UC Berkeley Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff F.D.P

Plenarprotokoll 13/52 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 52. Sitzung Bonn, Donnerstag, den 7. September 1995 Inhalt: Zur Geschäftsordnung Dr. Uwe Jens SPD 4367 B Dr. Peter Struck SPD 4394B, 4399A Dr. Otto Graf Lambsdorff F.D.P. 4368B Joachim Hörster CDU/CSU 4395 B Kurt J. Rossmanith CDU/CSU . 4369 D Werner Schulz (Berlin) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Dr. Norbert Blüm, Bundesminister BMA 4371 D GRÜNEN 4396 C Rudolf Dreßler SPD 4375 B Jörg van Essen F.D.P. 4397 C Eva Bulling-Schröter PDS 4397 D Dr. Gisela Babel F.D.P 4378 A Marieluise Beck (Bremen) BÜNDNIS 90/ Tagesordnungspunkt 1 (Fortsetzung): DIE GRÜNEN 4379 C a) Erste Beratung des von der Bundesre- Hans-Joachim Fuchtel CDU/CSU . 4380 C gierung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Rudolf Dreßler SPD 4382A Gesetzes über die Feststellung des Annelie Buntenbach BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Bundeshaushaltsplans für das Haus- GRÜNEN 4384 A haltsjahr 1996 (Haushaltsgesetz 1996) (Drucksache 13/2000) Dr. Gisela Babel F.D.P 4386B Manfred Müller (Berlin) PDS 4388B b) Beratung der Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung Finanzplan des Bun- Ulrich Heinrich F D P. 4388 D des 1995 bis 1999 (Drucksache 13/2001) Ottmar Schreiner SPD 4390 A Dr. Günter Rexrodt, Bundesminister BMWi 4345 B Dr. Norbert Blüm CDU/CSU 4390 D - Ernst Schwanhold SPD . 4346D, 4360 B Gerda Hasselfeldt CDU/CSU 43928 Anke Fuchs (Köln) SPD 4349 A Dr. Jürgen Rüttgers, Bundesminister BMBF 4399B Dr. Hermann Otto Solms F.D.P. 4352A Doris Odendahl SPD 4401 D Birgit Homburger F D P. 4352 C Günter Rixe SPD 4401 D Ernst Hinsken CDU/CSU 4352B, 4370D, 4377 C Dr. -

Beyond Social Democracy in West Germany?

BEYOND SOCIAL DEMOCRACY IN WEST GERMANY? William Graf I The theme of transcending, bypassing, revising, reinvigorating or otherwise raising German Social Democracy to a higher level recurs throughout the party's century-and-a-quarter history. Figures such as Luxemburg, Hilferding, Liebknecht-as well as Lassalle, Kautsky and Bernstein-recall prolonged, intensive intra-party debates about the desirable relationship between the party and the capitalist state, the sources of its mass support, and the strategy and tactics best suited to accomplishing socialism. Although the post-1945 SPD has in many ways replicated these controversies surrounding the limits and prospects of Social Democracy, it has not reproduced the Left-Right dimension, the fundamental lines of political discourse that characterised the party before 1933 and indeed, in exile or underground during the Third Reich. The crucial difference between then and now is that during the Second Reich and Weimar Republic, any significant shift to the right on the part of the SPD leader- ship,' such as the parliamentary party's approval of war credits in 1914, its truck under Ebert with the reactionary forces, its periodic lapses into 'parliamentary opportunism' or the right rump's acceptance of Hitler's Enabling Law in 1933, would be countered and challenged at every step by the Left. The success of the USPD, the rise of the Spartacus move- ment, and the consistent increase in the KPD's mass following throughout the Weimar era were all concrete and determined reactions to deficiences or revisions in Social Democratic praxis. Since 1945, however, the dynamics of Social Democracy have changed considerably. -

