Images of the German Soldier (1985-2008)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. IRAN Christian Kracht, 1979 (2001) Popkultur Und Fundamentalismus I

3. IRAN Christian Kracht, 1979 (2001) Popkultur und Fundamentalismus I Den Titel seines Romans hat Christian Kracht gut gewählt. Das Jahr 1979 mar- kiert einen Umschwung in der Wahrnehmung des Orients durch den Westen. Zafer Şenocak, ein Grenzgänger zwischen den Kulturen, schreibt dazu: Bis 1979 – dem Jahr der islamischen Revolution im Iran – spielte der Islam auf der Weltbühne keine politisch herausragende Rolle. Er war bestenfalls tiefenpsycholo- gisch wirksam, als hemmender Faktor bei Modernisierungsbestrebungen in den muslimischen Ländern, im Zuge der Säkularisierung der Gesellschaft, beiseite ge- schoben von der westlich orientierten Elite dieser Länder. In Europa wurden die Gesichter des Islam zu Ornamenten einer sich nach Abwechslung und Fremde seh- nenden Zivilisation. Das Fremde im Islam war Identitätsspender, Kulminations- punkt von Distanzierung und Anziehung zugleich.1 Im Iran kündigten sich 1975 die ersten Unruhen an, als Schah Pahlavi das beste- hende Zweiparteiensystem auflöste und nur noch seine sogenannte Erneuerungs- partei zuließ.2 Oppositionsgruppen gab es aber nach wie vor, und die andauernde 01Zafer Şenocak, War Hitler Araber? IrreFührungen an den Rand Europas (Berlin: Babel, 1994). Die fiktionale Literatur, die sich aus iranischer Sicht mit der Revolution von 1979 und ihren Folgen beschäftigt, ist umfangreich. Zwei Titel seien genannt, weil sie von iranischen Autorinnen stam- men, die für ein westliches Publikum schreiben. Beide lehren inzwischen in den USA als Hoch- schulprofessorinnen: Azar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books (New York: Ran- dom House, 2003) und Fatemeh Keshavarz, Jasmine and Stars: Reading More than Lolita in Tehran (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007). Letzteres Buch versteht sich als Kritik an ersterem: Keshavarz wirft Nafisi eine Simplifizierung im Sinne des Opfer-Täter- Schemas und Reduktionismus vor. -

Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe

This page intentionally left blank Populist radical right parties in Europe As Europe enters a significant phase of re-integration of East and West, it faces an increasing problem with the rise of far-right political par- ties. Cas Mudde offers the first comprehensive and truly pan-European study of populist radical right parties in Europe. He focuses on the par- ties themselves, discussing them both as dependent and independent variables. Based upon a wealth of primary and secondary literature, this book offers critical and original insights into three major aspects of European populist radical right parties: concepts and classifications; themes and issues; and explanations for electoral failures and successes. It concludes with a discussion of the impact of radical right parties on European democracies, and vice versa, and offers suggestions for future research. cas mudde is Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science at the University of Antwerp. He is the author of The Ideology of the Extreme Right (2000) and the editor of Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe (2005). Populist radical right parties in Europe Cas Mudde University of Antwerp CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521850810 © Cas Mudde 2007 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: a Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power by Christopher J

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 15 The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: A Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power by Christopher J. Lamb, with Sarah Arkin and Sally Scudder Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for Complex Operations, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, Center for Technology and National Security Policy, and Conflict Records Research Center. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified com- batant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: President Bill Clinton addressing Croat-Muslim Federation Peace Agreement signing ceremony in the Old Executive Office Building, March 18, 1994 (William J. Clinton Presidential Library) The Bosnian Train and Equip Program The Bosnian Train and Equip Program: A Lesson in Interagency Integration of Hard and Soft Power By Christopher J. Lamb with Sarah Arkin and Sally Scudder Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 15 Series Editor: Nicholas Rostow National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. March 2014 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

