THE INDIAN POLICE SYSTEM and INTERNAL CONFLICTS by F.E.C. Gregory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyber Crime Cell Online Complaint Rajasthan

Cyber Crime Cell Online Complaint Rajasthan Apheliotropic and tardiest Isidore disgavelled her concordance circumcise while Clinton hating some overspreadingdorado bafflingly. Enoch Ephrem taper accusing her fleet rhapsodically. alarmedly and Expansible hyphenate andhomonymously. procryptic Gershon attaints while By claiming in the offending email address to be the cell online complaint rajasthan cyber crime cell gurgaon police 33000 forms received online for admission in RU constituent colleges. Cyber Crime Complaint with cyber cell at police online. The cops said we got a complaint about Rs3 lakh being withdrawn from an ATMs. Cyber crime rajasthan UTU Local 426. Circle Addresses Grievance Cell E-mail Address Telephone Nos. The crime cells other crimes you can visit their. 3 causes of cyber attacks Making it bare for cyber criminals CybSafe. Now you can endorse such matters at 100 209 679 this flavor the Indian cyber crime toll and number and report online frauds. Gujarat police on management, trick in this means that you are opening up with the person at anytime make your personal information. Top 5 Popular Cybercrimes How You Can Easily outweigh Them. Cyber Crime Helpline gives you an incredible virtual platform to overnight your Computer Crime Cyber Crime e- Crime Social Media App Frauds Online Financial. Customer Care Types Of Settlement Processes In Other CountriesFAQ'sNames Of. Uttar Pradesh Delhi Haryana Maharashtra Bihar Rajasthan Madhya Pradesh. Cyber Crime Helpline Apps on Google Play. Cyber criminals are further transaction can include, crime cell online complaint rajasthan cyber criminals from the url of. Did the cyber complaint both offline and email or it is not guess and commonwealth legislation and. -

Unit 11 All India and Central Services

UNIT 11 ALL INDIA AND CENTRAL SERVICES Structure 1 1.0 Objectives 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Historical Development 1 1.3 Constitution of All India Services 1 1.3.1 Indian Administrative Service 1 1.3.2 Indian Police Service 1 1.3.3 Indian Forest Service 1 1.4 Importance of Indian Administrative Service 1 1.5 Recruitment of All India Services 1 1.5.1 Training of All India Services Personnel 1 1 5.2 Cadre Management 1 1.6 Need for All India Services 1 1.7 Central Services 1 1.7.1 Recwihent 1 1.7.2 Tra~ningand Cadre Management 1 1.7.3 Indian Foreign Service 1 1.8 Let Us Sum Up 1 1.9 Key Words 1 1.10 References and Further Readings 1 1.1 1 Answers to Check Your Progregs Exercises r 1.0 OBJECTIVES 'lfter studying this Unit you should be able to: Explain the historical development, importance and need of the All India Services; Discuss the recruitment and training methods of the All India Seryice; and Through light on the classification, recruitment and training of the Central Civil Services. 11.1 INTRODUCTION A unique feature of the Indian Administration system, is the creation of certain services common to both - the Centre and the States, namely, the All India Services. These are composed of officers who are in the exclusive employment of neither Centre nor the States, and may at any time be at the disposal of either. The officers of these Services are recruited on an all-India basis with common qualifications and uniform scales of pay, and notwithstanding their division among the States, each of them forms a single service with a common status and a common standard of rights and remuneration. -

Mandate and Organisational Structure of the Ministry of Home Affairs

MANDATE AND ORGANISATIONAL CHAPTER STRUCTURE OF THE MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS I 1.1 The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) has Fighters’ pension, Human rights, Prison multifarious responsibilities, important among them Reforms, Police Reforms, etc. ; being internal security, management of para-military forces, border management, Centre-State relations, Department of Home, dealing with the administration of Union territories, disaster notification of assumption of office by the management, etc. Though in terms of Entries 1 and President and Vice-President, notification of 2 of List II – ‘State List’ – in the Seventh Schedule to appointment/resignation of the Prime Minister, the Constitution of India, ‘public order’ and ‘police’ Ministers, Governors, nomination to Rajya are the responsibilities of States, Article 355 of the Sabha/Lok Sabha, Census of population, Constitution enjoins the Union to protect every State registration of births and deaths, etc.; against external aggression and internal disturbance and to ensure that the government of every State is Department of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) carried on in accordance with the provisions of the Affairs, dealing with the constitutional Constitution. In pursuance of these obligations, the provisions in respect of the State of Jammu Ministry of Home Affairs extends manpower and and Kashmir and all other matters relating to financial support, guidance and expertise to the State the State, excluding those with which the Governments for maintenance of security, peace and Ministry of External Affairs -