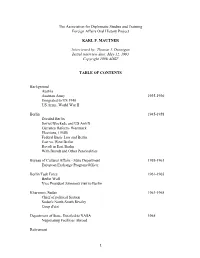

Mautner, Karl.Toc.Pdf

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project KARL F. MAUTNER Interviewed by: Thomas J. Dunnigan Initial interview date: May 12, 1993 opyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Austria Austrian Army 1 35-1 36 Emigrated to US 1 40 US Army, World War II Berlin 1 45-1 5, Divided Berlin Soviet Blockade and US Airlift .urrency Reform- Westmark Elections, 01 4,1 Federal Basic 2a3 and Berlin East vs. West Berlin Revolt in East Berlin With Brandt and Other Personalities Bureau of .ultural Affairs - State Department 1 5,-1 61 European E5change Program Officer Berlin Task Force 1 61-1 65 Berlin Wall 6ice President 7ohnson8s visit to Berlin 9hartoum, Sudan 1 63-1 65 .hief of political Section Sudan8s North-South Rivalry .oup d8etat Department of State, Detailed to NASA 1 65 Negotiating Facilities Abroad Retirement 1 General .omments of .areer INTERVIEW %: Karl, my first (uestion to you is, give me your background. I understand that you were born in Austria and that you were engaged in what I would call political work from your early days and that you were active in opposition to the Na,is. ould you tell us something about that- MAUTNER: Well, that is an oversimplification. I 3as born on the 1st of February 1 15 in 6ienna and 3orked there, 3ent to school there, 3as a very poor student, and joined the Austrian army in 1 35 for a year. In 1 36 I got a job as accountant in a printing firm. I certainly couldn8t call myself an active opposition participant after the Anschluss. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Plenarprotokoll 13/7 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 7. Sitzung Bonn, Freitag, den 25. November 1994 Inhalt: Abweichung von den Richtlinien für die Dr. Wolfgang Weng (Gerlingen) F.D.P. 290 A Fragestunde, für die Aktuellen Stunden Franziska Eichstädt-Bohlig BÜNDNIS 90/ sowie der Vereinbarung über die Befragung DIE GRÜNEN 292 C der Bundesregierung in der Sitzungswoche ab 12. Dezember 1994 259 A Klaus-Jürgen Warnick PDS 294 B Dr. Klaus Töpfer, Bundesminister BMBau 295 C Tagesordnungspunkt: Regierungserklärung des Bundeskanz- Ingrid Matthäus-Maier SPD 296 D lers Achim Großmann SPD 297 B (Fortsetzung der Aussprache) Dr.-Ing. Dietmar Kansy CDU/CSU 299 A Wolfgang Thierse SPD 259 B Elke Ferner SPD 300 A Dr. Jürgen Rüttgers, Bundesminister BMBWFT 263 A Dr. Dionys Jobst CDU/CSU 301 B Dr. Manuel Kiper BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜ Matthias Wissmann, Bundesminister BMV 303 D NEN 267 A Gila Altmann (Aurich) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE Dr. Wolfgang Gerhardt F.D.P. 268B GRÜNEN 305 C Hans-Werner Bertl SPD 270 B Manfred Grund CDU/CSU 306 C - Eckart Kuhlwein SPD 270 C Horst Friedrich F.D.P. 307 B 271 A Dr. Ludwig Elm PDS Dr. Dagmar Enkelmann PDS 309 D Dr. Peter Glotz SPD 272 D, 282 B Dr. Edmund Stoiber, Ministerpräsident Nächste Sitzung 310 D (Bayern) 276 B, 283 A Dr. Peter Glotz SPD 277 B Anlage 1 Dr. Helmut Lippelt BÜNDNIS 90/ Liste der entschuldigten Abgeordneten 311* A DIE GRÜNEN 277 D Horst Kubatschka SPD 278 A Anlage 2 279 C Jörg Tauss SPD Zu Protokoll gegebene Rede zu dem Tages- Elisabeth Altmann (Pommelsbrunn) BÜND ordnungspunkt: Regierungserklärung des NIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN 281 A Bundeskanzlers (Fortsetzung der Ausspra- Achim Großmann SPD 283 D che) Dr.-Ing. -

