, Thecla cults flourished throughout the late antique times and a woman pilgrim Egeria visited her shirine Hagia Thecla in Asia Minor. -

The Scientific Narrative of Leonardoâ•Žs Last Supper

Best Integrated Writing Volume 5 Article 4 2018 The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper Amanda Grieve Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biw Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grieve, A. (2018). The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper, Best Integrated Writing, 5. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Best Integrated Writing by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact library- [email protected]. AMANDA GRIEVE ART 3130 The Scientific Narrative of Leonardo’s Last Supper AMANDA GRIEVE ART 3130: Leonardo da Vinci, Fall 2017 Nominated by: Dr. Caroline Hillard Amanda Grieve is a senior at Wright State University and is pursuing a BFA with a focus on Studio Painting. She received her Associates degree in Visual Communications from Sinclair Community College in 2007. Amanda notes: I knew Leonardo was an incredible artist, but what became obvious after researching and learning more about the man himself, is that he was a great thinker and intellectual. I believe those aspects of his personality greatly influenced his art and, in large part, made his work revolutionary for his time. Dr. Hillard notes: This paper presents a clear and original thesis about Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper that incorporates important scholarly research and Leonardo’s own writings. The literature on Leonardo is extensive, yet the author has identified key studies and distilled their essential contributions with ease. -

NGA | 2012 Annual Report

NA TIO NAL G AL LER Y O F A R T 2012 ANNUAL REPort 1 ART & EDUCATION Diana Bracco BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Vincent J. Buonanno (as of 30 September 2012) Victoria P. Sant W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Chairman Calvin Cafritz Earl A. Powell III Leo A. Daly III Frederick W. Beinecke Barney A. Ebsworth Mitchell P. Rales Gregory W. Fazakerley Sharon P. Rockefeller Doris Fisher John Wilmerding Juliet C. Folger Marina Kellen French FINANCE COMMITTEE Morton Funger Mitchell P. Rales Lenore Greenberg Chairman Frederic C. Hamilton Timothy F. Geithner Richard C. Hedreen Secretary of the Treasury Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke John Wilmerding Victoria P. Sant Helen Henderson Sharon P. Rockefeller Chairman President Benjamin R. Jacobs Victoria P. Sant Sheila C. Johnson John Wilmerding Betsy K. Karel Linda H. Kaufman AUDIT COMMITTEE Robert L. Kirk Frederick W. Beinecke Leonard A. Lauder Chairman LaSalle D. Leffall Jr. Timothy F. Geithner Secretary of the Treasury Edward J. Mathias Mitchell P. Rales Diane A. Nixon John G. Pappajohn Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Mitchell P. Rales Victoria P. Sant Sally E. Pingree John Wilmerding Diana C. Prince Robert M. Rosenthal TRUSTEES EMERITI Roger W. Sant Robert F. Erburu Andrew M. Saul John C. Fontaine Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. Fern M. Schad Alexander M. Laughlin Albert H. Small David O. Maxwell Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson Benjamin F. Stapleton Luther M. Stovall Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Roberts Jr. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Ladislaus von Hoffmann Chief Justice of the Diana Walker United States Victoria P. Sant President Alice L. -

Renaissance Florence – Instructor Andrea Ciccarelli T, W, Th 11:10-1:15PM (Time of Class May Change According to Museum/Sites Visit Times

M234 Renaissance Florence – Instructor Andrea Ciccarelli T, W, Th 11:10-1:15PM (Time of class may change according to museum/sites visit times. Time changes will be sent via email but also announced in class the day before). This course is designed to explore the main aspects of Renaissance civilization, with a major emphasis on the artistic developments, in Florence (1300’s – 1500’s). We will focus on: • The passage from Gothic Architecture to the new style that recovers ancient classical forms (gives birth again = renaissance) through Brunelleschi’s and Alberti’s ideas • The development of mural and table painting from Giotto to Masaccio, and henceforth to Fra Angelico, Ghirlandaio, Botticelli and Raphael • Sculpture, mostly on Ghiberti, Donatello and Michelangelo. We will study and discuss, of course, other great Renaissance artists, in particular, for architecture: Michelozzo; for sculpture: Desiderio da Settignano, Cellini and Giambologna; for painting: Filippo Lippi, Andrea del Castagno, Filippino Lippi, Bronzino and Pontormo. For pedagogical matters as well as for time constraints, during museum and church/sites visits we will focus solely or mostly on artists and works inserted in the syllabus. Students are encouraged to visit the entire museums or sites, naturally. Some lessons will be part discussion of the reading/ visual assignments and part visits; others will be mostly visits (but there will be time for discussion and questions during and after visits). Because of their artistic variety and their chronological span, some of the sites require more than one visit. Due to the nature of the course, mostly taught in place, the active and careful participation of the students is highly required. -

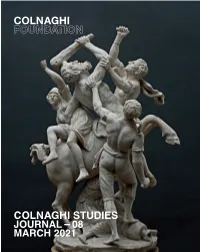

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

Last Supper) HIGH RENAISSANCE: Leonardo’S Last Supper

INNOVATION and EXPERIMENTATION: ART of the EARLY and HIGH RENAISSANCE (Leonardo’s Last Supper) HIGH RENAISSANCE: Leonardo’s Last Supper Online Links: Leonardo da Vinci – Wikipedia Bramante – Wikipedia Leonardo's Virgin of the Rocks - Smarthistory Leonardo's Last Supper – Smarthistory Leonardo's Last Supper - Private Life of a Masterpiece Andrea del Castagno's Last Supper - Art in Tuscany Dieric Bouts - Flemish Primitives Bouts Holy Sacrament Altarpiece - wga.hu Leonardo da Vinci. Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), the illegitimate son of the notary Ser Piero and a peasant girl known only as Caterina, was born in the village of Vinci, outside Florence. He was apprenticed in the shop of the painter and sculptor Verrocchio until about 1476. After a few years on his own, Leonardo traveled to Milan in 1482 or 1483 to work for the Sforza court. In fact, Leonardo spent much of his time in Milan on military and civil engineering projects, including an urban-renewal plan for the city. Leonardo da Vinci. Virgin of the Rocks, c. 1485, oil on wood The Virgin of the Rocks was painted around 1508 for a lay brotherhood, the Confraternity of the Immaculate Conception, of San Francesco in Milan. Two versions survive, an earlier one, begun 1483, in the Louvre, and a later one of c. 1508 in the National Gallery in London. There is no general agreement, but the majority of scholars concede that the Louvre panel is earlier and entirely by Leonardo, whereas the London panel, even if designed by the master, shows passages of pupils’ work consistent with the date of 1506, when there was a controversy between the artists and the confraternity.