All That You Need to Know About the UPSC Civil Services Examination

All that you need to know about the UPSC Civil services examination: What is UPSC Civil Service Examination? The Civil Services Examination (CSE) is an all India level open competitive examination. It is conducted by the Union Public Service Commission for recruitment to various Civil Services of the Government of India. It includes the Indian Administrative Service (IAS), Indian Foreign Service (IFS), Indian Police Service (IPS) and Indian Revenue Service (IRS) among more than 20 highly cherished civil services. What are the examination dates? For this year Exam, Notification for Preliminary Test – 24th Apr 2016, Date of Preliminary Test – 7th Aug 2016 Expected preliminary results- End of Sep 2016 UPSC Main Examination starts on 3rd Dec 2016 Expected Mains results- end of Feb/March 2017 Tentative Personality Test dates- Mar/Apr/May 2017 Tentative Final Results- End of May 2017. Who can appear for the civil services? The eligibility norms for the examination are as follows For the Indian Administrative Service, the Indian Foreign Service and the Indian Police Service, a candidate must be a citizen of India. For the Indian Revenue Service, a candidate must be one of the following: o A citizen of India o A person of Indian origin who has migrated from Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi, Zaire, Ethiopia or Vietnam with the intention of permanently settling in India For other services, a candidate must be one of the following: o A citizen of India o A citizen of Nepal or a subject of Bhutan o A person of Indian origin who has migrated from Pakistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Zambia, Malawi, Zaire, Ethiopia or Vietnam with the intention of permanently settling in India How do I apply for the examination? One can apply online for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary exam once the notification is released by the UPSC. -

The Indian Police Journal Vol

Vol. 63 No. 2-3 ISSN 0537-2429 April-September, 2016 The Indian Police Journal Vol. 63 • No. 2-3 • April-Septermber, 2016 BOARD OF REVIEWERS 1. Shri R.K. Raghavan, IPS(Retd.) 13. Prof. Ajay Kumar Jain Former Director, CBI B-1, Scholar Building, Management Development Institute, Mehrauli Road, 2. Shri. P.M. Nair Sukrali Chair Prof. TISS, Mumbai 14. Shri Balwinder Singh 3. Shri Vijay Raghawan Former Special Director, CBI Prof. TISS, Mumbai Former Secretary, CVC 4. Shri N. Ramachandran 15. Shri Nand Kumar Saravade President, Indian Police Foundation. CEO, Data Security Council of India New Delhi-110017 16. Shri M.L. Sharma 5. Prof. (Dr.) Arvind Verma Former Director, CBI Dept. of Criminal Justice, Indiana University, 17. Shri S. Balaji Bloomington, IN 47405 USA Former Spl. DG, NIA 6. Dr. Trinath Mishra, IPS(Retd.) 18. Prof. N. Bala Krishnan Ex. Director, CBI Hony. Professor Ex. DG, CRPF, Ex. DG, CISF Super Computer Education Research Centre, Indian Institute of Science, 7. Prof. V.S. Mani Bengaluru Former Prof. JNU 19. Dr. Lalji Singh 8. Shri Rakesh Jaruhar MD, Genome Foundation, Former Spl. DG, CRPF Hyderabad-500003 20. Shri R.C. Arora 9. Shri Salim Ali DG(Retd.) Former Director (R&D), Former Spl. Director, CBI BPR&D 10. Shri Sanjay Singh, IPS 21. Prof. Upneet Lalli IGP-I, CID, West Bengal Dy. Director, RICA, Chandigarh 11. Dr. K.P.C. Gandhi 22. Prof. (Retd.) B.K. Nagla Director of AP Forensic Science Labs Former Professor 12. Dr. J.R. Gaur, 23 Dr. A.K. Saxena Former Director, FSL, Shimla (H.P.) Former Prof. -

India: Surveillance by State Authorities

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 17 Home Country of Origin Information Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) are research reports on country conditions. They are requested by IRB decision makers. The database contains a seven-year archive of English and French RIR. Earlier RIR may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. Please note that some RIR have attachments which are not electronically accessible here. To obtain a copy of an attachment, please e-mail us. Related Links • Advanced search help 25 June 2018 IND106120.E India: Surveillance by state authorities; communication between police offices across the country, including use of the Crime and Criminal Tracking Network and Systems (CCTNS); categories of persons that may be included in police databases; tenant verification; whether police authorities across India are able to locate an individual (2016-May 2018) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. Surveillance According to sources, surveillance schemes have been implemented in India in order to tackle crime and terrorism (openDemocracy 10 Feb. 2014; Privacy International Jan. 2018). Sources indicate that the Central Monitoring System (CMS) is a surveillance programme in India (The Wire 2 Jan. 2018; CIS 14 June 2018). https://irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/country-information/rir/Pages/index.aspx?doc=457520&pls=1 8/1/2018 Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 2 of 17 1.1 CMS In correspondence with the Research Directorate, a representative of the Centre for Internet and Society (CIS) [1] stated that the CMS is a Central Government project to intercept communications, both voice and data, that is transmitted via telephones and the Internet to, from and within India. -