Yale University Library Digital Repository Contact Information

Yale University Library Digital Repository Collection Name: Henry A. Kissinger papers, part II Series Title: Series I. Early Career and Harvard University Box: 9 Folder: 21 Folder Title: Brandt, Willy Persistent URL: http://yul-fi-prd1.library.yale.internal/catalog/digcoll:554986 Repository: Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library Contact Information Phone: (203) 432-1735 Email: [email protected] Mail: Manuscripts and Archives Sterling Memorial Library Sterling Memorial Library P.O. Box 208240 New Haven, CT 06520 Your use of Yale University Library Digital Repository indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use http://guides.library.yale.edu/about/policies/copyright Find additional works at: http://yul-fi-prd1.library.yale.internal February 4, 1959 Mayor Willy Brandt Berlin ;ermany Dear Mayor Brandt: I returned to the United States a few days ago, and want to lose no time in thanking you for the extraordinary und interesting experience afforded to me in Berlin. It was of course a pleasure to have the chance to meet you. It seems to me that the courage and matter-of-factne$s of the Berliners should be an inspiration for the rest of the free world, and in this respect Berlin may well be the conscience of all of us. I want you to know that whatever I can do within my limited iowers here will U.) done. All good wishes and kind regards. ,Ancerely yours, iienryrt. Kissinger 2ZRI .4 xlsaldel Ibnala x1114; xamtneL abasme noyAM 11590 eydeb wel a ap.ts.ta be4inU ea pi benlidvi I ea lol pox anlAnadI n1 salt on pool od. -

Yale University Library Digital Repository Contact Information

Yale University Library Digital Repository Collection Name: Henry A. Kissinger papers, part II Series Title: Series I. Early Career and Harvard University Box: 9 Folder: 21 Folder Title: Brandt, Willy Persistent URL: http://yul-fi-uat1.library.yale.internal/catalog/digcoll:554986 Repository: Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library Contact Information Phone: (203) 432-1735 Email: [email protected] Mail: Manuscripts and Archives Sterling Memorial Library Sterling Memorial Library P.O. Box 208240 New Haven, CT 06520 Your use of Yale University Library Digital Repository indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use http://guides.library.yale.edu/about/policies/copyright Find additional works at: http://yul-fi-uat1.library.yale.internal February 4, 1959 Mayor Willy Brandt Berlin ;ermany Dear Mayor Brandt: I returned to the United States a few days ago, and want to lose no time in thanking you for the extraordinary und interesting experience afforded to me in Berlin. It was of course a pleasure to have the chance to meet you. It seems to me that the courage and matter-of-factne$s of the Berliners should be an inspiration for the rest of the free world, and in this respect Berlin may well be the conscience of all of us. I want you to know that whatever I can do within my limited iowers here will U.) done. All good wishes and kind regards. ,Ancerely yours, iienryrt. Kissinger 2ZRI .4 xlsaldel Ibnala x1114; xamtneL abasme noyAM 11590 eydeb wel a ap.ts.ta be4inU ea pi benlidvi I ea lol pox anlAnadI n1 salt on pool od. -