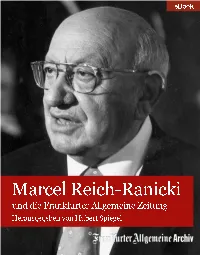

Marcel Reich-Ranicki

eBook Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel F.A.Z.-eBook 21 Frankfurter Allgemeine Archiv Projektleitung: Franz-Josef Gasterich Produktionssteuerung: Christine Pfeiffer-Piechotta Redaktion und Gestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher eBook-Produktion: rombach digitale manufaktur, Freiburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Rechteerwerb: [email protected] © 2013 F.A.Z. GmbH, Frankfurt am Main. Titelgestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher. Foto: F.A.Z.-Foto / Barbara Klemm ISBN: 978-3-89843-232-0 Inhalt Ein sehr großer Mann 7 Marcel Reich-Ranicki ist tot – Von Frank Schirrmacher ..... 8 Ein Leben – Von Claudius Seidl .................... 16 Trauerfeier für Reich-Ranicki – Von Hubert Spiegel ...... 20 Persönlichkeitsbildung 25 Ein Tag in meinem Leben – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 26 Wie ein kleiner Setzer in Polen über Adolf Hitler trium- phierte – Das Gespräch führten Stefan Aust und Frank Schirrmacher ................................. 38 Rede über das eigene Land – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki ... 55 Marcel Reich-Ranicki – Stellungnahme zu Vorwürfen ..... 82 »Mein Leben«: Das Buch und der Film 85 Die Quellen seiner Leidenschaft – Von Frank Schirrmacher � 86 Es gibt keinen Tag, an dem ich nicht ans Getto denke – Das Gespräch führten Michael Hanfeld und Felicitas von Lovenberg ................................... 95 Stille Hoffnung, nackte Angst: Marcel-Reich-Ranicki und die Gruppe 47 107 Alles war von Hass und Gunst verwirrt – Von Hubert Spiegel 108 Und alle, ausnahmslos alle respektierten diesen Mann – Von Marcel-Reich-Ranicki ....................... 112 Das Ende der Gruppe 47 – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 116 Große Projekte: die Frankfurter Anthologie und der »Kanon« 125 Der Kanonist – Das Gespräch führte Hubert Spiegel .... -

Plenarprotokoll 16/61 16

Schleswig-Holsteinischer Landtag Plenarprotokoll 16/61 16. Wahlperiode 07-06-07 Plenarprotokoll 61. Sitzung Donnerstag, 7. Juni 2007 Wirtschaftsbericht 2007................... 4368, Manfred Ritzek [CDU].................. 4383, Karl-Martin Hentschel [BÜND- Bericht der Landesregierung NIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN]............ 4388, Drucksache 16/1411 Beschluss: Überweisung an den Wirt- Dietrich Austermann, Minister für schaftsausschuss zur abschließen- Wissenschaft, Wirtschaft und den Beratung.................................. 4389, Verkehr..................................... 4368, 4384, Johannes Callsen [CDU]............... 4370, 4383, Erste Lesung des Entwurfs eines Bernd Schröder [SPD]................... 4372, 4388, Gesetzes zur Änderung des Denk- Dr. Heiner Garg [FDP].................. 4375, 4386, malschutzgesetzes............................. 4389, Detlef Matthiessen [BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN]................... 4377, Gesetzentwurf der Fraktion BÜND- Lars Harms [SSW]......................... 4380, 4386, NIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Jürgen Feddersen [CDU]............... 4382, Drucksache 16/1380 (neu) 4366 Schleswig-Holsteinischer Landtag (16. WP) - 61. Sitzung - Donnerstag, 7. Juni 2007 Karl-Martin Hentschel [BÜND- Günter Neugebauer [SPD], Be- NIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN]............ 4389, richterstatter.............................. 4415, Wilfried Wengler [CDU]............... 4391, Tobias Koch [CDU]....................... 4416, Ulrike Rodust [SPD]...................... 4392, Birgit Herdejürgen [SPD].............. 4417, Dr. Ekkehard Klug [FDP].............. 4393, Wolfgang -

