Stunde Null: the End and the Beginning Fifty Years Ago." Their Contributions Are Presented in This Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D'antonio, Michael Senior Thesis.Pdf

Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Degree in History with Distinction Spring 2016 © 2016 Michael D’Antonio All Rights Reserved Before the Storm German Big Business and the Rise of the NSDAP by Michael D’Antonio Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. James Brophy Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. David Shearer Committee member from the Department of History Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Dr. Barbara Settles Committee member from the Board of Senior Thesis Readers Approved: ____________________________________________________________ Michael Arnold, Ph.D. Director, University Honors Program ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This senior thesis would not have been possible without the assistance of Dr. James Brophy of the University of Delaware history department. His guidance in research, focused critique, and continued encouragement were instrumental in the project’s formation and completion. The University of Delaware Office of Undergraduate Research also deserves a special thanks, for its continued support of both this work and the work of countless other students. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................. -

The German-American Bund: Fifth Column Or

-41 THE GERMAN-AMERICAN BUND: FIFTH COLUMN OR DEUTSCHTUM? THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By James E. Geels, B. A. Denton, Texas August, 1975 Geels, James E., The German-American Bund: Fifth Column or Deutschtum? Master of Arts (History), August, 1975, 183 pp., bibliography, 140 titles. Although the German-American Bund received extensive press coverage during its existence and monographs of American politics in the 1930's refer to the Bund's activities, there has been no thorough examination of the charge that the Bund was a fifth column organization responsible to German authorities. This six-chapter study traces the Bund's history with an emphasis on determining the motivation of Bundists and the nature of the relationship between the Bund and the Third Reich. The conclusions are twofold. First, the Third Reich repeatedly discouraged the Bundists and attempted to dissociate itself from the Bund. Second, the Bund's commitment to Deutschtum through its endeavors to assist the German nation and the Third Reich contributed to American hatred of National Socialism. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION... ....... 1 II. DEUTSCHTUM.. ......... 14 III. ORIGIN AND IMAGE OF THE GERMAN- ... .50 AMERICAN BUND............ IV. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE BUND AND THE THIRD REICH....... 82 V. INVESTIGATION OF THE BUND. 121 VI. CONCLUSION.. ......... 161 APPENDIX....... .............. ..... 170 BIBLIOGRAPHY......... ........... -

German Hegemony and the Socialist International's Place in Interwar

02_EHQ 31/1 articles 30/11/00 1:53 pm Page 101 William Lee Blackwood German Hegemony and the Socialist International’s Place in Interwar European Diplomacy When the guns fell silent on the western front in November 1918, socialism was about to become a governing force throughout Europe. Just six months later, a Czech socialist could marvel at the convocation of an international socialist conference on post- war reconstruction in a Swiss spa, where, across the lake, stood buildings occupied by now-exiled members of the deposed Habsburg ruling class. In May 1923, as Europe’s socialist parties met in Hamburg, Germany, finally to put an end to the war-induced fracturing within their ranks by launching a new organization, the Labour and Socialist International (LSI), the German Communist Party’s main daily published a pull-out flier for posting on factory walls. Bearing the sarcastic title the International of Ministers, it presented to workers a list of forty-one socialists and the national offices held by them in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Poland, France, Sweden, and Denmark. Commenting on the activities of the LSI, in Paris a Russian Menshevik émigré turned prominent left-wing pundit scoffed at the new International’s executive body, which he sarcastically dubbed ‘the International Socialist Cabinet’, since ‘all of its members were ministers, ex-ministers, or prospec- tive ministers of State’.1 Whether one accepted or rejected its new status, socialism’s virtually overnight transformation from an outsider to a consummate insider at the end of Europe’s first total war provided the most striking measure of the quantum leap into what can aptly be described as Europe’s ‘social democratic moment’.2 Moreover, unlike the period after Europe’s second total war, when many of socialism’s basic postulates became permanently embedded in the post-1945 social-welfare-state con- European History Quarterly Copyright © 2001 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Whose Brain Drain? Immigrant Scholars and American Views of Germany

Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program Series Volume 9 WHOSE BRAIN DRAI N? IMMIGRANT SCHOLARS AND AMERICAN VIEWS OF GERMANY Edited by Peter Uwe Hohendahl Cornell University American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program Series Volume 9 WHOSE BRAIN DRAIN? IMMIGRANT SCHOLARS AND AMERICAN VIEWS OF GERMANY Edited by Peter Uwe Hohendahl Cornell University The American Institute for Contemporary German Studies (AICGS) is a center for advanced research, study and discussion on the politics, culture and society of the Federal Republic of Germany. Established in 1983 and affiliated with The Johns Hopkins University but governed by its own Board of Trustees, AICGS is a privately incorporated institute dedicated to independent, critical and comprehensive analysis and assessment of current German issues. Its goals are to help develop a new generation of American scholars with a thorough understanding of contemporary Germany, deepen American knowledge and understanding of current German developments, contribute to American policy analysis of problems relating to Germany, and promote interdisciplinary and comparative research on Germany. Executive Director: Jackson Janes Board of Trustees, Cochair: Fred H. Langhammer Board of Trustees, Cochair: Dr. Eugene A. Sekulow The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©2001 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-55-5 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. -

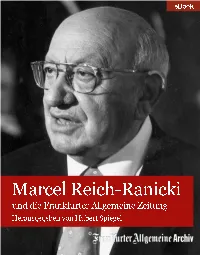

Marcel Reich-Ranicki

eBook Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel Marcel Reich-Ranicki und die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung Herausgegeben von Hubert Spiegel F.A.Z.-eBook 21 Frankfurter Allgemeine Archiv Projektleitung: Franz-Josef Gasterich Produktionssteuerung: Christine Pfeiffer-Piechotta Redaktion und Gestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher eBook-Produktion: rombach digitale manufaktur, Freiburg Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Rechteerwerb: [email protected] © 2013 F.A.Z. GmbH, Frankfurt am Main. Titelgestaltung: Hans Peter Trötscher. Foto: F.A.Z.-Foto / Barbara Klemm ISBN: 978-3-89843-232-0 Inhalt Ein sehr großer Mann 7 Marcel Reich-Ranicki ist tot – Von Frank Schirrmacher ..... 8 Ein Leben – Von Claudius Seidl .................... 16 Trauerfeier für Reich-Ranicki – Von Hubert Spiegel ...... 20 Persönlichkeitsbildung 25 Ein Tag in meinem Leben – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 26 Wie ein kleiner Setzer in Polen über Adolf Hitler trium- phierte – Das Gespräch führten Stefan Aust und Frank Schirrmacher ................................. 38 Rede über das eigene Land – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki ... 55 Marcel Reich-Ranicki – Stellungnahme zu Vorwürfen ..... 82 »Mein Leben«: Das Buch und der Film 85 Die Quellen seiner Leidenschaft – Von Frank Schirrmacher � 86 Es gibt keinen Tag, an dem ich nicht ans Getto denke – Das Gespräch führten Michael Hanfeld und Felicitas von Lovenberg ................................... 95 Stille Hoffnung, nackte Angst: Marcel-Reich-Ranicki und die Gruppe 47 107 Alles war von Hass und Gunst verwirrt – Von Hubert Spiegel 108 Und alle, ausnahmslos alle respektierten diesen Mann – Von Marcel-Reich-Ranicki ....................... 112 Das Ende der Gruppe 47 – Von Marcel Reich-Ranicki .... 116 Große Projekte: die Frankfurter Anthologie und der »Kanon« 125 Der Kanonist – Das Gespräch führte Hubert Spiegel .... -

Hermann Göring« Im Salzgittergebiet

Mobilisierung und Migration. Die Reichswerke »Hermann Göring« im Salzgittergebiet VON LARS AMENDA ›Mobilisierung‹ war für Nationalsozialisten keine leere Worthülse, sondern charakterisierte das politische Programm und seine staatliche Umsetzung nach 1933.1 Der militärisch konnotierte Begriff verschmolz die emotionale Hingabe und die kühle Sachlichkeit, mit der die maßgeblichen Protagonis- ten und Planer die nationalsozialistischen Ziele ausgaben und später in die Praxis umzusetzen versuchten. Unmittelbar nach der Machtübernahme waren sich Adolf Hitler und die NS-Führungsriege darüber im Klaren, dass die deutsche Wirtschaft auf einen kommenden Krieg ausgerichtet und umgestellt werden sollte.2 Die nationalsozialistischen Arbeitsbeschaffungsmaßnahmen3 der Jahre 1933 und 1934 kennzeichneten die wahren Ziele des NS-Regimes deutlich weniger als der Vierjahresplan von 1936, für den Hermann Göring als Bevollmächtigter verantwortlich war.4 Am Beispiel der Reichswerke »Hermann Göring« im Salzgittergebiet wird im Folgenden das Wechselverhältnis von staatlicher Mobilisierung und menschlicher Mobilität untersucht und nach Grundlinien und Grenzen natio- nalsozialistischer ›Migrationspolitik‹ gefragt. Die Einwanderung ausländi- scher Arbeitskräfte in das nationalsozialistische Deutschland war dabei alles andere erwünscht, deklarierte das NSDAP-Parteiprogramm 1920 doch bereits, dass die Zuwanderung von Ausländern konsequent beschränkt und beschnit- ten werden solle.5 Dennoch stiegen die Zahlen ausländischer Arbeitskräfte mit dem Absinken der Arbeitslosenquote -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Clandestine Agent the Real Agnes Smedley