Kleine Anfrage

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 12/2569 12. Wahlperiode 06.05.92 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Wolf-Michael Catenhusen, Josef Vosen, Holger Bartsch, Edelgard Bulmahn, Ursula Burchardt, Lothar Fischer (Homburg), Ilse Janz, Horst Kubatschka, Siegmar Mosdorf, Dr. Helga Otto, Ursula Schmidt (Aachen), Bodo Seidenthal, Ulrike Mascher, Otto Schily, Hans Büchler (Hof), Hans Büttner (Ingolstadt), Dr. Peter Glotz, Susanne Kastner, Walter Kolbow, Uwe Lambinus, Robert Leidinger, Heide Mattischeck, Rudolf Müller (Schweinfurt), Dr. Martin Pfaff, Horst Schmidbauer (Nürnberg), Renate Schmidt (Nürnberg), Dr. Rudolf Schöfberger, Erika Simm, Dr. Sigrid Skarpelis-Sperk, Ludwig Stiegler, Uta Titze, Günter Verheugen, Dr. Axel Wernitz, Hermann Wimmer (Neuötting), Dr. Hans de With, Verena Wohlleben, Hanna Wolf, Renate Jäger, Dr. Peter Struck, Hans-Ulrich Klose und der Fraktion der SPD Wissenschaftliche Forschung an Neutronenquellen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und geplanter Forschungsreaktor München II In Garching ist der Bau eines neuen Forschungsreaktors der Technischen Universität München geplant, der als Neutronen- quelle für die physikalische Forschung an der Technischen Uni- versität München dienen soll. Sowohl innerhalb der Fachwissen- schaft als auch in der Region sind die Notwendigkeit und Aus- legung des geplanten Reaktors sowie die Risiken des Reaktorbe- triebs umstritten; am Physik-Department der Universität hat sich ein Arbeitskreis gebildet, der Alternativmodelle für eine risiko- ärmere Neutronenquelle vorgelegt hat. Wir fragen die Bundesregierung: -

Address Given by Willy Brandt to the Bundestag on the Building of the Berlin Wall (Bonn, 18 August 1961)

Address given by Willy Brandt to the Bundestag on the building of the Berlin Wall (Bonn, 18 August 1961) Caption: On 18 November 1961, Willy Brandt, Governing Mayor of Berlin, addresses the Bundestag and denounces the building of the Berlin Wall and the violation by the Soviet Union of the city’s four-power status. Source: Verhandlungen des deutschen Bundestages. 3. Wahlperiode. 167. Sitzung vom 18. August 1961. Stenographische Berichte. Hrsg. Deutscher Bundestag und Bundesrat. 1961, Nr. 49. Bonn. "Rede von Willy Brandt", p. 9773-9777. Copyright: (c) Translation CVCE.EU by UNI.LU All rights of reproduction, of public communication, of adaptation, of distribution or of dissemination via Internet, internal network or any other means are strictly reserved in all countries. Consult the legal notice and the terms and conditions of use regarding this site. URL: http://www.cvce.eu/obj/address_given_by_willy_brandt_to_the_bundestag_on_the _building_of_the_berlin_wall_bonn_18_august_1961-en-8c749afa-e8ac-4840-ac25- 3568a2d1a4d9.html Last updated: 05/07/2016 1/7 Address given by Willy Brandt to the Bundestag on the building of the Berlin Wall (Bonn, 18 August 1961) Brandt, Governing Mayor of Berlin (greeted with applause by the SPD): Mr Speaker, ladies and gentlemen, it is fairly rare for a component part of the Bundesrat to address this House. The fact that I appear before you today on behalf of the State of Berlin is a reflection of the extraordinary position in which we now find ourselves. It is not just Berlin that concerns us here, it is the cold menace which has settled over the other part of Germany and the Eastern sector of my city, as it once did over Hungary: you have all seen the pictures of the barbed wire, concrete posts and concrete walls, the tanks, the tank traps and the troops in full battle gear. -