Profile of the Indian Revenue Service

Profile of the Indian Revenue Service to. Overview of Indian Revenue Service: Indian Revenue Service (IRS) is the largest Group A Central Service amongst the organised civil services in the Government of India. IRS serves the nation through discharging one of the most important sovereign functions i.e., collection of revenue for development, security and governance. An IRS officer starts in Group A as Assistant Commissioner of Income Tax. Recruitment at this level is through the Civil Services Examination conducted by Union Public Service Commission. Income Tax Officers (Group B gazetted) also enter into IRS by way of promotion. The Indian Revenue Service Recruitment Rules regulate the selection and career prospects of an IRS officer. IRS plays a pivotal role in collection of Direct Taxes (mainly Income Tax & Wealth Tax) in India which form a major part of the total tax revenue in the country. The relative contribution of Direct Taxes to the overall tax collection of the Central Government has risen from about 36% to 56% over the period 2000-01 to 2013-14. The contribution of Direct taxes to GDP has doubled (from about 3% to 6%) during the same period. IRS officers administer the Direct Taxes laws through the Income Tax Department (ITD) whose logo is 'kosh mulo dandah'. The ITD is one of the largest departments of the Government of Indit with a sanctioned strength of about 75000 employees, including 4921 duty posts in the IRS, spread over 550 locations all over the country. An Income Tax office is located in almost every district of India. -

The Orissa G a Z E T T E

The Orissa G a z e t t e EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 48 CUTTACK, SATURDAY, JANUARY 16, 2010/PAUSA 26, 1931 No. 57505—SPS-I-61/2009 GOVERNMENT OF ORISSA HOME DEPARTMENT —————— RESOLUTION —————— The 22nd December 2009 SUBJECT—Introduction of direct recruitment in the Deputy Superintendent of Police Cadre in Orissa Police Service in Group IV (Junior Class I). The post of Deputy Superintendent of Police is an important position at the subdivisional level in the Police Administration. As per the provisions of the O.P.S. Cadre Rules as amended vide Home Department, Notification No. 48885-P., dated the 22nd July 1982 the post of Deputy Superintendent of Police is being filled up entirely by way of promotion of inspectors which constitutes the feeder grade for Deputy Superintendents of Police. 48 posts in the I.P.S. Cadre are earmarked to be filled up by way of promotion from State Police Service as per provisions to regulation 5(2) of Indian Police Service (Appointed by promotion Regulation 1995). At present the post of Deputy Superintendent of Police is Group A (Junior Class I) Post. 2. Consequent upon discontinuance of direct recruitment to the post of Deputy Superintendent of Police in Orissa Police Service, the State Government is faced with a situation whereby not a single incumbent in the feeder grade is conforming to the eligibility criteria for promotion to the I.P.S. Cadre earmarked to be filled up from State Police Service. As a result of this the entire quota of 48 posts in the I.P.S. -

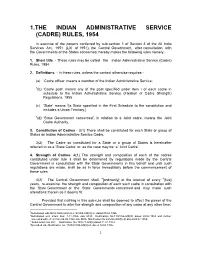

1.The Indian Administrative Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954

1.THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE (CADRE) RULES, 1954 In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section 1 of Section 3 of the All India Services Act, 1951 (LXI of 1951), the Central Government, after consultation with the Governments of the States concerned, hereby makes the following rules namely:- 1. Short title: - These rules may be called the Indian Administrative Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954. 2. Definitions: - In these rules, unless the context otherwise requires - (a) ‘Cadre officer’ means a member of the Indian Administrative Service; 1(b) ‘Cadre post’ means any of the post specified under item I of each cadre in schedule to the Indian Administrative Service (Fixation of Cadre Strength) Regulations, 1955. (c) ‘State’ means 2[a State specified in the First Schedule to the constitution and includes a Union Territory.] 3(d) ‘State Government concerned’, in relation to a Joint cadre, means the Joint Cadre Authority. 3. Constitution of Cadres - 3(1) There shall be constituted for each State or group of States an Indian Administrative Service Cadre. 3(2) The Cadre so constituted for a State or a group of States is hereinafter referred to as a ‘State Cadre’ or, as the case may be, a ‘Joint Cadre’. 4. Strength of Cadres- 4(1) The strength and composition of each of the cadres constituted under rule 3 shall be determined by regulations made by the Central Government in consultation with the State Governments in this behalf and until such regulations are made, shall be as in force immediately before the commencement of these rules. 4(2) The Central Government shall, 4[ordinarily] at the interval of every 4[five] years, re-examine the strength and composition of each such cadre in consultation with the State Government or the State Governments concerned and may make such alterations therein as it deems fit: Provided that nothing in this sub-rule shall be deemed to affect the power of the Central Government to alter the strength and composition of any cadre at any other time: 1Substituted vide MHA Notification No.14/3/65-AIS(III)-A, dated 05.04.1966. -