American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler's Death

American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler’s Death Undergraduate Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in History in the Undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Kelsey Mullen The Ohio State University November 2014 Project Advisor: Professor Alice Conklin, Department of History Project Mentor: Doctoral Candidate Sarah K. Douglas, Department of History American Intelligence and the Question of Hitler’s Death 2 Introduction The fall of Berlin marked the end of the European theatre of the Second World War. The Red Army ravaged the city and laid much of it to waste in the early days of May 1945. A large portion of Hitler’s inner circle, including the Führer himself, had been holed up in the Führerbunker underneath the old Reich Chancellery garden since January of 1945. Many top Nazi Party officials fled or attempted to flee the city ruins in the final moments before their destruction at the Russians’ hands. When the dust settled, the German army’s capitulation was complete. There were many unanswered questions for the Allies of World War II following the Nazi surrender. Invading Russian troops, despite recovering Hitler’s body, failed to disclose this fact to their Allies when the battle ended. In September of 1945, Dick White, the head of counter intelligence in the British zone of occupation, assigned a young scholar named Hugh Trevor- Roper to conduct an investigation into Hitler’s last days in order to refute the idea the Russians promoted and perpetuated that the Führer had escaped.1 Major Trevor-Roper began his investigation on September 18, 1945 and presented his conclusions to the international press on November 1, 1945. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Plenarprotokoll 15/56

Plenarprotokoll 15/56 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 56. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 3. Juli 2003 Inhalt: Begrüßung des Marschall des Sejm der Repu- rung als Brücke in die Steuerehr- blik Polen, Herrn Marek Borowski . 4621 C lichkeit (Drucksache 15/470) . 4583 A Begrüßung des Mitgliedes der Europäischen Kommission, Herrn Günter Verheugen . 4621 D in Verbindung mit Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Michael Kauch . 4581 A Benennung des Abgeordneten Rainder Tagesordnungspunkt 19: Steenblock als stellvertretendes Mitglied im a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Michael Programmbeirat für die Sonderpostwert- Meister, Friedrich Merz, weiterer Ab- zeichen . 4581 B geordneter und der Fraktion der CDU/ Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 4582 D CSU: Steuern: Niedriger – Einfa- cher – Gerechter Erweiterung der Tagesordnung . 4581 B (Drucksache 15/1231) . 4583 A b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Hermann Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: Otto Solms, Dr. Andreas Pinkwart, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion Abgabe einer Erklärung durch den Bun- der FDP: Steuersenkung vorziehen deskanzler: Deutschland bewegt sich – (Drucksache 15/1221) . 4583 B mehr Dynamik für Wachstum und Be- schäftigung 4583 A Gerhard Schröder, Bundeskanzler . 4583 C Dr. Angela Merkel CDU/CSU . 4587 D in Verbindung mit Franz Müntefering SPD . 4592 D Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4596 D Tagesordnungspunkt 7: Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen DIE GRÜNEN . 4600 A der SPD und des BÜNDNISSES 90/ DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Ent- Dr. Guido Westerwelle FDP . 4603 B wurfs eines Gesetzes zur Förderung Krista Sager BÜNDNIS 90/ der Steuerehrlichkeit DIE GRÜNEN . 4603 C (Drucksache 15/1309) . 4583 A Michael Glos CDU/CSU . 4603 D b) Erste Beratung des von den Abgeord- neten Dr. Hermann Otto Solms, Hubertus Heil SPD . -