CEclanksteindestine Agent Review Essay Clandestine Agent The Real Agnes Smedley ✣ Arthur M. Eckstein Ruth Price, The Lives of Agnes Smedley. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. x ϩ 483 pp. Agnes Smedley (1892–1950) was one of several American radical women in the 1920s and 1930s who made a signiªcant impact on American (and in- deed world) culture and politics. Other ªgures on the list include Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood (she was British by birth), and Emma Goldman, the socialist activist and writer. Agnes Smedley was an assis- tant and friend of Margaret Sanger and a friend of Emma Goldman. Like Goldman, Smedley was a fervent advocate of a socialist society to replace capi- talism, and she worked hard to bring it about. Smedley was also an ardent supporter of the destruction of European (and American) empires in what we now call the Third World. She was ªrst drawn to the Indian independence movement against Britain, but her ªnal and overwhelming love was China, where she was an extraordinarily effective propagandist for the Communist revolution led by Mao Zedong. In addition, Smedley was a cultural radical: She cut her hair short, wore men’s clothing, fervently advocated and practiced “free love,” and—unusual for a woman of that time—had an independent career as a journalist and for- eign correspondent and was the author of best-selling books (an autobio- graphical novel and several books on the Maoist revolution in China). Finally, Smedley became a hero in some circles as a supposed victim of “Cold War McCarthyism.” In the late 1940s she was accused both by General Douglas MacArthur and by the House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) of having been a spy for the Soviet Union and of having been one of the people who (through her propaganda against the Chinese Nationalist gov- Journal of Cold War Studies Vol. -

Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 49 Number 2 Article 2 4-1-1974 Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946 Jake W. Spidle Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Spidle, Jake W.. "Axis Invasion of the American West: POWS in New Mexico, 1942-1946." New Mexico Historical Review 49, 2 (2021). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol49/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. 93 AXIS INVASION OF THE AMERICAN WEST: POWS IN NEW MEXICO, 1942-1946 JAKE W. SPIDLE ON A FLAT, virtually treeless stretch of New Mexico prame, fourteen miles southeast of the town of Roswell, the wind now kicks up dust devils where Rommel's Afrikakorps once marched. A little over a mile from the Orchard Park siding of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific railroad line, down a dusty, still unpaved road, the concrete foundations of the Roswell Prisoner of War Internment Camp are still visible. They are all that are left from what was "home" for thousands of German soldiers during the period 1942-1946. Near Lordsburg there are similar ruins of another camp which at various times during the years 1942-1945 held Japanese-American internees from the Pacific Coast and both Italian and German prisoners of war. -

Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei Gegenüber Dem

1 2 3 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei gegenüber dem 4 Nationalsozialismus und dem Reichskonkordat 1930–1933: 5 Motivationsstrukturen und Situationszwänge* 6 7 Von Winfried Becker 8 9 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei wurde am 13. Dezember 1870 von ca. 50 Man- 10 datsträgern des preußischen Abgeordnetenhauses gegründet. Ihre Reichstagsfrak- 11 tion konstituierte sich am 21. März 1871 beim Zusammentritt des ersten deut- 12 schen Reichstags. 1886 vereinigte sie sich mit ihrem bayerischen Flügel, der 1868 13 eigenständig als Verein der bayerischen Patrioten entstanden war. Am Ende des 14 Ersten Weltkriegs, am 12. November 1918, verselbständigte sich das Bayerische 15 Zentrum zur Bayerischen Volkspartei. Das Zentrum verfiel am 5. Juli 1933 der 16 Selbstauflösung im Zuge der Beseitigung aller deutschen Parteien (außer der 17 NSDAP), ebenso am 3. Juli die Bayerische Volkspartei. Ihr war auch durch die 18 Gleichschaltung Bayerns und der Länder der Boden entzogen worden.1 19 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei der Weimarer Republik war weder mit der 20 katholischen Kirche dieser Zeit noch mit dem Gesamtphänomen des Katho- 21 lizismus identisch. 1924 wählten nach Johannes Schauff 56 Prozent aller Ka- 22 tholiken (Männer und Frauen) und 69 Prozent der bekenntnistreuen Katholiken 23 in Deutschland, von Norden nach Süden abnehmend, das Zentrum bzw. die 24 Bayerische Volkspartei. Beide Parteien waren ziemlich beständig in einem 25 Wählerreservoir praktizierender Angehöriger der katholischen Konfession an- 26 gesiedelt, das durch das 1919 eingeführte Frauenstimmrecht zugenommen hat- 27 te, aber durch die Abwanderung vor allem der männlichen Jugend von schlei- 28 chender Auszehrung bedroht war. Politisch und parlamentarisch repräsentierte 29 die Partei eine relativ geschlossene katholische »Volksminderheit«.2 Ihre re- 30 gionalen Schwerpunkte lagen in Bayern, Südbaden, Rheinland, Westfalen, 31 32 * Erweiterte und überarbeitete Fassung eines Vortrags auf dem Symposion »Die Christ- 33 lichsozialen in den österreichischen Ländern 1918–1933/34« in Graz am 4. -

Georg G. Iggers §

ᐖಮጱࡒ ጱి ¡ ¢ £¤ ¢ ¥ ¦ ¨ © Georg G. Iggers § ¦ !" # $ %%& Weinmann Lecture § ;< ,-./ 0 $ , $3 4 3 4 9 : = >? @A * + * 1 2+ % 8 B '( ) () 5 67 CD V D E GHI M N $OEP R 0ST SU Y Z % JKL WX *B F ) 7 Q D [ $ ,\ ^ _ ab c e $gh ijkl Ym Z [ $n o 12+ ] B 7` d f 7 D ,s ${ | } ~ s p + X y z 5 d 7 dr 7tu v w x Q 11 q ;< D p $ s $ -s L %% L ( 5 5 6 1945 D ;< < ¥ } $ i $¡ ¢ £ 8 X % ' 5 ¦ d¤ § ¨ 7 Q ;< , > $ ® $ S±²Y e 0 «0 ¬ & ´ * + % ¯ ° 1 2 ©ª) ª f ³ w x 7 Q ;< µ {¶,· ¸s ¹ µ { $[º P P$p $¾ »p¼ X ´ L ½ ¨ ³ 1 Q D ¿ p Ä!" $Å Æ R ¬ ÊË É STS 1 2 ÀÁ ª È ÂÃu 7 Ç d Q Í ;< ¬Ì i$ 0 ¬ $¾¿ ÏÐ $ > Pp $ p L Ñ Î ª 7 Ç d Q µ {¶,Õ ØÙ Ê > Ú oÚ É R ÒÓÔ 12 ´ X X12Ö × ª ' È dr Q ;< ÛT Ó [ Y X + ( Q CD D ;< s p ? > { ÞSÓÏ ßà áâ % 1 2 & ã1 2ä X ÁÜ Ý 7 ³ w x D å ç S è s P Ië P ./0s îâ P X % 2 ° í y æ ÁÜ é ê ì ï 7 Q $ðÆ P gh ô i P I ë S á ¸õs Pö ë í& ò % ° ã ° 1 2 1 2 ó ì § ñ ¨ 7 Q ÷ Pøùpõ ú s Pö ë÷û øùp îâ - ý | c ú¸õ µ 1 2 ÖüJ 1 2ÿ þ t Q £ ¤ £§¨ £ s $Ù ô ùõ¡ J© 1 2 ¥ ¦ Ü Q 20 ¢ 20 p Ó $ ¦ 1 2 81 2 1 2+ § ¨ ¨ Q Jüdische Lehrhaus § ¦ -!" ¦ $ ¦ s Ö Ö J# Ö ¨ ¨ Q § § Jüdische Verlag § Philo Verlag Schocken Verlag 1933 D D % )* ô i ç Y Z - ® % 1 2 &'( & +, ° 1 2Ö × .