Deutscheallgemeınezeitung

Общая Немецкая Газета DeutscheAllgemeıneZseit 1966eitung DIE DEUTSCH-RUSSISCHE WOCHENZEITUNG IN ZENTRALASIEN 07. bis 13. August 2009 Nr. 31/8391 Glühbirne Schritt für Schritt schaff t die Europäische Union die klassi- schen Glühbirnen ab – Desi- gner protestieren. 5 Hauptstadt Bild: http://idt-2009.de/ Berlin, die Weltmetropole der „Wenn die Deutschen sich nicht mehr für ihre Sprache engagieren, wird die Zahl der Deutschsprachigen weiter zurückgehen“, darin Gefühlsschwankungen – eine waren sich die Deutschlehrer aus 116 Ländern in Jena einig. Liebeserklärung von Autorin SPRACHPOLITIK Merle Hilbk. 9 DEUTSCHLEHRER FÜR MEHR DEUTSCH IM AUSLAND Sechs Tage lang diskutierten in der ersten Augustwoche rund 3.000 Deutschlehrer aus 116 Ländern über die Entwicklung der deutschen Sprache und die optimale Vermittlung von Deutsch als Fremdsprache. Die soll von deutschen Politikern im Ausland häufi ger gebraucht werden, fordern die Pädagogen. Der internationale Verband der Deutsch- Politiker und Wirtschaftsführer hätten dabei Sprachen. Rund 17 Millionen Ausländer lehrer hat deutsche Politiker aufgefordert, eine Vorbildfunktion – und oft sei das Deut- lernen Deutsch. Allerdings sei deren Zahl im Ausland öfter Deutsch zu sprechen. sche im Ausland die bessere Wahl: „Oft leiden in den vergangenen Jahren stark zurück- ЯЗЫК „Wenn die Deutschen bei offi ziellen Anläs- die Tiefe und die Klarheit der Gedanken, wenn gegangen. Немецкая республиканская sen im Ausland nicht ihre Muttersprache jemand versucht, die englische Sprache zu Besonders in Osteuropa, wo Deutsch benutzen, schaden sie der deutschen benutzen – ohne es zu können.“ lange stärker als Englisch gewesen sei, газета предлагает своим Sprache im Wettbewerb der Sprachen werde die deutsche Sprache zuneh- читателям возможность in einer globalen und mehrsprachigen Schwund in Osteuropa am größten mend verdrängt, sagte Hanuljaková. -

Die Stille Macht : Lobbyismus in Deutschland

HH_4c_Leif/Speth_14132-5•20 17.11.2003 14:00 SBK Seite 1 Thomas Leif · Rudolf Speth (Hrsg.) Lobbyisten scheuen das Licht der Öffentlichkeit, gewinnen in der Ber- liner Republik aber immer mehr an politischem Einfluss. Dennoch wird die „stille Macht“ Lobbyismus von der Wissenschaft, den Medien und der Öffentlichkeit selten in seinem gesamten Machtspektrum gewür- digt. In diesem Buch wird der Lobbyismus umfassend analysiert und DIE STILLE MACHT der ständig wachsende Einflussbereich von Wirtschaft auf politische Entscheidungen neu vermessen. Die politische und wissenschaftliche Analyse zur aktuellen Entwicklung der politischen Lobbyarbeit wird durch neue Studien und zahlreiche Fallbeispiele etwa der Pharma- lobby, Straßenbaulobby und Agrarlobby ergänzt. Wichtige Lobby- isten äußern sich zu ihrer Arbeit in Berlin. Auch der mächtige, aber DIE STILLE MACHT unkontrollierte Lobbyismus in Brüssel wird behandelt. Lobbyismus ist ein großes Tabuthema im parlamentarischen System der Bundesrepu- blik Deutschland. Erstmals werden unbekannte Einflusszonen aufge- deckt, die wichtigsten Akteure und ihre Machttechniken beschrieben. Die Macht der „Fünften Gewalt“ wird mit diesem Buch transparenter – ein Hintergrunddossier und gleichzeitig ein wichtiges Kapitel ver- schwiegener Sozialkunde. Dr. Thomas Leif ist Politikwissenschaftler und Chefreporter Fernsehen beim Südwestrundfunk, Landessender Mainz. Leif · Speth (Hrsg.) Dr. Rudolf Speth ist Politikwissenschaftler in Berlin. ISBN 3-531-14132-5 LOBBYISMUS IN DEUTSCHLAND www.westdeutscher-verlag.de 9 783531 -