Protokoll Der 64. Sitzung

Protokoll-Nr. 18/64 18. Wahlperiode Innenausschuss Wortprotokoll der 64. Sitzung Innenausschuss Berlin, den 14. Dezember 2015, 14:00 Uhr 10117 Berlin, Adele-Schreiber-Krieger-Straße 1 Marie-Elisabeth-Lüders-Haus 3.101 (Anhörungssaal) Vorsitz: Ansgar Heveling, MdB Öffentliche Anhörung a) Gesetzentwurf der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und Federführend: SPD Innenausschuss Entwurf eines ... Gesetzes zur Änderung des Mitberatend: Parteiengesetzes Ausschuss für Recht und Verbraucherschutz BT-Drucksache 18/6879 Berichterstatter/in: Abg. Helmut Brandt [CDU/CSU] Abg. Gabriele Fograscher [SPD] Abg. Frank Tempel [DIE LINKE.] Abg. Britta Haßelmann [BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN] b) Antrag der Abgeordneten Halina Wawzyniak, Jan Federführend: Innenausschuss Korte, Matthias W. Birkwald, weiterer Mitberatend: Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. Ausschuss für Recht und Verbraucherschutz Parteispenden von Unternehmen und Berichterstatter/in: Wirtschaftsverbänden verbieten, Parteispenden Abg. Helmut Brandt [CDU/CSU] Abg. Gabriele Fograscher [SPD] natürlicher Personen begrenzen Abg. Britta Haßelmann [BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN] Abg. Frank Tempel [DIE LINKE.] BT-Drucksache 18/301 18. Wahlperiode Seite 1 von 84 Innenausschuss Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite I. Anwesenheitslisten 3 II. Sachverständigenliste 10 III. Sprechregister der Sachverständigen und Abgeordneten 11 IV. Wortprotokoll der Öffentlichen Anhörung 12 V. Anlagen 37 Anlage A Stellungnahmen der Sachverständigen zur Öffentlichen Anhörung Prof. Dr. Martin Morlok 18(4)462 A Prof. Dr. Bernd Grzeszick 18(4)462 B Dr. Michael Koß 18(4)462 C Dr. Christian Deckwirth 18(4)462 D Prof. Dr. Foroud Shirvani 18(4)462 E 18. Wahlperiode Protokoll der 64. Sitzung Seite 2 von 84 vom 14. Dezember 2015 Innenausschuss 18. Wahlperiode Protokoll der 64. Sitzung Seite 3 von 84 vom 14. Dezember 2015 Innenausschuss 18. -

KNIGHT Wake Forest University

Forbidden Fruit Civil Savagery in Christian Kracht’s Imperium “Ich war ein guter Gefangener. Ich habe nie Menschenfleisch gegessen.” I was a good prisoner. I never ate human flesh. These final words of Christian Kracht’s second novel, 1979, represent the last shred of dignity retained by the German protagonist, who is starving to death in a Chinese prison camp in the title year. Over and over, Kracht shows us a snapshot of what happens to the over-civilized individual when civilization breaks down. Faserland’s nameless narrator stands at the water’s edge, preparing to drown rather than live with his guilt and frustration; even the portrait of Kracht on the cover of his edited volume Mesopotamia depicts Kracht himself in a darkened wilderness, wearing a polo shirt and carrying an AK-47. In each of these moments, raw nature inspires the human capacity for violence and self-destruction as a sort of ironic antidote to the decadence and vacuity of a society in decline. Kracht’s latest novel, Imperium, further explicates this moment of annihilation. The story follows the fin-de-siècle adventures of real-life eccentric August Engelhardt, a Nuremberger who wears his hair long, promotes nudism, and sets off for the German colony of New Guinea in hopes of founding a cult of sun-worshippers and cocovores (i.e., people who subsist primarily on coconuts). Engelhardt establishes a coconut plantation near the small town of Herbertshöhe, where he attempts to practice his beliefs in the company of a series of companions of varying worth and, finally, in complete solitude. -

German Studies Association Newsletter ______

______________________________________________________________________________ German Studies Association Newsletter __________________________________________________________________ Volume XLIV Number 1 Spring 2019 German Studies Association Newsletter Volume XLIV Number 1 Spring 2019 __________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Letter from the President ............................................................................................................... 2 Letter from the Executive Director ................................................................................................. 5 Conference Details .......................................................................................................................... 8 Conference Highlights ..................................................................................................................... 9 Election Results Announced ......................................................................................................... 14 A List of Dissertations in German Studies, 2017-19 ..................................................................... 16 Letter from the President Dear members and friends of the GSA, To many of us, “the GSA” refers principally to a conference that convenes annually in late September or early October in one city or another, and which provides opportunities to share ongoing work, to network with old and new friends and colleagues. And it is all of that, for sure: a forum for