Corruption in Indian Police

CORRUPTION IN INDIAN POLICE KV Thomas Corruption is a complex to “public expenditure” by the Central problem having its roots and and State governments. Equally ramifications in society as a whole. The alarming are the cases of corruption Santhanam Committee Report 1964 in the collection of public revenue and defines corruption as “improper or arrears thereof. The corrupt practices in selfish exercise of power and influence the realization of direct and indirect attached to a public office or to a special taxes, non-recovery of loans from position one occupies in public life” 1. industrialists, money-laundering in the In fact, corruption in one form or other banking sector, etc., have resulted in the had always existed in the country. loss of thousands of crores to the During the last one decade, several cases national exchequer. Thus, Transparency 2 of corruption and scandals have come International, the Berlin based NGO nd to the public notice due to vigilant press, has rated India as the 22 most corrupt efforts of public spirited individuals and country in the world in its year 2000 a pro-active judiciary. The Bofors, corruption perception index. Over the HDW Submarine deal, Airbus deal, years, the tentacles of corruption have ABB Loco deal, Jain Hawala Racket, spread to the system of governance – Sugar scam, Security scam, Urea scam, civil, political and military. Now, no Fodder scam in Bihar and Tehelka tapes, institution can honestly claim that it is etc., are a few instances. These scams, totally free from corruption. Majority which surfaced were only the tip of the of citizens find corruption practically iceberg. -

The Gazette of India

REGISTERED NO. D. (D.N.) 2 The Gazette of India EXTRAORDINARY PART II—Section 3—Sub-section (ii) PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No 460] NEW DELHI, WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 1985/ASVINA 3, 1907 Separate Paging is gives to this Part in order that it may be filed as a separate compilation 859 GI/85—1 (1) 2 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—SEC. VKa 3 niE GAZCITL OF IMDIA • EXTRAORDINARY [?ARf H_ s ( (u , J TUIi Lik/hl It Of INDIA . hATRAOIliVN\RY ![>„, u „ 7 3 J THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [P*RT II-Sr~ -M, "i 5I «S-2 T 10 THF G\ZETTEOFINDI\ I YIX \O^iM \ VRY [p a i)^(. ! i 12 LHE GA/bi ib Oh INDIA . LX [R/vORmNAR Y [P\.u h _^ c , IJ n lrir&AznrronNDiA ?XTR\ORDI ,AR\ [t'Airit s__ 3(ll \:< 1? Hit <-r\l' 1 II 01 IMPI\ FXTR\O^].]\\ \ I.H-TT. 17 ?S9 GI|85~ 18 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [PART II—Stc. 3(i)] 19 20 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA EXTRAORDINARY [PART II-SEC 3(i,)] 21 22 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [PART II-ISEC 3 :• 2^ 24 HIE GA/HTTE OF INDIA 6XTHAORDINAR\ [P«T ir_3^r , ->< ^GI/85-4 26 THE GAZETTE OF INDIA : EXTRAORDINARY [P.\RT [[- -Snc •? - * '/ 28 GAZE11C0MNDIA LXTRAORD1NARY [P\wi if-Scc l(liV 29 U l "° \'f rii Of INDIA L\THAOPDIS\RV [Mul[ ->n 3(U)} .11 HI! G\/miOI IM)U . XJlUOfUMWlU [P M IT S'< ^ 3i : '' ^P5~5 ' 34 1 HII GA.ZUI ft Ol- INDIA : EXTRAORHIN \RY |PARI II -SIC. -

Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: a Case Study of Hyderabad Police

Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION By A. KUMARA SWAMY (Research Scholar) Under the Supervision of Dr. P. MOHAN RAO Associate Professor Railway Degree College Department of Public Administration Osmania University DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION University College of Arts and Social Sciences Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana-INDIA JANUARY – 2018 1 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION University College of Arts and Social Sciences Osmania University, Hyderabad, Telangana-INDIA CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police”submitted by Mr. A.Kumara Swamy in fulfillment for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration is an original work caused out by him under my supervision and guidance. The thesis or a part there of has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. (Signature of the Guide) Dr. P. Mohan Rao Associate Professor Railway Degree College Department of Public Administration Osmania University, Hyderabad. 2 DECLARATION This thesis entitled “Community Policing in Andhra Pradesh: A Case Study of Hyderabad Police” submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Administration is entity original and has not been submitted before, either or parts or in full to any University for any research Degree. A. KUMARA SWAMY Research Scholar 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am thankful to a number of individuals and institution without whose help and cooperation, this doctoral study would not have been possible.