Drucksache 12/5943 12

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 12/5943 12. Wahlperiode 20. 10. 93 Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Dr. Eberhard Brecht, Dr. Herta Däubler-Gmelin, Freimut Duve, Katrin Fuchs (Vert), Dr. Peter Glotz, Hans Koschnick, Markus Meckel, Volker Neumann (Bramsche), Dieter Schloten, Dr. Harmut Soell, Dr. Peter Struck, Margitta Terborg, Hans-Günther Toetemeyer, Karsten D. Voigt (Frankfurt), Gert Weisskirchen (Wiesloch), Uta Zapf, Dr. Christoph Zöpel, Hans-Ulrich Klose und der Fraktion der SPD Verlagerung von VN-Institutionen nach Bonn Wir fragen die Bundesregierung: 1. Hält die Bundesregierung an ihrer Absicht fest, als Kompensa- tion des Regierungs- und Parlamentsumzuges nach Berlin sich für die Etablierung von einer oder mehreren VN-Institutionen in Bonn einzusetzen? 2. An welche VN-Institution(en) hat sie dabei gedacht? 3. Wie bewertet die Bundesregierung die Installation einer inter- nationalen Ausbildungsstätte für VN-Personal in Bonn? 4. Wie groß sind noch die Chancen für einen Umzug des UNDP von New York nach Bonn? 5. Liegt ein Umzug des Weltbevölkerungsfonds UNFPA nach Bonn noch im Bereich des Möglichen? 6. Trifft es zu, daß ein VN-Informationszentrum UNIC — mög- lichst bis zum 1. Januar 1994 — in Bonn eingerichtet werden soll? 7. In welchem Umfang wird dadurch das Informationszentrum in Österreich abgebaut? 8. Inwieweit ist die österreichische Regierung an den Gesprä- chen über die Neuverteilung der Aufgaben von UNIC Wien beteiligt? 9. Wann ist mit dem Abschluß eines „host country agreement" zu rechnen? 10. Welches Gebäude ist für die Unterbringung des UNIC vorge- sehen? 11. Wird UNIC auch beim Regierungssitzwechsel von Bonn nach Berlin in Bonn verbleiben? 12. Wann ist mit einer Einigung mit den VN über die Finanzie- rung von UNIC zu rechnen? Drucksache 12/5943 Deutscher Bundestag — 12. -

Und Ostpolitik Der Ersten Großen Koalition in Der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (1966-1969)

Die Deutschland- und Ostpolitik der ersten Großen Koalition in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (1966-1969) Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Martin Winkels aus Erkelenz Bonn 2009 2 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät Der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission Vorsitzender: PD Dr. Volker Kronenberg Betreuer: Hon. Prof. Dr. Michael Schneider Gutacher: Prof. Dr. Tilman Mayer Weiteres prüfungsberechtigtes Mitglied: Hon. Prof. Dr. Gerd Langguth Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 11.11.2009 Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/diss_online elektonisch publiziert 3 Danksagung: Ich danke Herrn Professor Dr. Michael Schneider für die ausgezeichnete Betreuung dieser Arbeit und für die sehr konstruktiven Ratschläge und Anregungen im Ent- stehungsprozess. Ebenso danke ich Herrn Professor Dr. Tilman Mayer sehr dafür, dass er als Gutachter zur Verfügung gestanden hat. Mein Dank gilt auch den beiden anderen Mitgliedern der Prüfungskommission, Herrn PD Dr. Volker Kronenberg und Herrn Prof. Dr. Gerd Langguth. 4 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 7 1. Der Beginn der Außenpolitik der Bundesrepublik Deutschland ab 1949 und 23 die deutsche Frage 1.1. Die Deutschland- und Ostpolitik der Bundesregierung Adenauer zwischen 25 Westintegration und Kaltem Krieg (1949-1963) 1.2. Die Deutschland- und Ostpolitik unter Kanzler Erhard: Politik der 31 Bewegung (1963-1966) 1.3. Die deutschland- und ostpolitischen Gegenentwürfe der SPD im Span- 40 nungsfeld des Baus der Berliner Mauer: “Wandel durch Annäherung“ 2. Die Bildung der Großen Koalition: Ein Bündnis auf Zeit 50 2.1. Die unterschiedlichen Politiker-Biographien in der Großen Koalition im 62 Hinblick auf das Dritte Reich 2.2.